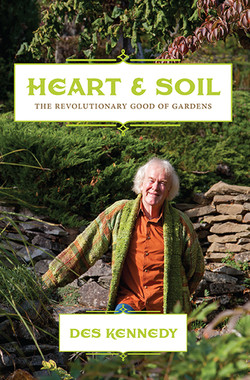

Читать книгу Heart & Soil - Des Kennedy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGreen-Fingered Grannies and Ancient Gentlemen

The first small hints that spring is icumen in—the sweet scent of sarcococca by the doorway on a sunny afternoon, the thrilling shoots of stinging nettles in a sheltered corner—reawaken a great illusion: that springtime is the childhood of the year, the beginning of new life, a time of freshness, beauty and innocence, leading to long seasons of growth and fruitfulness. Late autumn and winter are seen as the seasons of age, spring the time for the lusty young blood of youth.

Poets have been dining out on this metaphor for centuries and, poets being what they are, insisting that youth is not only the first of life’s seasons, but also the best. “That age is best which is the first,” wrote Elizabethan Robert Herrick, “when youth and blood are warmer.” Victorian Edward Fitzgerald was still plucking the same lyre three centuries later: “Yet Ah, that Spring should vanish with the Rose! / That Youth’s sweet-scented manuscript should close!”

Having already received a gold card from the government, and thereby taken a considerable leap into the wisdom of age, I’m more inclined than ever to take issue with this infernal glorification of vernal youth. It’s certainly true that, like the garden in springtime, youth’s a lot of bloody muddling around in the muck. Sure, it involves great hot rushes of enthusiasm, considerable dreaming of impossible dreams and much swooning over objects of affection that will soon enough prove themselves more appealing in imagination than in reality. Youth’s sweet-scented manuscript, much like a gullible gardener’s order form for springtime seeds, all too often turns out to be a work of romantic fantasy.

Here’s the bold counter-stroke I’m prepared to propose: that spring is at its pith the great season of our elders. Any thoughtful sounding of spring’s resonances confirms that this is so. Even the most poetical gardener would hesitate to characterize the first growth of spring as new birth. The emergence of annuals planted from seed (indoors and often far earlier than required) does have this quality of the entirely new, but it pales in significance compared with the real growth happening at this earliest time of the year, the wonderful earth-surge trembling all around us. This isn’t birth, it’s rebirth, a stirring of ancient forces. The exotic spathes of swamp lanterns, the primeval flowering stalks of petasites, the jubilant nubs of crocus and snowdrops emerging from frosty ground—these are not birthings, nor the noisy exuberances of youth; these are the reawakening of old friends we have known forever.

Our culture at large, devoted as it is to the frenzied movement of merchandise, is unabashed in its obsession with the new and the hip and the hot and the flash. Dizzy crowds mill for hours through shopping malls, seeking articles of transformation, greying oldsters search for the fountain of youth. The glitter of illusions and delusions may be tastefully gift-wrapped for any occasion. Nature knows better; the garden knows better. In its depths, the old is new again and spring is its season of renewal.

Gardening is above all else an experiential undertaking. The longer you stay at it, the more you come to appreciate its complexities and depths. The true gardening community, unlike market demographers in cheap suits, holds in highest regard its elders, those who have had their hands in earth for half a century or more. I’m thinking of many remarkable sexagenarians and octogenarians whose gardens I’ve been privileged to visit. Of all our green-fingered grannies and aunties and mums, and of some ancient gentlemen too.

I don’t know quite why, but so many of them are tiny wee people with impish grins and sprightly energy. Their eyes seem to twinkle with mischief; the lines on their faces are the outlines of smiles. Their minds are sharp as new secateurs, their enthusiasm high and their spirits still willing even though the flesh may have weakened just a titch over time. Make no mistake: these are the children of Pan, the true sprites of spring.

Were I to select a plant to symbolize them, I should choose the winter aconite, Eranthis. These are among the very first flowers to show themselves at our place, earlier than snowdrops or snow crocus. Their bloom is a miniature golden orb held above the frigid soil on a Tudor-style ruff of ornately cut leaves. They grow from small tuberous roots planted shallow. A day or two of sunny weather will coax them into bloom and if the weather turns filthy again, they simply huddle within their enfolding leaves and wait for conditions to improve. They are survivors, tiny but tough as nails and, once established, spread persistently through favourable places in the garden. Their hardy perseverance, their cheerful radiance during times too challenging for most other spring bloomers—these are the very qualities we admire in our gardening veterans.

So, by all means, let’s join the poets in celebrating the warm blood of youth, but do so at the appropriate moment, as during the softer charms of May. For the true spirit of spring, the abiding strength of resurgent earth, I say let’s look to the more tenacious beauty of our elders.