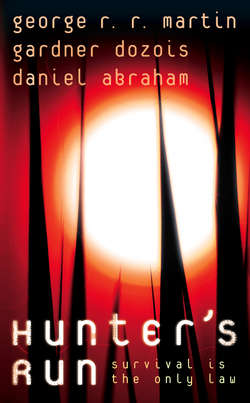

Читать книгу Hunter’s Run - Джордж Р. Р. Мартин - Страница 5

PART ONE

CHAPTER THREE

ОглавлениеIt was a warm day in the Second June. He flew his beat-up old van north across the Fingerlands, the Green-glass country, the river marshes, the Océano Tétrico, heading deep into unknown territory. North of Fiddler’s Jump, the northernmost outpost of the metastasizing human presence on the planet, were thousands of hectares that no one had ever explored, or even thought of exploring, land so far only glimpsed from orbit during the first colony surveys.

The human colony on the planet of São Paulo was only a little more than twenty years old, and the majority of its towns were situated in the subtropic zone of the snaky eastern continent that stretched almost from pole to pole. The colonists were mostly from Brazil and Mexico, with a smattering from Jamaica, Barbados, Puerto Rico, and other Caribbean nations, and their natural inclination was to expand south, into the steamy lands near the equator – they were not effete norteamericanos, after all; they were used to such climates, they knew how to live with the heat, they knew how to farm the jungles, their skins did not sear in the sun. So they looked to the south, and tended to ignore the cold northern territories, perhaps because of an unvocalized common conviction – one anticipated centuries before by the first Spanish settlers in the New World of the Americas – that life was not worth living any place where there was even a remote possibility of snow.

Ramon, however, was part Yaqui, and had grown up in the rugged plateau country of northern Mexico. He liked the hills and white water, and he didn’t mind the cold. He also knew that the Sierra Hueso mountain chain in the northern hemisphere of São Paulo was a more likely place to find rich ore than the flatter country around the Hand or Nuevo Janeiro or Little Dog. The peaks around the Sierra Hueso had been piled up many millions of years before by a collision between continental plates squeezing an ocean out of existence between them; the former seabottom would have been pinched and pushed high into the air along the collision line, and it would be rich in copper and other metals.

Few if any of the muleback prospectors like himself had as yet bothered with the northern lands; pickings were still rich enough down south that the travel time seemed unnecessary to most people. The Sierra Hueso had been mapped from orbit, but no one Ramon knew had ever actually been there, and the territory was still so unexplored that the peaks of the range had not even been individually named. That meant that there were no human settlements within hundreds of miles, and no satellite to relay his network signals this far north; if he got into trouble he would be on his own. He would be one of the first to prospect there, but years would pass, the economic pressure in the south would get higher, and more people would come north, following the charts Ramon had made and sold, interpreting the data he rented out to the corporations and governing bodies. They would follow him like the native scorpion ants – first one, and then a handful, and then countless thousands of small insectoid bodies in the consuming river. Ramon was that first ant, the one driven to risk, to explore. He was a leader not because he chose to be, but because it was his nature to seek distance.

It was better that way, to be the first ant. Although he was reluctant to admit it, he’d finally come to realize that it was better if he worked someplace away from other prospectors. Away from other people. The bigger prospecting cooperatives might have better contracts, better equipment, but they also had more rum and more women. And between those two, Ramon knew, more fighting. He couldn’t trust his own volatile temper, never had been able to. It had held him back for years, the fighting, and the trouble it got him into. Now it had gotten him into trouble that might cost him his life, if they caught him. No, it was better this way – muleback prospecting, just himself and his van.

Besides, he was finding that he liked to be out on his own like this, on a clear day with São Paulo’s big soft sun blinking dimly back at him from rivers and lakes and leaves. He found that he was whistling tunelessly as the endless forests beneath the van slowly changed from blackwort and devilwood to the local conifer-equivalents: iceroot, creeping willow, hierba. At last, there was no one around to bother him. For the first time that day, his stomach had almost stopped hurting.

Almost.

With every hour that passed, every forest and lake that appeared, drew near, and slipped away, the thought of the European he’d killed grew in Ramon’s mind, his presence sharpening pixel by pixel, becoming more real, until he could almost, almost, see him sitting in the copilot’s seat, that stupid look of dumb surprise at his own mortality still stamped on his big pale face – and the more real his ghostly presence became, the deeper Ramon’s hatred for him grew.

He hadn’t hated him back at the El Rey; the man had just been another bastard looking for trouble and finding Ramon. It had happened before more times than he could recall. It was part of how things worked. He came to town, he drank, he and some rabid asshole found each other, and one of them walked away. Maybe it was Ramon, maybe it was the other guy. Rage, yes, rage had something to do with it, but not hatred. Hatred meant you knew a man, you cared about him. Rage lifted you up above everything – morality, fear, yourself. Hatred meant that someone had control over you.

This was the place that usually brought him peace, the outback, the remote territory, the unpeopled places. The tension that came with being around people loosened. In the city – Diegotown or Nuevo Janeiro or any place where too many people came together – Ramon had always felt the press of people against him. The voices just out of earshot, the laughter that might or might not have been directed at him, the impersonal stares of men and women, Elena’s lush body and her uncertain mind; they were why Ramon drank when he was in the city and stayed sober in the field. In the field there was no reason to drink.

But here, where that peace should have been, the European was with him. Ramon would look out into the limitless bowl of the sky, and his mind would turn back to that night at the El Rey, the sudden awed silence of the crowd. The blood pouring from the European’s mouth. His heels drumming against the ground. He checked his maps, and instead of letting his mind run freely across the fissures and plates of the planetary surface, he thought of where the police might go to search for him. He could not let go of what had happened, and the frustration of that was almost as enraging as the guilt itself.

But guilt was for weaklings and fools. Everything would be all right. He would spend his time in the field, communing with the stone and the sky, and when he returned to the city, the European would be last season’s news. Something half remembered and retold in a thousand different versions, none of them true. It was one little death among all the hundreds of millions – natural and otherwise – that happened every year throughout the known universe. The dead man’s absence would be like taking a finger out of water; it wouldn’t leave a hole.

Mountains made a line across the world before him: ice and iron, iron and ice.

Those would be the Sawtooths, which meant that he’d already overflown Fiddler’s Jump. When he checked the navigation transponders, there was no signal. He was gone, out of human contact, off the incomplete communication network of the colony. On his own. He made the adjustments he’d planned, altering his flight path to throw off any human hounds that the law might set after him, but even as he did so, the gesture seemed pointless. He wouldn’t be followed. No one would care.

He set the autopilot, tilted his chair back until it was almost flat as his cot, and, in spite of the reproachful almost-presence of the European, let the miles rolling by beneath him lull him to sleep.

When he woke, the even-grander peaks of the Sierra Hueso range were thrusting above the horizon, and the sun was getting low in the sky, casting shadows across the mountain faces. He switched off the autopilot and brought the van to rest in a rugged upland meadow along the southern slopes of the range. After the bubbletent had been set up, the last perimeter alarm had been placed, and a fire pit dug and dry wood scavenged to fill it, Ramon walked to the edge of a small nearby lake. This far north, it was cold even in summer, and the water was chill and clear; the biochip on his canteen reported nothing more alarming than trace arsenic. He gathered a double-handful of sug beetles and took them back to his camp. Boiled, they tasted of something midway between crab and lobster, and the gray stone-textured shells took on an unpredictable rainbow of iridescent colors when the occupying flesh was sucked free. It was easy to live off this country, if you knew how. In addition to sug beetles and other scavengable foodstuffs, there was water to hand and there would be easy game nearby if he chose to stay longer than the month or two his van’s supplies would support. He might stay until the equinox, depending on the weather. Ramon even found himself wondering how difficult it would be to winter over here in the north. If he dropped south to Fiddler’s Jump for fuel and slept in the van for the coldest months …

After he’d eaten, he lit a cigarette, lay back, and watched the mountains darken with the sky. A flapjack moved against the high clouds, and Ramon rose up on one elbow to watch it. It rippled its huge, flat, leathery body, sculling with its wing tips, seeking a thermal. Its ridiculous squeaky cry came clearly to him across the gulfs of air. They were almost level; it would be evaluating him now, deciding that he was much too big to eat. The flapjack tilted and slid away and down, as though riding a long invisible slope of air, off to hunt squeakers and grasshoppers in the valley below. Ramon watched the flapjack until it dwindled to the size of a coin, glowing bronze in the failing light.

‘Good hunting!’ he called after it, and then smiled. Good hunting for both of them, eh? As the last of the daylight touched the top of the ridgeline on the valley’s eastern rise, Ramon caught sight of something. A discontinuity in the stone. It wasn’t the color or the epochal striations, but something more subtle. Something in the way the face of the mountain sat. It wasn’t alarming as much as interesting. Ramon put a mental flag there; something strange, worth investigating in the morning.

He lounged by the fire for a few moments while the night gathered completely around him and the alien stars came out in their chill, blazing armies. He named the strange constellations the people of São Paulo had drawn in the sky to replace the old constellations of Earth – the Mule, the Stone Man, the Cactus Flower, the Sick Gringo – and wondered (he’d been told, but had forgotten) which of them had Earth’s own sun twink ling in it as a star? Then he went to bed and to sleep, dreaming that he was a boy again in the cold stone streets of his hilltop pueblo, sitting on the roof of his father’s house in the dark, a scratchy wool blanket wrapped around him, trying to ignore the loud, angry voices of his parents in the room below, searching for São Paulo’s star in the winter sky.