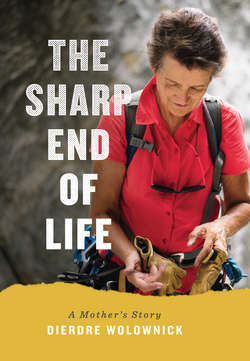

Читать книгу The Sharp End of Life - Dierdre Wolownick - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

one

ОглавлениеAN OCEAN OF ROCK. That’s what my son calls this monster wall of smooth granite that stretches toward the sky for three thousand feet, so high I can’t see the top from the base of the route we’re about to climb. I lean back so far my neck creaks.

“It’s an ocean of rock, and you’re just a speck,” Alex has said in many media interviews. He’s climbed El Capitan, in Yosemite National Park, many times, with and without rope. Standing in its shadow, I can’t force my mind to comprehend what those words mean. I know he’s done it. I’ve seen pictures. But now, as I cower at the foot of this monster, the thought of someone up there without a rope, clinging to the wall without any protection, makes my innards clench and my heart race. To go up there with rope is still unimaginable to me. And yet, here we are.

To be fair, I’m not actually going to climb the granite. I will climb the wall, but mostly with my feet, not my hands; they’ll be pushing the jumars up the rope. Alex will lead, putting in protection as he goes, the way he always does when we climb together. But this time, I’ll ascend the rope he carries up.

I’ll use jumars, daisy chains, a Grigri, specialized gear I’ve been learning about all year, to keep me safely attached to the rope as I battle my way up it. And it will be a battle. I’ll push one set of hand gear up the rope, stand on its attached foot strap, and then thrust the other hand and foot gear up to meet it, essentially pushing and stepping my way up the rope. At sixty-six, I won’t exactly be climbing rock. A fine distinction, as I stand here debating whether to run out into the woods one more time before we start and throw up.

Something deep inside me insists on that distinction, needs it. Climbing the rock of El Cap—there are over a hundred routes—is what the young studs do. Alex and his friends, they run up routes that are impossibly hard the way I run to the store: a few hours or so, and they’re on their way back down.

Most climbers take a few days to inch their way up El Capitan, the most impressive, iconic rock wall in Yosemite. I can almost make out some of the climbers on the routes near ours. They’ll sleep on a portaledge hanging from a few pieces of gear stuck in the rock. They’ll eat and make coffee hanging on the wall, raving about the incredible vistas with their legs dangling over Yosemite Valley a thousand or so feet below. They’ll take a dump up there, into a little plastic poop tube. They’ll probably talk to their girlfriend or boyfriend, or maybe their grandmother, because the higher you get on the walls here in Yosemite, the better the cell reception is. Maybe they don’t know they’re just a tiny speck that we can’t quite see. Or maybe that’s comforting to them.

To me, not so much. Alex and I plan to do it all, up and down, in one day. That means we have to work harder, or at least faster, than the portaledge folks. We’ll probably come down in the dark. Here on the ground, my breathing comes in short spurts, although I draw it in as calmly and evenly as I can. I try to swallow, but whatever it is that’s stuck in my throat feels like it could easily come back up.

I wonder if those specks up there ever throw up. Do they do that in the poop tube?

He did try to warn me. And months ago I’d heard him muttering to his friends at other crags where I’d tagged along to practice: “I don’t think she’ll do it.” Climb El Cap, he meant. At my age. For Alex, it’s an advanced age he can’t even imagine. He probably didn’t think my old ears could hear him. He doubted I’d be strong enough. Capable enough. Brave enough. Whatever it was he thought I’d need enough of, he didn’t think I’d have it by now.

I hope he’s wrong. No, he has to be wrong. Because once we launch, once we’re off the ground and become two tiny specks on the wall, we can’t change our minds. Once we’ve gone up a few pitches, or rope lengths, the only way back down is to top out three thousand feet up.

Or by helicopter.

Breathe.

I’ve trained for this for seven months. Longer than I’d trained for my first marathon, back in my fifties. Almost as long as I’d carried each of my babies.

By the time I finish this ascent, the past will have been sloughed off against the rock, left in a valley that I will have put behind me, forever. It’s been a monumentally long struggle that could have had many different endings.

But this isn’t an ending. It’s a beginning.