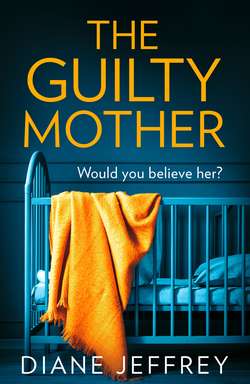

Читать книгу Diane Jeffrey Book 3 - Diane Jeffrey, Diane Jeffrey - Страница 12

Chapter 1 Jonathan April 2018

ОглавлениеI watch helplessly as Noah hits Alfie for the second time.

‘Give it back!’ Alfie wails.

‘Stop it, you two,’ I snap, giving them a stern stare in the rear-view mirror. They haven’t seen me, and they might as well not have heard me either. I shift my gaze to the dashboard clock. They’re going to be late for school. Again. That’s the third time this week. And it’s only Wednesday.

Switching off the radio with a sigh, I glance at them in the mirror again. Alfie tries to hit Noah back, but Noah dodges his younger brother’s fist and then laughs at him, which upsets Alfie even more. He starts to cry.

‘Noah, you’re three years older than him,’ I scold. ‘Try and act your age.’ I wince. Sometimes my mouth opens and my parents’ words tumble out. ‘Please give Alfie back his spinner.’ Now I’m pleading. That sounds more like me. Life would be easier if I gave in to Noah’s demands and allowed him to sit in the front.

As I pull up at the bus stop a few feet away from the entrance to Kingswood Secondary School, Noah hands over the toy. Then he leaps out of the car and strolls away without so much as a goodbye.

I drive around the corner to the junior school. Stopping on the yellow zigzag lines, I flick my hazards on. Alfie and I get out of the car.

‘I’ll come in and apologise to your teacher,’ I say, grabbing Alfie’s bag from the passenger seat.

‘I can go in by myself,’ he says, slamming his door shut and peering up at me through his mother’s chocolate eyes. Invisible fingers pinch my heart.

‘I know you can, but we’re late and—’

‘Dads never come in.’ The way he says it implies it’s only mums who do, and now the hand gives my heart a hard squeeze. ‘Anyway, she knows you have a problem with punctuality. She’s used to it,’ he adds. ‘Plus if you park there …’ he points an accusatory finger at my Ford Focus ‘… you’ll get another fine.’

I can’t believe I’m hearing my nine-year-old son correctly. I ruffle his hair and hand over his bag before getting back in behind the wheel. A wave of sadness breaks over me as he turns away. He reminds me so much of his mother. Too much. Putting the key into the ignition, I watch him sprint through the school gates.

Fifteen minutes later and fifteen minutes late, I slide into the chair at my workstation next to Kelly, our junior reporter, who grins at me. I smile back, pretending not to notice as she hastily closes the Facebook window on her laptop.

A drill starts somewhere in the office so I take my earplugs out of their box and push them into my ears. Now I’ve been officially made chief reporter, I’m to have my own private office. As far as I can see, this is about the only perk to a promotion that amounts to a token increase in salary and a large increase in my workload. At the moment, however, everything is being refurbished to our new editor’s requirements. The need to get rid of the open-plan office space for our reporters is about the only thing we’ve agreed on since she took over six months ago.

The idea now is to put up a combination of Perspex and plywood walls to create cubicles with the aim of reducing not only noise levels in the workplace but also the stress levels of the journalists working there. In addition, it’s supposed to boost productivity at The Redcliffe Gazette – or The Redcliffe Rag as we call it, although I imagine in Kelly’s case she’ll be able to spend more time on social media without feeling like she’s under surveillance.

I’ve booted up my laptop, replied to a few emails and fetched myself some coffee before Kelly speaks to me.

‘What was that?’ I pull out one of my earplugs and try not to stare at the diamond stud in Kelly’s otherwise perfect button nose.

‘Just remembered. Saunders wanted to see you in the Aquarium as soon as you got in.’

‘Thanks,’ I mutter.

‘You’re welcome.’ Not picking up on my sarcastic tone, or maybe choosing to ignore it, she turns back to her computer screen.

‘Did she say what she wanted?’

Kelly shakes her blond bobbed head. Claire doesn’t usually call me into her office first thing in the morning. This can’t be good.

I raise my hand to knock on the door of our news editor’s glass-walled office, but she has already noticed me, and waves her hand for me to come in. She’s standing at the open window, blithely flouting the law by lighting up a Marlboro. My favourite brand. I gave up years ago, just before Noah was born, in fact, but every time I come in here, the old habit beckons to me and I feel like a cigarette.

Between puffs, she purses her thin lips and flutters her long eyelashes at me. It’s a look I know well. It means this isn’t open to discussion. Nope, I’m not going to like this.

Suppressing a sigh and adopting a military at-ease stance, I give a fairly good impression of a patient man while I wait for Claire to finish her cigarette. Eventually she stubs it out in an ashtray on the windowsill, and closes the window.

A petite, slim woman, Claire has a long, straight nose and an angular jawline, high cheekbones and hollow cheeks. Her cropped hair is dyed jet black. A pencil lives almost permanently behind her right ear, but I’ve never seen her use it. She has striking green eyes, which bore into me now.

She gets straight to the point. ‘I’m sure you’ve heard about the Slade woman’s appeal application,’ she says.

‘Yes, of course.’ It doesn’t sound very convincing, even to me. I worked late last night, updating an online story, so I didn’t watch the news, and this morning I turned off the radio in the car because the boys were fighting. I have no idea what Claire is talking about, but I’m not about to admit that.

‘I’d like you to look into it,’ she continues, arching an eyebrow at me. She’s not fooled. ‘All we know is that new evidence has come to light. Find out what’s going on. Interview family members. There’s a front-page news story here, I’m sure of it. I don’t need to tell you that a good article could attract digital display ads for our online paper, too. I want to run this scoop for The Gazette before The Post even gets wind of it.’

The Rag is only a small-market weekly newspaper. We’re understaffed, underpaid and overworked and we’re all multi-tasking. But Claire is very ambitious and has set her sights on having a bigger circulation than The Bristol Post one day and a larger online readership than their website, Bristol Live. Personally, I doubt that will happen any time soon, if ever.

‘I’m thinking a big front-page splash,’ Claire continues, spreading her arms in an expansive gesture. ‘I’m thinking exclusive interviews with her son and her husband. I’m thinking never-before-seen baby photos …’

Claire continues in this vein and I tune out. I’m thinking pizza and Paddington 2 with Noah and Archie after this evening’s homework. Then I groan inwardly, remembering I’ve got to go to a Chekhov play tonight to write a review for our monthly print magazine. I can hear the rise and fall of Claire’s voice, but it sounds muffled, as if I’ve put my earplugs back in. Lost in my thoughts, I nod and shake my head in what sounds like the right places and grunt periodically.

I snap out of my reverie when Claire barks, ‘Understood?’

‘Yep.’

‘Good.’

I still haven’t a clue what she’s on about. Slade. It’s a very common surname in the Bristol area, but it does ring a bell. An alarm bell. A distant, dormant memory stirs lazily in a corner of my mind. I can’t quite bring it to the surface. Something unsavoury, though, I’m certain of that. A knot forms in my stomach. Although I can’t recall who this woman is, a voice in my head is warning me not to rouse this memory. Some strange sixth sense is telling me to stay away.

‘We’re done.’ I’m being dismissed. ‘Oh, and Jonathan? Send Kelly in here, will you? How that girl got an English degree with grammar as terrifying as hers is beyond me.’ Claire pauses and tucks a non-existent strand of hair behind her ear, knocking the pencil to the floor. I find myself wondering if she used to have long hair as I pick it up for her.

‘Yes, of course.’ I leave the office. Poor kid. If there’s anything sharper than Claire’s features, it’s her tongue, and I think Kelly is about to be on the receiving end.

‘It’s your turn,’ I say to Kelly, slipping back into my swivel chair. I follow Kelly into the Aquarium with my eyes and then I watch Claire through the glass of her office as she paces the floor, shakes her head in an exaggerated manner, wags her finger, and finally stands still with her hands on her hips. I can’t hear what she’s saying from here, but everything in her body language indicates she’s giving our trainee reporter a severe tongue-lashing. Kelly has her back to me, but I can tell from the way she’s hanging her head and hunching her shoulders that she’s not taking this well. Claire looks up and catches me staring, so I swivel my chair round to face my laptop.

I allow myself to gaze at the wallpaper image on my screen for several seconds. It’s a holiday snap, taken nearly four years ago. Alfie and Noah, all smiles, are sitting on Gaudí’s mosaic bench in Park Güell in Barcelona. Mel, sandwiched between the boys, is looking directly at me as I take the photo with my phone.

It’s a terrible shot, blurred and overexposed, with Noah doing rabbit ears behind his mother’s head. But it’s the last picture I ever took of Mel. It was our last summer as a family.

Get a grip, Jon. Get to work!

When I type “Slade Bristol appeal” into the search engine and hit enter, I get several hits. The most recent articles online – from The Plymouth Herald, The Bristol Press and The Bristol Post – were posted yesterday. Words catch my attention as I scroll down. Will the Court of Appeal grant Melissa Slade leave to appeal? … Melissa Slade to appeal against her murder conviction.

Melissa Slade.

Seeing her full name brings it all flooding back. My hand starts to shake over the touchpad of my laptop. I’m reluctant to go any further. But then I spot a piece from The Redcliffe Gazette at the bottom of the results page. Recognising the headline, I click on it. I feel my brow furrow as I catch sight of the byline: J. Hunt. I start to read the article, but I can’t take any of it in. It’s as if I’m reading a foreign language.

I go back to the top and start again. The words themselves remain meaningless, even though I’m the one who wrote them. But I know the gist of what they say.

I glance at the date. December 2013. Just after Slade’s trial. Eight months before our holiday in Barcelona. That was another lifetime. A different life.

A few seconds ago, I’d been staring at the holiday photo I’d taken of Mel and our boys. Now I find myself looking into Melissa Slade’s mesmerising green-blue eyes as she smiles her wide white smile at me, her sheer beauty at odds with the headline below her picture.

MELISSA SLADE SENTENCED TO LIFE FOR MURDER

This woman killed her daughter.

I’m not doing this. I’ll tell Claire to find someone else.

I’m suddenly aware of Kelly next to me, her loud sniffing filtering through my earplugs. I didn’t notice her come back. I delve into the inside pocket of my jacket, hanging across the back of my chair, and take out a clean handkerchief, which I offer to Kelly. When she has blown her nose, she manages a watery smile.

She says something, so I take out my earplugs and get her to repeat it.

‘Why’s she so hard on me?’

Claire can be hard on everyone. Because of her own quick competence and keen intelligence, she has little patience with people when she thinks they’re not pulling their weight. ‘I’m not sure, Kelly,’ I say. ‘Claire’s a perfectionist and expects high standards from everyone.’

I intend that to end the conversation, but I notice Kelly’s lower lip wobbling.

‘What did she say exactly?’ I ask. I don’t want her to start sobbing again. I don’t know how to deal with that sort of thing.

‘She said my latest copy was “unreadable due to numerous grammatical errors and spelling mistakes”.’

‘Well, that doesn’t sound too big a problem to sort out. Do you type up your stuff with the spellcheck on?’

I end up proposing to have a look at one of Kelly’s feature articles, more as a welcome distraction than out of the kindness of my heart. It’s an interesting story, about Bristol’s homeless, but it’s not particularly in-depth. While I correct it, I give Kelly a few pointers and tell her to find and interview someone living on the streets to add human interest to her article.

‘And get some photos,’ I say.

Next I read through a draft of one of Kelly’s pieces for the arts and entertainment page of our monthly print magazine. It’s a follow-up on an on-going local celebrity scandal, the sort of gossipy article I wouldn’t even glance at normally, but Kelly has written it in an appropriately sensationalist tone, and it only contains one spelling slip-up.

‘This is good, Kelly,’ I comment, which elicits a small smile.

She takes this as invitation to talk to me about her idea of setting up a weekly entertainment vlog.

‘I’ll have a word with Claire,’ I promise. ‘She should probably consider a rejuvenating facelift.’

Kelly grins, then pinches her eyebrows into a quick frown.

‘For The Rag, I mean,’ I add hastily. ‘Keep it,’ I say, as Kelly tries to hand the cotton hanky back to me. She scrunches it up in her hand.

She looks at me, a puzzled expression on her face, as if she’s trying to work me out. ‘I think my granddad is the only person I ever knew who carried cloth handkerchiefs on him.’

I’m not sure how to answer that, and I’m about to make a joke about her unflattering comparison, but I think the better of it. ‘I use them to clean my glasses,’ I say, shrugging.

It’s mid-afternoon before I can talk to Claire again. I’ve reread several articles on the Slade case, including my own. I’m still a bit hazy on some of the details, but I am clear about one thing. I’m not doing this.

It smells of cigarettes in Claire’s office. I suddenly feel like one – the itch has never completely disappeared, even after all these years as a non-smoker. I decide to scrounge a fag if she lights up, but she doesn’t appear to need one herself. She leans forward in her chair, resting her elbows on the desk and her chin on her hands.

I start by pitching Kelly’s vlog idea to Claire, aware that I’m putting off talking about Melissa Slade.

‘We’ll discuss it more fully at the next editorial meeting, but why not? She’ll be more presentable on screen than on paper,’ Claire comments dryly.

There’s a short silence, which Claire breaks. ‘Was there anything else?’

‘Er, yes. About Melissa Slade’s request for an appeal …’

‘Yes?’

‘Is there anyone else you could assign that to?’

‘Jonathan, it’s an interesting story and you’re the best I’ve got.’

‘Thank you, but can one of the others do it?’

Claire sighs. She takes a stick of chewing gum out of a packet on her desk, unwraps it and folds it into her mouth. ‘Is there some reason you can’t?’

Yes. There’s a very good reason I can’t. But there’s no way I’m going to tell Claire what it is. I don’t talk about it. Not to her. Not to anyone.

‘Well, it’s just that I’m really busy at the moment. You know?’ I can see from the expression on her face that I’m not convincing her. ‘Work-wise, I mean,’ I add. I don’t know if Claire has children, but I do know that she doesn’t tolerate anyone using their kids as an excuse for missing a deadline or as leverage for a lighter workload. ‘I’m going to the theatre tonight so I can write a review of The Cherry Orchard for The Mag, I’ve got a Sports Day to cover at the local comp tomorrow and—’

‘Jonathan, I’m giving you the opportunity to get in there ahead of the pack. This is investigative journalism.’

‘Claire. I can’t do it.’

‘Why the hell not?’

‘It’s personal.’ I have to make an effort not to raise my voice.

‘So is this.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean it has to be you. It can’t be anyone else. It wasn’t my idea. It came from … Your name …’ She breaks off, as if she realises she has said too much.

‘Who asked—?’

‘Anyway, you know as well as I do, there is no one else.’

I rack my brains, trying to think of another journo who could take the job. I have to get out of this.

‘You never know, Jonathan. Maybe they got it wrong and Melissa Slade was innocent all along.’

‘Yeah, right,’ I scoff.

‘That would be a great angle,’ Claire continues, as if I hadn’t spoken. ‘She did time when she didn’t do the crime.’

An image bursts into my mind. Melissa Slade, sitting in the dock at Bristol Crown Court. Impassive and cold. I was in that courtroom nearly every day. I didn’t see her shed a single tear. Not once during the whole three weeks of her trial.

‘She was found guilty,’ I argue. ‘She did it.’

I storm out of the Aquarium, only just refraining from slamming the door behind me.