Читать книгу Fire and Hemlock - Diana Wynne Jones - Страница 7

2 O I forbid you, maidens all,That wear gold in your hair,To come or go by CarterhaughFor young Tam Lin is there. TAM LIN

ОглавлениеIn those days people who did not know Polly might have thought she chose Nina as a friend to set herself off by comparison. Nina was a big, fat girl with short, frizzy hair, glasses, and a loud giggle. Polly, on the other hand, was an extremely pretty little girl, and probably the prettiest thing about her was her mass of long, fine, fair hair. In fact, Polly admired and envied Nina desperately, both Nina’s looks and her bold, madcap disposition. Polly, at that time, was trying to eat a packet of biscuits every day in order to get fat like Nina. And she spent diligent hours squashing and pressing at her eyes in hopes either of making herself need glasses too, or at least of giving her eyes the fat, pink, staring look that Nina’s had when Nina took off her glasses. She cried when Mum refused to cut her hair short like Nina’s. She hated her hair. The first morning they were at Granny’s, she took pleasure in forgetting to brush it.

It was not hard to forget. Polly and Nina had been awake half the night in Granny’s spare room, talking and laughing. They were wildly excited. And it was such a relief to Polly to be away from the whispered quarrelling at home, and the hard, false silences whenever Mum and Dad noticed Polly was near. They did not seem to realise that Polly knew a quarrel when she heard one, just like anyone does. Granny was a relief because she was calm. Nina’s wild, silly jokes were even more of a relief, even if Polly was hardly awake the next morning. The whole first day at Granny’s was like a dream to Polly.

It was a windy day in autumn. In Granny’s garden the leaves whirled down. Nina and Polly raced about, catching them. Every leaf you caught, Nina shrieked, meant one happy day. Polly only caught seven. Nina caught thirty-five.

“Well, it’s a whole week. Count your blessings,” Granny said to Polly in her dry way when they came panting in to show her, and she gave them milk and biscuits. Granny always made Polly think of biscuits. She had a dry, shortbread sort of way to her, with a hidden taste that came out afterwards. Her kitchen had a biscuit smell to it, a nutty, buttery smell like no other kitchen.

While Polly was sniffing the smell, Nina remembered that today was Hallowe’en. She decided that she and Polly must both dress up as High Priestesses, and she clamoured for long black robes.

“Never a dull moment with our Nina,” Granny remarked, and she went away to see what she could find. She came back with two old black dresses and some dark curtains. In an amused, uncommitted way, she helped them both dress up. Then she turned them firmly out of doors. “Go and make an exhibit of yourselves round the neighbourhood,” she said. “They need a bit of stirring up here.”

Nina and Polly paraded up and down the road for a while. Nina looked for all the world like a large, fat nun, and the dress held her knees together. Polly’s dress, apart from being long, was quite a good fit. The neighbourhood did not seem to notice them. The houses – except for a few small ones like Granny’s – were large and set back from the road, hidden by the trees that grew down both sides, and not a soul came to see the two High Priestesses, even though Nina laughed and shrieked and exclaimed every time her headdress flapped. They paraded right up to the big house across the end of the road and looked through the bars of its gate. It was called Hunsdon House – the name was cut into the stone of both gateposts. Inside, they saw a length of gravel drive, much strewn with dead leaves, and, coming slowly crunching along it towards them, a shiny black motor-hearse with flowers piled on top.

At the sight Nina shrieked and ran away down the road, trailing her headdress. “Hold your collar! Hold your collar till you see a four-legged animal!”

They ran into Granny’s garden where, luckily, Granny’s black-and-white cat, Mintchoc, was sitting on the wall. So that was all right. They could use both hands again. “Now what shall we do?” demanded Nina.

Polly was still laughing at Nina. “I don’t know,” she said.

“Think of something. What do High Priestesses do?” said Nina.

“No idea,” said Polly.

“Yes you have,” said Nina. “Think – or I shan’t play with you any more!”

Nina was always making that threat. It never failed with Polly. “Oh – er – they walk in procession and make human sacrifices,” Polly said.

Nina shrieked with gleeful laughter. “We did! We have! Our corpse was in the hearse! Then what happens?”

“Um,” said Polly. “We have to wait for the gods to answer our sacrifice. And – I know – while we wait, the police come after us for murder.”

Nina liked that. She ran flapping and squawking into Granny’s back garden, crying out that the police were after her. When Polly caught up with her, she was trying to climb the wall into the next garden. “What are you doing?” Polly said, hardly able to speak for laughing.

“Escaping from the police, of course!” said Nina. With a great deal of silly giggling, she managed to scramble to the top of the wall, where her black robe split with a sound like a gunshot. “Oh!” she cried. “They got me!” Whereupon she swung her legs over the wall and vanished in a crash of rotting wood. “Come on!” said her voice from behind the wall. “I won’t be your friend if you stay there.”

As usual, the threat was enough for Polly. It was not really that she was afraid Nina would stop being her friend – though she was, a little. It was more that Polly could not seem to break out of her prim, timid self in those days, and be properly adventurous, without Nina’s threats to galvanise her. So now she boldly swung herself up the wall and was quite grateful to Nina when she landed in the middle of somebody’s woodshed on the other side.

After that, the morning became more like a dream than ever – a very silly dream too. Nina and Polly scrambled through garden after garden. Some were neat and open, and they sprinted through those, and some were overgrown, with hiding-places where they could lurk. One garden was full of washing, and they had to crouch behind flapping sheets while somebody took down a row of pants. They were on the edge of giggles the whole time, terrified that someone would catch them and yet, in a dreamlike way, almost sure they were safe. Both of them lost their curtain headdresses in different gardens, but they went on, quite unable to stop or go back, neither of them quite knowing why. Nina invented a reason in about the tenth garden. She said they were coming to a road, because she could hear cars. So they went more madly than ever, across a row of rotting shed roofs that creaked and splintered under them, and jumped down from the wall into what seemed to be a wood. Nina ran towards the open, laughing with relief, and Polly lost her for a few seconds.

When Polly came out into the open, it was not a road after all. It was gravel at the side of a house. There was a door open in the house, and through it Polly caught a glimpse of Nina walking up a polished passage, actually inside the house.

“The cheek Nina has!” she said to herself. For a moment she almost did not dare follow Nina. But the dreamlike feeling was still on her. She thought of the threats Nina would make if she stayed hiding in the wood, and she sprinted on her toes across the space in a scatter of gravel and went into the house too, into a strong smell of polish and scent. Cautiously, she tiptoed up the passage.

Here it was completely like a dream. The passage led into a grand hall with a white-painted staircase wrapped round the outside of it in joints, each joint a balcony, and huge, painted china vases standing around, every one big enough to contain one of Ali Baba’s forty thieves. A man met her here. As people do in dreams, he seemed to be expecting Polly. He was obviously a servitor, for he was wearing evening dress and carrying a tray with glasses on it. Polly made a little movement to run away as he came up to her, but all he said was, “Orangeade, miss? I fancy you’re a bit young yet for sherry.” And he held the tray out.

It made Polly feel like a queen. She put out a somewhat grubby hand and took a glass of orangeade. There was ice in it and a slice of real orange. “Thank you,” she said in a stately, queenlike way.

“Turn left through that door, miss,” the servitor said.

Polly did as he said. She had a feeling she was supposed to. True, underneath she had a faint feeling that this couldn’t be quite right, but there did not seem to be anything she could do about it. Holding the clinking glass against her chest, Polly walked like a queen in her black dress into a big, carpeted room. It was dingy in the gusty light of the autumn day, and full of comfortable armchairs lined up in not very regular rows. A number of people were standing about holding wineglasses and talking in murmurs. They were all in dark clothes and looked very respectable, and every one of them was grown up. None of them paid any attention to Polly at all.

Nina was not there. Polly had not really expected her to be. It was clear Nina had vanished the way people do in dreams. She saw the woman she had mistaken for Nina – it was the split skirt and the black dress which had caused the mistake – standing outlined against the dim green garden beyond the windows, talking to a high-shouldered man with glasses. Everything was very hushed and elderly. “And I shan’t look on it very kindly if you do,” Polly heard the woman say to the man. It was a polite murmur, but it sounded like one of Nina’s threats, only a good deal less friendly.

More people came in behind Polly. She moved over out of their way and sat on one of the back row of chairs, which were hard and upright, still carefully holding her orangeade. She sat and watched the room fill with murmuring, dreamlike people in dark clothes. There was one other child now. He was in a grey suit and looked as respectable as the rest, and he was rather old too – at least fourteen, Polly thought. He did not notice Polly. Nobody did, except the man with glasses. Polly could see the glasses flashing at her uncertainly as the lady talked to him.

Then a new stage seemed to start. A busy, important man swept through the room and sat down in a chair facing all the others. All the rest sat down too, in a quiet, quick way, turning their heads to make sure there was a chair there before they sat. The room was all rustling while they arranged themselves, and one set of quick footsteps as the high-shouldered man walked about looking for a place. Everyone looked at him crossly. He hunched a bit – you do, Polly thought, when everyone stares – and finally sat down near the door, a few seats along from Polly.

The important man flipped a large paper open with a rattle. A document, Polly thought. “Now, ladies and gentlemen, if I have your attention, I shall read the Will.”

Oh dear, Polly thought. The dream feeling went away at once, and the ice in her drink rattled as she realised where she was and what she had done. This was Hunsdon House, where she and Nina had seen the hearse. Someone had died here and she had gatecrashed the funeral. And because she was dressed up in a black dress, no one had realised that she should not be here. She wondered what they would do to her when they did. Meanwhile she sat, trying not to shake the ice in her glass, listening to the lawyer’s voice reading out what she was sure were all sorts of private bequests – from the Last Will and Testament of Mrs Mabel Tatiana Leroy Perry, being of a sound mind et cetera – which Polly was sure she should not be hearing at all.

As the lawyer’s voice droned on, Polly became more and more certain she was listening to private things. She could feel the way each item made sort of waves among the silent listeners, waves of annoyance, anger and deep disgust, and one or two spurts of quite savage joy. The disgust seemed to be because so many things went to “my daughter Mrs Eudora Mabel Lorelei Perry Lynn”. Even when things went to other people, such as “my cousin Morton Perry Leroy” or “my niece Mrs Silvia Nuala Leroy Perry”, the Will seemed to change its mind every so often and give them to Mrs Perry Lynn instead. The joy was on the rare occasions when someone different, like Robert Goodman Leroy Perry or Sebastian Ralph Perry Leroy, actually got something.

Polly began to wonder if it might even be against the law for her to be listening to these things. She tried not to listen – and this was not difficult, because most of it was very boring – but she became steadily more unhappy.

She wished she dared creep away. She was quite near the door. It would have been easy if only that man hadn’t chosen to sit down just beyond her, right beside the door. She looked to see if she still might slip out, and looked at the same moment as the man looked at her, evidently wondering about her. Polly hastily turned her head to the front again and pretended to listen to the Will, but she could feel him still looking. The ice in her drink melted. The Will went on to an intensely boring bit about “a Trust shall be set up”. Beside the door, the man stood up. Polly’s head turned, without her meaning it to, as if it were on strings, and he was still looking at her, right at her. The eyes behind the glasses met hers and sort of dragged, and he nodded his head away sideways towards the door. “Come on out of that,” said the look. “Please,” it added, with a sort of polite, questioning stillness.

It was a fair cop. Polly nodded too. Carefully she put the melted orange drink down on the chair beside hers and slid to the floor. He was now holding out his hand to take hers and make sure she didn’t get away. Feeling fated, Polly put her hand into his. It was a big hand, a huge one, and folded hers quite out of sight under its row of long fingers. It pulled, and they both went softly out of the door into the hall with the jointed staircase.

“Didn’t you want your drink?” the man asked as the lawyer’s voice faded to a rise and fall in the distance.

Polly shook her head. Her voice seemed to have gone away. There was an archway opening off the hall. In the room through the archway she could see the servitor setting wineglasses out on a big, polished dinner table. Polly wanted to shout to him to come and explain that he had let her into the funeral, but she could not utter a sound. The big hand holding hers was pulling her along, into the passage she had come in by. Polly, as she went with it, cast her eyes round the hall for a last look at its grandeurs. Wistfully she thought of herself jumping into one of the Ali Baba vases and staying there hidden until everyone had gone away. But as she thought it, she was already in the side passage with the door standing open on the gusty trees at the end of it. The lawyer’s voice was out of hearing now.

“Will you be warm enough outside in that dress?” the man holding her hand asked politely.

His politeness seemed to deserve an answer. Polly’s voice came back. “Yes thank you,” she replied sadly. “I’ve got my real clothes on underneath.”

“Very wise,” said the man. “Then we can go into the garden.” They stepped out of the door, where the wind wrapped Polly’s black dress round her legs and flapped her hair sideways. It could not do much with the man’s hair, which was smoothed across his head in an elderly style, so it stood it up in colourless hanks and rattled the jacket of his dark suit. He shivered. Polly hoped he would send her off and go straight indoors again. But he obviously meant to see her properly off the premises. He turned to the right with her. The wind hurled itself at their faces. “This is better,” said the man. “I wish I could have thought of a way to get that poor boy Seb out of it too. I could see he was as bored as you were. But he didn’t have the sense to sit near the door.”

Polly turned and looked up at him in astonishment. He smiled down at her. Polly gave him a hasty smile in return, hoping he would think she was shy, and turned her face back to the wind to think about this. So the man thought she really was part of the funeral. He was just meaning to be kind. “It was boring, wasn’t it?” she said.

“Terribly,” he said, and let go of her hand.

Polly ought to have run off then. And she would have, she thought, remembering it all nine years later, if she had simply thought he was just being kind. But the way he spoke told her that he had found the funeral far more utterly boring than she had. She remembered the way the lady she had mistaken for Nina had spoken to him, and the way the other guests had looked at him while he was walking about looking for a seat. She realised he had sat down on purpose near the door, and she knew – perhaps without quite understanding it – that if she ran away, it would mean he had to go back into the funeral again. She was his excuse for coming out of it.

So she stayed. She had to lean on the wind to keep beside him while they walked under some ragged, nearly finished roses and the wind blew white petals across them.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

“Polly.”

“Polly what?”

“Polly Whittacker,” she said without thinking. Then of course she realised that the right name for the funeral should have been Leroy or Perry, or Perry Leroy, or Leroy Perry, like the people who got the bequests in the Will, and had to cover it up. “I’m only adopted, you know. I come from the other branch of the family really.”

“I thought you might,” he said, “with that hair of yours.”

“And what part of the family are you?” Polly said, quickly and artificially, to distract him from asking more. She took a piece of her blowing hair and bit it anxiously.

“Oh, no part really,” he said, ducking his head under a clawing rose. “The dead lady is the mother of my ex-wife, so I felt I ought to come. But I’m the odd man out, here.” Polly relaxed. He was distracted. He said, “My name’s Thomas Lynn.”

“Both parts surname?” Polly asked doubtfully. “Everyone’s so double-barrelled in there.”

That made him give a little crow of laughter, which he swallowed hastily down, as if he were ashamed of laughing at a funeral. “No, no. Just the second part.”

“Mr Lynn, then,” said Polly. She let her hair blow round her face as they walked down some sunken steps, and studied him. Long hair had its uses. He was tall and thin and walked in a way that stooped his round, colourless head between his shoulders, making his head look smaller than it really was – though some of that could have been distance: he was so tall that his head was a long way off from Polly. Like a very tall tortoise, Polly thought. The glasses added to the tortoise look. It was an amiable, vague face they sat on. Polly decided Mr Lynn was nice.

“Mr Lynn,” she asked, “what do you like doing most?”

The tortoise head swung towards her in surprise. “I was just going to ask you that!”

“Snap!” said Polly, and laughed up at him. She knew, of course, by this time, that she was starting to flirt with Mr Lynn. Mum would have given Polly one of her long, heavy stares if she had been there. But, as Polly told herself, she did have to distract Mr Lynn from thinking too deeply about her connection with the funeral, and she did think Mr Lynn was nice anyway. Polly never flirted with anyone unless she liked them. So, as they edged their way between two vast grey hedges of uncut lavender, she said, “What I like best – apart from running and shouting and jokes and fighting – is being things.”

“Being things?” Mr Lynn asked. “Like what?” He sounded wistful and mystified.

“Making things like heroes up with other people, then being them,” Polly explained. The tortoise head turned to her politely. She could tell he did not understand. It was on the tip of her tongue to show him what she meant by telling him how she had arrived at the funeral by being a High Priestess with the police after her. But she dared not say that. “I’ll show you,” she said instead. “Pretend you’re not really you at all. In real life you’re really something quite different.”

“What am I?” Mr Lynn said obligingly.

It would have been better if he had been like Nina and said he would not be friends unless she told him. Without any prodding, Polly’s invention went dead on her. She could only think of the most ordinary things.

“You keep an ironmonger’s shop,” she said rather desperately. To make this seem better, she added, “A very good ironmonger’s shop in a very nice town. And your name is really Thomas Piper. That’s because of your name – Tom, Tom, the piper’s son – you know.”

Mr Lynn smiled. “Oddly enough, my father used to play the flute professionally. Yes. I sell nails and dustbins and hearth-brushes. What else?”

“Hot-water bottles and spades and buckets,” said Polly. “Every morning you go out and hang them round your door, and stack wheelbarrows and watering cans on the pavement.”

“Where passers-by can bark their shins on them. I see,” said Mr Lynn. “And what else? Am I happy in my work?”

“Not quite happy,” Polly said. He was playing up so well that her imagination began to work properly. Down between the lavender bushes, the wind was cut off and she felt much calmer. “You’re a bit bored, but that doesn’t matter, because keeping the shop is only what everyone thinks you do. Really you’re secretly a hero, a very strong one who’s immortal—”

“Immortal?” Mr Lynn said, startled.

“Well nearly,” said Polly. “You’d live for hundreds of years if someone doesn’t kill you in one of your battles. Your name is really – um – Tan Coul and I’m your assistant.”

“Are you my assistant in the shop as well, or just when I’m being a hero?” asked Mr Lynn.

“No, I’m me,” said Polly. “I’m a learner hero. I come with you whenever you go out on a job.”

“Then you’ll have to live within call,” Mr Lynn pointed out. “Where is this shop of mine? Here in Middleton? It had better be, so that I can pick you up easily when a job comes up.”

“No, it’s in Stow-on-the-Water,” Polly said decidedly. Pretending was like that. Things seemed to make themselves up, once you got going.

“That’s awkward,” Mr Lynn said.

“It is, isn’t it?” Polly agreed. “If you like, I’ll come and work in your shop and pretend to be your real-life assistant too. Say when I found out where you lived, I journeyed miles from Middleton to be near you.”

“Better,” said Mr Lynn. “You also pretended to be older than you are, in order not to be sent to school. But that sort of thing can easily be done by the right kind of trainee-hero, I’m sure. What’s your name when we’re out on a job?”

“Hero,” said Polly. “It is a real name,” she protested, as the tortoise head swung down to look at her. “It’s a lady in my book that I read every night. Someone swam the sea all the time to visit her.”

“I know,” said Mr Lynn. “I was just surprised that you did.”

“And it’s a sort of joke,” Polly explained. “I know a lot about heroes, because of my book.”

“I see you do,” said Mr Lynn, smiling rather. “But there are still a lot of things we need to settle. For instance—”

As he spoke, they pushed out from between the grey hedges into a small lawn with an empty sunken pool in it. A brown bird flew away, low across the grass as they came, making a set of sharp, shrieking cries. The wind gusted over, rolling the dry leaves in the concrete bottom of the pool, and a ray of sun followed the wind, travelling swiftly over the lawn.

“For instance,” said Mr Lynn, and stopped.

The sun reached the dry pool. For just a flickering part of a second, some trick of light filled the pool deep with transparent water. The sun made bright, curved wrinkles on the bottom, and the leaves, Polly could have sworn, instead of rolling on the bottom were, just for an instant, floating, green and growing. Then the sunbeam travelled on, and there was just a dry oblong of concrete again. Mr Lynn saw it too. Polly could tell from the way he stopped talking.

“Heroes do see things like that,” she said, in case he was alarmed.

“I suppose they do,” he agreed thoughtfully. “True. They must, since we both are. But, tell me, what happens when the call comes to do a job? I’m in the shop, selling nails. We each snatch up a saw – or I suppose an axe would be better – and we rush out. Where do we go? What do we do?”

They walked past the pool while Polly considered. “We go to kill giants and dragons and things,” she said.

“Where? Up the road in the supermarket?” Mr Lynn asked.

Polly could tell he thought poorly of her answer. “Yes, if you like, if you’re so clever!” she snapped at him, just as if he were Nina. “I know we’re that kind of heroes – I know we’re not the kind that conquers mad scientists – but I don’t know it all. You do some of it, if you know so much! You were just pretending not to know about being things – weren’t you?”

“Not altogether,” Mr Lynn said, politely holding a wet lump of evergreen bush aside for Polly. “It’s years since I did any. Beside you, I’m the learner. I’d really much prefer to be a trainee-hero too. Couldn’t I be? You could happen to be there when I kill my first giant – and perhaps it could be thanks to you that I didn’t get squashed flat by him.”

“If you like,” Polly agreed graciously. He was so humble that she felt quite mean to have snapped.

“Thank you,” he said, just as if she had granted a real favour. “That brings me to another question. Do I know about my secret life as a hero while I’m being an ironmonger? Or not?”

“You didn’t at first,” Polly said, thinking it out. “You were awfully surprised and thought you were having visions or something. But you got used to it quite quickly.”

“Though at first I blundered about, utterly bewildered,” Mr Lynn agreed. “We both had to learn as we went on. Yes, that’s how it must have been. Now, what about my life selling hardware in Stow-on-the-Water? Do I live alone?”

“No, I live there too, when I get there,” said Polly. “But of course there’s your wife, Edna—”

“No there isn’t,” Mr Lynn said. He said it quietly and calmly, as if someone had asked him if there was any butter and he had opened the fridge and found none. But Polly could tell he meant it absolutely.

“Well – there has to be,” she argued. “There’s someone – I know her name’s Edna – who bosses you round, and makes your life a misery, and thinks you’re stupid, and doesn’t allow you enough money, and makes you do all the work—”

“My landlady,” said Mr Lynn.

“No,” said Polly.

“Sister, then,” said Mr Lynn. “How about a sister?”

“I don’t know about sisters!” Polly protested.

They wandered round the overgrown garden, arguing about it. In the end, Polly found she had to give way about Edna and make her a sister after all. Mr Lynn was just quietly adamant over it, and he would not budge. He gave in to Polly on most other things, but not on that.

“Must I kill dragons?” he said, rather pleadingly, as they came up to the house from the back somewhere.

“Yes,” said Polly. “It’s what our kind of heroes do.”

“But most dragons seem to have rather interesting personalities – besides probably having quite good reasons for what they do, if only one could understand them,” Mr Lynn objected. “And almost every dragon-slayer I ever heard of came to a sticky end in the end.”

“Don’t be a coward,” said Polly. “St George in my book didn’t come to a sticky end.”

“I’m nothing like St George,” said Mr Lynn. “He didn’t wear glasses.”

This was true, even though Polly had always imagined St George as tall and thin like Mr Lynn. He seemed so unhappy that she relented a little. “We’ll keep the dragon to the end, then, for when we’re properly trained.”

“That’s a good idea,” Mr Lynn said gratefully. “Now come over here. There’s something I think you’ll like.”

He led the way up the lawn, against the gusts of the wind, right up to the house. Three stone steps there led up to a closed door. On either side of the steps there was a short stone pillar with a stone vase on top of it. Mr Lynn stretched his arms out so that he had a hand on each stone vase. “Are you looking?” he said, standing in his bowed way between them. Like Samson in my book, Polly thought, getting ready to pull the temple down.

“Yes,” she said. “What?”

“Watch.” Mr Lynn’s hand moved on the right-hand vase. The vase began to spin slowly, grating a little. Two, three heavy turns and it stopped. Now Polly could see there were letters engraved on the front of the vase.

“HERE,” she read.

“Now watch again,” said Mr Lynn. His big left hand spun the other vase. This one went round much more smoothly. For a while it was a grey stone blur. Then it grated, slowed, and settled, and there were letters on it too.

“NOW,” Polly read. “NOW – HERE. What does that mean?”

Mr Lynn spun both vases, one slowly, grinding and groaning, the other smooth and blurring. They both stopped at exactly the same time.

WHERE, said the one on the left. NOW, read the right-hand one.

Upon which, Mr Lynn spun them again. This time when they stopped, the vases read NO and WHERE.

“Oh I see!” said Polly. “NOWHERE! That’s clever!” She moved sideways to look round the curve of the vases and found they still said NOWHERE, though this was because the left-hand vase now seemed to say NOW and the right-hand one HERE from where she had moved to. Both vases really said NOWHERE, but the letters were so arranged on them that you could never see the whole word at once on the same vase. Polly made sure, by going right up to them, ducking under Mr Lynn’s arm, and putting her head sideways to read the letters round the other side.

“Yes that’s right,” Mr Lynn said. “They both say NOWHERE really.” He spun them again, the slow grinding one and the fast smooth one, and this time they came up with HERE – NOW.

“Heroes see things like that,” he said.

“It’s obviously an enchantment of some kind,” Polly agreed, humouring him.

“It must be,” he said. It sounded as if he was humouring her.

Here, they both looked round, Polly was not sure why. The boy who had been at the funeral was standing behind them, still very smooth and neat in spite of the wind. Maybe he had snorted. At any rate, he was looking very scornful.

“Oh hello, Seb,” Mr Lynn said. “You got out at last, then?”

“Only because it’s over,” the boy said contemptuously.

“Is it? Thank goodness for that!” Mr Lynn said.

Instead of answering, the boy simply turned round and walked away. Mr Lynn’s face, Polly thought, showed just a trace of hurt feelings.

“What a horrible, rude boy!” Polly exclaimed, hoping it was loud enough for the boy to hear as he walked. But he walked very quickly and was out of sight round the corner of the house before she had finished saying it. “What relation is he?” she asked.

“Son of Laurel’s cousin – distant enough,” Mr Lynn said. He stood looking the way the boy had gone, in an absent, unhappy way that made Polly uncomfortable. But when he looked down at her, he seemed quite cheerful. “I think we could risk going back in again now,” he said. “They tell me I’m allowed to choose some of the old lady’s pictures. Would you like to help me choose?” He held out his hand to Polly and smiled.

Polly almost took hold of it. Then she backed away. Mr Lynn stayed with his hand awkwardly stretched out, and the smile died off his face, leaving it perplexed and a good deal more hurt than he had looked over Seb’s rudeness. “What’s the matter?” he asked.

It made Polly feel mean as well as dishonest. “I’m not a relation,” she blurted out. She could feel her cheeks stinging as they turned red. “I came in by mistake. I thought Nina was in there – being silly, you know.”

“I had an idea it was something like that,” Mr Lynn said rather sadly. “So you’re not coming?”

“I – I will if you want me to,” Polly said.

“I’d be very much obliged if you would,” said Mr Lynn.

His hand was still stretched out. Polly took hold of it, quite extraordinarily glad to have told him the truth, and they went on round the house the way Seb had gone.

“So my first giant is to be in the Stow-Whatsis supermarket,” Mr Lynn said as they turned the corner.

“Quite a small one, or he wouldn’t fit,” Polly said consolingly. This side of the house was the grand front. There was a large space of gravel with cars parked in it. These must have been the cars they had heard which had made Nina think they were coming to the road. Polly wondered where Nina was, but she was far too interested in her own adventures to worry about Nina. Numbers of people, dark-dressed and sober from the funeral, were drifting out of the open front door of Hunsdon House and wandering about on the gravel. Some seemed to have come out for fresh air. Some were getting into cars to leave.

Polly and Mr Lynn went along the side of the house to the front door. “Even a small one would get into the local papers,” Mr Lynn said. “What do we say to the reporters?”

“Leave all the interviewing to me,” Polly said grandly.

Perhaps it was a strange conversation. Perhaps this accounted for the unfriendly looks they got from the people round the front door. Some pretended not to notice Polly and Mr Lynn. Others said, “Hello, Tom,” but they said it in a grudging sort of way, and raised their eyebrows at Polly before they turned away. By the time she and Mr Lynn had edged their way inside into the grand hall again, Polly was sure this had nothing to do with their conversation. The people crowding the hall, she could somehow tell, were the most important members of the family. Every one of these gave Mr Lynn a disapproving look – if they bothered to notice him at all – before turning away. Before they had pushed their way halfway across to the stairs, Polly did not wonder that Mr Lynn had wanted her to keep him company indoors.

The one person who spoke to Mr Lynn was a man Polly did not like at all. He turned right round, in the middle of talking to someone else, in order to stare at Mr Lynn and Polly. He was a big, portly person with a dark, pouchy piece of skin under each eye.

“Slithering off as usual, are you, Tom?” he said jovially. It was not nearly as jolly as it sounded.

“No, I’m still here, Morton, as you see,” Mr Lynn said, ducking his head apologetically.

“Then stick around,” the man said, “or you’ll be in real trouble.” He laughed, to pretend it was a joke. It was a deep, chesty laugh. Polly thought of it as a fatal laugh, the way you think about a bad cough. The man turned away, laughing this chesty laugh. “Laurel told me to tell you,” he said, and went back to talking to the person he had turned away from.

“Thanks,” Mr Lynn said to his back, and towed Polly on across the hall.

They had reached the foot of the jointed staircase when the servitor politely stopped them. “I beg your pardon, sir. Will you or the little girl be staying for lunch?”

“I don’t—” Mr Lynn began. He stopped and looked down at Polly, rather dismayed. He had obviously forgotten she was not supposed to be there. “No,” he said. “We’ll be leaving almost at once, thank you.”

The servitor said, “Thank you, sir,” and went away.

Polly did not blame Mr Lynn for not doing what the laughing man had told him to do. “Who was that man?” she whispered as they went up the stairs.

“One of the caterers, I think,” said Mr Lynn.

“No, silly! The one with black poached eyes,” Polly whispered.

That made Mr Lynn utter a yelp of laughter, guiltily cut short. “Oh, him? That’s Seb’s father, Morton Leroy. He and Laurel are probably going to get married. The pictures are in here.”

Polly had hoped that they would be going right up the stairs, round all the joints, so that she would have a chance to investigate the upstairs of Hunsdon House. But the room Mr Lynn went into was off a half-landing, only one short flight up. It was a small, bare place. There were marks on the carpet where furniture had stood for a long time and then been taken away. The pictures were leaning against the walls to left and right, in stacks.

“Some of these, as I remember, were very nice,” Mr Lynn said. “Suppose we lean all the ones we think are worth taking against the wall under the window, and then consider which to take. I was told I could have six.”

As soon as they started looking at the pictures, Polly discovered that the ones leaning on the left-hand wall were by far the most interesting. She left Mr Lynn to sort through the ones on the other side of the room, and knelt facing the left wall, using her chin and stomach to prop the front pictures on while she leafed over the ones behind like the pages of a heavy book. She found a green, sunlit picture of old-fashioned people having a picnic in a wood, in a pile that was otherwise only saints with cracked gold paint on their halos. The next pile had a strange, tilted view of a fairground, a lovely Chinese picture of a horse, and some sad pink-and-blue Harlequins beside the sea. Polly put all these against the end wall at once. The one on top of the third pile she liked too. It was a swirly modern painting of people playing violins. Underneath that was a big blue-green picture of a fire at dusk where smoke was beginning to wreathe round the vast skeleton of a plant like cow parsley in front. Polly exclaimed with delight at it.

Meanwhile, Mr Lynn was saying, “I don’t remember half these pictures. Take a look at this. Dismal, isn’t it?”

Polly swivelled round to be shown a long brownish picture, more like a drawing, of a mermaid carrying a dead-looking man underwater. “It’s awful,” she said. “They’ve got silly faces. And the man’s body is too long.”

“I agree,” said Mr Lynn, “though I think I may take it as a curiosity. Explain how you got into this house by mistake.”

Polly got up and carefully carried the violin picture and the smoke picture to the end wall. “Nina started it,” she said. “But I got just as silly.” And she told him about the High Priestesses, and how they had climbed out of Granny’s garden into all the others. “Then we had to hide behind some sheets on the washing line,” she was saying, when she saw Mr Lynn stand up and, in a flurried sort of way, brush at the knees of his suit.

“Oh hello, Laurel,” he said.

The lady Polly had mistaken for Nina was standing in the doorway. Seen this close, she struck Polly as plump and quite pretty, and her black clothes were obviously very expensive. Her hair was rather strange, light and floating, of a colour that could have been grey or no colour at all. Polly somehow knew from all this, and most of all from a powerful sort of sweetness about this lady, that she was the one who had inherited almost everything in the house. And from the stiff way Mr Lynn was standing there, she also knew that Laurel was the ex-wife he had talked about. She just could not think how she had taken her for Nina.

“Tom, didn’t you know I’d been asking for you?” Laurel said. Then before Mr Lynn could do more than begin to shake his head – he was going to lie about that, Polly noticed with interest – Laurel’s eyes went first to the pictures and then to Polly. Polly jumped as the eyes met hers. They were as light as Laurel’s hair, but with black rings in the lightness, which made them almost seem like a tunnel Polly was looking down. They had no more feeling than a tunnel, either, in spite of the sweet look on Laurel’s face.

“When you choose your pictures, Tom,” Laurel said, looking at Polly, “don’t forget that the ones you can have are the ones over there.” Light caught colours from her rings as her hand pointed briefly to the right-hand wall. “The ones against the other wall are all too valuable to go out of the family,” she said.

Then she turned round and went out onto the landing, somehow taking Mr Lynn out there along with her. They half shut the door. Polly stood by the window and heard snatches of the things they said beyond the door. First came Laurel’s sweet, light voice saying “…all asking who the child is, Tom.” To which Mr Lynn’s voice muttered something about “…in charge of her… couldn’t just leave her…” She could tell Laurel did not like this, because she seemed pleased when Mr Lynn added “…away shortly. I’ve a train to catch.” One thing was clear: Mr Lynn was very carefully not telling Laurel who Polly was or how she got there.

Polly leaned against the window, looking down at the cars on the gravel, and considered. She was scared. She had thought it would be all right to come back into the house if Mr Lynn asked her to. Now she knew it was not. Mr Lynn was having to be artful and vague in order to cover it up. Laurel was frightening. Polly could hear her arguing with Mr Lynn now, out on the landing, her voice all little angry tinkles, like ice cubes in a drink. “Tom, whether you like it or not, you are!” And a bit later: “Because I tell you to, of course!” And later still: “I know you always were a fool, but that doesn’t let you off!”

Listening, Polly began to feel angry as well as scared. Laurel was a real bully, for all her voice was so sweet. Polly went over to the pictures on the other side of the room, the ones Mr Lynn was allowed to have. Sure enough, as she had expected, they were nothing like as good as the ones on the left-hand side. Most of them were terrible. Since the argument was still going on, outside on the landing, Polly tiptoed back to the pictures she had leaned against the wall by the window. Back and forth she tiptoed, putting all the good, interesting pictures she had already chosen into the stacks against the right-hand wall, and a few, not so terrible, to lean on the wall by the window, to look as if they had been chosen.

Then, to make things look the same as before, she took terrible pictures from the right-hand wall to the left-hand stacks. They ended up a complete mixture. When Mr Lynn came back into the room, Polly was kneeling virtuously by the right-hand wall, taking her mind off her evil deed by studying a picture called The Vigil, of a young knight praying at an altar.

“Do you think he’s a trainee-hero?” she asked Mr Lynn.

“Oh no. Put that back,” he said. “Don’t you think it’s soppy?”

“It is a bit,” Polly agreed cheerfully, and watched Mr Lynn choose pictures through her hair while she slowly put The Vigil back.

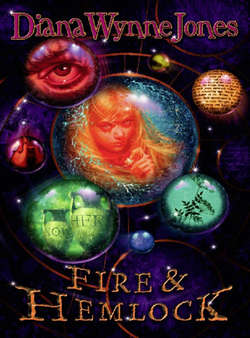

That was how she got Fire and Hemlock, of course. When he sorted through the doctored stacks, Mr Lynn picked out every one of the pictures Polly had chosen. “I didn’t know this would be here!” he said, and, “Oh, I remember this one!” He was particularly pleased by the swirly one of the violins. When he came to the picture of the fire at dusk, he smiled and said, “This photograph seems to haunt me. It used to hang over my bed when I lived here. I always liked the way the shape of that hemlock echoes the shape of that tree in the hedge. Here,” he said, and put it in Polly’s hands. “You have it.”

Polly was awed. She had never owned a picture before. Nor had she expected to profit from her bad deed. “You don’t mean I can keep it?” she said.

“Of course you can,” said Mr Lynn. “It’s not very valuable, I’m afraid, but you’ll find it grows on you. Keep it instead of a medal for life-saving.” At this, Polly tried to say thank you properly, but he cut her short by saying, “No, come on. I think your Granny may be worried about you by now.”

Mr Lynn had to carry the picture, along with his five others. It bumped against Polly’s legs as she walked, which threatened to break the glass. The other funeral guests were having lunch by then. Polly could hear the chink of knives and forks as they hurried through the empty hall. Polly was glad. She knew, if they met Laurel on the way out, Laurel would know at once that Mr Lynn had all the wrong pictures.

Thinking of Laurel, as she trotted beside Mr Lynn down the windy road, caused Polly, for some reason, to say, “When I come to work as your assistant in your ironmonger’s shop, I’m going to pretend to be a boy. You pretend you don’t know.”

“If you want,” said Mr Lynn. “As long as that doesn’t mean cutting your lovely hair.”

The lovely hair was blowing round Polly’s face and getting in her mouth and eyes. “It’s not lovely hair!” she said crossly. “I hate it. It drives me mad and I want it cut!”

“I’m sorry,” said Mr Lynn. “Of course. It’s your hair.”

“Oh!” said Polly, exasperated for no real reason. “I do wish you’d stop agreeing all the time! No wonder people bully you!” They came to Granny’s front gate then. “You can give me my picture now,” Polly said haughtily.

Mr Lynn did not reply, but he looked almost haughty too as he passed the picture over. The silence was all wind blowing and leaves rattling, and most unfriendly. But Granny had clearly been looking out for Polly. As Polly hitched the picture under her armpit and managed to get the gate unlatched, the front door banged open. Mintchoc came out first. For some reason, she put her back and tail up and fled at the sight of them. Granny sailed out second, like a rather small duchess.

“Inside, please, both of you,” she said. “I want to know just where she’s been.”

Polly and Mr Lynn stopped giving one another haughty looks and exchanged guilty ones instead. Humbly they followed Granny indoors and through to the kitchen. There sat Nina, over a half-eaten plate of lunch, staring wide-eyed and full-mouthed. By heaving a whole mouthful across into one side of her face, Nina managed to say, “Where did you go?”

“Yes,” said Granny, crisp as a brandy-snap. “That’s what I want to know too.” She stared long and sharp at Mr Lynn.

Mr Lynn shifted the heavy pile of pictures to his other arm. His glasses flashed unhappily. “Hunsdon House,” he admitted. “She – er – she wandered in. There’s a funeral there today, you know. She – er – I thought she looked rather lost while they were reading the Will, but as she was wearing black, I didn’t gather straightaway that she shouldn’t have been there. After that, I’m afraid I delayed her a little by asking her to help me choose some pictures.”

Granny’s sharp brown stare travelled over Mr Lynn’s lean, dark suit and his black tie and possibly took in a great deal. “Yes,” she said. “I saw the hearse go down. A woman, wasn’t it? So Madam gate-crashed the funeral, did she? And I’m to take it you looked after her, Mr – er?”

“Well he did, Granny!” Polly cried out.

“Lynn,” said Mr Lynn. “She’s very good company, Mrs – er?”

“Whittacker,” Granny said grimly. “And of course I’m very grateful if you kept her from mischief—”

“She was quite safe, I promise you,” said Mr Lynn.

Granny went on with her sentence as if Mr Lynn had not spoken. “—Mr Lynn, but what were you up to there? Are you an art dealer?”

“Oh no,” Mr Lynn said, very flustered. “These pictures are just keepsakes – for pleasure – that old Mrs Perry left me in her Will. I know very little about paintings – I’m a musician really—”

“What kind of musician?” said Granny.

“I play the cello,” said Mr Lynn, “with an orchestra.”

“Which orchestra?” Granny asked inexorably.

“The British Philharmonic,” said Mr Lynn.

“So then how did you come to be at this funeral?” Granny demanded.

“Relation by marriage,” Mr Lynn explained. “I used to be married to Mrs Perry’s daughter – we were divorced earlier this year—”

“I see,” said Granny. “Well thank you, Mr Lynn. Have you had lunch?” Though Granny said this most unwelcomingly, Polly knew Granny was relenting. She relaxed a little. The way Granny was interrogating Mr Lynn made her most uncomfortable.

But Mr Lynn remained flustered. “Thank you – no – I’ll get something on the station,” he said. “I have to catch the two-forty.” He managed somehow to haul up one cuff, and craned round the bundle of pictures to look at his watch. “I have to be in London for a concert this evening,” he explained.

“Then you’d better run,” said Granny. “Or is it Main Road you go from?”

“No, Miles Cross,” said Mr Lynn. “I must go.” And go he did, nodding at Polly and Nina, murmuring goodbye to Granny, and diving through the house in big strides like a laden ostrich. The front door slammed heavily behind him. Mintchoc came back in through her cat-flap in the back door. Granny turned to Polly.

“Well, Madam?”

Polly had hoped the trouble was over. She found it had only begun. Granny was furious. Polly had not known before that Granny could be this angry. She spoke to Polly in sharp, snapping sentences, on and on, about trespassing and silliness and barging in on private funerals, and she said a lot about each thing. But there was one thing she snapped back to in between, most fiercely, over and over again. “Has nobody ever warned you, Polly, never to speak with strange men?”

This hurt Polly’s feelings particularly. About the tenth time Granny asked it, she protested. “He isn’t a strange man now. I know him quite well!”

It made no impression on Granny. “He was when you first spoke to him, Polly. Don’t contradict.” Then Polly tried to defend herself by explaining that she’d thought she was following Nina. Nina began making faces at Polly, winking and jerking and twisting her food-filled mouth. Polly had no idea what Nina had told Granny, and she saw she was going to get Nina into trouble as well. She said hurriedly that Mr Lynn had taken her out of the funeral into the garden.

Granny did indeed shoot Nina a look sharp as a carving knife, which stopped Nina’s jaws munching on the spot, but she only said, “Nina’s got more sense than to walk into people’s houses where she doesn’t belong, I’m glad to see. But this Mr Lynn took you back indoors again, didn’t he? Why? He must have known by then that you didn’t belong.”

Granny seemed to know it all by instinct. “Yes. I mean, no. I told him,” Polly said. And she knew it had somehow been wrong to go back into the house, even if she had not made it worse by rearranging the pictures.

She thought of Laurel’s scary eyes, and the way Mr Lynn had been careful not to explain to Laurel who Polly was, and she found she could not quite be honest herself. “He needed me to choose the pictures,” she said. “And he gave me this one for my own.”

“Let’s see it,” said Granny.

Polly held the picture up in both hands. She was sure Granny was going to make her take it back to Hunsdon House at once. “I’ve never had a picture of my own before,” she said. Mintchoc, who was a most understanding cat, noticed her distress and came and rubbed consolingly round her legs.

“Hm,” said Granny, surveying the fire and the smoke and the hemlock plant. “Well, it isn’t an Old Master, I can tell you that. And Mr Lynn gave it you himself? Without you asking? Are you sure?”

“Yes,” said Polly. This was the truth, after all. “It was instead of a medal for life-saving.”

“Very well,” Granny said, to Polly’s immense relief. “Keep it if you must. And you’d better get that old dress off you and some lunch inside you before it’s time for tea.”

Nina was on pudding by the time Polly was ready to eat, and Mintchoc came and stationed herself expectantly between them. Mintchoc had got her name for being frantically fond of mint-chocolate ice cream, which was what Nina had for pudding. But Mintchoc liked cottage pie too.

“It was a very respectable funeral,” Polly explained as she started on her cottage pie. “Boring really.”

“Respectable!” Granny said, plucking Mintchoc off the table.

“And I like Mr Lynn,” Polly said defiantly.

“Oh, I daresay there’s no harm in him,” Granny admitted. “But you don’t go in that house again, Polly. What kind of respectable people choose to get buried on Hallowe’en?”

“Perhaps they didn’t know the date?” Nina suggested.

Granny snorted.

Later that day Granny and Nina had helped Polly bang a picture hook into the wall and hang the picture above Polly’s bed, where she could see it when she lay down to sleep. It had hung there ever since. Polly remembered staring at it while Nina clamoured to be told about her adventures. Polly did not want to tell Nina. It was private. Besides, she was busy trying to make out whether the shapes in the smoke were really four running people or only people-shaped lumps of hedge. She put Nina off with vague answers and, long before Nina was satisfied, Polly fell asleep. She dreamed that the Chinese horse from one of Mr Lynn’s other pictures had somehow got into her photograph and was trampling and rearing behind the fire and the smoke.