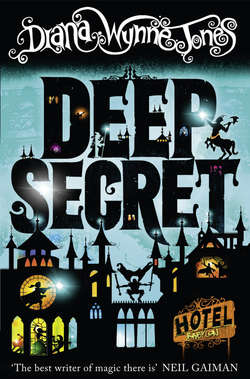

Читать книгу Deep Secret - Diana Wynne Jones - Страница 12

Оглавление

From Maree Mallory’s

Thornlady Directory, extracts

from various files

[1]

OK. So I’ve been behaving badly to Janine. As usual.

Janine was furious when I had to move in with them. She was so poisonous that I said to her, “You try living with your husband’s sister down the road! You try to write essays that are supposed to count towards your degree with seventeen children yelling round you!” My dad’s sister Irene has five kids of her own and two from her latest husband, but she finds life too quiet unless each of them has at least one little friend staying the night every night. Fortunately, the last thing my little fat dad did before they carted him off for chemotherapy – apart from giving me his car, that is – was to get on to his brother Ted and make Ted promise to house and feed me. So I told Janine to take her objections to Uncle Ted.

She said, “What’s wrong with university accommodation?”

“No room,” I said. “I was in a flat, but it was let over my head.”

That’s actually not quite what happened, but I wasn’t going to tell Janine. Robbie was sharing the two rooms with me (that I had used all my money paying for in advance) and then he just coolly moved his new bint Davina in instead of me. Or he said I could sleep on the sofa, I believe, though I may be wrong because I was too angry to listen at the time. I stormed off to Mum’s in London, swearing never to come back. And I meant it too, until Dad made me. He made me go back and I had to spend one glorious month in Aunt Irene’s house. And I told Dad, “Never again!” about that too, which is why he fixed things up with Uncle Ted.

Janine looked daggers at me. But she doesn’t go against Uncle Ted. If she did, he might notice the way she manages him. She’s going to bide her time and wait to work Uncle Ted round to thinking I’m impossible. So she did that thing she does, of pulling down the sleeves of her sweater so that her gold bangles jangle. Tug. Tug. Toss impeccable hair. Go away, clack, click, clack, to start phoning the unfortunate girls who mind the clothes shop she owns up in Clifton. She’s still sacking them for practically no reason. I heard her say to the phone as I went upstairs with another load of my stuff. “She’ll have to go. I’ve had quite enough of her.” She gets those awful sweaters she wears through that shop of hers. The one I hate most is the one she was wearing then, that looks as if she’d spilt rice-pudding over one shoulder. Nick says he hates the one with the bronze baked beans most.

And Janine thinks I’ll corrupt Nick! Or steal his affections or something. You couldn’t. No one could. Nothing can influence Nick unless he wants it to. Nick is sweetly and kindly and totally selfish. It says volumes that I never once set eyes on Nick while I was living just down the road with Aunt Irene. I asked him why when I was bringing my stuff into Uncle Ted’s house.

“That house is full of children!” he said, surprised that I should wonder. Nick himself, I should point out, is all of fourteen. He stood with his hands in his pockets watching me unload boxes and plastic bags from Dad’s car. “You’ve got a computer,” he observed. “Mine’s a laptop. What’s yours?”

“Old and cranky and incompatible with almost everything – just like me,” I said.

He actually picked it up and carried it to the top of his parents’ house for me. I think he was doing me an honour – that, or he was afraid I’d break it. He has a low opinion of women (well, so would I have with a mother like Janine). Then he came down again and looked at Dad’s car. “It’s quite nice,” he said.

“It’s my dad’s,” I said. “Or was. He said I could have it after I passed my driving test.”

“When did you pass?” he said.

“Hush,” I said. “I don’t take it till Monday.”

“Then how did you get it to Bristol?” he wondered.

“How do you think?” I said. “Drove it of course.”

“But—” he began. “All alone?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

I could see I had awed Master Nick. This pleased me. You have to keep someone like Nick suitably humble or you end up washing his socks while he walks barefoot all over you. (Robbie was the same, but I didn’t manage to awe him for long enough.) Nick has both his parents just where he wants them. I was delighted and highly chuffed to discover that Janine actually washes Nick’s socks by hand for him, because Nick claims to get sore feet if she doesn’t. Uncle Ted hands Nick ten-pound notes more or less whenever they pass on the stairs. And Nick has the whole basement of the house to himself. His parents have to knock before they come in. Honestly. He showed me his basement after I’d got all my things to the attic. I think that was another honour. It’s like a luxury flat down there, with all-over plum-coloured carpeting. And as for his sound system! Yah! Envy!

“I chose the carpet myself,” he said.

“Lovely funereal colour,” I said. “Like a bishop’s vest with mildew. You could spill whole jars of blackberry jam here and never notice.”

Nick laughed. “Why are you always so gloomy?”

“Because I’ve been crossed in love,” I told him. “Don’t push me about it. I get dangerous.”

“But you’re always dangerous,” he said. “That’s why I like you.”

Yes, Nick and I are getting on very well. Maybe this is why Janine objects to me. We seem to have been able to take up our old relationship exactly where it stopped when my parents divorced and moved to London. It goes way back, with me and Nick, to the time when Janine used to pay my mum to take care of Nick most of the time for her. The trouble was, Mum doesn’t go for babies (though she’s pretty good with teenagers, I’m here to tell you) and she used to push Nick off on to me as soon as I got home from school. Some of my earliest memories are of reaching up to push Nick’s great tall pushchair up the hill to the Downs, and when I’d toiled all the way up there, I used to fetch him out and we’d sit on the grass and invent stories. My first really bitchy row with Janine was when I was twelve and Nick was six and Janine discovered that Nick would rather be with me than go anywhere with her. She said I was putting fantasies into Nick’s head. I told her Nick was inventing most of them himself. She said he didn’t know truth from reality because of me. And I said that yes he did, because he knew he would be bored going out with her.

I suppose it helps pick up the old relationship that Nick is still exactly the same startlingly good-looking child he was when I wheeled him up the hill and old ladies used to stop me and say what a beautiful little brother I’d got (and I always said, “He’s not my brother, he’s my cousin”). Except that these days he’s about a yard taller and I have to crane upwards to see his face. He says I haven’t changed either. He’s right. I haven’t grown since I was twelve. And still the same round face, like a badly drawn heart on a school Valentine, and my nose never grew either, so my specs slide off all the time like they always did. Same mousy mane of hair, same lack of figure. And I did a lot of comfort-eating while I was with Mum (like a fool, I thought health foods were invented to stop people putting on weight) so now I’m truly FAT – and I always was on the plump and dumpy side. I looked in the mirror before I wrote this and wondered how Robbie ever fancied me…

[2]

…told me I’d failed my driving test. Well, it’s not my fault. Bristol is so confusing. I don’t think he should fail me just for getting us lost, though I did end up running backwards down Totterdown (I think the gradient is 1:5 there) because I couldn’t seem to remember how to do a hill start. Now I shall have to wait another month before I can take the test again. Pah.

I relieved my feelings by storming into the Vet Dept and applying to change to Philosophy. They said I was doing quite well and did I mean it. And I said yes. If they thought I was going to stick around watching Robbie Payne make sheep’s eyes at Davina Frostick, they thought wrong. They said that wasn’t a good reason to switch subjects. I said it was the only real one. So they ummed and aahed and said it wasn’t possible until after Easter, or maybe even until autumn, and obviously assumed I’d have changed my mind by then.

I WON’T. I’d let my fingernails grow while I was looking after Dad. Now I swear not to cut them for a year. They can’t make me do work on animals with six-inch talons. So.

Oh FRUSTRATION!!! Applying for a new driving test took nearly all the money I had left. I had to tell Uncle Ted I’d pay him for my bed and board every six months. He took it well. He’s pretty rich anyway. And Janine seems to be made of money.

But God those two are so boring!

I don’t blame Nick for diving away into that basement of his every evening. Before I got it sorted out that I could go away to my attic and pretend to work, I spent several centuries-long evenings sitting in their living room with them after supper (hm. Supper. Janine doesn’t cook, you know. She has what she calls her menus in the freezer, pre-packaged slenderisers. Nick and Uncle Ted eat them with ten-inch-high piles of reconstituted potatoes. She and I just eat them. I keep myself awake rumbling with hunger every night, but it must be worth it). They never go out after supper. Apparently Uncle Ted once got struck with an idea for a book in the middle of the Welsh National Opera and they had to leave so that he could go and write Chapter One. Janine is opposed to wasting money like that, so they stay in now. They almost never watch television because it interferes with Uncle Ted’s ideas.

So there we sat. Now you’d think that a world-famous author like Uncle Ted would be really interesting to talk to. The very least you’d expect was that he’d discuss the vileness of his latest demons (no one does demons like Uncle Ted: they’re really horrific). But not a bit of it. He doesn’t talk about his work at all, or anything to do with it.

I asked him why, the second evening. Janine looked at me as if I’d remarked that the Pope was into voodoo. And Uncle Ted said he saved that kind of talk for public appearances. “Writing’s a job, like any other,” says he. “I like to come home from the office and put my feet up, as it were.” (He works at home of course.)

“Well, it’s a point of view,” I said. Actually I was scandalised. Nothing to do with the imagination should be just “a job”. My opinion of Uncle Ted, whom I’ve always rather liked and admired, went screeching downhill almost to zero.

Then it went down again, in a steady depressed trundle, like a sledge on a very small slope, because Uncle Ted started talking about the house. And money. Looking very satisfied with how much money he’d made lately, he told me just which bit of redecoration or alteration he’s paid for out of which book. And Janine nodded enthusiastically and reminded him that Nick’s basement came out of The Curse on the Cottage; and he retorted with the fitted bookcases out of Surrender, You Devil; and they both told me that after Shadowfall they were able to afford an interior decorator to revamp the living room. I thought that was an awful way to look at a book. I thought a book was a Work of Art.

“But we left the windows in all the rooms as they are,” Uncle Ted added. “We had to.”

Now I had been fascinated by the glass in the windows. I remember it from when I was small. It waves and it wobbles. When you look out at the front – particularly in the evenings – you get a sort of cliff of trees and buildings out there, with warm lighted squares of windows, which all sort of slide about and ripple as if they are just going to transform into something else. From some angles, the houses bend and stretch into weird shapes, and you really might believe they were sliding into a set of different dimensions. From the back of the house it’s just as striking. There you get a navy blue vista of city against pale sunset. And when the streetlights come on they look like holes through to the orange sky. With everything rippling and stretching, you almost think you’re seeing your way through to a potent strange place behind the city.

I knew Uncle Ted was going to destroy all the strangeness by saying something dreary about his windows, and I terribly didn’t want him to. I almost prayed at him not to. But he did. He said, “It’s genuine wartime glass from World War Two, you know. It dates from when Hitler bombed the docks here. This house was caught in the blast and all the windows blew out and had to be replaced. So we leave the panes, whatever else we do. The glass is historic. It adds quite a bit to the value of the house.”

I ask you! He writes fantasy. He has windows that go into other dimensions. And all he can think about is how much extra money they’re worth.

Oh, I know I’m being ungrateful and horrible. They’re letting me live here. But all the same…

Nick at least has noticed about the windows. He says they give you glimpses of a great alternate universe called Bristolia. And, being in some ways as practical as his father, he has made maps of Bristolia for a role-playing game…

[3]

…a low time. I ache inside my chest about Robbie. I go into the university but I just mooch about there really. One’s supposed to get over being crossed in love. People do. It was months ago now, after all. I don’t seem to be like other people. I don’t know what I’m like. That’s the trouble with being adopted and not knowing your real parents. They have little bits of ancestry you don’t know about, and aren’t prepared for, and they cone up and hit you. You don’t know what to expect.

And my money has dwindled away to almost nothing…

[4]

Well, what do you know! I got a letter from someone called Rupert Venables. I suppose he’s a lawyer. No one but a lawyer could have that kind of name. He says a distant relative has left me a hundred quid as a legacy. Lead me to it!

Those were my first, joyous thoughts. Then Janine put the kibosh on them by asking sweetly, “What distant relative, dear? Your mother’s, your father’s, or your own?”

And Uncle Ted chipped in. “What’s this lawyer’s address? That should give you a clue.”

Practical Uncle Ted again. The man Venables writes from Weavers End, Cambridgeshire. Mum’s family comes entirely from South London. Dad’s is all Bristol. And none of them have died recently as far as we know, not even my poor little fat dad, who is still hanging on in there, out in Kent. That only leaves real, genuine relatives of my own, who could have traced me by mysterious means. I was almost excited about it until Nick said he thought it was a cruel hoax.

Nick gave his opinion an hour after the rest of us had stopped discussing it. It takes Nick that long to stop being his morning zombie self and become his normal daytime self. He got his eyes open, collected his stuff for school and picked up the letter, which he subjected to powerful scrutiny on his way out through the back door. “The address doesn’t say he’s a lawyer. The letter doesn’t say who’s left you the money. It’s a hoax,” he said. He threw the letter back at me (it missed and fell on the floor) and departed.

Hoax or not, I can use the money. I wrote to the man Venables saying so. I also suggested that he should tell me more.

Today he wrote back saying he’d come and give me the money. But he didn’t say when and he didn’t say who’d left it to me. I don’t believe a word of it. Nick is right.

[5]

…and said I had passed my driving test! I was feeling so pessimistic by then that I didn’t believe him and asked him to tell me again. And it was the same the second time round.

I wonder if test examiners aren’t used to being kissed. This one took it sort of stoically and then climbed out of the car and ran. I vaulted out. I tore off the L-plates, shot inside the car again and drove off with a zoom. I felt a bit guilty about leaving Robbie’s friend Val standing on the pavement like that, but he had only sat beside me for the hundred yards or so between his flat and the test centre. Besides, Val gives me the feel that he thinks he’s going to get me on the rebound from Robbie, and I wanted him to know different. I drove to Uncle Ted’s and screamed to a stop, double-parked outside. Nick had some sort of free day off school and I wanted him to be the first to know.

Unfortunately Janine was there too. I think she runs that clothes shop entirely by phone. Uncle Ted was in London that day, so she had come back to make sure Nick had some lunch, even though she never eats it herself. A study in Sacrificial Motherhood (actually Nick, when left to make lunch for himself, tends to drape the kitchen in several furlongs of spaghetti, and I almost see Janine’s point of view on that). She was in the kitchen with Nick when I burst in.

“So you failed again, dear. I’m so sorry,” she says. How to replace joy with anger in eight easy words.

“No, I passed,” I snapped.

“Excellent!” says Nick. “Now you can take me for a drive round Bristolia.”

“Says you!” I said. And Janine put her hand on my arm and said, “Poor Maree. She’s far too tired after all that concentrating. You mustn’t pester her, Nick.”

At that, I realised that Janine was really here to prevent me risking Nick’s neck in Dad’s car. “Tired? Who’s tired?” I said savagely. “I’m on top of the world!” I wasn’t by then. Janine had put me in a really bad mood. “You just think I’m not safe to drive Nick anywhere.”

“I didn’t say that, Maree,” she said. “But I do know I only started to learn to drive after I passed my test.”

“That’s what they all say, but it’s different for me,” I said. “I practised beforehand and ruined your fun.”

“Maree, dear,” she said. “I know you love breaking all the rules, but you really are no different from everyone else. Cars are dangerous.”

Well, we argued, Janine all sugary sweetness and light and me getting more and more inclined to bite. That’s Janine’s way. She expertly puts you in the wrong and never loses her temper. Just smiles sweetly when she’s got you hopping mad. Nick simply watched and waited. And at the crucial moment, he said, “You know she’s been driving that car for years, Mum. Maree, if you’re not going to drive me, I may as well go and see Fred Holbein.”

“No, no. I’ll drive you. I’m coming now,” I said.

“Nick, I forbid you to go,” said Janine.

He grinned at her, meltingly, and simply walked out to the car. That was it. Master Nick had decided he wanted to show me Bristolia and the womenfolk did as he wanted. Actually, I felt quite honoured, that he trusted me both to drive him and not to laugh at his Bristolia game. It put me in a much better mood. “Where to?” I said.

Nick unfolded a large, carefully coloured map. “I think we’ll start with Cliffores of the Monsters and the Castle of the Warden of the Green Wastes,” he said seriously.

So I drove him to the Zoo and then past the big red Gothic school there. Then we went round Durdham Down and on to Westbury-on-Trym and back to Redland. After that, I don’t remember where we went. Nick had different names for everywhere and colourful histories to go with every place. He told me exactly how many miles of Bristolia we’d covered for each mile of the town. I did my best to keep an intelligent interest, but Dad’s car was not behaving very well. Perhaps it believed what Nick said. After he’d told me we’d gone seven hundred miles to the Zoo, it began making grinding noises and stalling on hills. I was a bit preoccupied with making it go. But Nick went on explaining eagerly, even though some of my answers were a bit vague and sarcastic. I don’t think he noticed. I was rather touched, to tell the truth, because we used to play games like this (but on a smaller scale) when I was fourteen and Nick was eight. And I would have died rather than hurt his feelings.

We were going steeply down towards the Centre, and Nick had just told me we’d now clocked up two thousand miles of Bristolia, when he suddenly said, “Just a moment. I think we’re being followed.”

I very nearly said, “Is this part of the Game?” and I am glad I didn’t, because I was suddenly quite sure he was right. Don’t ask me how. I just knew someone was behind us, looking for us, with serious intent to find us. It was not a nice feeling. I suppose Janine must have sent someone to make sure I didn’t kill her Nick. So I said, “What do you suggest we do?”

“Keep going towards Biflumenia – I mean Bedminster,” Nick said, “and I’ll tell you what to do then.”

Traffic was pretty thick by then. It was very useful to have someone with Nick’s encyclopedic knowledge of the place to tell me what turning to take. We both dropped the Bristolia game for a tense quarter of an hour or so, while we zipped up the opposite hill across the river, came back down another way, and took the road up to the suspension bridge. The creepy feeling of someone behind us trying to find us left us on the way. Nick sat back with a sigh.

“That’s it. We lost him. Now we’re in Yonder Bristolia where most of the magic users live.”

“Yes, but I wish we weren’t in line for the suspension bridge!” I more or less moaned.

“It’s all right. I’ve got money to get across,” Nick said.

“But it’s the place I have bad dreams about!” I wailed. I really didn’t want to go there. My bad mood was back. It was thanks to Janine. She’d stripped the joy about passing my test off the underlying misery and, though I’d forgotten it a bit during the tour of exotic Bristolia, it was still there, as bad as ever.

“I was hoping I’d stopped you being so gloomy,” Nick said.

“I can’t. I’ve been crossed in love,” I said. “And there’s my dad – not to speak of the dreams.”

I suppose it’s not surprising Nick got the wrong idea of the dreams. Clifton Suspension Bridge is notorious for suicides. “You mean you dream about jumping off?” he said.

“No,” I said. “They’re weirder than that.”

“Tell the dreams,” he commanded.

So I told him, though they were something I’d never mentioned to a soul before. I almost don’t mention them to myself, apart from calling this journal Directory Thornlady just to show I know about them really. They’re too nasty. They go with a horrible, depressed, weak feeling. I’ve been having the dreams for over three years now, ever since we moved to London and Mum and Dad split up, and they make me wonder if I might be going mad. I was sure Nick would think they were mad. But there is something about driving a car that makes you confiding – like a sort of mobile analyst’s couch – and after Nick and I had shared the feeling of being followed, I felt as if we’d shared minds anyway.

In the dreams I am always at the Bristol end of the bridge, and I go up the steep path that cuts into the bank by the footpath there and find I’m on a wide moorland by moonlight (not that I ever see the moon: I just know it’s moonlight). I walk until I come to a path. Some nights I find I can dig my heels in and refuse to take that path. Then I get punished. I get lost in the dream, wandering about in beastly marsh-like places, and wake up feeling incredibly frightened and guilty. If I give in (or can’t dig my heels in) and simply follow the path, I always come to a sort of horizon, where the sky comes right down to the moor, and there is a solitary dark bush in the middle of it. That bush is an old woman.

Don’t ask me how. Nick asked me how. I couldn’t tell him. She isn’t made of twigs. She isn’t the sky showing through the bush. She isn’t even exactly in the bush. But in my dream I know that the bush is the same thing as a narrow-faced severe old woman who is probably a goddess. I don’t like her. She despises me. And she’s brought me here to tell me off.

“Don’t ever expect any sort of luck or success,” she says, “until you stop this aggressive approach to life. It’s not ladylike. A lady should sit gracefully by and let others handle things.” She always says that sort of thing, but recently she’s been on about Robbie too. At first it was the immorality of living with him, and now that seems to be over she says, “It’s degrading for a lady to go pining after a man. You won’t have any luck or worth in your life until you give up university and marry a nice normal young man.”

“And don’t tell me it’s my subconscious talking!” I said to Nick.

“It isn’t. It’s not the way you think or talk at all. It’s not you,” he said decidedly. “I think she’s a witch.”

“I call her Thornlady,” I confessed. Just then it dawned on me that Dad’s car was making incredibly heavy weather of the hill up beside the gorge. We were crawling. The engine was going punk, punk, punk. And then I looked in the mirror (which I’d forgotten to do while I told Nick about the dreams), I could see a whole line of cars snorting and toiling and crawling impatiently behind us. The road behind us between the hedges was full of blue fumes. “Oh God!” I said. “What’s wrong? We’re breaking down!”

“You could try going into another gear,” Nick suggested.

I looked down and found I was in fourth. No wonder! I slammed us down into second and we took wings. The car gave a grateful howling sound as we hurtled round the last bends and swooped along to the bridge. Nick produced a lavish handful of coins and paid the toll machine.

“It’s an omen. You may have changed my luck,” I said as we shimmied across the gorge.

“I’ve been thinking about that,” Nick answered. “We ought to break that dream. Why don’t we—”

I knew what he was going to say. We both shouted in chorus, “Do the Witchy Dance for Luck!”

I stopped the car as soon as we were across the bridge. I vaulted out. Nick unfolded out, and we both rushed to the pavement beside where the path went up. The Witchy Dance was something we had done often and often when we were kids – we were convinced then that it worked too – but we were both a bit out of practice. I got into the swing of it fairly quickly. Nick was self-conscious and he took longer. We were into the third flick, flick, flick of the fingers before he loosened up. After that we were both going like a train when people began honking and hooting horns at us.

“Take no notice,” I panted. Flick, flick, flick. “Luck, luck, luck,” we chanted. “Break that dream. Luck, luck, luck!”

The horns seemed to get louder, but I had a strong feeling the Witchy Dance was really working – Nick says he had too – so we simply went on dancing. Next thing I knew, the man in the car behind me had climbed out and marched round to the pavement in front of me.

“Go and hold your Sabbath somewhere else!” he shouted. Oh he was angry. I looked at him. I looked at his great silver car and then back at him. He was a total prat. He had a long head with smooth, smooth hair, gold-rimmed glasses, a white strappy mac and a suit, for heaven’s sake! And instead of a tie he had one of those fancy silk cravat things. Businessman, I thought. We’ve made him half a minute late for an appointment. I took a glance at Nick to see what he thought. But Nick can be a real rat. He was busy injecting acute embarrassment into every pore of himself. He stood there and he cringed, the rat! It wasn’t me, sir! She made me do it, Officer! The woman tempted me and I did eat, Lord! I could have smacked him.

So I fought my own battle as usual by pushing my glasses up my nose with one finger in order to point a truly dirty look at the prat.

Unfortunately he was a tougher nut than he looked. He held his left lens up against his left eye and gave me the dirty look right back. In spades. I was about to resort to speech then, but the prat got in first. “I am Rupert Venables,” he snaps. “I’ve been looking for you all afternoon to give you this.” And he fetches out a hundred quid and counts it into my hand.

I was too gobsmacked even to get round to asking how he knew it was me. For that, blame the other motorists. There seemed to be several hundred cars lined up going both ways by then, and they were all gooping. When they saw the money, they began to cheer. I don’t think they thought the prat was paying me to move my car, either. Oh I was FURIOUS. And Nick was overwhelmed with genuine embarrassment as soon as he heard the name and saw the money, and he was no help at all. We simply got into Dad’s car and I drove us away. Rather jerkily.

After a while I said – between my teeth – “I hope for both our sakes I never meet that prat again. Murder will be done.”

Nick said, “But the Witchy Dance has worked.”

That inflamed my wrath further. “What do you mean, you rat?”

“You got a hundred pounds with no strings attached,” he pointed out.

“They’re probably forged notes,” I said.

“What are you going to buy with them?” Nick asked.

“Oh don’t ask – I need almost everything you can name,” I said. I suppose I was mollified. I know I haven’t felt nearly so depressed since.