Читать книгу Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: With Pearl and Sir Orfeo - Джон Руэл Толкиен - Страница 6

ОглавлениеSIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT

I

WHEN the siege and the assault had ceased at Troy, and the fortress fell in flame to firebrands and ashes, the traitor who the contrivance of treason there fashioned was tried for his treachery, the most true upon earth – it was Æneas the noble and his renowned kindred who then laid under them lands, and lords became of well-nigh all the wealth in the Western Isles. When royal Romulus to Rome his road had taken, in great pomp and pride he peopled it first, and named it with his own name that yet now it bears; Tirius went to Tuscany and towns founded, Langaberde in Lombardy uplifted halls, and far over the French flood Felix Brutus on many a broad bank and brae Britain

established full fair,

where strange things, strife and sadness,

at whiles in the land did fare,

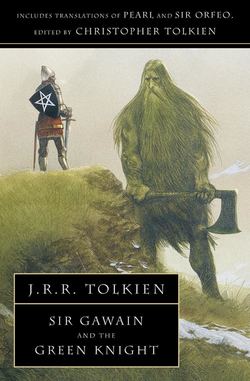

and each other grief and gladness

oft fast have followed there.

2 And when fair Britain was founded by this famous lord,

bold men were bred there who in battle rejoiced,

and many a time that betid they troubles aroused.

In this domain more marvels have by men been seen

than in any other that I know of since that olden time;

but of all that here abode in Britain as kings

ever was Arthur most honoured, as I have heard men tell.

Wherefore a marvel among men I mean to recall,

a sight strange to see some men have held it,

one of the wildest adventures of the wonders of Arthur.

If you will listen to this lay but a little while now,

I will tell it at once as in town I have heard

it told,

as it is fixed and fettered

in story brave and bold,

thus linked and truly lettered,

as was loved in this land of old.

3 This king lay at Camelot at Christmas-tide

with many a lovely lord, lieges most noble,

indeed of the Table Round all those tried brethren,

amid merriment unmatched and mirth without care.

There tourneyed many a time the trusty knights,

and jousted full joyously these gentle lords;

then to the court they came at carols to play.

For there the feast was unfailing full fifteen days,

with all meats and all mirth that men could devise,

such gladness and gaiety as was glorious to hear,

din of voices by day, and dancing by night;

all happiness at the highest in halls and in bowers

had the lords and the ladies, such as they loved most dearly.

With all the bliss of this world they abode together,

the knights most renowned after the name of Christ,

and the ladies most lovely that ever life enjoyed,

and he, king most courteous, who that court possessed.

For all that folk so fair did in their first estate abide,

Under heaven the first in fame,

their king most high in pride;

it would now be hard to name

a troop in war so tried.

4 While New Year was yet young that yestereve had arrived,

that day double dainties on the dais were served,

when the king was there come with his courtiers to the hall,

and the chanting of the choir in the chapel had ended.

With loud clamour and cries both clerks and laymen

Noel announced anew, and named it full often;

then nobles ran anon with New Year gifts,

Handsels, handsels they shouted, and handed them out,

Competed for those presents in playful debate;

ladies laughed loudly, though they lost the game,

and he that won was not woeful, as may well be believed.

All this merriment they made, till their meat was served;

then they washed, and mannerly went to their seats,

ever the highest for the worthiest, as was held to be best.

Queen Guinevere the gay was with grace in the midst

of the adorned dais set. Dearly was it arrayed:

finest sendal at her sides, a ceiling above her

of true tissue of Tolouse, and tapestries of Tharsia

that were embroidered and bound with the brightest gems

one might prove and appraise to purchase for coin any day.

That loveliest lady there

on them glanced with eyes of grey;

that he found ever one more fair

in sooth might no man say.

5 But Arthur would not eat until all were served;

his youth made him so merry with the moods of a boy,

he liked lighthearted life, so loved he the less

either long to be lying or long to be seated

so worked on him his young blood and wayward brain.

And another rule moreover was his reason besides

that in pride he had appointed: it pleased him not to eat

upon festival so fair, ere he first were apprised

of some strange story or stirring adventure,

or some moving marvel that he might believe in

of noble men, knighthood, or new adventures;

or a challenger should come a champion seeking

to join with him in jousting, in jeopardy to set

his life against life, each allowing the other

the favour of fortune, were she fairer to him.

This was the king’s custom, wherever his court was holden,

at each famous feast among his fair company

in hall

So his face doth proud appear,

and he stands up stout and tall,

all young in the New Year;

much mirth he makes with all.

6 Thus there stands up straight the stern king himself,

talking before the high table of trifles courtly.

There good Gawain was set at Guinevere’s side,

with Agravain a la Dure Main on the other side seated,

both their lord’s sister-sons, loyal-hearted knights.

Bishop Baldwin had the honour of the board’s service,

and Iwain Urien’s son ate beside him.

These dined on the dais and daintily fared,

and many a loyal lord below at the long tables.

Then forth came the first course with fanfare of trumpets,

on which many bright banners bravely were hanging;

noise of drums then anew and the noble pipes,

warbling wild and keen, wakened their music,

so that many hearts rose high hearing their playing.

Then forth was brought a feast, fare of the noblest,

multitude of fresh meats on so many dishes

that free places were few in front of the people

to set the silver things full of soups on cloth

so white.

Each lord of his liking there

without lack took with delight:

twelve plates to every pair,

good beer and wine all bright.

7 Now of their service I will say nothing more,

for you are all well aware that no want would there be.

Another noise that was new drew near on a sudden,

so that their lord might have leave at last to take food.

For hardly had the music but a moment ended,

and the first course in the court as was custom been served,

when there passed through the portals a perilous horseman,

the mightiest on middle-earth in measure of height,

from his gorge to his girdle so great and so square,

and his loins and his limbs so long and so huge,

that half a troll upon earth I trow that he was,

but the largest man alive at least I declare him;

and yet the seemliest for his size that could sit on a horse,

for though in back and in breast his body was grim,

both his paunch and his waist were properly slight,

and all his features followed his fashion so gay in mode;

for at the hue men gaped aghast

in his face and form that showed;

as a fay-man fell he passed,

and green all over glowed.

8 All of green were they made, both garments and man:

a coat tight and close that clung to his sides;

a rich robe above it all arrayed within

with fur finely trimmed, shewing fair fringes

of handsome ermine gay, as his hood was also,

that was lifted from his locks and laid on his shoulders;

and trim hose tight-drawn of tincture alike

that clung to his calves; and clear spurs below

of bright gold on silk broideries banded most richly,

though unshod were his shanks, for shoeless he rode.

And verily all this vesture was of verdure clear,

both the bars on his belt, and bright stones besides

that were richly arranged in his array so fair,

set on himself and on his saddle upon silk fabrics:

it would be too hard to rehearse one half of the trifles

that were embroidered upon them, what with birds and with flies

in a gay glory of green, and ever gold in the midst.

The pendants of his poitrel, his proud crupper,

his molains, and all the metal to say more, were enamelled,

even the stirrups that he stood in were stained of the same;

and his saddlebows in suit, and their sumptuous skirts,

which ever glimmered and glinted all with green jewels;

even the horse that upheld him in hue was the same,

I tell:

a green horse great and thick,

a stallion stiff to quell,

in broidered bridle quick:

he matched his master well.

9 Very gay was this great man guised all in green,

and the hair of his head with his horse’s accorded:

fair flapping locks enfolding his shoulders,

a big beard like a bush over his breast hanging

that with the handsome hair from his head falling

was sharp shorn to an edge just short of his elbows,

so that half his arms under it were hid, as it were

in a king’s capadoce that encloses his neck.

The mane of that mighty horse was of much the same sort,

well curled and all combed, with many curious knots

woven in with gold wire about the wondrous green,

ever a strand of the hair and a string of the gold;

the tail and the top-lock were twined all to match

and both bound with a band of a brilliant green:

with dear jewels bedight to the dock’s ending,

and twisted then on top was a tight-knitted knot

on which many burnished bells of bright gold jingled.

Such a mount on middle-earth, or man to ride him,

was never beheld in that hall with eyes ere that time; for there

his glance was as lightning bright,

so did all that saw him swear;

no man would have the might,

they thought, his blows to bear.

10 And yet he had not a helm, nor a hauberk either,

not a pisane, not a plate that was proper to arms;

not a shield, not a shaft, for shock or for blow,

but in his one hand he held a holly-bundle,

that is greatest in greenery when groves are leafless,

and an axe in the other, ugly and monstrous,

a ruthless weapon aright for one in rhyme to describe:

the head was as large and as long as an ellwand,

a branch of green steel and of beaten gold;

the bit, burnished bright and broad at the edge,

as well shaped for shearing as sharp razors;

the stem was a stout staff, by which sternly he gripped it,

all bound with iron about to the base of the handle,

and engraven in green in graceful patterns,

lapped round with a lanyard that was lashed to the head

and down the length of the haft was looped many times;

and tassels of price were tied there in plenty

to bosses of the bright green, braided most richly.

Such was he that now hastened in, the hall entering,

pressing forward to the dais – no peril he feared.

To none gave he greeting, gazing above them,

and the first word that he winged: ‘Now where is’, he said,

‘the governor of this gathering? For gladly I would

on the same set my sight, and with himself now talk

in town.’

On the courtiers he cast his eye,

and rolled it up and down;

he stopped, and stared to espy

who there had most renown.

11 Then they looked for a long while, on that lord gazing;

for every man marvelled what it could mean indeed

that horseman and horse such a hue should come by

as to grow green as the grass, and greener it seemed,

than green enamel on gold glowing far brighter.

All stared that stood there and stole up nearer,

watching him and wondering what in the world he would do.

For many marvels they had seen, but to match this nothing;

wherefore a phantom and fay-magic folk there thought it,

and so to answer little eager was any of those knights,

and astounded at his stern voice stone-still they sat there

in a swooning silence through that solemn chamber,

as if all had dropped into a dream, so died their voices

away.

Not only, I deem, for dread;

but of some ’twas their courtly way

to allow their lord and head

to the guest his word to say.

12 Then Arthur before the high dais beheld this wonder,

and freely with fair words, for fearless was he ever,

saluted him, saying: ‘Lord, to this lodging thou’rt welcome!

The head of this household Arthur my name is.

Alight, as thou lovest me, and linger, I pray thee;

and what may thy wish be in a while we shall learn.’

‘Nay, so help me,’ quoth the horseman, ‘He that on high is throned,

to pass any time in this place was no part of my errand.

But since thy praises, prince, so proud are uplifted,

and thy castle and courtiers are accounted the best,

the stoutest in steel-gear that on steeds may ride,

most eager and honourable of the earth’s people,

valiant to vie with in other virtuous sports,

and here is knighthood renowned, as is noised in my ears:

’tis that has fetched me hither, by my faith, at this time.

You may believe by this branch that I am bearing here

that I pass as one in peace, no peril seeking.

For had I set forth to fight in fashion of war,

I have a hauberk at home, and a helm also,

a shield, and a sharp spear shining brightly,

and other weapons to wield too, as well I believe;

but since I crave for no combat, my clothes are softer.

Yet if thou be so bold, as abroad is published,

thou wilt grant of thy goodness the game that I ask for

by right.’

Then Arthur answered there,

and said: ‘Sir, noble knight,

if battle thou seek thus bare,

thou’lt fail not here to fight.’

13 ‘Nay, I wish for no warfare, on my word I tell thee!

Here about on these benches are but beardless children.

Were I hasped in armour on a high charger,

there is no man here to match me – their might is so feeble.

And so I crave in this court only a Christmas pastime,

since it is Yule and New Year, and you are young here and merry.

If any so hardy in this house here holds that he is,

if so bold be his blood or his brain be so wild,

that he stoutly dare strike one stroke for another,

then I will give him as my gift this guisarm costly,

this axe – ’tis heavy enough – to handle as he pleases;

and I will abide the first brunt, here bare as I sit.

If any fellow be so fierce as my faith to test,

hither let him haste to me and lay hold of this weapon –

I hand it over for ever, he can have it as his own –

and I will stand a stroke from him, stock-still on this floor,

provided thou’lt lay down this law: that I may deliver

him another.

Claim I!

And yet a respite I’ll allow,

till a year and a day go by.

Come quick, and let’s see now

if any here dare reply!’

14 If he astounded them at first, yet stiller were then

all the household in the hall, both high men and low.

The man on his mount moved in his saddle,

and rudely his red eyes he rolled then about,

bent his bristling brows all brilliantly green,

and swept round his beard to see who would rise.

When none in converse would accost him, he coughed then loudly,

stretched himself haughtily and straightway exclaimed:

‘What! Is this Arthur’s house,’ said he thereupon,

‘the rumour of which runs through realms unnumbered?

Where now is your haughtiness, and your high conquests,

your fierceness and fell mood, and your fine boasting?

Now are the revels and the royalty of the Round Table

overwhelmed by a word by one man spoken,

for all blench now abashed ere a blow is offered!’

With that he laughed so loud that their lord was angered,

the blood shot for shame into his shining cheeks

and face;

as wroth as wind he grew,

so all did in that place.

Then near to the stout man drew

the king of fearless race,

15 And said: ‘Marry! Good man, ’tis madness thou askest,

and since folly thou hast sought, thou deservest to find it.

I know no lord that is alarmed by thy loud words here.

Give me now thy guisarm, in God’s name, sir,

and I will bring thee the blessing thou hast begged to receive.’

Quick then he came to him and caught it from his hand.

Then the lordly man loftily alighted on foot.

Now Arthur holds his axe, and the haft grasping

sternly he stirs it about, his stroke considering.

The stout man before him there stood his full height,

higher than any in that house by a head and yet more.

With stern face as he stood he stroked at his beard,

and with expression impassive he pulled down his coat,

no more disturbed or distressed at the strength of his blows

than if someone as he sat had served him a drink

of wine.

From beside the queen Gawain

to the king did then incline:

‘I implore with prayer plain

that this match should now be mine.’

16 ‘Would you, my worthy lord,’ said Wawain to the king,

‘bid me abandon this bench and stand by you there,

so that I without discourtesy might be excused from the table,

and my liege lady were not loth to permit me,

I would come to your counsel before your courtiers fair.

For I find it unfitting, as in fact it is held,

when a challenge in your chamber makes choice so exalted,

though you yourself be desirous to accept it in person,

while many bold men about you on bench are seated:

on earth there are, I hold, none more honest of purpose,

no figures fairer on field where fighting is waged.

I am the weakest, I am aware, and in wit feeblest,

and the least loss, if I live not, if one would learn the truth.

Only because you are my uncle is honour given me:

save your blood in my body I boast of no virtue;

and since this affair is so foolish that it nowise befits you,

and I have requested it first, accord it then to me!

If my claim is uncalled-for without cavil shall judge

this court.’

To consult the knights draw near,

and this plan they all support;

the king with crown to clear,

and give Gawain the sport.

17 The king then commanded that he quickly should rise,

and he readily uprose and directly approached,

kneeling humbly before his highness, and laying hand on the weapon;

and he lovingly relinquished it, and lifting his hand

gave him God’s blessing, and graciously enjoined him

that his hand and his heart should be hardy alike.

‘Take care, cousin,’ quoth the king, ‘one cut to address,

and if thou learnest him his lesson, I believe very well

that thou wilt bear any blow that he gives back later.’

Gawain goes to the great man with guisarm in hand,

and he boldly abides there – he blenched not at all.

Then next said to Gawain the knight all in green:

‘Let’s tell again our agreement, ere we go any further.

I’d know first, sir knight, thy name; I entreat thee

to tell it me truly, that I may trust in thy word.’

‘In good faith,’ quoth the good knight, ‘I Gawain am called

who bring thee this buffet, let be what may follow;

and at this time a twelvemonth in thy turn have another

with whatever weapon thou wilt, and in the world with

none else but me.’

The other man answered again:

‘I am passing pleased,’ said he,

‘upon my life, Sir Gawain,

that this stroke should be struck by thee.’

18 ‘Begad,’ said the green knight, ‘Sir Gawain, I am pleased

to find from thy fist the favour I asked for!

And thou hast promptly repeated and plainly hast stated

without abatement the bargain I begged of the king here;

save that thou must assure me, sir, on thy honour

that thou’lt seek me thyself, search where thou thinkest

I may be found near or far, and fetch thee such payment

as thou deliverest me today before these lordly people.’

‘Where should I light on thee,’ quoth Gawain, ‘where look for thy place?

I have never learned where thou livest, by the Lord that made me,

and I know thee not, knight, thy name nor thy court.

But teach me the true way, and tell what men call thee,

and I will apply all my purpose the path to discover:

and that I swear thee for certain and solemnly promise.’

‘That is enough in New Year, there is need of no more!’

said the great man in green to Gawain the courtly.

‘If I tell thee the truth of it, when I have taken the knock,

and thou handily hast hit me, if in haste I announce then

my house and my home and mine own title,

then thou canst call and enquire and keep the agreement;

and if I waste not a word, thou’lt win better fortune,

for thou mayst linger in thy land and look no further –

but stay!

To thy grim tool now take heed, sir!

Let us try thy knocks today!’

‘Gladly’, said he, ‘indeed, sir!’

and his axe he stroked in play.

19 The Green Knight on the ground now gets himself ready,

leaning a little with the head he lays bare the flesh,

and his locks long and lovely he lifts over his crown,

letting the naked neck as was needed appear.

His left foot on the floor before him placing,

Gawain gripped on his axe, gathered and raised it,

from aloft let it swiftly land where ’twas naked,

so that the sharp of his blade shivered the bones,

and sank clean through the clear fat and clove it asunder,

and the blade of the bright steel then bit into the ground.

The fair head to the floor fell from the shoulders,

and folk fended it with their feet as forth it went rolling;

the blood burst from the body, bright on the greenness,

and yet neither faltered nor fell the fierce man at all,

but stoutly he strode forth, still strong on his shanks,

and roughly he reached out among the rows that stood there,

caught up his comely head and quickly upraised it,

and then hastened to his horse, laid hold of the bridle,

stepped into stirrup-iron, and strode up aloft,

his head by the hair in his hand holding;

and he settled himself then in the saddle as firmly

as if unharmed by mishap, though in the hall he might

wear no head.

His trunk he twisted round,

that gruesome body that bled,

and many fear then found,

as soon as his speech was sped.

20 For the head in his hand he held it up straight,

towards the fairest at the table he twisted the face,

and it lifted up its eyelids and looked at them broadly,

and made such words with its mouth as may be recounted.

‘See thou get ready, Gawain, to go as thou vowedst,

and as faithfully seek till thou find me, good sir,

as thou hast promised in this place in the presence of these knights.

To the Green Chapel go thou, and get thee, I charge thee,

such a dint as thou hast dealt – indeed thou hast earned

a nimble knock in return on New Year’s morning!

The Knight of the Green Chapel I am known to many,

so if to find me thou endeavour, thou’lt fail not to do so.

Therefore come! Or to be called a craven thou deservest.’

With a rude roar and rush his reins he turned then,

and hastened out through the hall-door with his head in his hand,

and fire of the flint flew from the feet of his charger.