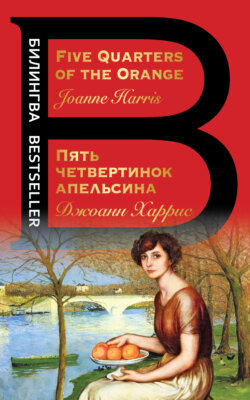

Читать книгу Five Quarters of the Orange / Пять четвертинок апельсина - Джоанн Харрис, Joanne Harris - Страница 14

Joanne Harris

Five Quarters of the Orange

Part Two

Forbidden fruit

5

ОглавлениеSoon after that, I found the lipstick under Reine-Claude’s mattress. A stupid place to hide it, really-anyone could have found it, even Mother-but Reinette was never imaginative. It was my turn to make the beds, and the thing must have worked its way under the bottom sheet, because that was where I found it, tucked between the lip of the mattress and the bedboard. At first I didn’t recognize it. Mother never used makeup. A small golden cylinder, like a stubby pen. I turned the cap, encountered resistance, opened. I was experimenting rather gingerly on my arm when I heard a gasp behind me and Reinette jerked me round. Her face was pale and contorted.

“Give me that!” she hissed. “That’s mine!”

She snatched the lipstick from my fingers and it fell to the floor, rolling under the bed. Quickly she scrabbled to retrieve it, her face flaring.

“Where did you get that?” I asked curiously. “Does Mother know you’ve got it?”

“None of your business,“ gasped Reinette, emerging from under the bed. ”You’ve no right to go snooping in my private things. And if you dare tell anyone-“

I grinned. “I might tell,” I told her. “And I might not. It just depends.”

She took a step forward, but I was almost as tall as she was, and though rage had made her reckless, she knew better than to try to fight me.

“Don’t tell,” she said in a wheedling voice. “I’ll go fishing with you this afternoon, if you like. We could go to the Lookout Post and read magazines.”

I shrugged. “Maybe. Where did you get it?”

Reinette looked at me.

“Promise you won’t tell.”

“I promise.”

I spat in my hand. After a moment’s hesitation she followed suit. We sealed the bargain with a spit-clammy handshake.

“All right.” She sat down on the edge of the bed, legs curled underneath her. “It was at school. In spring. We had a Latin teacher there, Monsieur Toubon. Cassis calls him Monsieur Toupet because he looks as if he wears a wig. He was always getting at us. He was the one who made the whole class stay in that time. Everybody hated him.”

“A teacher gave it to you?” I was incredulous.

“No, stupid. Listen. You know the Boches requisitioned the lower and middle corridors and the rooms around the courtyard. You know, for their quarters. And their drilling.”

I’d heard this before. The old school, with its location near the center of Angers, its large classrooms and enclosed playgrounds, was ideal for their purposes. Cassis had told us about the Germans on maneuvers with their gray cow’s-head masks, how no one was allowed to watch and the shutters had to be closed around the courtyard at those times.

“Some of us used to creep in and watch them through a slit under one of the shutters,” said Reinette. “It was boring, really. Just a lot of marching up and down and shouting in German. Can’t see why it all has to be so secret.” Her mouth drooped in a moue of dissatisfaction. “Anyway, old Toupet caught us at it one day,” she continued. “Gave us all a big lecture, Cassis and me and… oh, people you wouldn’t know. Made us miss our free Thursday afternoon. Gave us a whole lot of extra Latin to do.” Her mouth twisted viciously. “I don’t know what makes him so holy anyhow. He was only coming to watch the Boches himself.” Reinette shrugged. “Anyway”-she continued in a lighter voice-“we managed to get him back eventually. Old Toupet lives in the collège-he has rooms next to the boys’ dorm-and Cassis looked in one day when Toupet was out, and what do you think?”

I shrugged.

“He had a big radio in there, pushed under his bed. One of those long-wave contraptions.”

Reinette paused, looking suddenly uneasy.

“So?”

I looked at the little gold stick between her fingers, trying to see the connection.

She smiled, an unpleasantly adult smile.

“I know we’re not supposed to have anything to do with the Boches. But you can’t avoid people all the time,” she said in a superior tone. “I mean, you see them at the gate, or going into Angers to the pictures…”

This was aprivilege I greatly envied Reine-Claude and Cassis-that on Thursdays they were allowed to cycle into the town center to the cinema or the café-and I pulled a face.

“Get on with it,” I said.

“I am,” complained Reinette. “God, Boise, you’re so impatient…” She touched her hair. “As I was saying, you’re bound to see Germans some of the time. And they’re not all bad.” That smile again. “Some of them can be quite nice. Nicer than old Toupet, anyway.”

I shrugged indifferently.

“So one of them gave you the lipstick,” I said with scorn.

Such a fuss over so little, I thought to myself. It was just like Reinette to get so excited about nothing at all.

“We told them-well, we just mentioned to one of them-about Toupet and his radio,” she said. For some reason she was flushed, her cheeks bright as peonies. “He gave us the lipstick, and some cigarettes for Cassis, and… well, all kinds of things.” She was speaking rapidly now, unstoppably, her eyes bright. “And later Yvonne Cressonnet said that she saw them come to old Toupet’s room, and they took the radio away, and he went with them, and now instead of Latin we have an extra geography lesson with Madame Lambert, and no one knows what’s happened to him!”

She leveled her gaze at me. I remember her eyes were almost gold, the color of boiling sugar syrup as it begins to turn.

I shrugged. “I don’t suppose anything happened,” I said reasonably. “I mean, they wouldn’t send an old man like that to the front just for having a radio.”

“No. Course they wouldn’t.” Her reply was too hasty. “Besides, he shouldn’t have had it in the first place, should he?”

I agreed he shouldn’t. It was against the rules. A teacher should have known that. Reine looked at the lipstick, turning it gently, lovingly in her hand.

“You won’t tell, then?” She stroked my arm gently. “You won’t, will you, Boise?”

I pulled away, rubbing my arm automatically where she had touched me. I never did like being petted.

“Do you and Cassis see these Germans often?” I questioned.

She shrugged. “Sometimes.”

“D’you tell them anything else?”

“No.” She spoke too quickly. “We just talk. Look, Boise, you won’t tell anyone, will you?”

I smiled. “Well, I might not. Not if you do something for me.”

She looked at me narrowly.

“What do you mean?”

“I’d like to go into Angers sometimes, with you and Cassis,” I said slyly. “To the pictures, and the café, and stuff…”

I paused for effect and she glared at me from eyes as bright and narrow as knives.

“Or,” I continued in a falsely holy tone, “I might tell Mother that you’ve been talking to the people who killed our father. Talking to them and spying for them. Enemies of France. See what she says to that.”

Reinette looked agitated.

“Boise, you promised!”

I shook my head solemnly.

“That doesn’t count. It’s my patriotic duty.”

I must have sounded convincing. Reinette turned pale. And yet the words themselves meant nothing to me. I felt no real hostility to the Germans. Even when I told myself that they had killed my father, that the man who did it might even be there, actually there in Angers, an hour’s cycle ride down the road, drinking Gros-Plant in some bar-tabac and smoking a Gauloise. The image was clear in my mind, and yet it had little potency. Perhaps because my father’s face was already blurring in my memory. Perhaps in the same way that children rarely get involved in the quarrels of adults, and that adults rarely understand the sudden hostilities that erupt for no comprehensible reason between children. My voice was prim and disapproving, but what I really wanted had nothing to do with our father, France or the war. I wanted to be involved again, to be treated as an adult, a bearer of secrets. And I wanted to go to the cinema, to see Laurel and Hardy or Bela Lugosi or Humphrey Bogart, to sit in the flickering dark with Cassis on one side and Reine-Claude on the other, maybe with a cone of chips in one hand or a strip of licorice…

Reinette shook her head. “You’re crazy,” she said at last. “You know Mother would never let you go into town on your own. You’re too young. Besides-”

“I wouldn’t be on my own. You or Cassis could take me on the back of your bike,”

I continued stubbornly. She rode my mother’s bike. Cassis took Father’s bike to school with him, an awkward black gantrylike thing. It was too far to walk, and without the bikes they would have had to board at the collège, as many country children did.

“Term’s nearly over. We could all go into Angers together. See a film. Have a look round.”

My sister looked mulish.

“She’ll want us to stay home and work on the farm,” she said. “You’ll see. She never wants anyone to have any fun.”

“The number of times she’s been smelling oranges recently,” I told her practically, “I don’t suppose it will matter. We could sneak off. The way she is, she’ll never even know.”

It was easy. Reine was always easy to move. Her passivity was an adult thing, her sly, sweet nature hiding a kind of laziness, almost of indifference. She faced me now, throwing her last weak excuse at me like a handful of sand.

“You’re crazy!”

In those days everything I did was crazy to Reine. Crazy for swimming underwater, for teetering at the top of the Lookout Post on one leg, for answering back, for eating green figs or sour apples.

I shook my head.

“It’ll be easy,” I told her firmly. “You can count on me.”