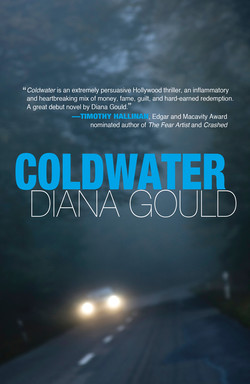

Читать книгу Coldwater - Diana Gould - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеI’ve spent so much of my life afraid of the wrong thing. Lying awake, fretting what-ifs. My boyfriend will leave me. This headache is cancer. We’re in production and on location: What if it rains and we can’t make the day? As if fear were a protective shield that could ward off disaster. I’m pregnant. The show I’m working on will be cancelled. Preemptive worrying: what you dread won’t happen if only you agonize first. The pilot won’t sell. I’m HIV-positive. Why didn’t I insist on a condom? Then, when it doesn’t rain, you aren’t fired, positive, or pregnant, it’s a plus, not a neutral; you’re not only free, you’ve accomplished something.

What you fear rarely happens, so worry and be safe.

There’s only one thing wrong with that plan.

Sometimes what happens is worse.

That night, what I was afraid of was being late on a script. We’d been prepping off an outline for two days; the messenger was coming at six a.m. to bring the script to the director. I’d run out of coke. I couldn’t write without it.

I was a writer-producer, show-runner of a TV show I’d created, two months past my thirty-first birthday. Five years before, I’d been a reporter on the metro desk of a newspaper in San Diego when I’d met Jonathan Weissman at one of those “How to Break into Television” panels. I’d had an idea for a series; he liked the idea, and he liked me. He helped me develop it, and in the process, we fell in love. I moved in with him and his young daughter, Julia. Eventually, miraculously, we sold our show, Murder Will Out, about a crime reporter turned private eye named Jinx Magruder.

Now two thirds into our second season, I was having trouble with a script that was already late. I’d called my dealer, Zeke, and asked him to come over, but his car was in the shop, and he said I’d have to go to him.

Jonathan was in New York for the upfronts—the week in May when the networks chose their fall season. It was the nanny’s night off. I was alone in the house with Julia.

I stood in the doorway to Julia’s room. Julia was not yet thirteen. Sleeping, she still looked like a child; although the fragile beauty of her movie-star mother was emerging as she grew to womanhood. Her hair was splayed over her pillow, an old and tattered Piglet doll nearby, not held, but there, a talisman of the childhood she was leaving behind, sidekick for the journey to adolescence ahead.

What to do? Wake her and take her with me? Leave her in the car while I run in, score, and leave? Or leave her alone and asleep.

What would I say? “I need to get drugs. I can’t write without them. Just wait in the car while I go in and get them.”

Julia was old enough to be left alone. Wasn’t she? Ridiculous to still need a nanny at her age, but with two working parents on a series that demanded eighteen hour days, it helped to have someone who could drive and fix meals. But Julia could be left alone, couldn’t she? Besides, she was asleep. What could happen? It wouldn’t take me more than—what—twenty minutes. This time of night? No traffic? There and back in...forty-five minutes, tops. Better than waking her and taking her with me, having to explain where we were going and why.

I knew Jonathan wouldn’t approve. But he was in New York. And he didn’t have to write the script.

You’d have to be a writer to understand.

What if I left her and a fire broke out? Or a burglar broke in? A rapist, the Manson family, the men who killed the Clutters?

In Brentwood?

Why not? Sharon Tate was two canyons away.

The option of finishing the script without coke was not available. Not in those days.

The clock was ticking. It was almost one in the morning. The messenger was coming at six for the script.

I scribbled a note, left it by her bed next to her cell phone, closed the door softly, and left the house.

* * *

Fifty minutes later, I’m flying home. Almost two in the morning on a cold starless night on Coldwater Canyon in Beverly Hills. No sidewalks, only narrow shoulders, expensive homes hidden from view behind protective hedges. No street lamps, barely a moon. My headlights the only illumination on the twisting canyon road.

The taste Zeke had given me was amazing. In a flash of insight, I’d seen the whole last act. Everything Jinx Magruder would need to solve the case. It was perfect! How could I have missed it? It was all so clear. Beautifully and intricately connected, layers of meaning reverberating in on themselves. No wonder I used drugs!

I was watching the scenes play out when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw—what was it?—too late—to keep from hitting it.

The jolt of the impact threw me forward, slamming my chest into the wheel, as it spun the car into a skid. I straightened the wheel into the direction of the skid, and the car righted itself and continued careening down the canyon before my mind had registered what had happened.

I’d hit something. What had it been?

Who. Had it been.

I knew I should stop and find out.

But I had two grams of coke in the car. What if I had to wait for the police to file a report?

I rounded one curve and hurtled towards the next. A glance in the rear view mirror revealed only the familiar sight of a terrified woman struggling to appear okay. The road behind was empty.

I’d left Julia at home. If I stopped, Jonathan would find out.

I rounded the curves without downshifting, the downhill momentum increasing my speed. No lights. No sounds. Just the purr of the Porsche and the thud of whatever my fender hit, which now echoed in the blood pounding in my ears.

What had I hit? Stop, and find out.

What if I was arrested? Production would shut down, and we were already over budget. If I went to jail, it could cost us the season. People with families to feed would lose their jobs. It was irresponsible, selfish even to consider it. It must have been a dog.

I love dogs. I should stop and tell the owners.

It didn’t have tags. If it had, I would have seen them.

My sweaty hands gripped the wheel. My foot pressed the accelerator as if I could outpace what I had done. As if, if I just drove fast enough, I could get back to the time before I’d left the house.

Because in some part of my frenzied being, I knew it was no dog. Dogs don’t kneel by the side of the road to change their tires in the middle of the night.

I turned on the radio. And I remember now that as I fled down that dark, twisting canyon, eyes like pinwheels, brain on fire, the Beach Boys sang in celestial harmonies, “She’ll have fun, fun, fun, ‘til her daddy takes her T-Bird away.”