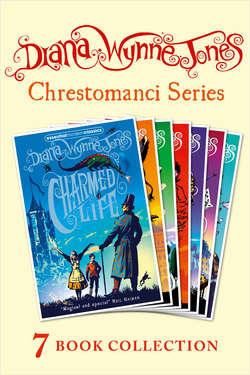

Читать книгу The Chrestomanci Series: Entire Collection Books 1-7 - Diana Wynne Jones - Страница 33

Оглавление

Benvenuto’s news caused a stampede in the Casa Montana. The older cousins raced to the Scriptorium and began packing away all the usual spells, inks and pens. The aunts fetched out the special inks for use in war-spells. The uncles staggered under reams of fresh paper and parchment. Antonio, Old Niccolo and Rinaldo went to the library and fetched the giant red volumes, with WAR stamped on their spines, while Elizabeth raced to the music room with all the children to put away the ordinary music and set out the tunes and instruments of war.

Meanwhile, Rosa, Marco and Domenico raced out into the Via Magica and came back with newspapers. Everyone at once left what they were doing and crowded into the dining room to see what the papers said.

They made a pile of people, all craning over the table. Rinaldo was standing on a chair, leaning over three aunts. Marco was underneath, craning anxiously sideways, head to head with Old Niccolo, as Rosa flipped over the pages. There were so many other people packed in and leaning over that Lucia, Paolo and Tonino were forced to squat with their chins on the table, in order to see at all.

“No, nothing,” Rosa said, flipping over the second paper.

“Wait,” said Marco. “Look at the Stop Press.”

Everyone swayed towards it, pushing Marco further sideways. Then Tonino almost knew where he had seen Marco before.

“There it is,” said Antonio.

All the bodies came upright, with their faces very serious.

“Reserve mobilised, right enough,” said Rosa. “Oh, Marco!”

“What’s the matter?” Rinaldo asked jeeringly from his chair. “Is Marco a Reservist?”

“No,” said Marco. “My – my brother got me out of it.”

Rinaldo laughed. “What a patriot!”

Marco looked up at him. “I’m a Final Reservist,” he said, “and I hope you are too. If you aren’t, it will be a pleasure to take you round to the Army Office in the Arsenal this moment.”

The two glared at one another. Once again there were shouts to Rinaldo to stop making a fool of himself. Sulkily, Rinaldo climbed down and stalked out.

“Rinaldo is a Final Reservist,” Paolo assured Marco.

“I thought he must be,” Marco said. “Look, I must go. I – I must tell my brother. Rosa, I’ll see you tomorrow if I can.”

When Tonino fell asleep that night, the room next door to him was full of people talking of war and the Angel of Caprona, with occasional digressions about Rosa’s wedding dress. Tonino’s head was so full of these things that he was quite surprised, when he went to school, not to hear them talked of there. But no one seemed to have noticed there might be a war. True, some of the teachers looked grave, but that might have been just their natural feelings at the start of a new term.

Consequently, Tonino came home that afternoon thinking that maybe things were not so bad after all. As usual, Benvenuto leapt off the water butt and sprang into his arms. Tonino was rubbing his face against Benvenuto’s nearest ragged ear, when he heard a carriage draw up behind him. Benvenuto promptly squirmed out of Tonino’s arms. Tonino, very surprised, looked round to find him trotting, gently and politely, with his tail well up, towards a tall man who was just coming in through the Casa gate.

Benvenuto stood, his brush of tail waving slightly at the tip, his hind legs canted slightly apart under his fluffy drawers, staring gravely at the tall man. Tonino thought peevishly that, from behind, Benvenuto often looked pretty silly. The man looked almost as bad. He was wearing an exceedingly expensive coat with a fur collar and a tweed travelling cap with daft earflaps. And he bowed to Benvenuto.

“Good afternoon, Benvenuto,” he said, as grave as Benvenuto himself. “I’m glad to see you so well. Yes, I’m very well thank you.”

Benvenuto advanced to rub himself round the stranger’s legs.

“No,” said the man. “I beg you. Your hairs come off.”

And Benvenuto stopped, without abating an ounce of his uncommon politeness.

By this time, Tonino was extremely resentful. This was the first time for years that Benvenuto had behaved as if anyone mattered more than Tonino. He raised his eyes accusingly to the stranger’s. He met eyes even darker than his own, which seemed to spill brilliance over the rest of the man’s smooth dark face. They gave Tonino a jolt, worse than the time the horses turned back to cardboard. He knew, beyond a shadow of doubt, that he was looking at a powerful enchanter.

“How do you do?” said the man. “No, despite your accusing glare, young man, I have never been able to understand cats – or not more than in the most general way. I wonder if you would be kind enough to translate for me what Benvenuto is saying.”

Tonino listened to Benvenuto. “He says he’s very pleased to see you again and welcome to the Casa Montana, sir.” The sir was from Benvenuto, not Tonino. Tonino was not sure he cared for strange enchanters who walked into the Casa and took up Benvenuto’s attention.

“Thank you, Benvenuto,” said the enchanter. “I’m very pleased to be back. Though, frankly, I’ve seldom had such a difficult journey. Did you know your borders with Florence and Pisa were closed?” he asked Tonino. “I had to come in by sea from Genoa in the end.”

“Did you?” Tonino said, wondering if the man thought it was his fault. “Where did you come from then?”

“Oh, England,” said the man.

Tonino warmed to that. This then could not be the enchanter the Duke had talked about. Or could he? Tonino was not sure how far away enchanters could work from.

“Makes you feel better?” asked the man.

“Mother’s English,” Tonino admitted, feeling he was giving altogether too much away.

“Ah!” said the enchanter. “Now I know who you are. You’re Antonio the Younger, aren’t you? You were a baby when I saw you last, Tonino.”

Since there is no reply to that kind of remark, Tonino was glad to see Old Niccolo hastening across the yard, followed by Aunt Francesca and Uncle Lorenzo, with Antonio and several more of the family hurrying behind them. They closed round the enchanter, leaving Tonino and Benvenuto beyond, by the gate.

“Yes, I’ve just come from the Casa Petrocchi,” Tonino heard the stranger say. To his surprise, everyone accepted it, as if it were the most natural thing for the stranger to have done – as natural as the way he took off his ridiculous English hat to Aunt Francesca.

“But you’ll stay the night with us,” said Aunt Francesca.

“If it’s not too much trouble,” the stranger said.

In the distance, as if they already knew – as they unquestionably did in a place like the Casa Montana – Aunt Maria and Aunt Anna went clambering up the gallery steps to prepare the guest room above. Aunt Gina emerged from the kitchen, held her hands up to Heaven, and dashed indoors again. Thoughtfully, Tonino gathered up Benvenuto and asked exactly who this stranger was.

Chrestomanci, of course, he was told. The most powerful enchanter in the world.

“Is he the one who’s spoiling our spells?” Tonino asked suspiciously.

Chrestomanci, he was told – impatiently, because Benvenuto evidently thought Tonino was being very stupid – is always on our side.

Tonino looked at the stranger again – or rather, at his smooth dark head sticking out from among the shorter Montanas – and understood that Chrestomanci’s coming meant there was a crisis indeed.

The stranger must have said something about him. Tonino found them all looking at him, his family smiling lovingly. He smiled back shyly.

“Oh, he’s a good boy,” said Aunt Francesca.

Then they all surged, talking, across the yard. “What makes it particularly difficult,” Tonino heard Chrestomanci saying, “is that I am, first and foremost, an employee of the British Government. And Britain is keeping out of Italian affairs. But luckily I have a fairly wide brief.”

Almost at once, Aunt Gina shot out of the kitchen again. She had cancelled the ordinary supper and started on a new one in honour of Chrestomanci. Six people were sent out at once for cakes and fruit, and two more for lettuce and cheese. Paolo, Corinna and Lucia were caught as they came in chatting from school and told to go at once to the butcher’s. But, at this point, Rinaldo erupted furiously from the Scriptorium.

“What do you mean, sending all the kids off like this!” he bawled from the gallery. “We’re up to our ears in war-spells here. I need copiers!”

Aunt Gina put her hands on her hips and bawled back at him. “And I need steak! Don’t you stand up there cheeking me, Rinaldo Montana! English people always eat steak, so steak I must have!”

“Then cut pieces off the cats!” screamed Rinaldo. “I need Corinna and Lucia up here!”

“I tell you they are going to run after me for once!” yelled Aunt Gina.

“Dear me,” said Chrestomanci, wandering into the yard. “What a very Italian scene! Can I help in any way?” He nodded and smiled from Aunt Gina to Rinaldo. Both of them smiled back, Rinaldo at his most charming.

“You would agree I need copiers, sir, wouldn’t you?” he said.

“Bah!” said Aunt Gina. “Rinaldo turns on the charm and I get left to struggle alone! As usual! All right. Because it’s war-spells, Paolo and Tonino can go for the steak. But wait while I write you a note, or you’ll come back with something no one can chew.”

“So glad to be of service,” Chrestomanci murmured, and turned away to greet Elizabeth, who came racing down from the gallery waving a sheaf of music and fell into his arms. The heads of the five little cousins Elizabeth had been teaching stared wonderingly over the gallery rail. “Elizabeth!” said Chrestomanci. “Looking younger than ever!” Tonino stared as wonderingly as his cousins. His mother was laughing and crying at once. He could not follow the torrent of English speech. “Virtue,” he heard, and “war” and, before long, the inevitable “Angel of Caprona”. He was still staring when Aunt Gina stuck her note into his hand and told him to make haste.

As they hurried to the butcher’s, Tonino said to Paolo, “I didn’t know Mother knew anyone like Chrestomanci.”

“Neither did I,” Paolo confessed. He was only a year older than Tonino, after all, and it seemed that Chrestomanci had last been in Caprona a very long time ago. “Perhaps he’s come to find the words to the Angel,” Paolo suggested. “I hope so. I don’t want Rinaldo to have to go away and fight.”

“Or Marco,” Tonino agreed. “Or Carlo or Luigi or even Domenico.”

Because of Aunt Gina’s note, the butcher treated them with great respect. “Tell her this is the last good steak she’ll see, if war is declared,” he said, and he passed them each a heavy, squashy pink armload.

They arrived back with their armfuls just as a cab set down Uncle Umberto, puffing and panting, outside the Casa gate. “I am right, Chrestomanci is here? Eh, Paolo?” Uncle Umberto asked Tonino.

Both boys nodded. It seemed easier than explaining that Paolo was Tonino.

“Good, good!” exclaimed Uncle Umberto and surged into the Casa, where he found Chrestomanci just crossing the yard. “The Angel of Caprona,” Uncle Umberto said to him eagerly. “Could you—?”

“My dear Umberto,” said Chrestomanci, shaking his hand warmly, “everyone here is asking me that. For that matter, so was everyone in the Casa Petrocchi too. And I’m afraid I know no more than you do. But I shall think about it, don’t worry.”

“If you could find just a line, to get us started,” Uncle Umberto said pleadingly.

“I will do my best!” Chrestomanci was saying, when, with a great clattering of heels, Rosa shot past. From the look on her face, she had seen Marco arriving. “I promise you that,” Chrestomanci said, as his head turned to see what Rosa was running for.

Marco came through the gate and stopped so dead, staring at Chrestomanci, that Rosa charged into him and nearly knocked him over. Marco staggered a bit, put his arms round Rosa, and went on staring at Chrestomanci. Tonino found himself holding his breath. Rinaldo was right. There was something about Marco. Chrestomanci knew it, and Marco knew he knew. From the look on Marco’s face, he expected Chrestomanci to say what it was.

Chrestomanci indeed opened his mouth to say something, but he shut it again and pursed his lips in a sort of whistle instead. Marco looked at him uncertainly.

“Oh,” said Uncle Umberto, “may I introduce—” He stopped and thought. Rosa he usually remembered, because of her fair hair, but he could not place Marco. “Corinna’s fiancé,” he suggested.

“I’m Rosa,” said Rosa. “This is Marco Andretti.”

“How do you do?” Chrestomanci said politely. Marco seemed to relax. Chrestomanci’s eyes turned to Paolo and Tonino, standing staring. “Good heavens!” he said. “Everyone here seems to live such exciting lives. What have you boys killed?”

Paolo and Tonino looked down in consternation, to find that the steak was leaking on to their shoes. Two or three cats were approaching meaningly.

Aunt Gina appeared in the kitchen doorway. “Where’s my steak?”

Paolo and Tonino sped towards her, leaving a pattering trail. “What was all that about?” Paolo panted to Tonino.

“I don’t know,” said Tonino, because he didn’t, and because he liked Marco.

Aunt Gina shortly became very sharp and passionate about the steak. The leaking trail attracted every cat in the Casa. They were underfoot in the kitchen all evening, mewing pitifully. Benvenuto was also present, at a wary distance from Aunt Gina, and he made good use of his time. Aunt Gina erupted into the yard again, trumpeting.

“Tonino! Ton-in-ooh!”

Tonino laid down his book and hurried outside. “Yes, Aunt Gina?”

“That cat of yours has stolen a whole pound of steak!” Aunt Gina trumpeted, flinging a dramatic arm skyward.

Tonino looked, and there, sure enough, Benvenuto was, crouched on the pantiles of the roof, with one paw holding down quite a large lump of meat. “Oh dear,” he said. “I don’t think I can make him give it back, Aunt Gina.”

“I don’t want it back. Look where it’s been!” screamed Aunt Gina. “Tell him from me that I shall wring his evil neck if he comes near me again!”

“My goodness, you do seem to be at the centre of everything,” Chrestomanci remarked, appearing beside Tonino in the yard. “Are you always in such demand?”

“I shall have hysterics,” declared Aunt Gina. “And no one will get any supper.”

Elizabeth and Aunt Maria and Cousins Claudia and Teresa immediately came to her assistance and led her tenderly back indoors.

“Thank the Lord!” said Chrestomanci. “I’m not sure I could stand hysterics and starvation at once. How did you know I was an enchanter, Tonino? From Benvenuto?”

“No. I just knew when I looked at you,” said Tonino.

“I see,” said Chrestomanci. “This is interesting. Most people find it impossible to tell. It makes me wonder if Old Niccolo is right, when he talks of the virtue leaving your house. Would you be able to tell another enchanter when you looked at him, do you think?”

Tonino screwed up his face and wondered. “I might. It’s the eyes. You mean, would I know the enchanter who’s spoiling our spells?”

“I think I mean that,” said Chrestomanci. “I’m beginning to believe there is someone. I’m sure, at least, that the spells on the Old Bridge were deliberately broken. Would it interfere with your plans too much, if I asked your grandfather to take you with him whenever he has to meet strangers?”

“I haven’t got any plans,” said Tonino. Then he thought, and he laughed. “I think you make jokes all the time.”

“I aim to please,” Chrestomanci said.

However, when Tonino next saw Chrestomanci, it was at supper – which was magnificent, despite Benvenuto and the hysterics – and Chrestomanci was very serious indeed. “My dear Niccolo,” he said, “my mission has to concern the misuse of magic, not the balance of power in Italy. There would be no end of trouble if I was caught trying to stop a war.”

Old Niccolo had his look of a baby about to cry. Aunt Francesca said, “We’re not asking this personally—”

“But, my dear,” said Chrestomanci, “don’t you see that I can only do something like this as a personal matter? Please ask me personally. I shan’t let the strict terms of my mission interfere with what I owe my friends.” He smiled then, and his eyes swept round everyone gathered at the great table, very affectionately. He did not seem to exclude Marco. “So,” he said, “I think my best plan for the moment is to go on to Rome. I know certain quarters there, where I can get impartial information, which should enable me to pin down this enchanter. At the moment, all we know is that he exists. If I’m lucky, I can prove whether Florence, or Siena, or Pisa is paying him – in which case, they and he can be indicted at the Court of Europe. And if, while I’m at it, I can get Rome, or Naples, to move on Caprona’s behalf, be very sure I shall do it.”

“Thank you,” said Old Niccolo.

For the rest of supper, they discussed how Chrestomanci could best get to Rome. He would have to go by sea. It seemed that the last stretch of border, between Caprona and Siena, was now closed.

Much later that night, when Paolo and Tonino were on their way to bed, they saw lights in the Scriptorium. They tiptoed along to investigate. Chrestomanci was there with Antonio, Rinaldo and Aunt Francesca, going through spells in the big red books. Everyone was speaking in mutters, but they heard Chrestomanci say, “This is a sound combination, but it’ll need new words.” And on another page, “Get Elizabeth to put this in English, as a surprise factor.” And again, “Ignore the tune. The only tune which is going to be any use to you at the moment is the Angel. He can’t block that.”

“Why just those three?” Tonino whispered.

“They’re best at making new spells,” Paolo whispered back. “We need new war-spells. It sounds as if the other enchanter knows the old ones.”

They crept to bed with an excited, urgent feeling, and neither of them found it easy to sleep.

Chrestomanci left the next morning before the children went to school. Benvenuto and Old Niccolo escorted him to the gate, one on either side, and the entire Casa gathered to wave him off. Things felt both flat and worrying once he was gone. That day, there was a great deal of talk of war at school. The teachers whispered together. Two had left, to join the Reserves. Rumours went round the classes. Someone told Tonino that war would be declared next Sunday, so that it would be a Holy War. Someone else told Paolo that all the Reserves had been issued with two left boots, so that they would not be able to fight. There was no truth in these things. It was just that everyone now knew that war was coming.

The boys hurried home, anxious for some real news. As usual, Benvenuto leapt off his water butt. While Tonino was enjoying Benvenuto’s undivided attention again, Elizabeth called from the gallery, “Tonino! Someone’s sent you a parcel.”

Tonino and Benvenuto sprang for the gallery stairs, highly excited. Tonino had never had a parcel before. But before he got anywhere near it, he was seized on by Aunt Maria, Rosa and Uncle Lorenzo. They seized on all the children who could write and hurried them to the dining room. This had been set up as another Scriptorium. By each chair was a special pen, a bottle of red war-ink and a pile of strips of paper. There the children were kept busy fully two hours, copying the same war-charm, again and again. Tonino had never been so frustrated in his life. He did not even know what shape his parcel was. He was not the only one to feel frustrated.

“Oh, why?” complained Lucia, Paolo and young Cousin Lena.

“I know,” said Aunt Maria. “Like school again. Start writing.”

“It’s exploiting children, that’s what we’re doing,” Rosa said cheerfully. “There are probably laws against it, so do complain.”

“Don’t worry, I will,” said Lucia. “I am doing.”

“As long as you write while you grumble,” said Rosa.

“It’s a new spell-scrip for the Army,” Uncle Lorenzo explained. “It’s very urgent.”

“It’s hard. It’s all new words,” Paolo grumbled.

“Your father made it last night,” said Aunt Maria. “Get writing. We’ll be watching for mistakes.”

When finally, stiff-necked and with red splodges on their fingers, they were let out into the yard, Tonino discovered that he had barely time to unwrap the parcel before supper. Supper was early that night, so that the elder Montanas could put in another shift on the army-spells before bedtime.

“It’s worse than working on the Old Bridge,” said Lucia. “What’s that, Tonino? Who sent it?”

The parcel was promisingly book-shaped. It bore the stamp and the arms of the University of Caprona. This was the only indication Tonino had that Uncle Umberto had sent it, for, when he wrenched off the thick brown paper, there was no letter, not even a card. There was only a new shiny book. Tonino’s face beamed. At least Uncle Umberto knew this much about him. He turned the book lovingly over. It was called The Boy Who Saved His Country, and the cover was the same shiny, pimpled red leather as the great volumes of war-spells.

“Is Uncle Umberto trying to give you a hint, or something?” Paolo asked, amused. He and Lucia and Corinna leant over Tonino while he flipped through the pages. There were pictures, to Tonino’s delight. Soldiers rode horses, soldiers rode machines; a boy hung from a rope and scrambled up the frowning wall of a fortress; and, most exciting of all, a boy stood on a rock with a flag, confronting a whole troop of ferocious-looking dragoons. Sighing with anticipation, Tonino turned to Chapter One: How Giorgio Uncovered an Enemy Plot.

“Supper!” howled Aunt Gina from the yard. “Oh I shall go mad! Nobody attends to me!”

Tonino was forced to shut the lovely book again and hurry down to the dining room. He watched Aunt Gina anxiously as she doled out minestrone. She looked so hectic that he was convinced Benvenuto must have been at work in the kitchen again.

“It’s all right,” Rosa said. “It’s just she thought she’d got a line from the Angel of Caprona. Then the soup boiled over and she forgot it again.”

Aunt Gina was distinctly tearful. “With so much to do, my memory is like a sieve,” she kept saying. “Now I’ve let you all down.”

“Of course you haven’t, Gina my dear,” said Old Niccolo. “This is nothing to worry about. It will come back to you.”

“But I can’t even remember what language it was in!” wailed Aunt Gina.

Everyone tried to console her. They sprinkled grated cheese on their soup and slurped it with special relish, to show Aunt Gina how much they appreciated her, but Aunt Gina continued to sniff and accuse herself. Then Rinaldo thought of pointing out that she had got further than anyone else in the Casa Montana. “None of the rest of us has any of the Angel of Caprona to forget,” he said, giving Aunt Gina his best smile.

“Bah!” said Aunt Gina. “Turning on the charm, Rinaldo Montana!” But she seemed a good deal more cheerful after that.

Tonino was glad Benvenuto had nothing to do with it this time. He looked round for Benvenuto. Benvenuto usually took up a good position for stealing scraps, near the serving table. But tonight he was nowhere to be seen. Nor, for that matter, was Marco.

“Where’s Marco?” Paolo asked Rosa.

Rosa smiled. She seemed quite cheerful about it. “He has to help his brother,” she said, “with fortifications.”

That brought home to Paolo and Tonino the fact that there was going to be a war. They looked at one another nervously. Neither of them was quite sure whether you behaved in the usual way in wartime, or not. Tonino’s mind shot to his beautiful new book, The Boy Who Saved His Country. He slurped the title through his mind, just as he was slurping his soup. Had Uncle Umberto meant to say to him, find the words to the Angel of Caprona and save your country, Tonino? It would indeed be the most marvellous thing if he, Tonino Montana, could find the words and save his country. He could hardly wait to see how the boy in the book had done it.

As soon as supper was over, he sprang up, ready to dash off and start reading. And once again he was prevented. This time it was because the children were told to wash up supper. Tonino groaned. And, again, he was not the only one.

“It isn’t fair!” Corinna said passionately. “We slave all afternoon at spells, and we slave all evening at washing-up! I know there’s going to be a war, but I still have to do my exams. How am I ever going to do my homework?” The way she flung out an impassioned arm made Paolo and Tonino think that Aunt Gina’s manner must be catching.

Rather unexpectedly, Lucia sympathised with Corinna. “I think you’re too old to be one of us children,” she said. “Why don’t you go away and do your homework and let me organise the kids?”

Corinna looked at her uncertainly. “What about your homework?”

“I’ve not got much. I’m not aiming for the University like you,” Lucia said kindly. “Run along.” And she pushed Corinna out of the dining room. As soon as the door was shut, she turned briskly to the other children. “Come on. What are you lot standing gooping for? Everyone take a pile of plates to the kitchen. Quick march, Tonino. Move, Lena and Bernardo. Paolo, you take the big bowls.”

With Lucia standing over them like a sergeant major, Tonino had no chance to slip away. He trudged to the kitchen with everyone else, where, to his surprise, Lucia ordered everyone to lay the plates and cutlery out in rows on the floor. Then she made them stand in a row themselves, facing the rows of greasy dishes.

Lucia was very pleased with herself. “Now,” she said, “this is something I’ve always wanted to try. This is washing-up-made-easy, by Lucia Montana’s patent method. I’ll tell you the words. They go to the Angel of Caprona. And you’re all to sing after me—”

“Are you sure we should?” asked Lena, who was a very law-abiding cousin.

Lucia gave her a look of scalding contempt. “If some people,” she remarked to the whitewashed beams of the ceiling, “don’t know true intelligence when they see it, they are quite at liberty to go and live with the Petrocchis.”

“I only asked,” Lena said, crushed.

“Well, don’t,” said Lucia. “This is the spell…”

Shortly, they were all singing lustily:

“Angel, clean our knives and dishes,

Clean our spoons and salad-bowls,

Wash our saucepans, hear our wishes,

Angel, make our forks quite clean.”

At first, nothing seemed to happen. Then it became clear that the orange grease was certainly slowly clearing from the plates. Then the lengths of spaghetti stuck to the bottom of the largest saucepan started unwinding and wriggling like worms. Up over the edge of the saucepan they wriggled, and over the stone floor, to ooze themselves into the waste-cans. The orange grease and the salad oil travelled after them, in rivulets. And the singing faltered a little, as people broke off to laugh.

“Sing, sing!” shouted Lucia. So they sang.

Unfortunately for Lucia, the noise penetrated to the Scriptorium. The plates were still pale pink and rather greasy, and the last of the spaghetti was still wriggling across the floor, when Elizabeth and Aunt Maria burst into the kitchen.

“Lucia!” said Elizabeth.

“You irreligious brats!” said Aunt Maria.

“I don’t see what’s so wrong,” said Lucia.

“She doesn’t see – Elizabeth, words fail!” said Aunt Maria. “How can I have taught her so little and so badly? Lucia, a spell is not instead of a thing. It is only to help that thing. And on top of that, you go and use the Angel of Caprona, as if it was any old tune, and not the most powerful song in all Italy! I – I could box your ears, Lucia!”

“So could I,” said Elizabeth. “Don’t you understand we need all our virtue – the whole combined strength of the Casa Montana – to put into the war-charms? And here you go frittering it away in the kitchen!”

“Put those plates in the sink, Paolo,” ordered Aunt Maria. “Tonino, pick up those saucepans. The rest of you pick up the cutlery. And now you’ll wash them properly.”

Very chastened, everyone obeyed. Lucia was angry as well as chastened. When Lena whispered, “I told you so!” Lucia broke a plate and jumped on the pieces.

“Lucia!” snapped Aunt Maria, glaring at her. It was the first time any of the children had seen her look likely to slap someone.

“Well, how was I to know?” Lucia stormed. “Nobody ever explained – nobody told me spells were like that!”

“Yes, but you knew perfectly well you were doing something you shouldn’t,” Elizabeth told her, “even if you didn’t know why. The rest of you, stop sniggering. Lena, you can learn from this too.”

All through doing the washing-up properly – which took nearly an hour – Tonino was saying to himself, “And then I can read my book at last.”

When it was finally done, he sped out into the yard. And there was Old Niccolo hurrying down the steps to meet him in the dark.

“Tonino, may I have Benvenuto for a while, please?”

But Benvenuto was still not to be found. Tonino began to think he would die of book-frustration. All the children joined in hunting and calling, but there was still no Benvenuto. Soon, most of the grown-ups were looking for him too, and still Benvenuto did not appear. Antonio was so exasperated that he seized Tonino’s arm and shook him.

“It’s too bad, Tonino! You must have known we’d need Benvenuto. Why did you let him go?”

“I didn’t! You know what Benvenuto’s like!” Tonino protested, equally exasperated.

“Now, now, now,” said Old Niccolo, taking each of them by a shoulder. “It is quite plain by now that Benvenuto is on the other side of town, making vile noises on a roof somewhere. All we can do is hope someone empties a jug of water on him soon. It’s not Tonino’s fault, Antonio.”

Antonio let go Tonino’s arm and rubbed both hands on his face. He looked very tired. “I’m sorry, Tonino,” he said. “Forgive me. Let us know as soon as Benvenuto comes back, won’t you?”

He and Old Niccolo hurried back to the Scriptorium. As they passed under the light, their faces were stiff with worry. “I don’t think I like war, Tonino,” Paolo said. “Let’s go and play table-tennis in the dining room.”

“I’m going to read my book,” Tonino said firmly. He thought he would get like Aunt Gina if anything else happened to stop him.