Читать книгу Five Quarters of the Orange / Пять четвертинок апельсина - Джоанн Харрис, Joanne Harris - Страница 27

Joanne Harris

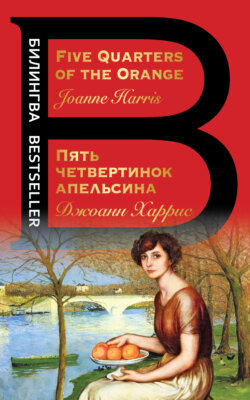

Five Quarters of the Orange

Part Three

The snack-wagon

1

ОглавлениеIt was maybe five months after Cassis died-four years after the Mamie Framboise business-that Yannick and Laure came back to Les Laveuses. It was summer, and my daughter Pistache was visiting with her two children, Prune and Ricot, and until then it was a happy time. The children were growing so fast and so sweet, just like their mother, Prune chocolate-eyed and curly-haired and Ricot tall and velvet-cheeked, and both of them so full of laughter and mischief that it almost breaks my heart to see them, it takes me back so. I swear I feel forty years younger every time they come, and that summer I taught them how to fish and bait traps and make caramel macaroons and green-fig jam, and Ricot and I read Robinson Crusoe and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea together, and I told Prune outrageous lies about the fish I’d caught, and we shivered at stories of Old Mother’s terrible gift.

“They used to say that if you caught her and set her free, she’d give you your heart’s desire, but if you saw her-even out of the corner of your eye-and didn’t catch her, something dreadful would happen to you.”

Prune looked at me with wide pansy-colored eyes, one thumb corked comfortingly in her mouth.

“What kind of a dreadful?” she whispered, awed.

I made my voice low and menacing.

“You’d die, sweetheart,” I told her softly. “Or someone else would. Someone you loved. Or something worse even than that. And in any case, even if you survived, Old Mother’s curse would follow you to the grave.”

Pistache gave me a quelling look.

“Maman, I don’t know why you want to go telling her that kind of thing,” she said reproachfully. “You want her to have nightmares and wet the bed?”

“I don’t wet the bed!” protested Prune. She looked at me expectantly, tugging at my hand. “Mémée, did you ever see Old Mother? Did you? Did you?”

Suddenly I felt cold, wishing I had told her another story. Pistache gave me a sharp look and made as if to lift Prune off my knee.

“Prunette, you just leave Mémée, alone now. It’s nearly bedtime, and you haven’t even brushed your teeth or-”

“Please, Mémée, did you? Did you see her?”

I hugged my granddaughter, and the coldness receded a little.

“Sweetheart, I fished for her during one entire summer. All that time I tried to catch her, with nets and line and pots and traps. I fixed them every day, checked them twice a day and more if I could.”

Prune looked at me with solemn eyes.

“You must really have wanted that wish, him?”

I nodded. “I suppose I must have.”

“And did you catch her?”

Her face glowed like a peony. She smelt of biscuit and cut grass, the wonderful warm, sweet scent of youth. Old people need to have youth about them, you know, to remember.

I smiled. “I did catch her.”

Her eyes were wide with excitement. She dropped her voice to a whisper.

“And what did you wish?”

“I didn’t make a wish, sweetheart,” I told her quietly.

“You mean she got away?”

I shook my head.

“No, I caught her all right.”

Pistache was watching me now, her face in shadow. Prune put her small plump hands on my face. Impatiently:

“What then?”

I looked at her for a moment.

“I didn’t throw her back,” I told her. “I caught her at last, but I didn’t let her go.”

Except that wasn’t quite right, I told myself then. Not quite true. And then I kissed my granddaughter and told her I’d tell her the rest later, that I didn’t know why I was telling her a load of old fishing stories anyway, and in spite of her protests, between coaxing and nonsense, we finally got her to bed. I thought about it that night, long after the others were asleep. I never had much trouble sleeping, but this time it seemed like hours before I could find any peace, and even then I dreamed of Old Mother down in the black water, and myself pulling, pulled, pulling, as if neither of us could bear ever to let go…

Anyway, it was soon after that they came. To the restaurant to begin with, almost humbly, like ordinary customers. They had the brochet angevin and the tourteau fromage. I watched them covertly from my post in the kitchen, but they behaved well and caused no trouble. They spoke to each other in low voices, made no unreasonable demands on the wine cellar, and for once refrained from calling me Mamie. Laure was charming, Yannick hearty; both were eager to please and to be pleased. I was somewhat relieved to see that they no longer touched and kissed each other so often in public, and I even unbent enough to talk to them for a while over coffee and petits fours.

Laure had aged in four years. She had lost weight-it may be the fashion, but it didn’t suit her at all-and her hair was a sleek copper helmet. She seemed edgy too, with a habit of rubbing her abdomen as if she had a pain there. As far as I could see, Yannick hadn’t changed at all.

The restaurant was doing well, he declared cheerfully. Plenty of money in the bank. They were planning a trip to the Bahamas in spring; they hadn’t had a holiday together in years. They spoke of Cassis with affection and-I thought-genuine regret.

I began to think I’d judged them too harshly.

I was wrong.

Later that week they called at the farm, when Pistache was about to put the children to bed. They brought presents for us all, sweets for Prune and Ricot, flowers for Pistache. My daughter looked at them with that expression of vacant sweetness which I know to be dislike, and which they no doubt took for stupidity. Laure watched the children with a curious insistence that I found unsettling; her eyes flicked constantly toward Prune, playing with some pine cones on the floor.

Yannick settled himself in an armchair by the fire. I was very conscious of Pistache sitting quietly nearby, and hoped my uninvited guests would leave soon. However, neither of them showed any desire to do so.

“The meal was simply wonderful,” said Yannick lazily. “That brochet-I don’t know what you did with it, but it was absolutely marvelous.”

“Sewage,” I told him pleasantly. “There’s so much of it pours into the river nowadays that the fish practically feed on nothing but. Loire caviar, we call it. Very rich in minerals.”

Laure looked at me, startled. Then Yannick gave his little laugh-hé, hé, hé-and she joined him.

“Mamie likes her joke, hé, hé. Loire caviar. You really are a tease, darling.”

But I noticed they never ordered pike again.

When Pistache had put the children to bed, Yannick and Laure began to talk about Cassis. Harmless stuff at first-how Papa would have loved to see his niece and her children.

“He was always saying how much he wanted us to have children,” said Yannick. “But at that stage in Laure’s career-”

Laure interrupted him.

“There’ll be plenty of time for that,” she said, almost harshly. “I’m not so old, am I?”

I shook my head.

“Of course not.”

“And of course, at that time there was the added expense of looking after Papa to think about. He had hardly anything left, Mamie,” said Yannick, biting into one of my sablés. “All he had came from us. Even his house.”

I could believe it. Cassis was never one to hoard wealth. He slid it through his fingers in smoke, or more often into his belly. Cassis was always his own best customer in the Paris days.

“Of course we wouldn’t think of begrudging him that.” Laure’s voice was soft. “We were very fond of poor Papa, weren’t we, chéri?”

Yannick nodded with more enthusiasm than sincerity.

“Oh, yes. Very fond. And of course… such a generous man. Never felt any resentment at all about… this house, or the inheritance, or anything. Extraordinary.”

He glanced at me then, a sharp ratty slice of a look.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

I was up at once, almost spilling my coffee, still very conscious of Pistache sitting next to me, listening. I had never told my daughters about Reinette or Cassis. They never met. As far as they knew I was an only child. And I had never spoken a word about my mother.

Yannick looked sheepish.

“Well, Mamie, you know he was really supposed to inherit the house-”

“Not that we blame you-”

“But he was the eldest, and under your mother’s will-”

“Now wait a minute!” I tried to keep the shrillness from my voice but for a moment I sounded just like my mother, and I saw Pistache wince. “I paid Cassis good money for this house,” I said in a lower tone. “It was only a shell after the fire, anyway, all burnt out with the rafters poking through the slates. He could never have lived in it, wouldn’t have wanted to either. I paid good money, more than I could afford, and-”

“Shh. It’s all right.” Laure glared at her husband. “No one’s suggesting your agreement was in any way improper.”

Improper.

That’s a Laure word all right, plummy, self-satisfied and with just the right amount of skepticism. I could feel my hand tightening around the rim of my coffee cup, printing bright little points of burn on my fingertips.

“But you have to see it from our point of view.” That was Yannick, his broad face gleaming. “Our grandmother’s legacy…”

I didn’t like the way the conversation was heading. I especially hated Pistache’s presence, her round eyes taking everything in.

“You never even knew my mother, any of you,” I interrupted harshly.

“That’s not the point, Mamie,” said Yannick quickly. “The point is that there were three of you. And the legacy was divided into three. That’s right, isn’t it?”

I nodded cautiously.

“But now since poor Papa has passed away, we have to ask ourselves whether the informal arrangement you two made between you is entirely fair to the remaining members of the family.”

His tone was casual, but I could see the gleam in his eyes, and I shouted out, suddenly furious.

“What ”informal arrangement‘? I told you, I paid good money – I signed papers…“

Laure put her hand on my arm.

“Yannick didn’t mean to upset you, Mamie.”

“No one’s upset me,” I said stonily.

Yannick ignored that and continued:

“It’s just that some people might think that an agreement such as you made with poor Papa – a sick man desperate for cash – ”

I could see Laure was watching Pistache, and cursed under my breath.

“Besides the unclaimed third that should have belonged to Tante Reine – ”

The fortune under the cellar floor. Ten cases of Bordeaux laid down the year she was born, tiled over and cemented into place against the Germans and what came later, worth a thousand francs or more per bottle today, I daresay, all awaiting collection. Damn. Cassis could never keep his mouth shut when it was needed. I interrupted harshly.

“That’s being kept for her. I haven’t touched any of it.”

“Of course not, Mamie. All the same…” Yannick grinned unhappily, looking so like my brother that it almost hurt. I glanced briefly again at Pistache, sitting bolt upright in her chair, face expressionless. “All the same, you have to admit that Tante Reine is hardly in any position to claim it now, and don’t you think it would be fairer to all concerned – ”

“All that belongs to Reine,” I said flatly. “I won’t touch it. And I wouldn’t give it to you if I could. Does that answer your question?”

Laure turned to me then. In her black dress, with the yellow lamplight on her face, I thought she looked quite ill.

“I’m sorry,” she said, with a meaningful glance at Yannick. “This was never meant to be about money. Obviously we wouldn’t expect you to give up your home-or any part of Tante Reine’s inheritance. If either of us gave the impression…”

I shook my head, bewildered.

“Then what on earth was all that-”

Laure interrupted, her eyes gleaming.

“There was a book…”

“A book?” I repeated.

Yannick nodded.

“Papa told us all about it,” he said. “You showed it to him.”

“A recipe book,” said Laure with strange calmness. “You must have all the recipes by heart already. If we could only see it… borrow it…”

“Of course, we’d pay for anything we used,” added Yannick hastily. “Think of it as a way to keep the Dartigen name alive.”

It must have been that-that name-which did it. Confusion, fear and disbelief warred in me for a while, but at the mention of that name a great spike of terror pierced me and I swept the coffee cups off the table, where they shattered against my mother’s terra-cotta tiles. I could see Pistache looking at me strangely, but could do nothing but follow the seam of my rage.

“No! Never!”

My voice rose like a red kite in the little room, and for a second I left my body and looked down upon myself emotionlessly, a drab sharp-faced woman in a gray dress, her hair drawn fiercely back into a knot at the back of her head. I saw strange comprehension in my daughter’s eyes and veiled hostility in the faces of my nephew and niece, then the rage slammed into place again and I lost myself for a while:

“I know what you want!” I snarled. “If you can’t have Mamie Framboise, then you’ll settle for Mamie Mirabelle. Is that it?” My breath tore through me like barbed wire. “Well, I don’t know what Cassis told you, but he had no business, and nor have you. That old story’s dead. She’s dead, and you’ll get none of it from me, not if you were to wait fifty years for it!”

I was out of breath now, and my throat hurt from shouting. I picked up their most recent present-a box of linen handkerchiefs lying on the kitchen table in their silver wrapping-and pushed it fiercely at Laure.

“So you can take your bribes,” I yelled hoarsely, “and you can stick them up your fancy ass with your Paris menus and your tangy apricot coulis and your poor old Papas-”

For a second our eyes met and I saw hers unveiled at last and filled with spite.

“I could talk to my lawyer-” she began.

I began to laugh.

“That’s right!” I hooted. “Your lawyer! It always comes to that in the end, doesn’t it?” I yarked savage laughter. “Your lawyer!”

Yannick tried to calm her down, his eyes bright with alarm.

“Now, chérie… you know how we – ”

Laure turned on him savagely.

“Get your fucking hands off me!”

I howled laughter, cramping my stomach. Points of darkness danced before my eyes. Laure’s eyes shot me with hate – shrapnel, then she recovered.

“I’m sorry.” Her voice was chilly. “You don’t know how important this is to me. My career…”

Yannick was trying to steer her toward the door, keeping a wary eye on me.

“No one meant to upset you, Mamie,” he said hastily. “We’ll come back when you’re more reasonable – it’s not as if we were asking to keep the book…”

Words like spilled cards sliding. I laughed harder. The terror in me grew, but I could not control my laughter, and even when they had gone – the screech of their Mercedes’ tires oddly furtive in the night – I still felt the occasional spasm, souring into half – sobs as the adrenaline fell from me, leaving me feeling shaken and old.

So old.

Pistache was looking at me, her face unreadable. Prune’s face appeared round the bedroom door.

“Mémée? What’s wrong?”

“Go to bed, sweetheart.” said Pistache quickly. “It’s all right. It’s nothing.”

Prune looked doubtful.

“Why was Mémée shouting?”

“Nothing.” Her voice was sharp now, anxious. “Go to bed!”

Prune turned reluctantly. Pistache closed the door.

We sat in silence.

I knew she’d talk when she was ready, and I knew better than to rush her. She looks sweet enough, but there’s a stubborn streak in her all the same. I know it well; I have it too. Instead I washed the dishes and the cups, dried them and put them away. After that I took out a book and pretended to read.

After a while Pistache spoke.

“What did they mean about a legacy?”

I shrugged. “Nothing. Cassis made out he was a rich man so that they’d look after him in his old age. They should have known better. That’s all.”

I hoped she might leave it at that, but there was a stubborn line between her eyes that promised trouble.

“I never even knew I had an uncle,” she said tonelessly.

“We weren’t close.”

Silence. I could see her going over it in her mind and I wished I could stop the circle of her thoughts, but knew I couldn’t.

“Yannick’s very like him,” I told her, trying for lightness. “Handsome and feckless. And his wife leads him like a dancing bear.”

I demonstrated mincingly, hoping for a smile, but if anything her thoughtful look deepened.

“They seemed to think you’d cheated him somehow,” she said. “Bought him out, when he was ill.”

I forced myself to pause. Anger at this stage would not help anyone.

“Pistache,” I said patiently. “Don’t believe everything those two tell you. Cassis wasn’t ill, at least, not in the way you think. He drank himself into bankruptcy, left his wife and son, sold off the farm to pay his debts…”

She watched me curiously, and I had to make an effort to keep my voice from rising.

“Look, that was all a long time ago. It’s over. My brother’s dead.”

“Laure said there was a sister.”

I nodded. “Reine-Claude.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

I shrugged.

“We weren’t – ”

“Close. I gathered.”

Her voice was small and flat-sounding.

Fear pricked at me again, and I said more sharply than I had intended:

“So? You understand that, don’t you? After all, you and Noisette were never – ”

I bit the words short, but too late. I saw her flinch and cursed myself inwardly.

“No. But at least I tried. For you.”

Damn. I’d forgotten how sensitive she was. All those years I took her for the quiet one, watching my other daughter grow wilder and more willful day by day… Yes, Noisette was always my favorite. But until now I thought I’d hidden it better. If she had been Prune I would have put my arms around her, but to see her now, this calm, close-faced woman with her small, hurt smile and sleepy cat’s eyes… I thought of Noisette, and how, out of pride and stubbornness, I had made her a stranger to me. I tried to explain.

“We were separated a long time ago,” I told her. “After… the war. My mother was… ill… and we went to live with different relatives. We didn’t keep in touch.” It was almost true, at least as close as I could bear to tell her. “Reine went to… work… in Paris. She… fell ill too. She’s in a private hospital near Paris. I visited her once, but…”

How could I explain? The institution-stink of the place, boiled cabbage and laundry and sickness, televisions blaring in soft rooms full of lost people who wept when they didn’t like the stewed apples and who sometimes shouted at one another with unexpected viciousness, flailing their fists helplessly and pushing each other against the pale green walls. There had been a man in a wheelchair-a relatively young man with a face like a scarred fist and rolling, hopeless eyes-who had screamed I don’t like it here! I don’t like it here! during the whole of my visit, until his voice faded into a drone and even I found myself ignoring his distress. One woman stood in a corner with her face to the wall and wept, unheeded. And the woman on the bed-the huge bloated thing with the dyed hair, round white thighs and arms cool and soft as fresh dough, smiling serenely to herself and murmuring… Only the voice was the same, without which I would never have believed it, a little-girl’s voice chiming nonsense syllables, the eyes as blank and round as an owl’s. I made myself touch her.

“Reine. Reinette.”

Again that vapid smile, the little nod, as if in her dreams she were a queen and I her subject. She had forgotten her name, the nurse told me quietly, but she was happy enough; she had her “good days” and she loved the television, especially the cartoons, and to have her hair brushed while the radio played…

“Of course we still have our bad spells,” said the nurse, and I froze at the words, feeling something shrivel in my stomach to a bright hard knot of terror. “We wake in the night”-strange, that pronoun, as if by taking on part of the woman’s identity she might be able to somehow share in the experience of being old and mad-“and sometimes we have our little tantrums, don’t we?” She smiled brightly at me, a young blonde of twenty or so, and I hated her so much in that moment for her youth and cheery ignorance that I almost smiled back.

I felt the same smile on my face as I looked at my daughter, and hated myself for it. I tried again for a lighter note.

“You know what it’s like,” I said apologetically. “Can’t bear old people… hospitals. I sent some money…”

It was the wrong thing to say. Sometimes everything you say is the wrong thing. My mother knew that.

“Money,” said Pistache contemptuously. “Is that all people care about?”

She went to bed soon after, and nothing was right again between us that summer. Near the end of the holidays she left a little earlier than usual, pleading fatigue and the approach of the school term, but I could see something was wrong. I tried to talk about it to her once or twice, but it was no good. She remained distant, her eyes wary. I noticed she was receiving a lot of mail, but I thought nothing of it until much later. My mind was on other things.