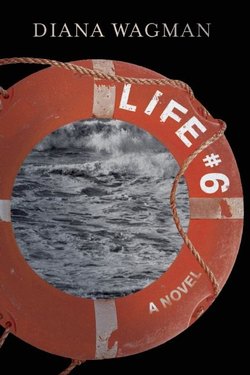

Читать книгу Life #6 - Diana Wagman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4.

All five of us were on deck when we motored out of the harbor. It was after eleven but the two-hour delay had given the clouds a chance to lift. The November sun was shining the best it could. Nathan sang and Luc joined in, “Sailing, sailing, over the bounding main!” I waved goodbye to the wharf. Ours was the only sailboat going out. The others were tied up at the docks, their sails rolled and stored, their cushions taken home, everything battened down and tightened up for winter. I waved to the Harbormaster who had come out on the widow’s walk to watch us go. He didn’t wave back. Everyone in town thought we were crazy for going, but I looked at Joren calmly rolling a cigarette as he sat behind the helm and Luc talking happily with Nathan and I thought, this is it—my adventurous life is beginning. Luc and I would stay with the boat in Bermuda, be island sailors and live in our bathing suits. My thighs would not embarrass me, my too white skin would turn brown. Did you hear about Fiona? I could hear my high school friends ask each other. We thought she was a loser, but she lives on a sailboat in the South Seas. I wasn’t sure Bermuda was in the South Seas, but it sounded good.

I felt a drop of rain. Then another. And another. Dark clouds rolled across the sky. Joren turned the engine off. The mainsail flapped and shook as he steered us directly into the wind.

“This is no-go,” Nathan said. “Come on, Captain.”

Joren looked confused.

“We’ll end up in irons!” Someplace Nathan obviously didn’t want to be. He pushed Joren out of the way and turned the wheel right—starboard. The boat creaked as it slowly made the turn, but then the wind caught the sail and suddenly we were going.

“This is it!” Nathan hollered. “Reaching. Yes!” He turned to Joren. “Even an imbecile can sail a boat with wind like this.”

We hurtled through the water. The rain came down. The boat leaned away from the wind. I grabbed the cockpit railing. The speed was okay, the leaning was not. Doug’s teeth were clamped together. The knuckles of Joren’s remaining fingers were white around a metal cleat. Only Luc, and Nathan—of course—were having fun.

I wanted to say wait. Slow down. I managed, “Why are we leaning?”

Nathan yelled over his shoulder. “Heeling. The wind. This is how we move.”

“Why don’t we fall over?” This could not go on for the whole trip. My strong thighs were already tired and my feet hurt from my toes gripping inside my sneakers.

Nathan just shook his head. Too much to explain.

I closed my eyes and sent two wishes aloft: one, to be brave and two, to get there quickly. I opened my eyes and saw that Joren’s eyes were closed. His lips moved and it worried me that he was also wishing, maybe even praying. But Nathan was calm and Luc was smiling and it was raining but not hard and the open ocean stretched out in front of us in grays and frothy creamy lace and I could see how sailors thought it beautiful.

The wind and rain in my face were cold. I turned back to look at Newport. And I gasped. Newport was gone. The shore had disappeared. There was nothing but water in every direction. No land, no other boats. No place to get off. The sea was not beautiful, only endless, eternal, and alien. I gulped, sucked at the air. I could not breathe. I opened my mouth wide, pushed against my chest with both hands. I was drowning in the open air. The boat was very small and very full. There was nowhere I could go, no place to be alone, no room to walk without stepping on someone. I wanted off, right away. I turned to Luc, but he was talking to Nathan. I looked at Doug, but his face was tucked into his enormous coat. Stop, I wanted to say. Turn around and take me back. Nathan was doing something with a rope. He pulled the sail tighter. The boat heeled more sharply. I crouched in the cockpit, holding on with both hands. Luc hollered in joy. Then, over the sound of the waves and wind, I heard a crash. Thirty minutes into our voyage and the fruit bowl with the mermaids—my favorite purchase—was the first thing to break.

From: Fionartlvr@hotmail.com

To: Luckyman@kazaroswellness.org

Sent: October 27, 2009

Dear Luc:

Well. It’s raining here—very unusual for southern California. The only rain boots I own are hand me downs from my twenty-year-old son. Yes, I have an almost grown up son. He is older than I was when we went to sea on the Bleiz A Mor.

Thirty years since we were in Newport. I wonder what it’s like now. I wish I could stand on that dock and look out at the Atlantic Ocean.

Do you remember the boat? The trip? Nathan Carmichael? Do you ever think about it?

Io

I had driven home in the rain, and sat in my driveway watching the rivulets and puddles forming in my front yard. Eventually I got out of the car. Looking up at the spitting sky, my wet face reminded me of being on that boat. Of sitting next to Luc on deck as we went out to sea, his arm around me, huddled into his chest, trying to be brave and happy before everything went so horribly wrong. Twenty-six years had passed since I had seen Luc or even heard about him. Last time, half a lifetime ago, he was strung out, an incoherent junkie. Right after that, Lola told me never to call or contact either of them again. I wasn’t helping and he was on his own path, she said. I could see only one direction that path was going, only one place it would end. That’s why I had never looked him up before. Twenty-six years and the Internet, I could have done a search for him on my phone for chrissakes, and I never did. The last time I saw him he was fading away, more ephemeral and more beautiful and more fucked up than ever before. Maybe I thought by not knowing I could keep him alive.

On the front porch, watching the rain drip from the eaves, I took out my phone and listened again to the message from Dr. Carolyn. It hadn’t changed. I went inside the house where I’d lived for more than fifteen years. It didn’t look the same. I didn’t recognize the furnishings. Was that chair always so green? When did I buy a throw pillow with a bird on it. A bird? Really? And everything was so dirty. The gray drizzly light through the dining room window revealed dust bunnies in the corners, dog hair on the rug, crumbs on the table, and a layer of grime over everything. I sat down on the couch and Lulu, our old black and white mutt, trotted over to me. She was antsy, anxious to go out, but I held her sides and buried my face in her ruff. She wagged her tail and whined, confused by me and the unfamiliar weather.

I wanted a puppy. Harry would get a job soon, Jack was across town at school, and a little cuddly pup would be just what the doctor ordered. I went to the door and picked up my car keys. I thought I’d go to the pound that minute. I couldn’t wait another second. I opened the front door and then I put my keys down. I was going to die. Who would take care of a puppy?

I went to the kitchen. Harry had left a dirty mug on the counter, dregs of milky tea in the bottom. A banana peel splayed next to it—empty, abandoned. I turned away and opened my computer. I intended to look up cancer information. I found myself thinking of Luc instead. My fingers trembled as I typed “Luc Kazaros” into Google. I tried to push away the memories of his hands on my body and his tongue on my skin, his grin, his quick steps and light touch, the boy he had been and the girl I was.

“Dance with me,” he said the day we met. He grabbed me around the waist before I could answer and pulled me into a polka. “C’mon, c’mon, c’mon.” I didn’t know then it would become his constant refrain with me.

A long list came up, filling my computer screen. I held my breath, preparing for an obituary or a news article ending with him going to jail. But he’d gone to graduate school. He was a psychologist with his own Kazaros Wellness Clinic in Orlando, Florida. Body therapy. Dream work. Reiki. Same old non-traditional guy, but with a PhD after his name. Hard to believe he wasn’t choreographing or at least teaching dance. And Orlando was where his parents lived. He had loved New York. All those years ago when I left the city and wanted him to come with me, he was adamant he would never live anywhere else.

I wrote my email to him—upbeat, noncommittal—and hit “send” before I lost my nerve.

The dog ran to the front door. Harry was coming up the walk. I put the computer to sleep. I didn’t know where Harry had been. He was dressed up in khaki pants and a button down. The pants were a little tight after all his time on the couch. His strong, stocky body had always pleased me, made me feel lighter and more graceful. In our early days he often picked me up and carried me. His face was kind and intelligent. He was such a nice guy, a good guy, a sweetheart. It didn’t seem fair to tell him I had just emailed my old boyfriend. Or to tell him I had cancer.

“Where’ve you been?” I said.

“I had an interview.” He smiled a little. He was standing straighter, his chest forward, chin up.

“Where?”

“A trade journal. The Hemp Growers Association.”

“Seriously? You never even got high.”

His smile disappeared. His eyes went small. “Aren’t you happy for me?”

I felt like a jerk. “Sorry. I know hemp isn’t just pot. It’s fantastic. Really.”

He gave a small, tired sigh. So many interviews, so many rejections. Harry had a graduate degree in International Studies from Yale. He’d written stories on the President, members of Congress, the environmental impact of plastics in Mumbai. He had spent three months embedded with the Marines in Iraq. Boys, he said, no older than our son, Jack. There’d been some awful fight, an explosion, and most of the boys had died. Harry had pulled two of them from the burning Humvee. President Bush sent him a letter of commendation, but he threw it away. And here he was, excited about hemp.

“You know,” he was saying, “these smaller, targeted journals are really the way of the future. Pretty soon no one will read a general newspaper, only articles—online probably—about their specific interests.”

“Is it full time?”

“You’re not even listening to me.”

“I am. I am.”

“All you care about is the money. Isn’t that what you were going to ask me next? How much does it pay?” He shook his head. “Jesus. I haven’t even got the job yet.”

“I didn’t ask.”

“Money, money, money. That’s all it is with you.” His face was red. His belly jiggled as he shouted at me. “Fucking money isn’t everything.”

I fled to the bedroom. He wasn’t making any sense. I didn’t care about money. Not like he did. I’d grown up with my mother counting pennies to make the rent. We had spent more than one night in the dark because there was no money for the electric bill, eating pancakes for dinner made with one egg instead of two. Then some new man would come along and we’d be fine. We were always fine. Harry and I would be fine too. We were educated people. We had gone to college and done everything right. Of course we’d be okay. Yes, next month we would have to cash out our 401k, but I was looking for full time work and had asked my boss at the Getty for more days. I pushed the thought of cancer away. Plenty of people with cancer worked full time.

The telephone rang and Harry answered it. Through the bedroom door, I could hear his voice, but not what he was saying. I crossed my fingers, hoping it was the hemp journal offering him the job. I turned on the TV to my favorite, The Weather Channel.

A stalled front over the Midwest set the stage for severe thunderstorm complexes from Nebraska to the Ohio Valley.

Shots of Iowans scurrying along the Des Moines streets under their umbrellas, frowning up at the sky as if it had betrayed them. I pulled a pillow into my lap, ran my fingernails along the seams, back and forth, back and forth.

Some of these storms were significant with damaging wind gusts the main threat. Heavy rainfall is also an ongoing concern. Downpours of one to three inches or more in a very short time caused dangerous flash flooding. Two people were found dead in a ravine where they were apparently fishing, while Marilyn Hobart was trapped on top of her car for almost five hours.

I watched the footage of Marilyn Hobart being lifted to safety by helicopter. Harry opened the bedroom door. I could see on his face he was sorry. I was too.

“Look at this,” I said. “Flash flood. This woman was stuck on top of her car for five hours.”

“Jack’s coming over.”

“That’s a nice surprise.”

Harry sat down beside me on the bed. I leaned against my husband of twenty-two years and put my hand on his back. It had been more than a year since we had made love. At first, I admit I didn’t miss it. But eventually I began to crave his touch, his full weight on me. I would snuggle against him in bed and he would turn over and tell me to go to sleep. Once he yelled at me to leave him alone, stop pawing at him. Since Jack had gone back to school, Harry had been sleeping in his room.

I opened my mouth to tell Harry my bad news. He stood up. “Harry.” I reached for him. He stepped away from me and opened the closet door to change out of his interview clothes.

“I’ll make dinner.” I slipped past him to the kitchen.

I made fresh pesto, Jack’s favorite. Harry opened a bottle of wine and clinked my glass in a toast to hemp. The rain was coming down even harder, and I was relieved when I heard Jack pull up.

I went out on the front porch to greet him. He jogged up the driveway carrying a bag of laundry over his head. Inside, he gave his one-sided grin, dropped his bag and hugged me. I could smell the rain on him and his boy scent of French fries and minty deodorant. It was impossible to tell him I had cancer. I didn’t want him to be one of those brave kids with a sick parent and a haunted look, coping and grown up before his time. He pushed his dark blond hair off his smooth forehead. Handsome as the day is long. Another of my mother’s phrases. And this day had been long and I was so glad to see him I almost cried.

He wiped his wet hands on his jeans. “Has it ever rained this much before?”

“Global climate change,” Harry said from the couch. “People need to take it seriously.”

I nodded. “After dinner we’re building an ark.”

Jack followed me into the kitchen and I poured him a glass of wine. He was such a good kid, so much better than his mother. By the time I was his age I had snorted plenty of coke, dropped many tabs of acid, spent whole days stoned. Wake and bake had been my high school motto. Jack grimaced after his first sip, so I poured the rest of his glass into mine. I made a salad and we talked about school and his music.

“It is really a big storm,” he said. For a moment he looked six-years-old, frightened by the wind and rumbling thunder.

“Maybe you should spend the night.”

“Yeah right, Mom.”

The chimes on the front porch clanged. I smelled the rain, felt the tremble of our old house, and remembered the screech of the fiberglass boat straining in the storm. Once again I was at sea.

Harry started shouting from the living room. He was obsessed with the Najibullah Zazi arrest. The press said Zazi was another Islamic terrorist who wanted to blow up America. Harry didn’t believe it. He thought the government was framing him, making Zazi a scapegoat so Homeland Security would look good. Harry thought our country had gone to hell.

“Listen to this!” he yelled to me, to us. “They’re calling him the Beauty Parlor Bomber. Catchy, don’t you think?”

Jack went in to watch with him.

I drank the rest of my wine. I put the big pasta pot in the sink and turned on the faucet. The water came out, clear and clean and exquisite, as if I’d never seen water before. The pot filled and I watched the water run over the sides, fascinated by the waterfalls and eddies in the sink. I plunged my hands in and shivered from the cold.

What was I doing? I emptied the pot and dried my hands. Filled the pot again, put it on the stove and turned on the flame. Concentrate, I told myself. Stay with the program.

My computer dinged from the corner where I’d stuck it. I opened it and everything—water, pasta, cancer, even Jack—fell away:

Io (you still use that name?) Io, Io—

Jesus, I’ve missed you. I can’t help it, but your name falls from my lips at all hours. At work, at home, with my kids. I married Beth. Remember her? She helped me when I needed it. I have three kids: two girls, Lily, from my first marriage, and Sophie, and a boy, Jack. He is spoiled rotten by his sister, just like me. Are you really thinking about Newport? Can you meet me there? When, when, when? Tell me you can go to Newport on Thursday, November 5th and go back Sunday. Tell me you can do that. Can you? Please. Can I see you?

I wrote back immediately, before I could think:

My son’s name is also Jack. Okay. Thursday to Sunday. I’ll be there.

Jack shouted from the other room, “You have no idea what I’m doing!” Harry yelled back. They were fighting. Again. I had left them alone too long. Since Harry had lost his job he was angry with Jack all the time. Jack wasn’t working hard enough. Music was a ludicrous major. He needed to think about his future.

“That’s the way things are done!” Harry roared.

“Not for me!” Jack banged the coffee table in frustration.

I came into the living room. “Dinner’s ready.”

“Fiona, please.”

“I’m not hungry,” Jack said. “I have to go.”

“I saw on TV,” I began, “about a flash flood. A woman who needed to be rescued from the roof of her car.”

“Mom.”

Harry rolled his eyes. “We’re talking about something else.”

“You’re shouting.”

“I AM NOT!”

Jack gave some excuse and escaped. I ran after him through the drizzle to his car with a Tupperware container of pasta and pesto.

“Sorry, Mom.”

“Your dad just needs a job.” I leaned in his open window to give him a kiss. I kept my hand on the door. I didn’t want him to go. I didn’t want to go back inside. Take me, I almost whispered. “Drive carefully,” I said. “Are your tires okay? Do your wipers work?”

“Bye, Mom. Tell Dad I love him.”

“Even if he is an asshole.”

He laughed and drove away and before he was out of sight I missed him. I missed the smaller him, the lap-sitter snuggly boy he had been. I missed the ten-year-old; I missed the pimply pre-teen; the new driver; the high school senior. I missed them all. They were gone. And this Jack, this young man, was going, going.

We experience so many deaths in our lifetime. Not just the actual demise of people or animals. Not just the end of a job or relationship or the departure of our children into their own lives. We suffer personal deaths, little bits of ourselves that pass away. Our hair and our memory. Our quick step. Our joints betray us. Our eyes give out. Our libido fades. But humans, we mourn, but we don’t stop. We get facelifts and take exercise classes and eat kale and buy all kinds of products to keep us going, even if we’re not exactly whole anymore. Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable says a cat has nine lives because a cat is “more tenacious of life than any other animal.” Really? I think humans win. Humans hang on. Humans take the pills, do the tests, have the twelve-hour surgery, and finally demand to subsist for years attached to tubes and machines, unable to walk or wave or even swallow. Talk about tenacity.

On the boat, Doug told me he knew people who should have died and didn’t. He used himself as an example and said he believed each of us is given many lives to live. How many? I asked him. His wool hat glittered with raindrops every time the strobe light flashed. The sea moved up and down behind him, up and down. If cats have nine lives, I asked him, how many do I have? How many have I used up?