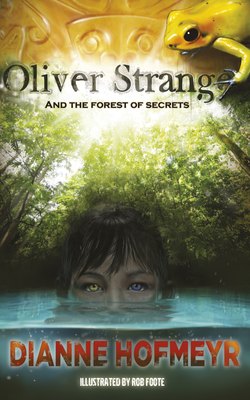

Читать книгу Oliver Strange and the Forest of Secrets - Dianne Hofmeyr - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5

ОглавлениеArrival

They looped along streams that joined up with other streams. Ollie was sure they were going around in circles, when a wooden pole jetty took him by surprise. Alongside it were two long wooden dugout canoes. Each canoe held a man leaning on a pole stuck into the water.

As the boat got closer, Ollie saw that the men were wearing only loincloths with plaited fibre ropes crossed over their chests. They had straight, shiny hair with pudding-bowl haircuts as if someone had put a basin over their heads to cut it. Patterns of red and black earth – or maybe they were tattoos – criss-crossed their cheeks and arms.

Ollie’s eyes flicked to the bottom of the boats. There were huge, curved machetes lying there but no AK-47s.

Rodrigo spoke to them in Spanish. Then his father and Rodrigo were speaking and his father was counting out money into his hand but Rodrigo seemed to be disagreeing.

His father shook his head. “You’ll get the rest when you come to fetch us in three weeks’ time. We’ll be at this landing on Monday in exactly two weeks. Make sure the boat is here and your truck has petrol.”

They transferred all the equipment into the dugout canoes, then Rodrigo backed the motorboat away in clouds of smoke. His mirror glasses flashed as he smiled and tipped his hand to his forehead. Ollie wasn’t sure it was a real smile.

The men untied the fibre ropes holding the canoes and pushed off from the jetty with their poles. In the deeper water they each picked up a long piece of wood shaped like an oar. They paddled standing up, thrusting from side to side with perfect balance as they negotiated the current.

The river was silky smooth and a deep emerald colour from the reflection of the trees. Foliage hung down in loops of thick green on either side. Around some bends, little pebbled banks appeared unexpectedly. There were bright flashes of birds, long tails streaming behind them, and strange monkey calls. In shafts of sunlight, butterflies wafted down like coloured flakes and flashes of sunlight sparked on the water and made it seem more jewel-like. He saw fish – too large to be piranhas but most of the time he spent ducking branches as the river narrowed.

The men stared straight ahead and answered briefly in Spanish when his father spoke to them. Ollie checked that the dictionary his grandma had given him was still in his pocket. He wished he’d spent more time learning Spanish.

“Let’s face it – we’re aliens here,” he whispered to Zinzi. It was odd how the silence was making him whisper.

She grinned back at him. “You look like an alien. You’re all green in this light and you’ve got reed stuff stuck in your hair.”

Ollie ruffled his hair. “At least it’s not a tarantula!” He studied the thick forest around them. “Looks impenetrable.”

His father nodded in the direction of the two men. “I bet they know every pathway. At the present rate of destruction, a third of this forest will be gone by the end of the century. Hundreds of acres of pristine forest are being lost in Colombia to coca cultivation and mining. Dozens of species which exist nowhere else in the world will vanish forever.”

His father was onto his pet subject and was peering around at the forest as if it had already disappeared. Ollie knew not to encourage him. “Do you think they know where they’re going?”

His father laughed. “As long as we’re going upstream, we’re heading in the right direction. Deeper into the forest. Further away from the coast.”

“But how much further?”

His father spoke to the man paddling.

“Nueve,” the man replied showing a curve with arm.

“I know!” Ollie interrupted. “Nine!”

Zinzi’s eyebrows shot up. “Nine kilometres? In this boat? It’ll take forever.”

His father laughed. “Nine curves or bends in the river.”

Ollie took his map from his backpack and a magnifying glass. It was like looking at the fine arteries of his hands. The Saija River was never-ending. It wound and wrinkled into lagoons and then narrowed again and turned corners until it finally flowed into the Pacific Ocean.

He tapped the map as he put it under Zinzi’s nose. “I don’t see any lost cities of gold marked on the map.”

Zinzi grinned. “That’s because they’re waiting for us to discover them!”

Without warning, there was a crack of thunder and rain started to pelt down. In seconds the river became pitted like hammered metal. Everyone scrambled about to make sure things were under cover and, at the same time, tried not to tip the canoes.

Around the next bend in the river, a flotilla of narrow reed rafts appeared as if by magic. Children were sitting astride them and pushing each other about and falling into the water in the rain. They swam like sleek otters.

No piranhas here then – nor alligators.

As the dugouts approached, the children scrambled back onto their rafts. Some of them kept circling in the water. As they got closer, Ollie saw pointy, whiskery faces. There were real otters swimming and diving between the children.

The children giggled and stared as the boats drew level with them. They were naked, except for some beads and strands of vines twisted with flowers like orchids that streamed down them, bedraggled in the rain and wet.

Zinzi nudged Ollie. “Makes sense to go naked.”

“What?”

“Just joking. But if it’s always raining and you’re wet and living next to a river with mud and leeches and other things attacking you, it seems an option.”

Around the next bend, groups of houses on stilts popped out from the green of the forest. As Ollie twisted around to look, more and more appeared – squarish with walls only halfway up and roofs made from woven palm leaves. They stood up on wooden posts about two metres off the ground. Water made crystal-drop fairylights along the edges of the palm-leaf roofs as the sun came out again.

One by one, people emerged into the clearing. The men had the same criss-crossings of woven palm strips on their chests and the women wore bright cloth wraps with strings of turquoise or green plastic beads. A few had silver-coin necklaces. They had straight, dark hair hanging down to their shoulders. Some had toddlers on their hips. All of them were tattooed with red and black patterns on their faces and across their chests and arms – even the toddlers. Between them, chickens and pigs and a few dogs scrabbled around in the mud and undergrowth.

Zinzi gave him a nudge. “It’s not exactly a city of gold.”

The man jumped from the canoe as it slid alongside a wooden jetty and tied it with a rope. “My name is Wau. Come.” He pointed to a platform that was larger than all the others and beckoned for Oliver’s father and the professor to follow. They climbed in single file up a log with notches cut into it that leant like a ladder against it.

His father called back over his shoulder. “Help unload while we get permission to stay in the village,” and then followed Wau.

Ollie hid a smile. Even though his father was fit, he couldn’t climb up the log as easily as even the oldest of the village men.

The boys and girls were out of the river now and came forward shyly at first and then started laughing and joking and teasing each other and running about – except one boy, who stood apart from the others, just staring hard at them.

He looked a bit older. He was wearing a wrap with leather bands around his wrists and across his shoulder. He stood with his hands on his hips, watching with his eyes screwed up against the bright light. It was hard to make out his exact expression but he wasn’t smiling.

Ollie jerked his head in the boy’s direction. “He doesn’t look too friendly. What do you think he wants?”

Zinzi shrugged. “Probably just curious to see all the stuff we’ve brought.”

Ollie looked at their heap of equipment and then at the students’ pile as well. It seemed a lot for collecting orchid and fungi data. He pointed at a huge mound of thick, rubbery plastic tied with a rope and nodded at Felix. “Qué?” It was at least one of the Spanish words he knew. “What?” he repeated, just in case.

Felix smiled. “Un bote.”

“A boat?”

“Sí.” He made as if he was pumping up a tyre and then made a whooshing sound and showed with his hands that it would get big.

“A blow-up boat? Big?”

“Sí. Grande.”

‘What’s he say, Ollie?”

“It’s a boat. I suppose one of those rubber ones that inflate.”

“A boat? To go further up the river?”

Felix had obviously understood and shook his head. “No es un bote para el río. Es un bote para los árboles.”

“What’s he say, Ollie?”

“Wait! Slow down. My Spanish is not that good. Árboles? Something to do with trees … I think.”

“He says it’s not for the river. It’s a boat for the trees.”

“A boat for the trees? What?” Ollie spun around to see who’d spoken English.

But there was no one there … just the kids jabbering in their own language. The silent boy had pushed off from the bank and was heading his dugout canoe upstream, paddling swiftly on either side. He didn’t look back.

“Did you hear that?”

“What?”

“That boy. He spoke English.”

“He couldn’t have. He’s Embera, Ollie.”