Читать книгу A Sharp Intake of Breath - Джон Миллер - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

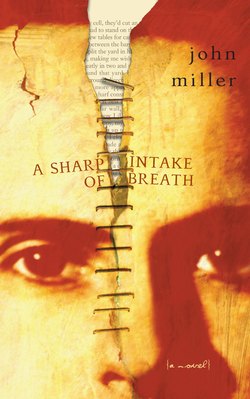

The orange sunset

ОглавлениеTo trace the moment, the very first moment when my life was set upon a different course, that was impossible. Too many factors, too many decisions, too much being determined by whim and personality and random untraceable influence. Still, if I tried to pick a little, like dragging a thumbnail across a roll of tape, I could snag a beginning of sorts, even if it wasn’t really the beginning, even if it was only the remnant of a previous tear that had settled back and now clung to the rest of a sticky, tightly wound past.

There was a day that I remembered, a day when Lil’s fascination with Emma Goldman began, that set in motion a chain of events that would affect us all. It was in November of 1926, and I was only ten. I remembered that day for two reasons, and the first had nothing to do with Emma.

The day started with all of us at the kitchen table, as it always did. We were a family who sat and ate breakfast together no matter what, because other things—jobs, the store, political meetings—might interfere and separate us for lunch or supper.

My parents were avid readers of the morning newspaper. One newspaper, the Toronto Mail and Empire, they read to keep track of their class enemies. Others, they read because of political interest or because the writers spoke to our community. The communist weekly Vochenblatt and the daily Yidisher Zshurnal—the Hebrew Journal—were in this category, though I believe they also read these two to see who was the latest person to be denounced. The Yiddish press was vicious and retributive and heaven help you if you were on the other side of their graces. Reading those papers satisfied a ghoulish fascination: who would be torn to shreds this week? Whose character would be assassinated ruthlessly? My parents read these denunciations, clucked, and shook their heads, but they kept going back for more.

Our father, Saul Wolfman, had emigrated, along with his parents, from Russia. They settled in the Ward, the neighbourhood in Toronto mainly populated by Jewish immigrants, bordered by College and Queen on the north and south, and Yonge and University on the east and west. Our mother was born in New Liskeard, of all places: a small, bilingual farming community near the Quebec border in northeastern Ontario, where her Galician peasant parents had settled. There, isolated from any other Jews, they eked out a livelihood. But farm life proved difficult, and in 1908, after too many harsh winters, they moved to Toronto, where they opened a second-hand clothing store with money borrowed from a cousin.

My parents’ families attended different synagogues—in those days they were organized along ethnic lines—but Ma and Pop met at a secular community dance one weekend. The next year, they married at the Holy Blossom Temple, which upset their families, but it upset them equally, which was the important thing. By 1910, the Holy Blossom had become notorious for its more liberal congregants, some of whom didn’t even wear head coverings when they prayed.

Maybe it was there my parents first became interested in politics. Not that they needed the Holy Blossom. If a person was working class in Toronto in the early 1900s, the rising proletarian movement in Russia was an irresistible draw to one of the city’s numerous labour organizations. My parents chose the Arbeiter Ring—the Workmen’s Circle, a local organization of mostly Jewish workers in the shmata trade. Much later, in ’27, they joined a more left-leaning faction that broke off and became known as the Labour League. By that time, the Russian Revolution had fired their imagination, and, choosing from an ever-lengthening menu on the spectrum of the political left, my parents identified themselves with the Russian Mensheviks, though they were proud to remain officially unaffiliated.

We grew up with a steady diet of Menshevik ideology and promotion of Labour League activities. I use the word diet in the sense of a regimen, or the modern American sense that connotes near starvation with nutritional value coming a distant second. Political thought in the Wolfman family was doled out in spare but regular allotments at the table, like dessert. To us children, it was an uninteresting dessert, much like stewed prunes or an apple. None of us joined the Labour League, much to our parents’ chagrin. Bessie was not interested in politics in any way, Lil became involved with an anarchist branch of the Workmen’s Circle, and me? Well, I just got in trouble and went to jail.

At breakfast that morning in November of 1926, Ma was flipping through the pages of the Mail and Empire, and she came across a small piece in the middle of the society section.

“My, my! Have you ever seen such a diamond? It’s enormous!” She flashed the page at us. I caught its headline, “Lady Fister stuns socialites with Orange Sunset,” but didn’t get a good look at the picture. Besides, I was ten years old, only cared about the Tarzan comic strip, and had no reason to concern myself with society folk.

She spotted me spooning absent-mindedly at my porridge. “Toshy, eat up and don’t slouch.” Then, her eyes back on the page: “This woman looks familiar.”

I considered my gruel. Ma always salted it too much.

“Can I see?” said Bessie, who was sitting across from me, with perfect posture. She’d already finished her entire bowl.

Ma passed her the newspaper. “That woman’s diamond brooch was a wedding gift from her husband,” she said.

“I know how to read, Ma,” said Bessie, squinting at the text.

Lil was sitting beside her and snatched the paper.

“Hey! I wasn’t finished.” Bessie pulled it back, leaving a ripped corner in Lil’s hands.

“You take too long.”

“Girls, stop it. Bessie, read us what it says.”

“It saaaaays,” she glared at Lil, who was leaning in to read over her shoulder, “‘Lady Fister makes a rare showing of the Orange Sunset, a thirty-six car-AT diamond...’ What’s a car-AT, Ma?”

“It’s pronounced ‘carrot’ and it’s a measurement for how much a diamond weighs. Thirty-six carats is very, very big.”

“‘...a thirty-six carat diamond that her husband purchased in South Africa after fighting in the Boer War. The diamond is an unusual amber colour, bezel-set in a gold brooch, and surrounded by twelve emeralds. After settling in Toronto, Lord Fister built a successful import-export business and he and Lady Fister had a son early in their marriage. Sources say the diamond is worth a small fortune.”

I’d been pretending not to listen but I picked my eyes up from my porridge. “A fortune? Read what it says about that, Bessie.”

“Hold your horses. I’m getting to that. It says, ‘Lady Fister almost never wears her wedding gift, and though some say it is because she is afraid of theft, those who know her well say that she finds it too ostentatious to wear in public.’”

“Where else would she wear it?” said Pop. “In the bathtub?”

We all laughed. I reached across the table. “Lemme see.”

Bessie passed me the paper, but in a wide arc to avoid Lil’s clawing hands.

I saw the photograph. There was a middle-aged couple, the woman sporting an enormous diamond on the breast of her gown. She was stout, much shorter than her husband, and though she wore a fur coat, a hat, and glasses, I knew her immediately.

“That’s Nurse Grace!”

“Who?” said Pop.

“Nurse Grace, who took care of me when I was in the hospital.”

“Nonsense,” said Ma. “That woman is rich. Rich men’s wives don’t work as nurses. Besides, you can’t possibly remember that; you were just little.”

“I remember her. She was nice to me.”

Ma got up from her chair and came around behind me. “My God, Saul, he might be right. She must have a very progressively minded husband.”

“She said her husband gave her permission because she loved being a nurse. And she also told me about the diamond.”

My parents’ faces showed their skepticism.

“I remember!”

And I did.

When Ma brought me to Dr. Grover, I was almost five years old. It was early 1921, a bright, cold day in January, and we walked for an hour through the unplowed Toronto streets to make our appointment. Occasionally, we’d find one narrow track in the middle of a wide boulevard and follow it, the snow on either side of me reaching to above my knees. Ma carried me as much as she could, but I had to walk most of the way, complaining that she was tugging too much on my arm. She told me we would be late, that my legs were sinking too deep and that if she didn’t pull me along, I might get stuck. She brought a bag full of money to the hospital. Dr. Grover gently pushed it back across the desk and told her she should keep it until afterwards, and then send a bank draft.

When I was a newborn, my parents had decided to wait even to have my palate fixed. The operations were expensive and Pop had heard from friends about the humiliating process they’d have to go through before the hospital determined it would pay. Pop was a proud man and decided they’d save for the operations themselves. They spent five years at it, putting aside a portion of the meagre proceeds of their silk and cotton retail store on St. Patrick Street. Without telling Pop, Ma went with her hand out to the Toronto Hebrew Benevolent Society, and since she kept the books, she was able to conceal the donation as business profits.

My mother, if I may say so, was a dogged and intelligent woman. She was impressed with modern medicine but she was also skeptical and inquisitive. She sought to educate herself rather than rely solely on what the doctors told her. She read voraciously whatever she came across—critically, laughing at advice she found preposterous and mocking it to anyone who would listen. One day, years later, I found a booklet in her house called “Your Baby Has a Cleft Palate?” Ma had underlined the following passages: “His condition may have been a shock to you. Stop blaming yourself ... and stop regarding your husband with questioning eyes. No one knows as yet why this developmental failure occurs and until science discovers the reason, you should stop worrying about it.”

She had scribbled “What nonsense!!!” in the margin. I wondered which part she felt was three-exclamation-mark nonsense: that parents actually blamed themselves for the condition, that somehow a husband’s indiscretion might be responsible for a birth defect, or that saying she shouldn’t worry would be enough to allay her fears.

With Dr. Grover, however, Ma’s criticism drained away, as though it were light rainfall, and his smile, the porous earth into which it seeped. Even though Dr. Grover had embarrassed her by refusing her bag of money, she spoke of him with reverence. A young, single man helping sick babies, she said. He knew all of the latest methods. Maybe it was better, she rationalized, that they had to wait five years. When I was born, Dr. Grover was away treating wounded soldiers in France, just shipped off to help in the field hospitals of Verdun. The doctor who would have operated in his absence might have been older and perhaps not well versed in modern medical techniques, Ma speculated. Dr. Grover, on the other hand, had studied at Yale University. He was handsome and kind. If only he’d been Jewish, she would’ve surely introduced him to a single friend.

I mostly remember a big man with round glasses, a wide forehead, and a wild tousle of auburn hair who had halitosis and who made me tilt my head back too far while he breathed into my open mouth. I remember his nurse much better, and more fondly: a stout Englishwoman who said to me, “Here at the hospital they call me Nurse Fister, but you can call me Nurse Grace.”

She had limpid blue eyes, sat with me when my parents couldn’t be there, and said “there, there,” a lot. She made me feel safe by stroking my cheek.

Before giving me a needle she said, “Grip your mother’s index finger, as tight as you can.” I squeezed hard, until my hand hurt so much I didn’t notice the needle at all.

One afternoon, about a month after we first met Dr. Grover and Nurse Grace, the doctor stitched together the roof of my mouth, applying an aluminium splint to keep it together and to prevent me from sucking at the horsehair stitches. Nowadays, children born like me have better treatment, and it’s free. Back then there were specialists just as there are today, and the surgeons did the best they could, but the methods were less refined. The instruments appeared medieval, with hooks and barbs in places that couldn’t possibly have been for anything but show. To fix a lip, for instance, they’d jab needles from one side of the cleft to the other and draw the sides together with sutures wrapped around the needles in figure eights, like tying a boat to butterfly moorings. Crude methods that did the trick but aesthetically weren’t very satisfying. Even fifteen years later, when I had that operation, the techniques hadn’t significantly improved.

Nurse Grace fussed over me during my recovery. When Ma and Pop weren’t there, she told me stories of England, of her husband’s exploits in South Africa, and of a beautiful amber diamond called the Orange Sunset, which he brought back for her as a wedding present.

Nurse Grace stroked my hair when I complained about the pain. Her voice was a soothing balm. I listened to her lilting tones while I stared at ceiling tiles or at a tiny spider spinning her web in the corner of the room, or considered the gurgling radiator in the background, a counterpoint to the gurgling in my throat.

Eight days later, they removed the splint, and I was home. I remember a marked increase in toys, and being doted on by Ma and my sisters and various relatives and neighbours. Even by Pop.

MY PARENTS HAD NEVER SAID IT ALOUD, but they believed I was slow. It didn’t help that the doctors told them I might be, that Mrs. Debardeleben had confirmed it. It didn’t help that I barely spoke, so afraid was I of what would come out. It was in this context that at breakfast that morning, my memory of Nurse Grace had made an impression.

It made a bigger one, a few months later, when the neighbours had a small fire in their shop. It was quickly extinguished, but all of our merchandise had to be removed from the shelves and triaged: aired out, washed, or thrown away. When it was time to put the salvaged stock back, I told Pop he’d gotten the order of the silk bolts wrong when he’d rehung them.

“They go blue-red-pink-beige-white, not red-blue-pink-white-beige,” I said.

“You can’t possibly remember that.” “You should listen to him,” said Bessie. “He remembers things he sees.”

Years later, I’d be told that scientists didn’t believe in photographic memory. All I knew was that I had an ability others didn’t have to remember things I saw—the location and sequence of objects and the placement of words on a page. When I spoke, my words sometimes came out unformed and escaped here and there, but every word I read, every image I saw got ensnared, as if in a sticky web, waiting to be retrieved.

Pop stood back and took direction from me as I reassembled the merchandise, placing rainbows of fabric in exactly the right order on the display tables. When I saw how pleased he was, I became excited and told him I knew our whole inventory off by heart. Then, my parents were impressed. They were relying on me for something.

My excitement was short-lived.

Rather than deciding I was smart, they pigeon-holed me. I was still a freakish, deformed idiot, but now I was an idiot savant who could briefly be relieved from his plodding stupidity to do parlour tricks or menial tasks. Bessie knew that I remembered things I saw, but she hadn’t told my parents before then because to do so would have been to relay information that would have blown her cover as the perfect daughter. Even though Lil probably would’ve gotten in much more trouble, and she could’ve had the pleasure of taking Lil down with her, Bessie resisted the temptation. I didn’t fully understand, until then, how much my parents’ approval meant to her.

Until they discovered my special gift, Ma had delegated the keeping of the inventory solely to Bessie, who had shown some promise in arithmetic at school. It was the only subject she excelled in, and our parents wanted to encourage her. I used to follow Bessie around when she did her duties, looking at the lists she made and noting the monthly changes, how she reconciled them with the sales records. It was hard to account for a few yards of cloth—the fabric our parents sold was kept on large bolts and sold by the foot or the yard, so to be precise in the inventory would have meant unravelling and measuring, and who had the time or space for that? Another method was weighing the bolts, but we didn’t have a scale. Consequently, we counted the layers at the top of a bolt and estimated roughly that two layers was one yard. In addition, Ma asked Bessie to make a list of the number of ends—the bolts with fewer than four yards on them—and to note which colour and type of material they were.

One day, I saw Bessie checking and re-checking the list, wearing her eraser to the nub, and going back into the storefront three times to start over.

“What’s wrong?” I kept asking, following behind as she ignored me and became more frantic.

“Ma’s gonna kill me,” she eventually muttered, walking and counting with her fingers. “I think I messed up the ends count—again. There are fifteen fewer this month, but I can only account for fourteen when I look at the sales record. I think I might’ve counted wrong again. This is the third month it’s happened. I thought there were twenty-four last month, but maybe there were only twenty-three. Promise you won’t tell Ma; she’ll have my head.”

“I promise,” I said. Then, after a minute or two, “You didn’t count wrong, you know. There were twenty-four last month. You wanna know which colours?”

“Don’t bother me right now, Toshy. This is important.”

“I’m telling you, I know the colours.”

She stared at me and folded her arms. “You remember the colours. Sure. I’d have to look at my notebook to know that.”

“I just remember. I’ll show you.” I proceeded to walk the perimeter of the store, pointing out the precise locations where those fifteen bolts had been and also naming their colours, including the missing one, and ignoring this month’s new ends. Bessie followed me and checked off the ones I called out against her list. “And the missing one was a kind of blue.”

“How did you do that?” She scrutinized me like you would a magician if you were trying to see where up his sleeve he’d hidden the rabbit.

“I just remember things when I see them.”

“What kind of things?”

“All kinds of things...” I searched for an example. “Oh! Like the Tarzan comic!”

“Well, that’s not too hard. It has four panels at most, and you just read it an hour ago.”

“No. I mean I remember the words from every one of them. Every day.” I was crazy about Tarzan. I loved how strong he could be without ever speaking a word. I loved that people didn’t mock him for being like the animals. They thought he was mysterious. I would’ve cut out the comic strip if Ma hadn’t wanted the paper intact, in case she needed to wrap things. It didn’t matter; I could retrieve the images any time I wanted.

“Prove it.”

“Okay.” I closed my eyes and chose a day from December, the last day of school before the holidays. An image flashed in my mind, and I started reciting the words in the dialogue bubbles. I made the sound effects too, waved my arms like the gorillas, and jumped up on the tables in the store to act it all out. Bessie laughed. I retrieved the next image, and so on. I played all the parts, Tarzan, Jane, the animals, and stray hunters and villains that entered the storyline, until Bessie said, “Okay, stop it! I believe you. Holy smokes, that’s really weird.”

“It is?” Great, I thought, just great. Another weird thing about me. That was exactly what I needed.

“In any case, this doesn’t help me figure out what happened to those extra bolts.”

“Did you count the ones Lil takes into the backyard?”

“Excuse me?”

“Sometimes I see her taking an end and giving it to a man she meets in the backyard.”

Bessie’s eyebrows lifted. “No. No, I did not count those ones. Thanks, Toshy.” She patted me on the head. I was proud that I’d solved the mystery. “I think I’m going to have to have a little chat with our sister when she comes home.” There was a sharpness to Bessie’s voice. Later, I overheard my sisters arguing in their bedroom. With an ear pressed to the door, I couldn’t make out everything, but I did catch the crucial bits.

Bessie said, “I don’t care who needs clothes, Lil. You can’t save the whole world, especially not by stealing from Ma and Pop!” Then Lil said, “They wouldn’t even notice,” and Bessie said, “I noticed.” Then Lil: “I promise I won’t do it again, but if you tell Ma and Pop, I’ll tell them you’ve already been to second base.” There was a silence, then Bessie hissed, “I trusted you!” After that, all I heard was angry mumbling.

Bessie didn’t tell. At first, I thought she sympathized with Lil’s generosity, but then I thought no, she just didn’t want to explain to Ma why she’d gone three months without telling her she’d screwed up the count. It had to be that, because why would our parents care if she played baseball?

The next month, everything checked out perfectly.

As I BEGAN TO EXPLAIN, telling my family that I remembered Nurse Grace’s stories about the Orange Sunset had one consequence worth noting: it convinced my parents it might not be a complete waste of time to bring me on the planned outing that evening. Emma Goldman was in Toronto on tour, and everyone was going to hear her. Emma Goldman, the most dangerous woman in the world! By then, people already called her that, and I was curious to see what could be so scary. I didn’t know or even care that she never preached violence, that people who called her dangerous didn’t know a damn thing about her.

Normally, Emma lectured on controversial progressive subjects such as free love, by which she didn’t mean promiscuity—though she wasn’t opposed to that—but rather the freedom to love whomever you wished. In those days, when marriages were arranged contracts trapping either loveless couples or people for whom love had blossomed but then wilted, it was a radical notion to choose and change partners at will, just to follow the heart. In the early 1900s, she was also speaking out in favour of birth control, sexual and personal emancipation for women, and even, Ari has recently told me, homosexual rights.

In Toronto’s Jewish community, to go to hear her speak you didn’t need to be an anarchist sympathizer. She was a Jew and an infamous international celebrity. Besides, that night, her lecture topic was to be the playwright Henrik Ibsen and the modern drama, and what harm could there be in that? My parents packed us into the streetcar on that cold night in 1926 and took us to Hygeia Hall. We took seats near the back of the auditorium, near the police who were lined up and scribbling things in their notebooks.

Although I heard the lecture first-hand, it was a story Lil would tell and retell, always as if the talk had been the night before. It was hard, even for someone like me, to sift out what was authentically my memory from what was hers. Once, years later when Ari was only nine, we were over at Bessie and Abe’s, eating hors d’oeuvres in their living room, and Lil was telling the story. She took the opportunity, as she often did, to tease our older sister.

“Your grandma Bessie sat through the whole lecture with her arms crossed,” she said. “Everyone around her, including our father, was on the edge of his seat, but your grandma just sat there with a sour puss. Even your uncle Toshy appeared to be interested and he was only your age, Ari.”

Bessie dismissed Lil with a wave of the hand. “It was winter. It was cold in that hall, and the woman was preaching nonsense, as she always did.”

Lil shrugged. “That’s your opinion,” she said, and then Bessie said, “Yes it is,” and they both shrank into their corner of the sofa. There was a chilly silence until Susan changed the subject.

It was true that Emma was a magnificent speaker. Her voice was stern and commanding that night, and her eyes, through those spectacles, appeared to bore through you as they passed in your direction. Lil said her words came at her in waves: huge, powerful breakers soaked with significance. Emma spoke that night about Nora’s enlightenment in The Doll’s House. Nora left her husband, she explained, not because she was tired of wifely duty or because she was making a stand for women’s rights. She left because she’d lived for eight years with a stranger, borne him children, even, and what could be more humiliating than realizing that the person with whom you live in close proximity hasn’t the slightest interest in you?

The hall was packed and noisy, the air smoky, the crowd boisterous, and they challenged Emma’s ideas during the question period. Men and women pointed fingers and gesticulated wildly, standing on chairs to be heard. Emma’s responses were witty, quick, and playful, and she ultimately had us all entranced, even Bessie, though she would never admit it. Even me, though I was disappointed she hadn’t talked about blowing up buildings.

This tiny force of nature with round glasses and thick jowls was telling women they could be anything they wanted, that they had a right to be thought of as individuals, and this, Lil had never before considered.

“By her very example,” Lil would say, when she told the story, “by her hand slapping the lectern to emphasize the importance of her message, she was showing us that the key to liberation was to first free one’s mind.” Her eyes were still wide with wonder, all those years later.

I can only imagine what it must’ve been like for her after that night, to watch the women in our family, our mother and sister, and see only captives, chained to a predictable future and uninspired dreams. As Lil grew up and began to excel in school, it was inevitable that a chasm would open between them. Our parents were proud of her scholastic accomplishments, but they worried about her ambition. They were concerned by her impatience with injustice. Bessie tried to be an older sister the only way she knew how, to protect her and give advice, but Lil wasn’t receptive to Bessie’s conservatism and wasn’t good at hiding her feelings. Those feelings, a mixture of pity and superiority, were the perfect recipe for condescension.

When I arrived at Kingston Pen in July of 1935, I was stripped of my belongings and clothes, given a uniform, and taken into a small room that was painted green and had a long table against the far wall, a simple wooden chair in the centre, and four hanging lamps evenly spaced. Six people sat behind the table shuffling paper, barely acknowledging me as I was seated in front of them. The guard had told me before going in that this was the Classification Board, where they would be assessing my educational and occupational record and testing me for my mental stability and my physique. Also, they would try to determine if I was a recidivist.

I didn’t know the word recidivist then but the guard explained it meant you would return to your life of crime and sinfulness. How they’d be able to tell that from meeting someone for the first time and asking him a few questions, I didn’t know. I pictured a person cracking under the pressure, finally shouting, “Yes! Yes, I’d do it again. Again! Over and over again, I tell you!” and then throwing his head back with a maniacal laugh.

I sat down on my hands, hugging my arms close to my sides. The cotton uniform they’d given me was stiff and itchy and the room smelled of damp sweat and mould. The men behind the table introduced themselves one by one. The first was the warden for both Kingston and Collins Bay penitentiaries, Lieutenant Colonel Craig. He was a thin man of about fifty who scrunched a monocle in one eye. He had a friendly smile and didn’t look at all like a lieutenant colonel. Next to him was Mr. Fowler, a Brit with a bushy grey moustache who was the deputy warden. He was stockier than his boss, and he mostly stared at his notepad, even when it was his turn to ask me questions.

Next in line was the chief keeper of Collins Bay, a few miles down the road. Collins Bay was, in those days, a new prison, still under construction, though they had started to move inmates in already. The chief keeper’s name was Frank Flaherty, and his eyes set on me like hooks trying to rip out secrets. Flaherty had a scar running from his bulbous, ruddy nose, down over his left cheekbone, ending near a sharp chin. Beside him were the prison medical officer, Dr. Platt; the industrial overseer, Mr. Jagninski; and at the end of the table, Father MacDonald, the chaplain. These last three men were remarkably alike in their features—dull and symmetrical—and their hairstyles—short hair, middle parts, slicked back over the ears. They were all in their forties, I guessed. They wore different uniforms, though—the doctor, a white lab coat; the overseer, a dark blue shirt buttoned to the neck; and the chaplain, a black shirt and stiff clerical collar. The doctor wore round glasses and fiddled with the rims.

It occurred to me that if I were ever transferred to Collins Bay, the two people with whom I might have the most contact were Overseer Jagninski and Chief Keeper Flaherty, two people with names almost as challenging as Debra Debardeleben. I hoped it would be possible to get away with calling them “sir.”

Each person had a different way of interrogating me. The doctor, for instance, had a habit, whenever he spoke, of taking off his glasses and rubbing his eyes with the thumb or forefinger, nearly scooping out his eyeballs each time. He would heave a sigh as he did it, just before he posed a question, and it gave the impression that he was weary of having to ask it at all, that you were the umpteenth person he’d examined that morning, and that you might help him by answering quickly and by not going on and on.

Sigh. “Any history of lung disease-polio-influenza-measles-scarlet fever?” he asked, jabbing his thumb into his eye socket.

“No, sir. I had a baby sister who died of the influenza.”

He then turned to the warden and said, as though I weren’t there, “I see the judge indicated there is likely mental retardation. If you’d like me to do an assessment, I’ll need to see him separately, and we may need to call in Dr. Sherman.”

“No, that’s fine,” said Warden Craig. “He understands our questions and can answer them readily enough. Can’t you, son?” He peered at me through his monocle.

“Yes, sir. If I may, sir, I just have trouble speaking. I was born with a split palate.”

Sigh. “Mental retardation often goes hand in hand with that,” said Dr. Platt. Then he wrote a whole paragraph down in his notebook. I was going to mention my lip but stopped myself for fear he would write several pages. I’m sure he noticed the deformity anyway. The notch was only slightly covered by my wispy attempt at a moustache.

Dr. Platt finally stopped scribbling and asked me to stand with my hands clasped on the top of my head and my chest puffed out, chin up, legs apart. He examined my physique. It’d been a long day; I hadn’t been allowed to shower yet and I was embarrassed by my body odour. He circled, inspected me up and down, then took my pulse and listened to my heartbeat. I was grateful for his strong cologne. A scratchy tongue depressor was shoved in my mouth, and when I said “Ahhh,” he murmured, “Yes, I see. I see.” After the examination, he declared to the others that I was healthy enough to participate in the construction project (meaning Collins Bay Penitentiary) or in any other activity Overseer Jagninski saw fit.

Jagninski asked me questions leaning back in his chair, twirling his pen with his fingers and tapping his foot against the table leg.

“Ever done any carpentry, son?”

“No, sir, but I could learn.”

“Any farming?”

“No, sir. I’m from Toronto.”

He checked his notes to confirm that I wasn’t lying. “Oh yes, I see that now. Well, we also have a smithy, we do masonry and stone-cutting, repair engines, then there’s the laundry, the leather goods workshop, the mail room, and the shoe and clothing shop.”

“I don’t have any experience with any of those.” It wasn’t a complete lie—my parents’ store sold bulk fabric, but it was retail nonetheless and I didn’t want to end up handing out clothes. “But I’d like to try carpentry if that’s possible.”

“This isn’t a summer camp, kid,” said Chief Keeper Flaherty.

“We may need him for the construction, Mr. Jagninski,” said Deputy Warden Fowler, perusing his notebook the whole time. “I’ll check over the work schedule and let you know.”

Warden Craig then went into a long speech about reforming the convict and asked, did I want to be reformed, or did I want to end up a lifelong criminal?

“No, sir,” I said, “I mean, yes, I want to be reformed.” Was this the time they expected the defiant outburst? His question was hardly enough to make someone crack.

Warden Craig considered me then, squinted a little more through his monocle, and paused a few seconds as though to assess my sincerity. “Well, you have eleven years in here to work on that then,” he said, cheerily, as though this might be something to which I would look forward.

Very slowly, Deputy Warden Fowler wrote one word in his notebook, paused to lift up his pen and cock his head, then wrote a second.

What did he write? I considered the possibilities:

Eleven years.

Stupid retard.

Dirty liar.

Watch him.

There were several more questions, including one about my faith. Father MacDonald asked if it were true that I was “of the Hebrew persuasion,” and I confirmed that I was.

“You’ll no doubt want to be observing the Sabbath with the other Hebrew inmates, then. I’ll make sure you find out about that.”

Warden Craig asked if I could read, and when I said I could, he handed me a mimeographed list of the prison rules and a separate list of punishments, said a few more words about discipline in these four walls, etcetera, etcetera, and the guard came back to escort me to my cell.

That evening, as we were lined up, waiting for the inspection before lockdown, I hummed a tune very quietly to calm a nervous stomach. I assumed I could barely be heard by the guy next to me, and besides, the guard, who had the droopy eyes of a basset hound, was standing twenty men down the line. He must’ve had a hound’s hearing to match the droopy eyes because he jerked his head in my direction. He walked slowly, ominously towards me, stopping inches from my face and staring, close enough to smell his sour breath. Instinctively, I let my vision go out of focus.

“I’m assuming they gave you a list of the prison offences, new boy?” I felt his spittle.

I’ve never concentrated that hard, before or after, on calming myself in order to make my words come out clearly. Every inmate was waiting to hear what I was going to say and I’d found that if my speech impediment was too strong the first time people heard me, they didn’t usually give a second chance.

“Yes, sir.” It sounded clear, almost.

The guard smirked. Maybe he hadn’t put his finger on what was different. Maybe he’d assume I was French-Canadian, which probably wouldn’t help much, but at least it wouldn’t be as bad as if people thought I was stupid.

“And what do they say about singing?”

I closed my eyes and retrieved the image. “They say, ‘A convict shall be guilty of an offence against Penitentiary Regulations if he sings, whistles or makes any unnecessary noise, or gives any unnecessary trouble,’ sir.”

“Yes, Offence Number Ten. No singing. And what did I just hear you doing?”

“I was humming, sir, not singing. And it’s Offence Number Eleven, sir.”

He cracked my left shin with his truncheon and I heard chuckles. I knew it wasn’t wise to contradict him, but I couldn’t help myself. It was worth it to be cheeky, to risk it just to show people I could be clever. I closed my eyes and waited for the pain to pass.

“Are you trying to be smart with me?”

“No, sir.”

“Well then, why don’t you tell me what Offence Number Four says about being smart with an officer?”

I knew it was Offence Number Three, but I didn’t say so this time. “Treats with disrespect any officer of the penitentiary, or any visitor, or any person employed in connection with the penitentiary, sir.”

He cracked my other shin. “Then don’t contradict me, new boy.”

“I’m sorry, sir.” My legs felt wobbly.

He considered my apology, then said, “You think reciting the rules verbatim is gonna impress me?”

“No, sir.”

He smiled, stepped back, and stood there, arms akimbo. His truncheon jutted out like a sword in a scabbard. “Okay, wise guy, what’s Offence Number Twenty-Three?”

“Offering to an officer a bribe of any kind whatsoever.”

“And Number Twenty-Six?”

“Neglecting to go to bed at the ringing of the retiring bell.”

He pulled a small booklet out of his back pocket, opened it, and held it away from his face. “Hmph. What about Number Thirty, then?”

“There is no Offence Number Thirty, sir.”

The guard laughed. “They couldn’t have given you those rules more than five hours ago. You been sitting in your cell all this time memorizing them?”

“No, sir, I only read them once.”

“Well, I’ll be. He sounds like a gibbering idiot but has a few tricks up his sleeve.” My throat tightened with disappointment. “I’ve heard about people like you.” He put away the booklet, then gave a final crack, which sent me to my knees. “Watch out, new boy. I don’t like smart alecs,” he spat, then moved along, back to where he’d left off his inspection.