Читать книгу Heroes for All Time - Dione Longley - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Men of Connecticut!

WAR BEGINS, SPRING 1861

“Men of Connecticut! to arms!!” thundered the Hartford Daily Courant on April 13, 1861.1

Splashed across the newspaper was the shocking news: The day before, the Confederate military had opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. Forty-three Confederate guns and mortars pounded Sumter until the Union commander surrendered the fort to the Southerners. With undeniable certainty, civil war had arrived.

Suddenly the Land of Steady Habits was anything but. Agitated and confused, people drew together to discuss the astounding events.

“Large groups were congregated upon the streets, and … the war was the all absorbing theme … In the conversation, heated and passionate, in which the crowds participated, there was but little to be heard except indignation at the outrage of the Southern Rebels. It was deep and earnest.”2

In the quiet town of Winchester, it wasn’t much different. “The bombardment of Fort Sumter flew over the telegraph wires on Saturday, April 14, 1861, and electrified the country,” wrote resident John Boyd. The Winsted Herald declared grimly, “Northern blood is up, and history, faster than the pen can write, is making.”3

But not everyone was astonished by the South’s attack. For months, Governor William Buckingham had vigilantly followed each development in the national conflict. After Abraham Lincoln’s election on November 6, 1860, South Carolina had moved to secede. Six other states had quickly followed. When Southerners fired upon an unarmed ship bringing troops and supplies to Fort Sumter on January 9, 1861, Buckingham had quietly directed his state quartermaster to order equipment for 5,000 troops, and advised militia units around the state to fill their ranks and stand ready.

Just days before Fort Sumter fell, members of the Governor’s Foot Guard assembled at the state armory. Before long, many of the men—like George Haskell—would lay aside their ceremonial Foot Guard uniforms to don the utilitarian blue wool of the Union army.

An impassioned early broadside proclaimed, “Your country is in danger!” and urged Connecticut men to “drill, drill with such muskets as are at hand” in preparation for war.

Buckingham’s forethought was providential: on April 15, President Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to suppress the rebellion. The governor turned to his citizens and asked for a regiment of volunteers. Would Connecticut respond?

FOR OR AGAINST

“You must be counted for or against the government: which shall it be?” the Hartford Daily Courant demanded. “Descendants of those who marched under the banner of George Washington, which shall it be? … Sons of the old Charter Oak State, on which side do you enlist?”4

The answer came swiftly, from virtually every community in the state. Men crowded into hastily called meetings in town halls, assembly rooms, and churches. In Hartford, “men of all parties met, buried in a common grave all differences of opinion, and stood up as one man, brave, earnest, and steady for the contest. There was no faltering voice.”5

Men gave passionate speeches, calling for volunteers to defend the nation. George Burnham, a clerk, “said that if he had been so mean and despicable as to hesitate about his duty to his country’s flag, he could not have hesitated longer after seeing the brave, determined men before him … what he could do, he would do, and with his whole heart.”6

The dispute between North and South, and between Republicans and Democrats, was many years in the making. In 1859, John Brown, a deeply religious native of Torrington, Connecticut, brought the situation to a boiling point. A radical abolitionist, Brown advocated violence against slaveholders. He and twenty-one followers tried to initiate a slave rebellion, seizing a Federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, with the aim of arming slaves and abolitionists to fight for freedom. The plan failed. Captured and convicted of treason, an unrepentant Brown was executed on December 2, 1859. Brown’s plot outraged and frightened Southerners, and fueled the antagonism of Democrats everywhere. Slavery was now the issue dividing the nation, and the Republicans and Democrats squared off.

Farmers, teachers, factory workers and college students jumped to their feet and cried, “I’ll go!” At a meeting in Brooklyn, Connecticut, a town of perhaps 2,000 people, 60 men enlisted in the space of half an hour.7 John Boyd, the secretary of the state, enrolled in the 3rd Regiment—at the age of sixty-two.

“O! Pa. you do not know what enthusiasm, what patriotism, there is here among all classes,” a New Haven woman wrote excitedly to her father. “Party distinctions are not named, every body is for our country and the right. Not only the American born but the Irish and the Germans [immigrants] are ready to take up arms in our common defense.”8

WIDE AWAKE

The spirited support for the Union had emerged in Connecticut more than a year earlier, in February of 1860, sparked by the enthusiasm of a group of young Republican men in Hartford.

A group of Northerners had formed the Republican Party in 1854 to fight the spread of slavery into the nation’s western territories. Steadily, the Republicans gained support in the Northern states and began to challenge the long-established Democratic Party, which supported the extension of slavery.

In early 1860, Connecticut’s gubernatorial race was in full swing. Thomas H. Seymour, a pro-South Democrat, faced Republican governor William Buckingham, who strongly opposed the expansion of slavery. Connecticut’s election for governor was viewed as a bellwether for the upcoming presidential election.

“It is the commencement of the contest between free and slave labor,” announced the Hartford Daily Courant, adding that “a vote this spring in Connecticut for Thomas H. Seymour, is a vote for slave labor in the territories. Laboring men—young men of enterprise and muscle—you are interested in this decision! … Shall the territories become plantation of negroes?—or shall they be the homes of … every man following his own plow, on his own soil, working for his own family?”9

The young men that the Courant addressed were not asleep. Daniel Francis, twenty-four, and Edgar Yergason, nineteen, were clerks in a dry-goods store in Hartford. In February of 1860, the two attended a meeting of Hartford Republicans, which closed with an enthusiastic torchlight parade. Several hundred men lined up and lit kerosene torches, only to find that many were leaking. Just a few steps away was the store where Francis and Yergason worked; they hurried in and emerged with lengths of inexpensive black fabric which they and a few others tied around their necks like capes to protect their clothing from the kerosene. The capes gave the men a military look, and the procession’s organizer put them at the head of parade.

A few days later, Dan Francis, Ed Yergason, and thirty-four other young working men formed a Republican club. The group would promote the election of Republican candidates, beginning with William Buckingham. The members decided their organization would assume a military air: they would wear dark capes and caps as they escorted Republican speakers, kept order at political rallies, and generated enthusiasm for the upcoming elections. Francis, Yergason, and the others might as well have slapped the Democrats in the face with their gloves—the challenge was clear.10

Several weeks earlier, the Republican state convention’s chairman had spoken of the party’s “wide-awake spirit.”11 Now the young men took up the phrase for their club: they became the Wide Awakes. For decades, political questions had been decided by older, established men; now, suddenly, the young men found they had a voice.

THE RAIL-SPLITTER ARRIVES

The club’s inception could not have come at a better time. Just a week before, Abraham Lincoln had come east. In New York, 1,500 people came to hear what the ungainly Illinois lawyer had to say about the issue facing the nation. Deftly, Lincoln showed that America’s founders had expected to regulate slavery. President Washington had signed a bill modifying slavery, and a majority of the signers of the Constitution voted in Congress to limit slavery.

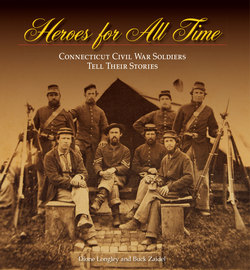

Members of Hartford’s Wide Awakes, with their distinctive capes and swinging lanterns, posed for a historic portrait in 1860. In just a few short months, the group of young Republican men from Connecticut would create an astonishing impact on the presidential election.

As he drew to a close after more than an hour, he urged quietly, “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”12 The audience exploded into cheers.

The next day Lincoln’s speech graced the front page of the New York Times, and suddenly his name was everywhere. Republican leaders in Connecticut invited him to speak. On March 5, he faced a large and curious audience at Hartford’s City Hall. Lincoln got right to the point: “Whether we will have it so or not, the slave question is the prevailing question before the nation.”

As he often did, Lincoln drew his listeners in with stories and metaphors.

Suppose, he said, he found a rattlesnake out in the field. “I take a stake and kill him. Everybody would applaud the act and say I did right. But suppose the snake was in a bed where children were sleeping. Would I do right to strike him there? I might hurt the children; or I might not kill, but only arouse and exasperate the snake, and he might bite the children … Slavery is like this.” Getting rid of the rattlesnake, he cautioned, took careful preparation.13

In New Haven the following evening, Lincoln met with “the wildest scene of enthusiasm and excitement.”14 But his next appearance was to be the blockbuster. In spite of rain, sleet, and the resulting mud, the streets of Meriden were thronged with people. When Lincoln’s train arrived, the crush at the station included Wide Awakes, several bands, and thousands of citizens who marched along with the speaker’s carriage to the hall. As an estimated 3,000 people crammed in, with hundreds more standing outside the open doors, Lincoln held the crowd spellbound.15

Lincoln’s visit left Connecticut Republicans primed for the turbulent campaigns. Around the state, young men immediately launched more Wide Awake chapters. As the gubernatorial election approached, the Wide Awakes rallied for Republican William Buckingham. The Democrats, just as tenacious, assailed Republican rallies and parades, hurling derision and rocks. On April 2, over 88,000 Connecticut voters cast their ballots. Buckingham won by 541 votes. The Wide Awakes breathed a collective sigh of relief.

WIDE AWAKE FOR LINCOLN

Six weeks later, the nation’s Republican convention chose Abraham Lincoln as its presidential nominee. “Momentum” can’t begin to describe the energy that the Wide Awakes now spread. All over the North and West, from Maine to California, hundreds of Wide Awake chapters sprang up and filled with members. In bigger cities, Wide Awakes filled car after car on special trains that brought them to rallies with other clubs.

Getting Lincoln into office promised to be a vicious battle. “Wherever the fight is hottest, there is their post of duty, and there the Wide Awakes are found,” declared the Hartford group in a circular it sent to other chapters.16

The day after Lincoln’s victory, the Hartford Times—a Democratic newspaper—predicted that the states that allowed slavery would “form a separate confederacy, and retire peaceably from the Union … We can never force sovereign States to remain in the Union when they desire to go out, without bringing upon our country the shocking evils of civil war, under which the Republic could not, of course, long exist.”17

Democrats were bitter. Many would nurse their resentment against Lincoln, the Republicans, and abolitionists for years.

The Hartford Evening Press, November 7, 1860.

Daniel Gould Francis, a Hartford dry-goods clerk, helped found the Wide Awakes in March of 1860. When war broke out, Francis was one of the earliest to enlist, joining Connecticut’s 1st Regiment.

Females couldn’t enlist in the military, but that didn’t stop them from holding strong political opinions. This unidentified woman had her portrait taken in May of 1861, perhaps to give to a departing soldier. Like many civilians in the early weeks of the war, she donned a red, white, and blue ribbon that showed her loyalty—as did her inscription, “Union now and forever.”

The Wide Awakes, exultant in Lincoln’s victory, had little left to do. Their role in the presidential campaign had very possibly changed history.

It would be just a few months before Dan Francis and Ed Yergason put away their capes, donned the blue wool uniforms of Union infantry, and faced bullets instead of rocks as the fight moved from the political arena to the battlefield.

HELP FROM ALL QUARTERS

Now that war had arrived, those who couldn’t enlist found other ways to help. Factory owners promised to continue the salaries of employees who enlisted. Towns pledged to support their soldiers’ families: at a single meeting, Norwich citizens donated over $14,000.18 In Middletown, Dr. Baker proposed to treat soldiers’ families at no cost, and the photography team of Bundy and Williams promised free pictures of all the volunteers.19

Henry Schulze, a Hartford tailor, offered to cut out uniforms; other tailors throughout the state did the same. Thousands of Connecticut women joined them, sewing uniforms and haversacks in shifts, day and night.

Everywhere, Connecticut citizens showed their support for the Union. William North Rice, a Wesleyan student, described the scene in Middletown: “The war spirit is rampant here. About half the people one meets in the street wear union badges—cockades, neck-ties, pins, buttons, etc… . Flags are hung out from many of the houses.”20

“Already the national flag had come to have a new and strange significance,” asserted one Connecticut writer. “When the stars and stripes went down at Sumter, they went up in every county of our State.”21

EVERYTHING IS WARLIKE

As Connecticut scrambled to organize troops, Massachusetts’ 6th Regiment had already filled its ranks and was on its way south. When their train pulled into the Hartford station on April 18, the Massachusetts boys found 2,500 Connecticut people waiting—at two o’clock in the morning—with enthusiastic speeches, food, and rousing cheers.22

Dr. George Clary portrayed the mood in Hartford: “Everything is warlike, the streets, the dress of people, the papers, etc. The air resounds with the din of war and nothing else can be thought or talked of.”23

CONNECTICUT VOLUNTEERS

Now Connecticut moved forward, rapidly filling three regiments during April and May of 1861. A regiment (usually 800 to 1,000 men) was composed of about ten companies, each assigned a letter.

Horace Purdy joined Company E of the 1st Regiment. A twenty-six-year-old hatter, Horace was a member of the Wooster Guard, a volunteer militia unit in Danbury. As events unfolded, the Wooster Guard gathered with a sense of rising urgency. Horace jotted the proceedings in his diary: “Wednesday April 17th … Attended a special meeting of the Guards at our Hall in the eve at which we volunteered our services to the Governor (Buckingham) as volunteers in the U States service in answer to the Presidents call for 75,000 troops. There were a large number of spectators at the room and when we with one voice offered our services, a long loud shout went up from the people.”24

Across the state, other militia units did the same, each acting as the nucleus of a company of 75 to 100 soldiers. Most community militias had drilled together and marched in parades, but few had serious military training. As the Hartford Daily Courant put it, “The Hartford City Guard was not organized for the purpose of performing military duty … But the time has come when men are wanted to protect the government, and the Hartford City Guard have overthrown their character as holiday troops, and are putting themselves in condition for acceptance as volunteers.”25

Soldiers of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd regiments enlisted for only three months—a term so brief that it was hardly an impediment to the mostly young men who in a surge of patriotism had stepped forward to volunteer. Gustavus Dana, a toolmaker who enlisted in the 1st Regiment, noted: “the general opinion was that the trouble would be ended and that we would be home at the end of the three months.”26

A Charter Oak insignia marked the militia uniform of an unidentified Connecticut man. Militia units from New Haven, Middletown, Danbury, Waterbury, and a host of other communities enlisted in Connecticut’s first three Civil War regiments in April and May of 1861 and made up the core of early officers.

While the governor appointed the colonels who would lead the regiments, the captaincy of each company was usually awarded to the man who had actively recruited most of its soldiers. Daniel Klein, the son of a German immigrant, became a captain in the 3rd Regiment after he enlisted scores of men from New Haven’s German community, with names like Gustav Voltz, Caspar Zimmerman, and Otto Frankel.

As each company filled, its soldiers left for training camp: New Haven, for the 1st and 2nd Regiments; Hartford, for the 3rd Regiment. As they left their hometowns, the soldiers found themselves surrounded by well-wishers. A young tinworker from Middletown described his departure:

In the early weeks of the war, stores around Connecticut could barely keep up with the demand for American flags, cockades, flag pins, and red, white, and blue ties. Other hot sellers were firearms and blankets for the soldiers, and military tactics manuals.

As our company were taking the [railroad] cars to Hartford, the rendezvous of the Third regiment, a good, honest farmer, from the village in which I had been living, came along … There was a large crowd around the cars, so that he could not get to the door, but he edged his way up to my window, and reaching up his hand, said, “Pull me up, I want to see you.” … He hung onto the car window for half a minute, wishing me the best of luck and good wishes generally, and then shook hands with me and left. As he shook hands, he left a five dollar bill in my hand … there was something in this man’s style that showed he was sincere in what he said; that his heart was with his country in the hour of trouble, and that his heart and sympathies were with those that were going to fight for the country’s honor. He might have made a patriotic speech two hours long, and it would not have impressed me as favorably as that five dollar bill did.27

George Branch, a harness maker in Hartford, enlisted in Connecticut’s 1st Regiment on April 16. On the evening of April 19 he got married; the next morning, his regiment departed for camp.

Military fever struck the children as well, and boys like this one contributed to “the din of war,” many forming their own drum corps. This young drummer wore an improvised uniform based on the colorful Zouave style—baggy red pants, short jacket, and a fez or turban on the head—adapted from the uniform of the French Zouaves in the Crimean War, and popularized in America by Col. Elmer Ellsworth, whose Zouave drill team had toured and electrified the country in 1860.

Sgt. Andrew Knox, a housepainter in the 1st Regiment, left behind his nineteen-year-old bride, Sarah. In a letter from training camp, he tried to explain why: “it was as much as I could do to tear myself away from you but my country called and I must obey my duty. For the first time the proud flag of my country has been insulted and disgraced it must be avenged at any cost and now my dear wife be true to me and I may soon [be] back but if I fall on the field of battle remember … that I die in [a] good cause the cause which our fathers fought for and died for.”28

THE BEGINNING OF SOLDIER LIFE

Once in camp, training began in earnest. Most men found it difficult, if not impossible, to adjust immediately to army life. “Discontent amounting almost to mutiny in our Co on account of our rations,” noted a private in the New Haven training camp of the 1st Connecticut.29 A number of men ran the guard and headed into downtown New Haven for breakfast, earning a stern reprimand from their colonel.

But time was short. The Confederates could attack Washington at any time. Connecticut’s green troops had to rush to learn drills, tactics, and the army’s daily routine. Many volunteers had never handled a musket. Now they struggled to learn “load in nine times,” the intricate nine-step process to load and fire a single cartridge.

Many officers were as inexperienced as the enlisted men, and had to learn as they went along. They consulted their new copies of Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics for the Exercise and Manoeuvres of Troops When Acting as Light Infantry or Riflemen, more commonly called Hardee’s Tactics. The men of the 2nd Regiment, quartered in New Haven, swallowed their pride as boys at William Huntington Russell’s military academy taught them their drills.30

Boys at the Collegiate and Commercial Institute in New Haven—like this young drummer—had been learning military drills for years before the war began. Students there put the new soldiers of the 2nd Regiment through their paces, drumbeats keeping the marching soldiers in step. Some 300 of the Institute’s former students would go on to become commissioned officers in the Union army.

Connecticut issued 700 of these nonregulation blue-painted canteens to men in the 1st Regiment. The state quartermaster’s report described them as “canteen-ration boxes.” The upper half contained two compartments for liquids with brass spout caps marked “patent April 2 1861” by Meriden inventor James Breckenridge. A swinging latch hook held the top and bottom compartments together. (Patent and quartermaster information courtesy of Dean Nelson, Museum Administrator, Museum of Connecticut History, Hartford.)

But being a soldier had its advantages, too: they hadn’t yet left for the war, and they were already heroes. “O, it was a glorious thing to be a soldier in those days!” recalled one volunteer.

[F]or those seventy-five thousand soldiers that had enlisted and were actually going to the war there was nothing too good. During the few weeks of preparation for the seat of war while they were at their rendezvous in their native states, they were petted and feasted, and grasped warmly by the hand with a fervent “God bless you” by the older people; smiled upon and urged to accept all kinds of presents, such as needle cases, pin-cushions, handkerchiefs, havelocks, pictorial newspapers, tracts and bibles, by beautiful ladies and bright-eyed girls, or invited into hotels and saloons and “treated” by some of their old chums who hadn’t quite courage enough to go for soldiers themselves, but heartily admired those who had; admitted to theaters and other places of amusement with no other ticket than enough of their soldier’s uniform on to show who they were.31

When they’d finished their brief training, the time came to depart for Washington. A great many had never been outside of the state. Opening ahead of them was a world they knew nothing about. Each man wondered what the future would bring for him.

CONNECTICUT’S LYON

Nearly 1,000 miles from his home in Connecticut, Capt. Nathaniel Lyon, a West Point graduate and a twenty-year veteran of the regular army, recognized the strategic importance of the arsenal at St. Louis, Missouri. Outfoxing the Rebel opposition in April of 1861, he secured most of the arms in the arsenal, thereby preventing thousands of guns from falling into Confederate hands.

Hoping to avoid fighting within Missouri, conservatives from the state called a meeting between its Southern-leaning militias and officers of federal forces. When Confederate sympathizers proposed that each side should disband its military units and keep troops of both armies out of the state, the red-headed Lyon spat: “Rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any matter … I would see you … and every man, woman, and child in the State, dead and buried. This means War.”32

He meant it. After driving Confederate forces to the outskirts of Missouri, an outnumbered Lyon—now promoted to general—launched a bold attack at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on June 11. The assault worked initially, but fizzled after Lyon, waving his hat to encourage his men, was shot through the heart.

Known for his red hair and equally fiery personality, Nathaniel Lyon was the first general to give his life for the Union. As the procession carrying his coffin made its way through the night to his hometown of Easton, hundreds of citizens lined its route, lighting the way with candles, lanterns, and torches. Thousands of people (estimates range from 10,000 to 20,000) attended General Lyon’s funeral.

Joe Hawley, a thirty-four-year-old newspaper editor in Hartford, enlisted as soon as Governor Buckingham issued the call. He and two friends immediately began recruiting soldiers. Just twenty-six hours later, they had signed up an entire company (eighty-four men), with more waiting. Joe’s wife Harriet was as fiercely patriotic as her husband. Over and over she expressed her frustration at not being able to serve as the soldiers did. “I envy him,” she wrote of her husband. “I ain’t sure but that I wish I was his brother instead of his wife—or him instead of myself.” The Hawleys fervently opposed slavery, and their devotion to the Union cause was unshakeable. In the next four years, both of them were to offer their lives for it repeatedly. (Letter from Harriet Foote Hawley, June 18, 1864, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford.)

In Meriden, an eager twenty-one-year-old clerk in a dry-goods store took off his apron and signed his enlistment papers. Charles Upham began as a sergeant in Connecticut’s 3rd Regiment. By war’s end, he would wear a colonel’s silver eagles on his shoulder straps. He would also bear the marks of personal tragedy and a battle wound that would never heal.

In April 1861, Col. Joseph Mansfield waited tensely at his home in Middletown. A career army officer, the fifty-seven-year-old colonel had more than an inkling of what lay ahead.

His courage in battle during the Mexican War had earned him advances, but Mansfield was also highly respected for his skill and experience as an army engineer. He had supervised the construction of military forts across the West and the South—and at the same time, observed the nation’s gathering storm. Now orders summoned him to Washington: the capital lay open to attack. Thorough and methodical, Mansfield could be trusted to direct the city’s defenses. President Lincoln promoted him to brigadier general, commanding the Department of Washington. General Mansfield went to work immediately, creating a ring of forts that would protect the capital from every direction—but in his heart, he longed to lead troops into battle.

LEAVING HOME

For the Nutmeggers just finishing their training, the adventure was about to begin. Each regiment, before leaving the state, received its regimental colors in a solemn ceremony. On May 8, former lieutenant governor Julius Catlin spoke movingly to the 1st Regiment as he presented it with an American flag and a hand-painted silk regimental flag. “Take this flag to be your standard in the battle,” Catlin declared, “where blows fall thickest and the fight rages hottest, there may it float, and beneath it strike the strong arms and brave hearts of Connecticut. Remember whose children you are—whose honor you inherit.”33

With proud, jaunty airs, the men fell in behind the spotless flags. Onlookers cheered and bands played. Three months later, the flags would return bullet-ridden; the men beaten and shocked. The war, which that day looked to be brief and glorious, would drag on for years and affect every single person in Connecticut.