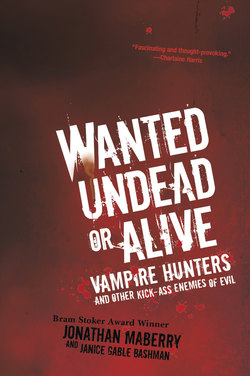

Читать книгу Wanted Undead or Alive: - Джонатан Мэйберри - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 HEROES AND VILLAINS

ОглавлениеScott Grimando, Dragon Slayer

“The Dragon Slayer was done for an Epic Poem I wrote for my book, The Art of the Mythical Woman, Lucid Dreams. The Hero sets out to prove her worth in battle donning the armor of her father who had no sons. Even the dragon underestimated her quickness and agility.”—Scott Grimando is an illustrator and conceptual artist.

HOLDING OUT FOR A HERO

We’ve always had heroes and villains. In the earliest days the hero was the caveman who throttled something and dragged it home for dinner. The villain was the brute in the next cave who throttled the hunter and stole the intended dinner.

From another view, the hero is God and the villain is the devil, and everyone who came afterward and embraced light or darkness are wannabes. To the ancient Greeks a hero was a kind of demigod, a half-breed offspring of a human and a god who was born with special powers or knowledge and who often had the support of a god. That’s not how we use the word today. By modern popular definition a hero is a person who shows courage when faced with a problem. This could be someone showing poise and determination during a fight against cancer or a soldier on a battlefield running to rescue a wounded comrade. Firemen entering a burning building are heroes. So are cops. A lot of people are heroic at different times in their lives, some more visibly than others. There is big, dramatic heroism and small, quiet heroism.

In storytelling, heroes tend to be a bit larger than life. They are the ones who stand up to threats that other people cannot face. Heroes slay dragons or hold a bridge against a horde of foes. Because of stories we tend to think of heroes as having big muscles, square jaws, and a will of iron.

But that’s a skewed view of heroism. If you’re big and tough, well trained and resourceful, then fighting the enemy is not that much of a stretch. If you’re small and weak and have no special training, standing up to danger is viewed as a much grander undertaking. This is, of course, an absurd view, because a few ounces of lead in a sniper’s bullet can plow through a muscular chest as easily as that of a ninety-pound weakling. Heroism is relative; it’s based on the individual’s emotional and psychological makeup—more so than on physical attributes.

The media tends to warp the word, using it for all the wrong reasons. They call sports stars “heroes,” confusing the word with “idols.” Hitting a home run may make fans adore you, but it isn’t heroism. Running into a burning house to rescue someone is heroism. So is standing up for a friend who is being bullied. Or saying “no” in the face of threat and intimidation.

Chris Kuchta, Evil Dead

“In Evil Dead III: Army of Darkness, the conflict between Ash and the Deadites is one of the most iconic examples of good vs. evil / hero vs. villain. It resonates with viewers in both a visceral and epic way, by showing the resolve and determination of the hero, overcoming the forces of evil by severing it at its head. The chainsaw representing the sword and the Deadite representing the classic dragon shows undertones of the classic hero’s journey, but accomplished in a contemporary world. Like Perseus and Medusa or Beowulf and Grendel it will never get outdated.”—Chris Kuchta is an illustrator and art instructor at the Kuchta Academy of Fine Art and Illustration. He has done work on films such as House of the Wolfman and for Blood Lust Magazine.

Heroes are also defined by measuring what they do against what they stand to lose. A mother who stands between her children and a rabid dog is a hero. If she fails, she might lose her life and more critically (to her) the lives of her children. If that same person was faced with the rabid dog when no helpless children are involved, the same situation might end differently. She might lose more easily; she might not find the inner reserve necessary to rise to the demands of the moment.

But we know that the extraordinary can happen. It has happened.

Heroism is also situational, and this is one of the really weird and inexplicable aspects of modern-day humans. On any given street in any big city in the world, most people not only pass one another by without acknowledgment, but they will growl, snarl, and snap if one of the other pedestrians intrudes into the bubble of their personal space to ask the time, directions, or the generosity of a quarter. And yet, let a terrorist’s bomb go off, those same people will often risk life and limb to rescue injured strangers from burning debris.

Many people go their whole lives without ever encountering the kind of circumstances that will allow them to access their inner hero. Some hear the call of the moment and fail through fear, unshakable insecurity, cowardice, or some social bias that makes them withhold rather than reach out. And yet there are those people who are called by the moment, perhaps by the voice of destiny, to step up and show their mettle. Myth, history, and fiction are filled with the everyman who becomes the hero, or the green youth who discovers in his heart an iron resolve. Circumstance can make or break.

The HBO miniseries Band of Brothers (2001) showcased this beautifully, presenting a variety of characters who, under the intense and varied pressure of combat, discover weakness or strength. That series is probably one of the most accurate, poignant, and powerful presentations of ordinary heroes.

In world myth, the hero’s journey—eloquently described by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces—is built around this process of discovery. Also known as a “monomyth,” this is a common story form in which the hero-to-be begins in the ordinary world and is drawn into an adventure, experience, or journey during which he faces a series of challenges, tasks, and trials. Sometimes he faces these alone (Indiana Jones, Spider-Man); sometimes he has companions (Luke Skywalker, Dorothy Gale). The process of facing and dealing with each challenge expands the hero’s mind, deepens his understanding of the world, and makes him stronger. Ultimately the hero must face a major challenge, a make-or-break moment that often has a lot riding on it: the hero’s life, the lives of others, perhaps a kingdom, maybe even the fate of the world. The bigger the stakes the more drama in the story.

Some people, in life and in myth, are born to be heroes, and their journey is all about discovering and then embracing their destiny. These characters often have some special gift or ability that gives them an edge so that when they face their challenges they can draw on this inner resource and win the day. That’s the case with Hercules, King Arthur, Wolverine, and Leelu from The Fifth Element (1997). These heroes are often willing to fill that role.

Unwilling heroes may also possess gifts or be chosen by destiny to rise in a time of crisis. Bilbo and Frodo Baggins were unwilling heroes. So was Harry Potter. There is usually a moment, however, when they man up and do what has to be done.

There are also antiheroes—people who seem unsuited for the role, often because of attitude issues or personality problems such as cowardice or self-absorption, but who nevertheless find that inner spark when the chips are down. Han Solo is a great example. At the end of the second act of Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) he was ready to take his reward and bug out, but a pesky conscience brought him back into the fight, and in the nick of time.

More tragic antiheroes are those who resist the call of heroism, or are even villains for a while, but who rise to the moment, often at their own expense. Annakin Skywalker’s heroism surfaced in the last few minutes of Star Wars: The Return of the Jedi (1983), and—sadly—he died. Antiheroes often have a short life span once they’ve reclaimed their better nature.

A switch on the antihero is the kind who is viewed as a hero only by one side in a conflict. Certainly Joan of Arc was viewed as a heroine by the French people, but the English burned her as a witch. Hans-Ulrich Rudel was the most highly decorated Stuka dive-bomber pilot of World War II, and the only person to be awarded the Nazi Knight’s Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds. To the Allies, however, he was a monster. During the Depression, gangsters like John Dillinger were hailed as heroes by the common man. Everything is relative.

Some people make great personal sacrifices that do tremendous good, but they do it without guns or bulging biceps, and often they fly under the radar and seldom get hung with the label of hero. Mother Teresa, Mahatma Gandhi, Rosa Parks, the Dalai Lama, and the host of unsung people working without applause to combat poverty, disease, and ethnic genocide in third world nations.

OPPOSING EVIL: CHOICE, DESTINY, OR RIGHT PLACE/WRONG TIME?

In the supernatural world heroes are often pitted against challenges no ordinary mortal is meant to face. Hunting a vampire, slaying a werewolf, driving unclean spirits from a house or from a possessed person—these are challenges that separate heroes from the vast majority of humanity (who would rather run for the hills—and sensibly so!).

What makes someone take that stand?

Sometimes it’s love. When evil invades the home and targets one or more family members, it provokes a response that’s been hardwired into us since we were lizards. “Defend the species” is a primal response. “Defend a loved one” is simply the most recent coat of paint on that ancient reflex. Defending a loved one does, however, require more active choice than simple species protection because with higher mind comes rationalization and considered self-interest. There are people who will flee in the face of attack even if it means leaving their loved ones to die. Yes, it can be argued that self-preservation is as old an impulse as species defense, but we can overcome it in order to defend others. Opting to save one’s own life instead of someone else’s is a choice. Tragic, surely; even understandable in certain circumstances…but it isn’t heroic.

A hero may oppose the threat even if he believes that it’s hopeless, or that he’ll die in the process. Heroic choices don’t always stand up to close logical scrutiny. But damn if they don’t elevate the spirit.

Given a choice, a hero will opt to do some research, prepare some weapons or charms, maybe call on a few dozen buddies to help storm the castle. That’s another benefit of higher mind: strategic thinking. And common sense…let’s not forget common sense. A hero with some horse sense is likely to end the night as a live hero rather than a dead one.

Sometimes heroism is determined by pure chance and a mix of bad luck (having to confront a monster at all) and good luck (living to talk about it). This kind of hero usually has no prep time, no encounters with cryptic mentors, and no chance to get up to speed. The moment looms and the person reacts, and through some action wins the day. The reason this person gets to be the “hero” is largely based on survival: he either has defeated the monster or saved someone else from the big bad. A person who merely “escapes” is not a hero—just a lucky s.o.b. who should now go out and buy a fistful of lottery tickets.

FIGHTING EVIL

A hero is often defined by his enemies. A person who fights a vampire the size and approximate strength of, say, Tickle Me Elmo is not likely to be rated among the greatest champions of all time. When St. George fought a fire-breathing dragon, that one made the record books. For stories to have real pop—be they mythic, biblical, or fictional—there has to be a Big Bad, and the bigger and badder the evil the more profound the struggle. It’s what makes a character into a hero. Beowulf fought Grendel and got serious points, but when he fought Grendel’s much more powerful mother, he became a much greater hero. That he later died while fighting a dragon (which also died) gives his life story a real “wow!” factor.

In more modern heroic stories there is often a bigger power gap between hero and villain. Luke Skywalker versus Darth Vader, Clarice Starling facing down Hannibal Lecter, and Indiana Jones against the entire Nazi army are examples. Wits, resourcefulness, pluck, luck, and maybe some useful personal knowledge are common among the modern hero. Even when the hero is immensely tough—Spider-Man, for example—the villains tend to be an order of magnitude tougher, like the Rhino or the Hulk.

People who believe they are empowered by God (or whoever is driving their particular belief system) can make formidable heroes. They can also be villains, depending on the point of view. During the Inquisition the Church was ostensibly the “hero” in a protracted battle against supernatural evil; however, in retrospect we can see that the Inquisition’s actions were a campaign of corruption resulting in a slaughter of innocent people.

The burden on the hero who faces the supernatural is first to determine if the enemy is actually unnatural. Not an easy thing. A large part of the hero’s challenge, then, is studying the creature, devising a series of tests to establish its nature, determining which weapons will work against it, and then actually killing the thing. For this reason the smallest portion of virtually any monster story involves actually killing the monster.

Most of it is the hunt.

VILLAINS—NATURAL AND UNNATURAL

Villains are the bad guy. Whether human, monstrous, alien, spiritual, or other, the villain is the person or being whose aim is to do some kind of harm. Real-world villains range from vicious dictators like President Robert Mugabe who has been accused of a laundry list of human rights violations to a snatch-and-grab thief who robs a convenience store.

Some villains are reluctant, and many are villains only from the perspective of political or ethical ideology. This is the case in every war ever fought.

Some villains fill that role briefly—perhaps a momentary lapse in which they succumb to greed or lust or one of those other pesky Seven Sins. Some are opportunists who see something and grab at it. The 2008 financial collapse was filled with bad guys of that kind.

Some villains, on the other hand, revel in it. Villainy is their choice. They groove on the negative energy released from their actions. This, sadly, is a pretty large category that includes child molesters, rapists, mass murderers, corrupters of youth, and many others.

Movies—perhaps more so than novels—are often structured to present the villain as the most interesting character. Filmmaker John Carpenter (Halloween, The Thing, The Fog) agrees and shared his views with us: “The villains always have the best parts. Darth Vader had the best part in Star Wars, the Wicked Witch had the best part in The Wizard of Oz, everybody loves villains. And these guys are just actors in makeup, but we all love them. They have a power to them. They’re strong. Everybody knows about them. So they become incredibly familiar. It’s hard to get people riled up and scared by them anymore because they’re so familiar to us. For Halloween we dress up as scary characters, but we love them, we enjoy them and celebrate them. That’s what movie storytelling’s all about.”

So…why the great love affair with the bad guys? “The reason we bond so much with the movie villain,” says Carpenter, “is that we secretly want that kind of freedom, to be able to break all the rules. Especially when we’re young. That’s what we long to do, we want to break the rules. That’s the appeal of horror films in general. Especially when they’re on the edge. We go in there and we want a thrill. We want to get out of normal society. But as you get older, and become more responsible it becomes less fun.”

Creating Fictional Villains

“I think the key to any villain in fiction is to make him human. He may do evil things, but he’s still a human being and he reacts to the world in a very human way, although with a complete lack of impulse control. My character of Vincent, in Whisper in the Dark, for example, feels that he has been wronged. That after he has worked so hard to make a name for himself, creating his “art,” some impostor has come along and stolen his thunder by, more or less, taking credit for his work. At least that’s the way Vincent sees it. He sees the impostor as a plagiarist—and a bad one at that. So he’s very human in his reaction, although he goes about getting revenge for this insult in ways that most of us wouldn’t think of. Or maybe we’d think of, but wouldn’t act on.”—Robert Gregory Browne is an AMPAS Nicholl Award–winning screenwriter and the author of Down Among the Dead Men (St. Martin’s, 2010).

It’s interesting to note, however, that very few people ever regard themselves as evil. Wiretaps of conversations between members of organized crime families bear this out. You rarely get statements like, “Hey, let’s go out and do some evil stuff.” Though that would really make court cases a lot easier.

However, in myth and storytelling there are plenty of villains who delight in simply being evil. That’s a club that has Satan as its chairman emeritus and includes Baba Yaga, quite a few dragons, the occasional ogre and troll, vampires, child-eating forest hags, and others. When it comes to child-eating hags there’s no moral gray area, and heroic slayage is both acceptable and encouraged.

However, these days it’s all about the gray area. Even a monster like Hannibal Lecter—a mass-murdering cannibal who was voted the second greatest villain of all time (after Darth Vader1)—was a character people actually liked. In Thomas Harris’s chilling novel, Silence of the Lambs and Jonathan Demme’s nail-biter of a film, Lecter was charming, likable, even admirable in certain ways. We rooted for him to escape from his captivity, and the warden was made to look like the villain. The character’s charisma blinded us to the bare facts that the warden was justified in maintaining the harshest security standards because the prisoner was an incredibly dangerous monster. But gray areas are at the heart of modern storytelling.

True Evil

“All of my films have tackled ‘good vs. evil’ to some extent. The most obvious is probably Pink Eye. There is a masked killer who is a victim to government testing—so the killer is not the true evil, the government is. They drug this man to the point of insanity; he escapes an asylum and kidnaps my character. I am just a nice girl trying to keep my family together and I end up tied to a bed…I won’t give away the whole story because there are some twists in there. All real good vs. evil stories are morally convoluted because nothing is ever truly black or white.”—Melissa Bacelar is an actress, model, producer, and animal activist.

New York Times bestselling author Rachel Caine shared her view on crafting these “gray area” characters: “I can’t really warm up to characters who are just one thing or another. Black or white. Real people don’t fall into those categories, and for me, the characters I create have to be realistic, if not real. My characters make mistakes. Bad choices. Sometimes, they compromise their ideals for short-term gains. I have a hard time making stock heroes or stock villains without mussing them up a little bit—most of my villains have redeeming qualities, and most of my heroes have less admirable ones. It just makes them more interesting to me.”

A lot of modern horror and fantasy fiction explores those gray areas of evil and villainy, and that makes for some fascinating reading. It also allows the writers to throw some curves at the reader. Few things are more boring than a completely predictable villain. When it’s hard to make a clear distinction as to whether someone (or something) is a villain, it infuses the encounter with paranoia, tension, and real scares.

Monsters as Social Commentary

“Zombies in storytelling are all about social commentary, not about evil. They are the perfect vehicle for allegory. To the writer, zombies can represent anything they want them to, but nothing works better than tapping into what a society is afraid of at any given point in history. A zombie trying to destroy a family barricaded away in a farmhouse could represent the decline of marriage or the destruction of the housing market. A band of the undead overrunning a city, with the way our country is now, may represent the terrorists that have been working to destroy our freedom. The zombie oozes no sexuality, like the vampire. There are no undertones there. It is not meant to seduce you, but just flat-out ruin everything you value. For a writer delving into zombies, they leave a lot of room for commenting on society and tuning into the frequency of what scares us as a collective group.”—James Melzer is the author of Escape: A Zombie Chronicles Novel (Simon & Schuster, 2010).

MINDLESS EVIL

Monster stories of all kinds, from mythological tales of hydras and sea serpents to folktales about werewolves to modern tales of zombies, often present all threats as evil. That’s not always accurate and it isn’t fair. Evil is measured by intent not by the degree of harm done. It can’t be judged according to body count because a fighter pilot in war who sinks a ship may be responsible for the deaths of hundreds of enemy soldiers, but that’s the nature of war. Dracula only killed a handful of people in Bram Stoker’s novel and yet we can all agree that he’s evil.

The challenge in determining whether something is evil or merely dangerous crops up a lot when talking about monsters. The Creature from the Black Lagoon (Universal, 1954) is an animal and a natural predator. Are we right in calling such a creature “evil” because it kills humans? It isn’t breaking any set of laws that apply to its species. No more so than a scorpion or a snake. The mistake is to equate “dangerous” with “evil.”

Zombies are another good example. In George A. Romero’s classic 1968 film, The Night of the Living Dead, the zombies kill over and over again without remorse. By the second film in the series, Dawn of the Dead, zombies had killed nearly every man, woman, and child on the planet. They are certainly threatening, relentless, and unnatural. So…does that make them evil?

Almost certainly not. Zombies, according to the Romero model, are unthinking. They are dead bodies that have been reanimated. They walk; they can use very simple tools (we see them picking up bricks or pieces of wood); they can problem-solve in a limited way (the zombie who attacks Barbara in the graveyard picks up a brick to try to smash the window after he has been unable to open the door using the handle). They can even pursue. And yet Romero—and other writers in the genre like novelists Max Brooks (World War Z), Joe McKinney (Dead City, 2006), and Robert Kirkman’s ongoing comic book The Walking Dead—have clearly established that there is no personality, no emotions, no higher consciousness of any kind.

Billy Tackett, Dead White & Blue

“When I painted Zombie Sam I thought I’d piss some folks off. That didn’t happen. The broad range of people that have become Dead White & Blue fans continues to amaze me. My Zombie Sam image is embraced equally by both the political left and right! I’ve sold shirts to both anti-war protestors and to soldiers voluntarily heading off to Iraq. Everyone seems to be able to put their own spin on him and personally I love it!”

—Billy Tackett is an illustrator and creator of the popular Dead White & Blue series of images where he zombifies iconic American images.

“Zombie stories are like a photograph in that they capture a society in a moment of time and freeze it there,” observed the late Z. A. Recht, author of The Morningstar Strain, a duology of zombie novels. “No further progress will be made. Nothing more will be manufactured. Life will go on—mostly—but the society has broken a cog and stopped in place. What remains are the echoes of that society, and now that it’s frozen, and we, the survivors, have become something more, we can look back at it and really see what we were. It also forces the human characters to expose themselves: a greedy person might successfully hide behind a curtain in a civilized society, but in an anarchic one, they will have to be openly greedy and grab what they can when they can…Similarly, a generous character might be open-handed to the extent that they do not eat enough. The situation forces the morality of the character, for good or ill, to surface and take over. A person’s morals—their principles—are the cornerstones of their personality, and I truly think that in an extreme situation, an individual will tend to revert to these cornerstones almost unconsciously, and cling to them.”

Zombie Appeal

“Zombie stories appeal to a wide set of groups on a lot of different levels. There are the darkly beautiful feelings of hopelessness and bleakness that run rampant in the genre, but there’s also the fantasy escapism of being one of the last people alive with everything left to you but also being free from the rules of a civilization that no longer exists.”—Eric S. Brown is the author of Season of Rot (Permuted Press, 2009) and The War of the Worlds Plus Blood, Guts and Zombies (Coscom Entertainment, 2009).

“You cannot judge zombies in a moral sense,” argues Dr. Kim Paffenroth, associate professor of religious studies at Iona College and author of Gospel of the Living Dead: George Romero’s Visions of Hell on Earth (Baylor, 2006). “Before the modern era, there was talk of something they called ‘natural evil’—things we’d call natural disasters or just facts of life (earthquakes, fires, diseases, etc.). Zombies would seem to fit there. It also means that zombie tales have to go one of three ways, it seems to me: either they humanize the zombies and give them more of a sense of mind and soul, or they treat them as a natural disaster (which makes some zombie movies look more like disaster movies than monster movies), or they have to focus on the evils committed by human survivors against one another.”

Jacob Kier, the founder and editor of Permuted Press, one of the most successful publishers of zombie and apocalyptic fiction, agrees. “The classic Romero-style zombies are neither good nor evil, they’re driven by pure instinct. You wouldn’t call a shark that attacks a human ‘evil,’ so neither would you call a Romero-style zombie evil. There as dangerous as a tsunami but equally innocent of malicious intent.”

Night of the Living Id

“Freud described the id as ‘The dark, inaccessible part of us that has no organization, produces no collective will, but only a striving to bring about the satisfaction of instinctual needs.’ That sounds like a zombie to me. At least the reanimated dead we’ve come to know and love over the past four decades. Creatures not driven by any agenda or motivated by any amoral sense, but operating completely on instinct. Zombies are all id, just like newborn children. True, most children aren’t born with the instinct to consume the flesh or brains of their parents, but that’s no justification to label zombies as evil. They’re just a collection of involuntary drives and impulses demanding immediate satisfaction.”—S. G. Browne is author of Breathers: A Zombie’s Lament (Broadway Books, 2009) and Fated (NAL, 2010).

Though, admittedly, it might be hard to remember that when a zombie is chomping on your arm.

“Blameless,” Kier adds, “does not equal ‘harmless.’”

Part of the popularity of zombie and apocalyptic stories stems from the joy of seeing people survive against overwhelming odds. Seeing a great bit of ingenuity is thrilling in any context, but in an apocalyptic scenario the opportunity for ingenuity is boosted to a whole new level. Take the ultimate survival challenge combined with the new level of freedom due to society’s collapse and out pops a whole new horizon of solutions to all manner of problems. Go ahead and take an axe to the staircase. Build a wall out of wrecked cars. Construct catwalks between rooftops. Trap and train the zombies (or aliens, or infected). Nuke a city to eliminate just one person (or creature, or building). Fight to get into prison. Fans of the apocalypse eat up these scenarios that can only really play out in a world that’s already gone to hell.

THE MISUNDERSTOOD MONSTER

Along with the mindless evil we have the misunderstood monster, a creature who is dangerously innocent. Innocent because he, she, or it lacks the emotional maturity or cultural awareness to grasp the concepts of right and wrong or good and bad. Dangerous because they may be equally unaware of their own strength or unable to control their own nature. Yet these monsters differ from the mindless variety because they can think (to a degree) and feel (again, to a degree), and they are often confused, hurt, psychologically damaged, or too alien for their own good.

The classic example is Frankenstein’s monster. He has no true identity; he’s a composite being with a damaged brain. Many literary scholars have debated over whether such a creature would have a soul—though I tend to think so. The possession—or lack thereof—of a soul was never the creature’s issue. It was his damaged brain and awareness of his hideous and unique nature. This was most poignantly portrayed by Boris Karloff in the James Whale movie of 1931. Karloff gave humanity to the creature and highlighted its pitiable state.

Misunderstood Monsters

“I always sympathize with the monster, because the most interesting ones are simply misunderstood when you get right down to it. They really just want one thing: love! All the classics like Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, and the Wolf-man are simply looking for a hug from a lovely gyno-American! I have always wanted Frankenstein’s monster to live, and instead of a little girl with a daisy, I made sure Toxie caught the blind eye of a gorgeous blond bombshell!”—Lloyd Kaufman is president of Troma Films and creator (with Joe Ritter) of the Toxic Avenger.

Universal Pictures made a number of films with a similar theme. In both versions of their take on werewolves, The Wolf Man (1941) and The Wolfman (2010), Larry Talbot is a tragic figure who is by no means evil and is unable to control the violence of the monster that lives beneath his skin. Each morning following the full moon, when Talbot becomes aware of what the werewolf has done, he is torn by remorse. Genuine remorse.

Twas Beauty Killed the Beast

“King Kong was always my favorite. He was taken away from what he knew, his home and life, to a place where he was a monster, a novelty and a tragic victim of his captors. The love story is there to humanize the beast so we can relate better with his loss and solidify the monster to our own perspectives. Most great stories involve a monster who is a hero and a hero who is a monster.”—Doug Schooner is an artist, poet, and animator.

King Kong is another twist. Kong has the intelligence of a great ape, or perhaps a smidge more, but he isn’t a human and cannot reason (we assume) like a human. However, he shows compassion when protecting Anne Darrow from pterodactyls and tyrannosaurs, and he believes he’s protecting her when he breaks out of the New York theater and carries her to the top of the Empire State Building. At the same time, the mayor, the governor, and the flyers from Roosevelt Field are justified in doing what they do to protect the city from the monster. They kill him the way they would kill a lion loose in the streets. Has either character acted with evil? No. The true villain of the piece is Carl Denham, the blowhard show-man who captures Kong and brings him to America. Every death in the movie can be laid at his feet, and yet none of the film versions really paint him as evil. Corrupt, self-important, egocentric…but not evil; yet he shows no remorse for all the deaths he’s caused. It’s weird, and it’s also disturbing.