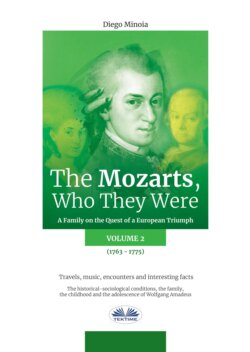

Читать книгу The Mozarts, Who They Were Volume 2 - Diego Minoia - Страница 7

Part 7

ОглавлениеThe Mozarts and the Grand European Tour / 2

22nd stop: Paris

Paris (from Friday 18 November 1763 to Tuesday 10 April 1764)

Some information about Paris...

Origins: already a Celtic settlement for centuries, when the Romans arrived in 53 B.C., it was a village occupied by the Parisi. Besieged and conquered, it was renamed Lutetia parisiorum (Lutetia of the Parisii). It then became a Roman city with thermal baths and an amphitheater, and in the 4th century it appeared for the first time with the name of Parisius (the city of Paris) in a text of the historian, Ammiano Marcellino.

During the Mozart's time: after relocating to the French Court of Versailles by will of Louis XIV in 1682, Paris held its place as the capital of France and the cultural and primary economic center. The presence of the residences of all of the principle aristocratic families of the kingdom and of a financial and entrepreneurial class on the rise made it a city rich in theaters and the fashion center that would disseminate throughout the rest of Europe.

Having reached Paris, the Mozarts then stayed at the Hôtel Beauvais, the residence of the Count Eyck, Ambassador of Bavaria. Describing his arrival at the French capital, Leopold Mozart writes that the outskirts of the city looked like a village, but as they travelled toward the center, the landscape changed with well-built and comfortable buildings where, he mentions the palace that hosted them, the planning was so functional, that “even the smallest corners were useful for something”. Obviously, his first complaint was the high cost of everything: nothing is at a good price except the wine. The list of expenses including the board (ten days, excluding bread and wine, cost 2 louis d'or, which corresponded to 22 Salzburg florins) of which there was the daily added cost of two bottles of wine (20 soldis) and bread (4 soldis) to a grand total in 48 Salzburg kreuzers for lunch and 48 soldis for dinner, evidently more frugal.

A complete list of the common coins in use in France and their value of conversion with the Salzburg coin (that Leopold, as tourist still do today, tried to simplify by rounding up the amounts) allowed Haganauer to better understand the extent of the expenses that the Mozart family had to sustain.

This objective of this information, as we have already said, served to deny the fact that the people in Salzburg should not believe that the Mozart family was becoming too wealthy, which would have created envy in the small Princely Court which, from faraway, would not have been possible to defuse.

A lot of the news he reserved to be communicated in person after his return, but some he thought important to write in his letters, for example, the water of Paris: “The worst thing here is the drinking water that is brought from the Seine River, which is revolting”. Actually, the Mozarts were in an enviable situation seeing as they lived in a noble palace and enjoyed the privileges that the rich procured by the master of the house, such as having water in the household while it was a daily and tiring undertaking for the commoners.

Leopold talks about the water-carriers of Paris, having received the “privilege” of the King, were made to pay a State tax to carry out their work which consisted of gathering the water from the river or the fountains and while carrying it in buckets, had to yell “water!” while walking the streets, selling it to who was in need and could pay. In any case, even while fortunate, the Mozarts, like the the aristocrats, had to undergo the daily routine to treat the water, which had to first be boiled and left to sit so the residuals settled to the bottom of the pail.

If this procedure was not scrupulously followed, the consequences were unpleasant; the best case scenario, diarrhea, if not worse. Leopold said that almost all of the tourists who stayed in Paris in the beginning, suffered from this ailment, and that the entire family had to endure it, even if in a more tolerable form.

Water in the 18th century in Europe

To better understand how things have changed in terms of use and abuse over the centuries, the example of water is a perfect representation. In our modern cities today, we take for granted this precious resource. All we have to do is turn a handle and it appears, hot or cold as needed.

It has been calculated that the consumption of water per capita (for domestic, industrial, public and agricultural use) has increased from 200 liters a day during the mid 1900s to 2,000 liters a day in modern times (and beyond that in the more wasteful areas). To have an immediate perception of the difference, just imagine that in the 1700s the average Parisian had 5 liters of water a day available, and 10 liters available at the turn of the century.

It is obvious, with the quantity of water available, that personal hygiene was not among the first and foremost of priorities. Baths were taken in the river in the summer (even though there was a preconceived notion that this practice was harmful to the male gender's body, fearing a loss of physical strength) and in the few public baths.

Approximately 300 bathtubs were available in Paris in 1789 in the public baths and about an additional thousand private bathtubs in the homes of the nobility (but only a tenth of the aristocratic palaces in 1750 had an actual bathroom, although in Versailles, Louis XVI installed six).

So during Mozart's epoch in the European cities, water was not a resource conveniently available to all as it is today.

The scarcity of water was remedied by the amount of underclothes one possessed, moving toward the importance of “good manners”. An unclean body was “covered” by clean clothing (and that is how white clothing became associated with personal virtue).

It was believed that fresh underclothing absorbed the uncleanliness and sweat from the body, leaving it clean. It was, therefore, considered appropriate, as was also ordered by the doctor, to change one's shirt every 2/3 days, more often in the summer or if one was wealthy.

Only the more visible parts of the body were given more attention and care and washed with water: face, hands, neck.

Only a fortunate few (nobility, high-level functionaries, religious institutions and hospitals) received particular “privileges” that allowed them direct access to the public aqueducts, which in any case, were needed by only some neighborhoods.

For the rest, they obtained their provision of water from the common well, at the neighborhood fountain or from traveling salesmen who supplied vessels of water from rivers or canals and went from house to house selling water by the bucket.

However, water from rivers and canals, especially those within the cities, were becoming ever more polluted due to the continual outpouring of waste directly into the watercourses: tanneries, butchers, laundrywomen, etc.

We know that from the 17th century, the main European rivers like the Thames and the Seine, were defined as latrines (the writer Beaumarchais “sarcastically” said that “in the evening the Parisians drink what they had dumped into the river that morning”), but this is still where the Londoners and Parisians obtained the essential quantity of water to quench the thirst of the population.

From the canal system that brought the city's river water to the neighboring areas, the zones located farther away were excluded, and had to meet their need for water by digging common wells (in the courtyards of the residences or in the squares of the neighborhood) or for the wealthy, privately.

But not even wells offered clear water, polluted like the phreatic stratum from infiltrations of every kind, from wells black with cemeterial waste of which epidemics such as cholera and typhus fever originated. When water was not used for external purposes, it had to be boiled.

White gold rapidly became a “necessary luxury”, so much so as to drive the States to massive investments in aqueducts which, as was the case in Paris (nearly by contrast) were financed with a tax on wine consumed in the city.

For a long time running water would be a luxury for only a few and, for those who were lucky enough to live near a fountain (others had to walk long distances with the weight of the supply on their shoulders), the long lines meant a long wait.

It was the women who were prevalently responsible to fetch the water and could carry an average of 15 liters at a time, and then after the tiring journey, had to carry the water four, five or even six flights of stairs to the apartment.

In 1782, hydraulic pumps were introduced by the Perrier brothers that drew water from the Siene and distributed it in the available canalizations, allowing at least a partial operation of cleansing of the main streets, creating a consequential improvement of the salubrity of the air.

Even so, most of the citizens were obliged to continue getting their water from the well and the public fountains, unless they were able to afford to purchase from one of the 20,000 carriers/sellers that were in constant circulation on the streets with their buckets of water.

Another bit of interesting information that Leopold gives us regards the postal service in Paris. On one hand, he complained about the cost of sending/receiving the mail for/from out of town; the letters were weighed and exorbitantly taxed, so he asked Hagenauer to use thin and lightweight paper and for Hagenauer's son, Johann (whose job it was to write any news or facts from Salzburg or anything that might be of interest) to use the smallest calligraphy possible. On the other hand, he commended the so-called “local postal service” that allowed rapid communication in and around Paris (the city was divided into districts and the postage went out four times a day in order to be distributed in the various neighborhoods).

The dimensions of the city, in fact, made moving around the city a long and expensive venture at times, having to pay for public transport (Leopold felt it was of the utmost importance to present himself respectably and avoided traveling on foot to the aristocrat's homes soiled and sweaty from the dirty streets).

One confirmation of his reluctance to walk we find in a letter dated 9 January 1764 when he had just arrived in Paris from Versailles, where he wrote to the notary Le Noir, that he had come to his house only to find that he was out, and highlights the fact that “I even walked to your house; a noteworthy effort!”. To evaluate how noteworthy the distance was, we know that van Eyck's residence, where the Mozarts were staying, was at the Place de Vosges, while the notary Le Noir's house was in rue d'Echelle, behind the Louvre and the Tuileries Gardens, approximately 2.5 kilometers of flatland which was the equivalent of a 30 minute walk.

This letter to the notary illustrates another interesting fact: whoever did not have a butler to greet and invite the guests in while the master of the house was out, left a marker board at the entrance where the visitors could write their names in order to know who had paid a visit...and this is what Leopold did. Whenever possible, Leopold used the “fiacre”, an enumerated public carriage (something like today's taxi) that he defined as miserable, while on the more important occasions he was obliged to hire a “depot carriage” which was very expensive since it was rented for the entire day, but allowed the carriage to enter directly into the courtyards of the noble palaces (while the fiacre would make its stop on the street and the guests had to walk to the entrance, lowering the perception of their social and economical status).

As we have already said, the Mozarts reached Paris on 18 November 1763 and it was Leopold's desire to get busy with organizing the exhibitions, obtaining glory and money. But as luck would have it, a mournful event had taken place that involved the French Court (the death from smallpox of Infanta of Spain Princess Isabella of Parma, niece of Louis XV), imposing a period of mourning during which fun and entertainment were suspended. The Mozarts had to wait well into December before they were able to present themselves to the principle people of the city, but thanks to the Baron Friedrich Melchior von Grimm, writer and person in charge of the affairs in Paris of the Princedom of Frankfurt, put in a good word for them and they were invited to Versailles, seat of the Court of Louis XV, where they were guests for sixteen days at the Au Comier Inn.

Friedrich Melchior von Grimm (1723-1807) writer and diplomat

Appointed Secretary to the Count von Friesen in Paris in 1749, he became responsible for the affairs for the Princedom of Frankfurt.

He was a person of vast culture, and friend of the encyclopedia writers Rousseau, Diderot and Voltaire, not to mention editor of the two-year newsletter “Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique” whose purpose was to inform the European Courts (from the German to the Czar of Russia) of the new Parisian cultural fashions and trends, intended in that period to be imitated throughout Europe.

In the dispute between those who supported Italian opera and those who admired the style of Gluck, he took sides, openly and with all the weight of his Parisian aristocratic relations in favor of the Italian style.

The optimal habitual association with, and lover to Louise d'Epinay, writer and entertainer of one of the most famous Parisian “parlors” allowed his social ascension that led him to receive diplomatic posts until he was nominated Baron in 1774 by the Empress of Austria Maria Theresa. As a literary and musical critic, he wrote for the famous magazine Mercure de France.

In the Mozart's first journey to Paris, he played an essential role in their success. Though later, when Wolfgang went to Paris alone with his mother, Grimm was cold and could not stand him as in the past. In his final letter from Paris to his friend Hagenauer, Leopold Mozart spoke of Grimm in the following: “...this man, my good friend, Mr. Grimm, it is thanks to him that here I have been able to obtain everything”.

Even while provided with many letters of recommendation (among which that of the Count de Chatelet French Ambassador in Vienna, the Count Starhemberg Imperial Austrian Emissary in Paris, the Count von Cobenzl Minister of Brussels, the Prince of Conti, etc.), according to Leopold, none of them were good for anything.

Only Count Grimm “did everything”...and imagine, this aid all came from a letter written by the wife of a merchant from Frankfurt who he had met by pure chance in that city where they had stopped over on their way to Paris!

So, he gave Leopold Mozart 80 gold florins for the performance of the children at his home, then he set about distributing 320 tickets for the first concert at the theater of Mr. Felix, paying for the wax needed for the 60 candles per table to illuminate the room.

The early information on Versailles sent to Salzburg by Leopold Mozart are a bit amusing as, while speaking about the Marquise of Pompadour (former mistress of King Louis XV), he compares her to the defunct Mrs. Stainer, a Salzburg friend. Regarding her personality though, he says that she is extremely conceited and still continues to orchestrate everything (even though she had not officially been the King's mistress for at least a dozen years – A/N). He describes her as a woman with an uncommon spirit, large and corpulent, but well-proportioned, blonde, still attractive and was surely very beautiful in her youth, seeing as she had enraptured the King. The Pompadour apartments at Versailles, which faced the gardens, were described by Leopold Mozart as “a paradise”, while the palace in the Faubourg St. Honoré, used as the Parisian residence was described as magnificent. The palace (today it is the official residence of the French President of the Republic) had been built just a few decades previous for the Count d'Evreux; it was bought in 1753 by King Louis XV for 730,000 livres and donated to Madame de Pompadour, his favorite at that time. Evidently, the Mozarts had been admitted since Leopold describes the music room that housed a golden harpsichord painted “with great art” and on the walls hung two life size paintings of Madame de Pompadour and the King Louis XV. The cost of living was also very high at Versailles, and luckily in that period, it was very hot writes Leopold (in December?), otherwise there would have been the cost of wood for the price of 5 soldis per log to warm the lodging. The Mozarts lived in Versailles for two weeks on a road that, keeping in mind the two children of the family and their talents, was appropriately named: Rue des Bon Enfants (Road of the Good Children).

The comfort of a heating system

Relocating from one society that was used to the cold temperatures, or rather, protecting themselves with heavy clothing, allows us to look at the relatively rapid development of the comforts of heating: first in public places (hospitals, barracks, offices) and then private homes.

The wall fireplace appears to have been invented by the Italians (we first hear of it in Venice around the 13th century) and, compared to a central open fire, it allowed the rooms to be less invaded by smoke, but was not very efficient in dispersing the heat. Moreover, it “roasted” one's face and front of the body, leaving the backside freezing cold.

The newest invention was the stove (in iron, cast iron or ceramic) that saved fuel and offered a more homogeneous and pleasant heat. The fireplace required repeated operations and maintenance to keep it functioning: supplies of wood (to purchase, stack, carry into the house, disposing the ashes or using them for the monthly laundry).

We find a reference to the weight of the chore related to wood in a letter from Leopold Mozart to Hagenauer from Munich, dated 10 November 1766: “I ask you, or rather your wife, to find us a good housekeeper, above all in this period in which we need to continually fill the stoves with wood. These things are essential, or rather a malum necessarium (a necessary evil – A/N)”.

The embers were covered in the evening to prevent frequent household fires and to facilitate starting the fire back up in the morning. Smoke was the unavoidable companion in most homes, where the stove was central to the domestic activities in the kitchen.

The rooms, if there were any, were outdoors, so to stay warm during the cold, it was necessary to sleep with heavy clothing, possibly heating the bedding with bed warmers and braziers.

Stoves were certainly the most convenient and the wealthy, naturally, were the first to have access, even in more than one room of their apartments while keeping the antique and imposing fireplaces in the entertainment salons which was becoming a fading symbol of power.

Satisfying the new massive need for heat in the household provoked an increase in the demand for wood (this was before other forms of combustion, such as coal, were available at the turn of the century) which caused an increase in the price of up to 60/70%.

During the coldest winters, the poor ransacked the woods and forests, risking getting caught by the King's Guards or by the nobility's property foresters..

But wood, peat and coal were not the only forms of combustion used: the poor had less and could not afford to be queasy when it came to foul odor, so they used manure that, duly dried out had the caloric power equal to peat and even superior to wood (4.0 compared to an average measure of 3.5 of wood).

If finding manure was easy enough in the country, the poor in the city had to gather the horses' “leftovers”.

Even the windows (a certified innovation in Italian cities such as Genoa and Florence at the turn of the 14th century) gradually substituted wooden shutters with canvases soaked in turpentine (serving to make the fabric semi-transparent) which contributed to the struggle against the cold.

With glass windows, the necessity for light and heat merged: glass became lighter and clearer, illuminating indoor establishments which had for centuries had been dark and damp. Initially, small and round glass windows joined by lead (as can be seen in cathedrals) were invented, progressing with construction techniques to larger and clearer window panes.

Fortunately, the exhibitions of the two prodigious children at the Court began to show some profit. A gold tobacco tin and a small, but very valuable watch was given to Wolfgang by the Countess Adrienne-Catherine de Noailles de Tessé (the Dame of Honor of the Dauphin and mistress of the powerful Prince of Conti to which Wolfgang had dedicated two sonatas on the harpsichord which was composed and published in the following weeks), a small transparent and engraved gold tobacco tin for Nannerl and a silver pocket-sized escritoire with a matching silver pen for Wolfgang from the Princess of Carignano. Other gifts arrived in the following days: a red tobacco tin with gold rings, a tobacco tin in glass material ingrained in gold, a tobacco tin in “laque Martin” (also known as “vernis Martin”, invented in 1728 by the Martin brothers, an imitation of Chinese and Japanese lacquer, it was much more economical as it was initially produced with copal, a resinous substance similar to amber) with flowers and pastoral instruments in enamaled gold, a tiny ring mounted in gold with an antique setting, as well as a quantity of gifts whose value Leopold did not underestimate (ribbons for daggers, arm ribbons and tassels, tiny flowers for Nannerl's bonnets, small kerchieves and other necessary accessories to be fashionable in Paris). One last curious gift was a solid gold toothpick holder given to Nannerl.

Table settings

In reference to the gift of the toothpick holder, this allows us to speak briefly about some innovations that were forthcoming and were to become part of future etiquette: table settings. Related to food at the beginning of the 1700s, the objects that constituted the instruments at the table were the spoon, the fork and the knife.

The name “spoon”, already known from Ancient Egypt and by the Romans, is derived from cochlea (seashell) and during the Middle Ages it was made of wood or for the wealthy, gold or silver, ivory or crystal.

The knife originated even farther back with a much more aggressive history. This is possibly why its use was limited, for fear of wounding a dining companion or using it as a weapon in the case of a dispute (in China, it was against the law) up till the Renaissance Period when a rounded tip was invented, surely much safer.

The fork appeared in the modern use of bringing one's food to their mouth in Venice in 955 when the Greek Princess Argilio (who probably learned to use it in Byzantium) flaunted hers on the occasion of her wedding with her son to the Doge Pietro III Candiano.

The diffusion of this useful instrument, however, had to come to terms with the Roman Catholic Church which, due to the orthodox schism, identified the use of the fork with the Byzantium use and banded its use as demonic.

To better understand the deeply anchored curse of the mentality of people, we know of one cultured person from the 17th century, Claudio Monteverdi, who when obliged to use a fork for good manners for his hosts, later requested three masses to pardon his sin. The fork was introduced at the French Court, needless to say, by Catherine de' Medici, whose son Henry III, went as far as legislating (without much success) its common use.

During those days of mourning, the Mozarts dressed, at least in part, according to Parisian fashion; Leopold cites Wolfgang's black outfit complete with a French hat. Actually, the Mozart family had four black outfits tailored for the death of the Prince-Elector of Saxony Frederick Christian, brother of the Dauphine of France.

The rules of mourning

Death in the 18th century was frequent, whether due to disease, war or an epidemic.

Often times, as we learn in the Mozartian epistolary, an event of mourning jeopardized Leopold Mozart's plans, ruining potential earnings and weeks of contacts and maneuvers in order to obtain an invitation to a certain court or palace for the exhibitions of his children.

The aesthetics of mourning were well-defined; the dress code of the family members of the defunct, as well as the length of time the clothing should be worn..

In the case of the death of a monarch, the mourning process involved all of the subjects with evident exterior displays that included mourning wear of the nobility to the black band worn on the upper arm of the citizens.

On the occasion of the death of a regal mourning, all events and shows were postponed for weeks or even months, as was the case that involved the Mozarts and their projects in Vienna: the death of the Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria, betrothed to the King of Naples Ferdinand IV of the House of Bourbon that provoked the suspension of every event for six weeks.

In Versailles, the rigorous protocol required that the mourning dress of the King was to be purple while that of the Queen was to be white. This was declared for the death of any member belonging to the royal family or of any foreign monarch.

There was no mourning for a child under the age of seven years old, as it was considered below the age of descretion. In any case, infancy death was common and accepted with resignation.

For widows, the rules were equally as rigid. The entire household was covered in black, including paintings and mirrors and the bedroom of the widow was painted over in black. The widow had to wear a black veil and dress in the same color.

The regulations for mourning in France, as well as other European countries, were even imposed by law. In France in 1716 the duration of mourning was shortened to half by law establishing the widow a duration of one year and six weeks.

During the first four and a half months, the widowed dame had to wear a cape, surcoat and a cheesecloth skirt, then for the next three months she had to wear a dress of crêpe and wool, and for the following three months she wore clothes in silk and chiffon, and finally for the remaining six weeks she began the “half mourning” where the dress code was less severe and the use of jewelry was allowed.

Leopold calculated that the purchase of clothing and the expenses to reach the location at the Royal Palace of Versailles amounted to 26/27 Louis d'or in sixteen days, since in Versailles “horse cabs” and “rental carriages” were not available, only wagons. Due to the rainy days, in order to avoid getting their clothes muddy before approaching the Court, the four Mozarts had to take round trips with two wagons for a cost of 12 soldi each. The mother and Nannerl traveled together on one and Leopold and Wolfgang on the other. Up until that time, the Mozarts had received in cash, while waiting for the King's donations, the amount of 12 Louis d'or which only covered half of the sustained expenses. The 50 Louis d'or that were donated by the King through the Office of the Menus plaisir du Roy (responsible for the lesser royal pleasures) were held in a tabacco shop and allowed them to make ends meet for the relocation to Versailles (without including the value of the abovementioned gifts).

While in Paris, the Mozarts attempted to speak French, at least the basics that would allow them as foreigners to communicate with the locals, but judging from the errors found in the epistolary, their fluency of the language left much to be desired. Even in Wolfgang's letters in the following years, we note many spelling and grammatical errors in his use of the French and Italian languages, having learned by the seat of his pants through opera libretti and during the course of his three journeys to Italy. In a letter from Paris, peculiarly addressed to Hagenauer's wife, Leopold expresses his opinion on the beauty of French women. His impression was that they were so excessively made-up, “unnatural”, he says, “like the dolls that are made in Berchtesgaden” (a place in the Bavarian Alps 25 kilometers from Salzburg) “that even if they are pretty, they are repelling in the eyes of an honest German.”.

Beauty products

On the vanity table of an elegant dame (without excluding husbands, who also used various creams and makeup) there were many products aimed at creating fashionable pale and fresh skin, as well as substances to alter the tone, false beauty marks, etc.

Since the 16th century, there had already been books printed with recipes of every type for curing diseases or for the preparation of beauty oils and creams, such as “I Secreti Universali in Ogni Materia” by Thimoteo Rossello, published in Venice in 1575 whose second volume contained a list of a dozen recipes for making hair blond and beautiful and how to have splendid white skin.

Several similar publications were also widespread in the 18th century, for example “La Toilette de Venus” published in 1771, or “La Toilette de Flore” from the doctor Pierre-Joseph Buc'hoz who offered recipes for oils and beauty creams derived from flowers and plants.

Transparent and brilliant skin (the fashion to follow was the “convent complexion”) in the 1700s was praised enough to forgive a woman who displayed even stupidity or unrefined behavior.

Men and women who applied make-up used ceruse to whiten their complexion (originally derived from egg whites and later a white pigment made with toxic lead) and rouge for lips and cheeks (originally derived from animal substances such as scarlet-colored insects or plant-based red sandalwood, later derived from minerals such as lead, minium and sulfur baked in ovens at high temperature), not to mention the dozens of essences, creams, pastes and eau de cologne.

In one of his writings, the Knight d'Elbée calculates the sales of 2,000,000 jars of rouge and reports the words of Montclar (among the most famous vendors of rouge in Paris), who confirms having sold three dozen jars of rouge a year to Signor Dugazon (the actor, Jean-Baptiste-Henry Gourgaud), while his wife, the actress Rose Lefèvre purchased six dozen jars from Bellioni and Trial each for six francs a jar.

The make-up or rouge was not, however, chosen by its tone or color. It needed to make a statement about the person wearing it, so much so, that a certain type was reserved for the dames of social class as opposed to the dames of the Court (the princesses wore a very intense color), while another color was appropriate for the middle class, and obviously another for the courtesans.

There were also lotions: to lighten the color of the skin or to give it a blush tone, to enhance and to wash it, to eliminate freckles and blackheads, to rejuvinate skin yellowed by age, etc.

Entire fortunes were squandered on beauty products, to the point of boiling gold foil in lemon juice in order to obtain an otherworldly complexion in the light of day.

Then there were the ointments to repair the scars on the skin from disease, smallpox in particular which was widespread in that era, products for hair, nails and for teeth.

And what about false moles, also known as beauty marks? They were tiny pieces of sticky cloth in various shapes (hearts, moons, stars, etc.), purchased from the famous manufacturer Madame Dulac, meant to complete the make-up with personality and spirit.

The position of these false beauty marks (each with an assigned name) were rigorously imposed by well known rules: the assassin (at the corner of the eye), the romantic (in the middle of the cheek), the cherished (near the mouth), the regal (on the forehead), etc.

To complete the preparation of the head of the noblewoman before leaving the house neccessitated the setting and styling of her hair which, for the great noblewomen on important occasions usually involved true architectural creations by the greatest hairdressers in Paris.

The height of the hairstyles reached towering limits, so much so that caricaturists represented the hairdressers standing on stools, if not ladders to reach the peaks while they worked on their creations.

If during the early part of the 18th century, brown was the favored standard for beauty of hair color, at the turn of the century, fashion abruptly changed: dark hair fell out of favor to blue eyes and blond hair.

A pale complexion, though, remained an essential element. To reach this objective, many underwent a bloodletting procedure often many times a day through the application of bloodsuckers or being stuck with a pin in an exterior vein.

Even religious devotion and the morality of the Parisians gave Leopold reason to express many of his sarcastic doubts. Regarding the business that the Mozarts expected from the exhibitions in Versailles, all moved so slowly that Leopold complained that at the Court “things go at a snail's pace, even more than at other Courts” mostly because every entertainment activity (festivities, concerts, theatrical performances, etc.) had to pass through the evaluation and the organization of a special commission of the Court, the Menus-plaisirs du Roi (the lesser royal pleasures of the King). Leopold Mozart writes to Hagenauer's wife, illustrating some of the Parisian Court's different practices compared to what was done in Vienna: in Versailles you do not kiss the hand of royalty or bother them with requests and pleas, least of all during the ceremony of the “passage” (the procession between the two wings of courtiers that the royal family practiced while going to mass at the chapel inside the palace). It was not customary to display honor to royalty by bowing the head over a bended knee as was done in other European Courts. Instead, one was to stand up straight and comfortably and watch the members of the royal family walk by.

In reference to these customs, Leopold does not miss the chance to remark with great surprise that among the guests present, the daughters of the King stopped to speak with Wolfgang and Nannerl, letting them kiss their hands and doing likewise. Even on the evening of the New Year during the “grand couvert” (royal dinner where numerous courtiers and guests stood by watching the high ranking social class) held in the Hearth Hall that also served as the antechamber to the Queen's apartments, “My Mr. Wolfgangus had the honor to pass the entire evening near the Queen”. He conversed with her (she spoke German very well as she was of Polish origin and spent some years of her youth in Germany) and even ate the food offered by her. Leopold also draws attention to the fact that they were all accompanied to the “grand couvert” hall (given the large crowd that flocked in order to watch the dinner) by the Swiss Guards and that he, too, was near Wolfgang while his wife and Nannerl were placed near Louis, Dauphin of France (heir to the throne) and one of the daughters of the King.

The Swiss Guards

Today when we talk about the Swiss Guards, the first thing that comes to mind are the pictoresque soldiers at the State of the Vatican, with their colorful Renaissance uniforms that guard of honor of the Pope.

In truth, dating back to the 14th century during the epoch of the Hundred Years' War, many European kings used Swiss mercenaries to form military corps for their protection.

The first monarch to create a Swiss Guard corp was Louis XI and his successor Charles VIII progressively increased the number to 100, hence the name Cent suisses (the Hundred Swiss).

Between the end of the 1400s and the beginning of the 1500s, the Papal State followed the example of the King of France to the point that Julius II had at his service 150 Swiss Guards that demonstrated their faith during the course of the Sack of Rome which was carried out by the German mercenary Landsknecht soldiers enrolled in Emporer Charles V's army.

Even the Savoys had their Swiss Guards in the 16th century, and during the 18th century the Swiss were personal guards to Frederick I of Prussia, the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, Joseph I of Portugal and even utilized by Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Mozarts arrived in Versailles on the evening of Christmas Eve in 1763 and were able to watch the traditional mass in the Royal Chapel: the first at midnight, a second later during the night, a third at sunrise, the last at the early morning hours of Christmas Day. As a musician, Leopold voices his opinions of the music: good and bad, he says, specifying that the pieces for only voices and the arias were cold and lacked quality, meaning the French (evidently Leopold did not enjoy French vocal style, preferring Italian and German). However, he found the choral pieces excellent, so much so, that he took advantage of the opportunity to continue Wolfgang's musical and stylistic training, accompanying him everyday to the King's mass held at 1 pm in the Royal Chapel (unless the King decided to go hunting, in which case the mass was anticipated to 10 am).

The blatent visibility of the wealth accumulated by the richest Parisian aristocrats, from the fermiers généraux (private parties who received the privilege of collecting taxes in certain areas, becoming excessively wealthy) and the important upper class bankers (about a hundred people altogether according to Leopold) struck the moderate Salzburg enough to consider them “astonishingly mad”. The display even led women to wear fur coats in warm weather: fur collars, fur bands in their hair in place of flowers, ribbons of fur around their arms. At the opera and receptions, the great dames who could afford it flaunted the most luxurious furs (ermine, wolf pelts, otter, sable). Particularly favored were “hand muffs”, in fur or angora in cilinder shape (so-called barrel) or draping majestically to the ground. However, the use and abuse of fur was not only limited to women.

Men wore daggers adorned with ribbons which were highly fashionable in Paris, made of very thin fur, causing Leopold to mockingly comment that something so ridiculous would surely impede the dagger from freezing.

Even excessive love for luxury by the French was reproached by Leopold, in particular the habit of sending newborns to caretakers in the countryside, entrusting them to a “tenant” who would distribute the children to the wives of farmers, where they wrote the names of the parents and guardians in a ledger in collaboration with the local parish in exchange of an offering for their “certification”.

The “care” of children in the 18th century in Paris – To be born female was a difficult fate

In general, when a female child was born, it was a disappointment for the parents. Wealthy or poor, the reaction was the same.

No celebrations and above all, a fate marked by a “lesser” future in comparison to male children. It would not be her who carried the family lineage, or to inherit property and public positions (in the case of noble families) and it would not be her to contribute to the sustainance of the family with physical strength, unless helping in the household or working as a housekeeper (in the case of poor families).

In the aristocratic homes, newborns were immediately entrusted to the tenants and taken away from their homes and mothers until they were weaned.

The tenants were often ignorant farmers that neglected the children often to the point of death or, as happened to Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (Prince and later an astute politician for all seasons), was rendered an invalid.

It appears, in fact, that Talleyrand had a permanent limp due to a fall from a chair that was too high of which the absent-minded tenant had left him unattended.

After the children were weaned, they were returned to their families and were entrusted to a nanny who looked after their every need, from basic education (reading and writing, catechism, some bible study) to attending to their personal habits, often with the aid of the many publications dedicated to educating children.

There was no familiarity with the mother, let alone with the father, if not on the occasion of the morning visit to the mother's room where she received him or her with indifference, paying more attention to her dogs.

From a very young age, the wealthy daughters were dressed like the adult women (corset, farthingdale, noteworthy hairstyles complete with a hat, etc.) and were given dolls with complete wardrobes.

The weekly magazine of information Le Mercure de France announced to its readers in 1722 that the Duchess d'Orleans had given the Dauphine of France (wife of the Dauphin who was first born son and heir to the King of France) a doll with a complete wardrobe and jewels of astronomical value for those times: £22,000.

When the wealthy girl reached the age of six or seven years old, she began to receive dance, singing and music (harpsichord) lessons in order to prepare her for her role in society...and in the end would be sent to a convent, based on the prestige of the other girls she consorted with.

It was obviously not a monastic life as we are accustomed to imagine it today but a kind of boarding school where the girls lived a relatively secluded and morally "guaranteed" life: there were well-furnished apartments for girls of noble lineage and in the most prestigious convents, contacts and friendships were intertwined between the girls who, once they were released and returned to the world through marriage, would be able to obtain social and economic advantages for the family of origin and that of the husband.

It often happened that the young women were married by exclusive decision of the family without consulting the daughter from the age of twelve or thirteen and then sent back to the convent until they reached the appropriate age to consummate the marriage.

Thus it was for a daughter of Madame de Genlis, married at the age of twelve, and for the Marquise de Mirabeau of which she became the widow of the Marquis de Sauveboeuf at thirteen.

In particular convents there was also a curious typology of girls who, even without pronouncing binding religious vows, received a habit and the honorary title of Canoness, which gave prestige to them and to the families to which they belong: however they had the obligation to reside in the convent two out of three years.

The Canonesses were divided, according to age, into Dame aunts, each of whom was entrusted with a Lady niece, who would receive her support to build relationships with the other Ladies and, on the death of her aunt, would inherit her furniture, the jewels and any income and benefits related to her office in the convent.

The main convents and most coveted by the noble families were that of Fontevrault, in the Loire Region (where the Daughters of France, the daughters of the Kings and Dauphins of France were educated), that of Penthémont (where the Princesses were educated and "they withdrew" the Dame of quality once they became elderly or widows).

Hospitality in these convents was not free, on the contrary. In 1757 the cost could range, in Paris, from 400 to 600 livres to which other expenses were added: 300 livre for the maid plus more money for the trunk, bed and furniture, for heating wood and for candles or oil for lighting, for washing linen, etc.

At the convent of Penthémont, the most expensive, there was the distinction between ordinary pension (600 livre) and extraordinary (800 livre which became 1,000 if the boarders desired the honor of eating at the Mother Superior's table).

At the end of their preparation in the most prestigious convents the girls were ready for marriage and, if we give credit to what their contemporaries thought, "they knew everything without having learned anything".

Marriage, for most of these girls, simply represented the fulfillment of the family project and had value for the status she would give them, based on her husband's condition, and for the luxury and comfort she would allow.

As new brides, they would then begin the tour of visits to the aristocratic circle of friendly families of their family and their husband to affirm her new condition as married women ready for society life, with a side of fashionable clothes, jewelry, hairstyles. to show off at the Opera and on every occasion, especially if you belonged to the elite who had the opportunity to access the "presentation" at the Court.

At that point, to be capable, the girl had to learn the fashionable words and use them naturally: Amazing, Divine, Miraculous, are terms to be used to describe a musical performance at the Opera rather than a new hairstyle or a new dance step.

A lady's day did not begin until eleven o'clock, when she woke up, she called the maid who helped her wash and dress while the mistress stroked the inevitable pet dog that slept in her room.

The fact that the habit of nursing newborn children to ignorant peasants who often neglected them was widespread not only among the aristocrats but also in decidedly less wealthy sections of the population (the cost, in fact, was very low) which caused disabilities that, for the poor meant misery and marginalization for the rest of their lives. Leopold observes that in Paris one could not easily find a place that was not full of miserable and crippled people.

In and out of churches or walking in the streets one was continually subjected to requests for money from the blind, paralyzed, crippled, pustular beggars, people whose pigs had devoured a hand as children, or who had fallen into the fire and burned their arms while their keepers had left them alone to go to work in the fields. All this disgusted Leopold, who avoided looking at those poor people.

The poor

Social inequalities were extremely large in the 18th century.

In the face of an aristocratic class, which lived in luxury and which was "forbidden" to work (thus living off the remaining part of the population) and among the large and middle bourgeoisie (which got along quite well thanks to finance, trade and professions), there were crowds of poor people and going farther down the social ladder, of miserable people without a home, food or family.

Of Neapolitan beggars, Prince Strongoli says in 1783, that "they overflowed without a family" because misery often prevented the formation of family ties or even caused their disintegration, with husbands abandoning their families or children leaving to seek better fate elsewhere, usually in some city where they hoped for more opportunities.

The needy not only included slackers and wanderers by choice but also all those who were unable to earn their daily bread because they were too old or too young (although children started working at a very young age), disabled or sick.

During Prince Strongoli's time, it is estimated that in Naples a quarter of the population (100,000 out of 400,000 inhabitants) belonged to the poor or miserable class.

The number of the poor then increased or decreased also on the basis of contingencies: famines, wars, job losses, diseases, epidemics could increase the percentages even to 50% or more in moments of the worst crisis.

Without reaching the frightening numbers of Naples at the end of the 1700s, poverty was also great in other European cities: from south to north (Rome, Florence, Venice, Lyon, Toledo, Norwich, Salisbury) ranging between 4% and 8% of the population.

One can therefore easily imagine the enormous mass of miserable and poor people in Europe, considering that the continent's population amounted to about 140 million in the mid-1700s rising to 180 million on the threshold of the French Revolution.

A small part of the enormous mass of poor children, because they were orphans or belonging to families who were unable to feed and care for them, were "taken care of" by the Conservatories or Hospitals which, born in Naples, Venice and other Italian cities during the 16th century, also spread to other large European cities.

In his letters, Leopold also refers in passing to the remains of the famous "Querelle des bouffons", the dispute between the supporters of the Italian theatrical musical style (performance of the Serva padrona – “The Maid Turned Mistress”by Pergolesi) among which the encyclopedists with Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the front row, and the admirers of the French style à la Lully (who, incidentally, Giovan Battista Lulli, was also Italian, in spite of the French name). Although the discussion had been resolved a dozen years earlier, evidently the controversial aftermath had not completely subsided and Leopold does not hold back from giving his opinion on the matter: French music, all of it, is worth nothing while the German musicians present in Paris or whose printed compositions were widespread in the French capital (Schobert, Eckard, Honauer, etc.) were helping to change the musical taste of their French colleagues. Some of the main composers operating in Paris, Leopold writes, had brought their published compositions to Mozarts while Wolfgang himself had just delivered 4 Sonatas for harpsichord with violin accompaniment marked in the Mozart catalog as K6 and K7 (those dedicated to the Delfina Victoire Marie Louise Thérèse, daughter of King Louis XV) and K8 and K9 (those dedicated to the Countess of Tessè). We will speak more about the compositions published in Paris by Wolfgang (but composed in the previous months, not without the help of his father) after completing the information on the stay of the Mozarts in the French capital. In the meantime, Leopold figures out, and does not fail to highlight it to his interlocutors from Salzburg, the clamor he expects will provoke the Sonatas by his son, especially considering the age of the author.

Nor is he afraid that Wolfgang could be put in crisis by any public proofs of his abilities, proofs that had already been faced and overcome not only at the level of executive virtuosity (execution, sight reading, transposition into other tones, improvisation, etc. .) but also, according to what he says, at the level of composition when he was put to the test in writing a bass and the violin accompaniment of a minuet. Little Wolfgang's progress was so rapid that his father imagined that, upon returning to Salzburg, he could take up court service as a musician.

Nannerl also performs with precision the most difficult pieces that are submitted to her, but for her Leopold does not make grandiose projects: she is a woman and the prejudices of the time, fully shared by Leopold Mozart, make her at best a performer with prospects of living by giving lessons to the offspring of wealthy Salzburg families.

In the letter of February 22, Leopold Mozart announces the death of Countess van Eyck to Hagenauer, who had been hosting the whole family in her palace for months (no one bothered to prick the soles of her feet to make sure she was really dead, Leopold notes) and the disease that had affected Wolfgang: a sore throat with a cold so strong that it caused inflammation, high fever and the production of pleghm that he was not completely able expel.

The death of the Countess forced the Mozarts to look for a new place to live and Grimm found them an apartment in Rue de Luxembourg. On the occasion of little Wolfgang's illness we discover one of Leopold Mozart's characteristics, namely his competence (empirical but also based on reading and experience) in the medical field. In the correspondence, in this case as on other occasions, we find the treatments that he himself administered to family members on the basis of personal diagnoses or, for the most serious cases, on the indications of the doctors consulted.

First he made Wolfgang get out of bed and walked him back and forth around the room while, to bring down the fever, he repeatedly administered small doses of Pulvis antispasmodicus Hallensis (Halle's antispasmodic powder). This medicine, which took its name from the German city of Halle (in Saxony, near Leipzig), was based on Assa fetida (a resin of Persian origin), Castoreum of Russia (glandular secretion produced by the beaver in the period of the "scrub", sold at a high price so that it was often falsified or replaced by the less precious one imported from Canada), valerian (a plant rich in flavonoids still used today to promote sleep and reduce anxious phenomena), purple digitalis (plant containing active ingredients with effects on decompensation heart), sweet mercury (85% mercury oxide and 15% muriatic acid) and sugar. That concoction, whether it was effective or not, certainly did not kill the boy and probably helped Wolfgang to recover within four days.

For safety, however, Leopold, who cared obsessively about his son's health (an illness would have put projects and earnings at risk and the four days of forced rest, he calculated that they could have earned an extra 12 Louis of gold), also consulted a German friend, a certain Herrenschwand, doctor of the Swiss Guards who protected the King at Versailles.

Because the medicus only showed up twice to visit Wolfgang (Leopold writes it as if his doctor friend had neglected his duties, but evidently the disease was not so serious as to require daily visits) he thought it best to integrate the treatments with a some Aqua laxativa Viennensis (Viennese laxative water), a popular medicine certainly less dangerous as it is composed of Senna (Plant of Indian origin with laxative effects), Manna (extracted from the sap of the ash, with emollient and expectorant properties, slightly laxative), Creme of tartar (tartaric acid with natural leavening properties) mixed in six parts water.

Medicine in the 18th century

Mortality in the second half of the 18th century in European cities was four times higher than today. Vienna, with a population of around 270,000, had a death rate of 43 per thousand. The main reason was the large number of diseases present at the time, such as smallpox, typhus, scarlet fever and, in children, diarrhea. In addition, chronic infections such as tuberculosis and syphilis increased the death toll.

Life expectancy in the second half of the 18th century, especially in cities, was 32 years. The main reason was the high infant mortality rate. In the years 1762 to 1776, the average mortality rate of children under the age of two was 49% and at least 62% of children died within the fifth year. The main cause was diarrhea due to poor hygiene and inadequate infantile nutrition. Breastfeeding by mothers was not popular, so middle and upper-class women resorted to nurses for their children, who belonged to the lower classes and, often, were themselves carriers of disease.

Another method used was baby food, consisting of bread boiled in water or beer with the addition of sugar.

Wolfgang Mozart possessed erroneous notions about it, as evidenced by a letter written to his father in June 1783 on the occasion of the birth of his first child, Raimund Leopold, in which it is highlighted that he was against breastfeeding. He would have liked the baby to be fed only baby food, as it was for him and his sister.

Fortunately he gave in to the insistence of his mother-in-law and the son was entrusted to the care of a nurse even if, unfortunately, it was ineffective, and the baby lived only four weeks.

The therapies used at the time were poorly effective.

Gradually the notions deriving from medieval medicine were discarded, but in their place there were few alternatives.

For example, quinine in the form of Peruvian bark was used against malaria; opium was the only known analgesic, while mercury was used against syphilis.

Furthermore, the theory of mood disorder of the disease was still in vogue, which provided the removal of body fluids in order to expel bad moods and thus restore balance.

Therefore emetics, laxatives, enemas and bloodletting were widely used.

During the 18th century, medical techniques were used that today make us laugh, such as "tobacco smoke enemas", which were practiced in particular to reanimate drowned people (in London, but also in Venice, along the river or canals, in the apothecaries rather than in the parishes, at the piers and harbors, boxes with the equipment necessary to practice this therapy, just as is the case today for the defibrillators used in the case of cardiac arrest).

Leopold Mozart was probably always interested in medical treatments, the newest remedies and, more generally, scientific news, becoming aware of them during his long stay in London during the European Grand Tour.

Given the scarcity of official medicine results, "do-it-yourself" remedies were widely used, and as we have seen, the Mozart family was by no means exempt.

Here is a table of the most used medicines at the time:

- margravia powder (magnesium carbonate, mistletoe, etc.). Originally produced by the Berlin chemist Andreas Margraff (1709-1782);

- black powder, also called Pulvis Epilepticus Niger (seeds of croton, scammonea, peony, animal products, etc.). By far the most used remedy as it contained strong laxatives. It was used against epilepsy and also contained dried ground worms;

- scabiosa tea;

- rhubarb root;

- elderberry tea;

- white ointment (lard, white lead);

- anti gout pills (cooked seaweed or sponge)

Despite the approximation of many diagnoses and related treatments, we must not underestimate the evolution that the rationalistic thought of the 1700s allowed for the development of medical science which, thanks to the experimental method, made great strides forward and paved the way for subsequent progress.

Precisely in the 18th century, especially from the second half, the practice of medicine began to take on the modern characteristics as we know them today.

Characters such as Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771) founder of pathological anatomy, Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794) founder of modern chemistry, Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1799) scientist with many interests who was defined by Pasteur as "the greatest scientist who ever lived", Georges Buffon (1707-1788) the greatest naturalist of his time, Edward Jenner (1749-1823) discoverer of the smallpox vaccine, etc.

The development of medical science is accompanied by the transformation of hospitals from places of segregation of the sick, infamous prisons with very high mortality rates, to health care institutions where, albeit with extreme slowness, increasingly more hygiene and care systems were effectively making their way.

Bedside medicine (in which for centuries the medicus went to the patient's home to administer more or less effective treatments) was gradually replaced by hospital medicine along with consequent changes in the doctor-patient relationship.

The Austrian Emperor Joseph II in 1784, the year in which Wolfgang Mozart lived in Vienna reaping success and glory everywhere, promoted the foundation of the Allgemeines Krankenhaus (General Hospital).

However, the evolution of medical science did not prevent people, such as Leopold Mozart, from continuing to make use of traditional and commonly used self-care practices for a long time, the so-called "doctorless medicine" (diet, bloodletting, purge, ointments more or less dangerous to health, recipes taken from printed booklets, etc.) and characters not always prepared, such as apothecaries, surgeons and barbers continued to perform functions related to health, not to mention the charlatans who peddled concoctions of all kinds as miraculous solutions to all evil.

How can we not cite here a symbol of the charlatans of every era Doctor Dulcamara who, in Donizetti's "Elisir d'amore" staged in 1832, sold flasks of Bordeaux wine as a general remedy in the air "Hear, hear, rustic folk": Benefactor of men, repairer of evils, in a few days I will clear out, I will sweep the hospitals, and I want to sell health for the whole world. Buy it, buy it, I'll give it to you for cheap. This is the marvelous odontalgic liqueur, of mice and mighty destroying bugs, whose authentic certificates, stamped to be seen and read by each one I will do. For this specific, likeable mirifico of mine, a septuagenarian and valetudinary man, grandfather of ten children I am still to become.

For this reason Touch and Heal in a short week more than one afflicted young man ceased to cry. Or you, stiff matrons, do you yearn to rejuvenate? Your wrinkles uncomfortable with it erased. Do you, damsels, want to have smooth skin? You, gallant young people, forever have lovers? Buy my specific cure, I'll give it to you for a little while. It moves the paralytics, dispatches the apopletics, the asthmatics, the asphyxiates, the hysterics, the diabetics, heals tympanitides, scrofula and rickets, and even the liver pain, which in fashion became. Buy my specific cure, I'll sell it cheap.

The fears for the health of Wolfgang (above all) and Nannerl prompted the parents to vow to have masses recited in Salzburg in case of recovery: 4 masses at the Shrine of Maria Plan (not far from Salzburg) and 1 mass at the altar of the Child Jesus in the Loretokirche that was in the city. The costs of the masses were then to be deducted from the Mozarts' account with Hagenauer. Among the novelties that Leopold tells the Salzburg correspondents there was also the practice of inoculating smallpox which, he says, he was repeatedly invited to do to his children. Inoculation or variolation was introduced in Europe in 1722 by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the English ambassador to Constantinople, who had seen it practiced in Turkey. She had her first child inoculated and the second was even publicly inoculated at the English Court, as a demonstration of the efficiency of the method.

The positive result caused the entire English Royal Family to undergo inoculation. In Paris it seems that at the time when the Mozarts were present in the city it was a rather widespread fashion, so much so that laws were promulgated which, except for special permits, prescribed their practice in the city (to avoid contagions) while in the countryside it was allowed. Inoculation was a form of defense against smallpox, at the time the most widespread infectious disease in Europe, and consisted in exposing the subject to a mild form of the disease which allowed, in case of positive success, to immunize him from the most common forms, serious and often fatal. The practice, however, had serious risks both for the person subjected to inoculation (he could get sick with the most severe form) and for those who spent time with him during the active phase of the disease.

The risk therefore, for the Mozarts was particularly serious both at the level of possible infections and loss of earnings due to the forced isolation to which the inoculated subject had to be subjected. The practice continued to be used until 1796 when the vaccine introduced by Edward Jenner gradually led to the eradication of the disease.

In Paris, in that autumn / winter 1764, it snowed only once and the climate remained mild, at least this is what Leopold Mozart reports in his letters comparing the temperatures of the French capital with the much colder ones in Germany. On the other hand, the humidity and the rains were frequent, so much so that a silk rain cover was indispensable, which, apparently, almost everyone carried in the bag when they left the house.

The waterproof rain cover and the umbrella

Leopold was certainly used to protecting himself from the rain by using, like everyone in Europe up to that time, hoods or cloaks, so much so that he considered the rain cover a recent invention.

The fashion of the rain cover (note Leopold's use of the French term derived from parapluie) was imported to Paris from England, a territory with known characteristics of rainfall. In reality, the history of the rain cover derives from that, very ancient, of the parasol.

What we commonly call umbrella, in fact, is derived from its name its original meaning: to make shade.

This object is witnessed in ancient times in China and Japan as an attribute of Emperors and Samurai and a symbol of power reserved for them, but we have evidence of its use also in ancient Egypt, in classical Greece and in Imperial Rome.

The ceremonial parasol was used as a symbol of power also by the Popes, first, and later also by the Venetian Doges (who asked the Roman Pontiff for authorization to use it, too).

In epochs closer to us it seems that the custom of the parasol was brought to France (like many other things, including ice cream) by Caterina de 'Medici, in the 1500s, at the time of her marriage to Henry II.

From France the use of the parasol spread to England where in the 18th century, considering the prevailing climate in that territory, it was decided to use it also as a rain cover.

The new fashion then returned to France, where it became commonplace among the wealthier classes.

The frequent and abundant rains also caused the Seine to flood to the point, says Leopold, that many areas of Paris near the river were impassable and a boat had to be used to cross the Place de la Gréve (the current Town Hall square). In the same letter of 22 February 1764, Leopold Mozart announces that he plans to go to Versailles within 14 days to present the Opera before Wolfgang, the 2 Sonatas for harpsichord with violin accompaniment K6 and K7 (dedicated to Victoire, second daughter of King Louis XV) and the second Opera, Le and 2 Sonatas for harpsichord with violin accompaniment K8 and K9 (dedicated to Madame de Tessé, lady-in-waiting at the Court and animator of a famous cultural salon in Paris).

In a letter dated March 4, 1764, Leopold Mozart wants to dispel the prejudice, evidently widespread among his fellow citizens, that the French could not stand the cold. On the contrary, he writes, given that in Paris, unlike elsewhere, the shops of the artisans (tailor, shoemaker, saddler, cutler, goldsmith, etc.) remained open throughout the winter.

Not only that: the shops were open to for viewing by all passers-by and are illuminated in the evening with numerous lamps or appliques fixed to the walls, if not a beautiful chandelier in the middle of the room. Lighting was necessary because, as Leopold is astonished, these Parisian shops remained open in the evening until 10pm, and food shops until 11pm. The women in the house use warmers that they keep under their feet, made up of wooden boxes covered with tin provided with holes from which the heat came out, inside which were placed bricks or embers red-hot in the fire. The cold certainly did not stop Parisians of both sexes from taking walks and showing off in the Tuileries gardens, at the Palais-Royal or on the boulevards. In March, Leopold receives news from Salzburg: the court organist Adlgasser had been financed by the Archbishop to go to Italy to study the musical style that was so successful in Europe.

Leopold had certainly already thought that such an experience would also be necessary for little Wolfgang but this news probably confirmed his idea that the Archbishop, as he had done for Adlgasser (and for other Salzburg musicians, such as the singer Maria Anna Fesemayer on leave to study in Venice) would have financed at least part of the trip and allowed him to abstain again from the duties of his musical role at Court. On 3 March 1764, the Mozarts "lost" (much to the chagrin of the little Wolfgang of whom he was very fond) Sebastian Winter, the servant who had accompanied them from Salzburg for the whole journey to Paris. In fact, he had found a way to enter the service of Prince von Furstenberg as a hairdresser and left Paris to go to Donaueschingen where the Furstenbergs had their residence (which can still be visited today together with the brewery of the same name). Of course, one could not stay in Paris and frequent the beautiful world without a personal hairdresser-waiter, so the Mozarts hastened to find a replacement, a certain Jean-Pierre Potevin, an Alsatian who, given his origins, spoke both German and French well. However, the new waiter had to be suitably dressed, hence new expenses of which Leopold complains.

Providing some information especially addressed to Mrs. Hagenauer, Leopold Mozart takes the opportunity to display all of his opposition (perhaps a little underlined to highlight the sobriety of his ideas and of his modus vivendi) regarding French customs. Meanwhile, for Leopold, the French love only what pleased them and abhorred any kind of renunciation or sacrifice; in the poor times you could not find food that respected the precepts of the Catholic Church and the Mozarts, who ate in inns, were forced to break the ban by eating meat broth or spending a lot on fish dishes, which were very expensive. Fasting was not practiced by Parisians and Leopold, ironically, was anxious to ask for an official dispensation that allows his conscience to be calm while not respecting Catholic prescriptions relating to food.

Even the customs in religious practices are different than in Salzburg: no one in Paris used the rosary in church and the Mozarts are forced to use it hiding it inside the fur muffs that keep their hands warm, so as not to be subjected to curious or annoyed glances. The beautiful churches were few but on the other hand the noble palaces abound that highlight luxury and wealth. Even the carriages are symbols of extreme luxury, completely lacquered in laque Martin (the same one we have seen used for the snuffboxes) and embellished with paintings that would not disfigure in the best picture galleries. In the period of Lent then, unlike the German traditions that provide for the suspension of shows and dances, in Paris the period of reflection and penance is interrupted by inventing the "Ball of the virgins" also known as the "Carnival of the virgins". And here Leopold Mozart makes it clear what he thinks of the morality of the French.

Sex in France and Europe at the time of the Mozarts

While the concept was gaining ground that sexual pleasure was not the exclusive prerogative of man, but must also fall within the female sphere, erotic activity (both literary and practical) spread like wildfire and without the moral restraints that in the past was relegated to the secret of the bridal bed.

Of course, moral rules and laws still condemned promiscuity and prostitution was punished. In Vienna for example, by forcing the guilty girls (the poor ones, of course) to clean the city streets of horse excrement.

Love and sex are talked about and practiced throughout Europe but especially in Paris and Venice, the only city that, despite the ongoing decline of its power, could compete for the "dolce vita" with the French capital.

The search for pleasure as an end to itself became, first in the aristocratic world, but soon also in the bourgeois sections of the population, a way of thinking and living that for some even became an obsession.

To love, even outside of marriage (with discretion but without false modesty) became normal, as well as leaving without too many sorrows in view of a new "game" that led to other conquests.

Sex became an experience, for men and women (despite the permanent situation of social minority with respect to man), an achievement to be enumerated and cataloged (think of Mozart's Don Giovanni and his catalog, the perfect representative of that world that was about to disappear end of the century).

The 18th century is the century of seducers and libertines: Casanova (who in his biography lists 147 conquests) and the Marquis de Sade are perhaps the champions, and such have remained in the collective imagination.

The nobles, however, had to begin to suffer from the competition of new "objects of desire": the artists. In a historical moment that, if it does not invent the star-system at least consolidates it, actors and actresses, singers and dancers represent the "forbidden fruit" that attracted the desires of husbands and wives, eager to try new thrills.

However, it was always a question of whims and desires that were exhausted in the time span of a strong but not lasting passion fire or in menage in which the rich party financed the lover by offering a standard of living that could be "respectable".

Artists were rarely considered worthy to officially enter the blue blood pedigree.

Sex, in the century of the Mozarts, could be pure pleasure or a means for the conquest of money, power and positions kindly favored by those who, man or woman, have pleasantly enjoyed the relationship.

Certainly neither Leopold nor Wolfgang belonged to the category of careerists between the sheets: the marriage of the former was happy but certainly did not give him wealth or social advancements, that of the latter then, with the insipid Constanze (imposed on him by the crafty Mrs. Weber, who had finally managed to place even the least attractive of the three daughters) it was an obligatory choice.

As for dissolute conduct, on the other hand, Amadeus was not one to hold back, at least from the moment he found himself at his disposal far from his father's control. The affair with his cousin and the Viennese adventures with students and actresses of his plays are part of the often obscured story of his life.

In the 18th century the rich and powerful enjoyed, even in a non-figurative sense, their position of power which allowed them to dispense money and offices to their lovers; the latter having no problem moving from bed to tax collector's office or royal official.

If you were male you made a career for yourself, if you were female you used the influence obtained between the sheets to consolidate your role and to help relatives and friends by supporting their requests.

A single example, which circulated in Parisian salons at the time of Louis XV, can be illuminating. A Countess, who had already given up her arms in a singular encounter with the King, wrote him a letter (found by the monarch's servant by chance and delivered to Madame de Pompadour, the official lover) in which she asked him for 50,000 crowns, the command of a regiment for a relative of his, a bishopric for another relative ... and the liquidation of the Pompadour (which he evidently aspired to replace).

The wealthy aristocrats, when they were an "unfulfilled desire" for some girls and did not want to waste time intervening directly in the seductive game, hired a trusted valet, acting as a pimp, who lent himself to act as an intermediary and organize meetings (sometimes personally exploiting that particular role of power towards the bridesmaids, who did not refuse for fear of missing the greatest opportunity).

The practice of having lovers, moreover, came from high above. Louis XIV, the Sun King, had a disproportionate number of lovers of which about thirty "officers"; his successor Philip d'Orleans (regent until the coming of age of the future Louis XV) had two official lovers who worked simultaneously and without jealousy or reciprocal inhibition or for the countless meteors that quickly passed between the curtains of the royal bridal bed; Louis XV could count on about fifteen recognized lovers, plus the passing ones. And don't think that the High Clergy did no less.

For Carnival in every corner of the city there were dances, often with just a couple of musicians playing, according to Leopold, old out-of-date minuets. Approaching the time of departure for London Leopold is also thinking of relieving part of the gifts and purchases made in the previous stages of the journey by sending them to Salzburg and at the same time avoiding possible thefts or breakages due to the next loads and unloadings from the carriage with relative move to the inns.

A novelty that caused a sensation on Leopold were the so-called "English toilets" which in Paris were present in every private aristocratic palace. These are actually the first bidet models, equipped with cold and hot water sprayed upwards, which Leopold describes very briefly, not wanting to use inelegant terms. Even the bathrooms of the noble palaces are luxurious, with walls and floors in majolica, marble or even alabaster, equipped with porcelain chamber pots with gilded rims and jars with scented water and fragrant herbs.

Personal hygiene and bodily needs

We have previously seen how the use of terms related to bodily functions and the parts of the body involved was common in the Mozart family, in particular in the habits of Wolfgang and his mother.

But it is nothing to be shocked by!

At the time in Salzburg, but also in the rest of Europe, if we exclude the aristocracy (who lingered a little longer in the language to respect the alleged superiority over the lower classes) the use of trivial language was common.

After all, the habit with the natural functions of the body was much more "public" than it is today.

The bathrooms were practically absent in the vast majority of houses, if we exclude the noble palaces, and the bodily functions were not hidden as today but quietly carried out wherever nature had made its needs felt.

How to consider defecation a vulgar activity to be hidden at the time of the Sun King (Louis XIV) when it was actually considered a privilege reserved for the highest degrees of the court nobility to attend the "lever du Roi", the awakening of the King, including him sitting on the "throne" (equipped with a majolica vase and a table for reading and writing) that the sovereign used every morning to carry out his bodily needs?

And so, cascading from the King down, the activities of the body were considered natural and were carried out, if one was at home, in the chamber pot which was then emptied by throwing its contents out of the window.

The result of all this, added to the animal manure and the habit of throwing all kinds of garbage or processing waste on the street (there were no sewers or sanitation systems, except for some rare washing of the main and central streets of the cities ) was filthy streets and putrid cities.

If, on the other hand, you were out of the house, things got more complicated, not so much for the men who, thanks to the more practical clothes and the favorable physiology were able to find a secluded corner to relieve themselves, as well as for the women.

The aristocrats wore complex and overabundant dresses, with skirts, petticoats, bodices with strings and buttons, not to mention the "panier", a frame with concentric circles in wicker or whalebone, tied together by ribbons and fixed directly on the corset . How then?