Читать книгу Fire and Blood - Джордж Р. Р. Мартин - Страница 6

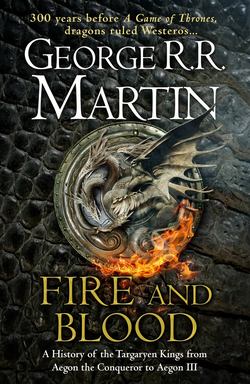

Fire & Blood

Being a History of the Targaryen Kings of Westeros

Three Heads Had the Dragon

Governance Under King Aegon I

ОглавлениеAegon I Targaryen was a warrior of renown, the greatest Conqueror in the history of Westeros, yet many believe his most significant accomplishments came during times of peace. The Iron Throne was forged with fire and steel and terror, it is said, but once the throne had cooled, it became the seat of justice for all Westeros.

The reconciliation of the Seven Kingdoms to Targaryen rule was the keystone of Aegon I’s policies as king. To this end, he made great efforts to include men (and even a few women) from every part of the realm in his court and councils. His former foes were encouraged to send their children (chiefly younger sons and daughters, as most great lords desired to keep their heirs close to home) to court, where the boys served as pages, cupbearers, and squires, the girls as handmaidens and companions to Aegon’s queens. In King’s Landing, they witnessed the king’s justice at first hand, and were urged to think of themselves as leal subjects of one great realm, not as westermen or stormlanders or northmen.

The Targaryens also brokered many marriages between noble houses from the far ends of the realm, in hopes that such alliances would help tie the conquered lands together and make the seven kingdoms one. Aegon’s queens, Visenya and Rhaenys, took a special delight in arranging these matches. Through their efforts, young Ronnel Arryn, Lord of the Eyrie, took a daughter of Torrhen Stark of Winterfell to wed, whilst Loren Lannister’s eldest son, heir to Casterly Rock, married a Redwyne girl from the Arbor. When three girls, triplets, were born to the Evenstar of Tarth, Queen Rhaenys arranged betrothals for them with House Corbray, House Hightower, and House Harlaw. Queen Visenya brokered a double wedding between House Blackwood and House Bracken, rivals whose history of enmity went back centuries, matching a son of each house with a daughter of the other to seal a peace between them. And when a Rowan girl in Rhaenys’s service found herself with child by a scullion, the queen found a knight to marry her in White Harbor, and another in Lannisport who was willing to take on her bastard as a fosterling.

Though none doubted that Aegon Targaryen was the final authority in all matters relating to the governance of the realm, his sisters Visenya and Rhaenys remained his partners in power throughout his reign. Save perhaps for Good Queen Alysanne, the wife of King Jaehaerys I, no other queen in the history of the Seven Kingdoms ever exercised as much influence over policy as the Dragon’s sisters. It was the king’s custom to bring one of his queens with him wherever he traveled, whilst the other remained at Dragonstone or King’s Landing, oft as not seated on the Iron Throne, ruling on whatever matters came before her.

Though Aegon had designated King’s Landing as his royal seat and installed the Iron Throne in the Aegonfort’s smoky longhall, he spent no more than a quarter of his time there. Full as many of his days and nights were spent on Dragonstone, the island citadel of his forebears. The castle below the Dragonmont had ten times the room of the Aegonfort, with considerably more comfort, safety, and history. The Conqueror was once heard to say that he even loved the scent of Dragonstone, where the salt air always smelled of smoke and brimstone. Aegon spent roughly half the year at his two seats, dividing his time between them.

The other half he devoted to an endless royal progress, taking his court from one castle to another, guesting with each of his great lords in turn. Gulltown and the Eyrie, Harrenhal, Riverrun, Lannisport and Casterly Rock, Crakehall, Old Oak, Highgarden, Oldtown, the Arbor, Horn Hill, Ashford, Storm’s End, and Evenfall Hall had the honor of hosting His Grace many times, but Aegon could and would turn up almost anywhere, sometimes with as many as a thousand knights and lords and ladies in his train. He journeyed thrice to the Iron Islands (twice to Pyke and once to Great Wyk), spent a fortnight at Sisterton in 19 AC, and visited the North six times, holding court thrice in White Harbor, twice at Barrowton, and once at Winterfell on his very last royal progress in 33 AC.

“It is better to forestall rebellions than to put them down,” Aegon famously said, when asked the reason for his journeys. A glimpse of the king in all his power, mounted on Balerion the Black Dread and attended by hundreds of knights glittering in silk and steel, did much to instill loyalty in restless lords. The smallfolk needed to see their kings and queens from time to time as well, the king added, and know that they might have the chance to lay their grievances and concerns before him.

And so they did. Much of every royal progress was given over to feasts and balls and hunts and hawking, as every lord attempted to outdo the others in splendor and hospitality, but Aegon also made a point of holding court wherever he might travel, whether from a dais in some great lord’s castle or a mossy stone in a farmer’s field. Six maesters traveled with him, to answer any questions he might have on local law, customs, and history, and to make note of such decrees and judgments as His Grace might hand down. A lord should know the land he rules, the Conqueror later told his son Aenys, and through his travels Aegon learned much and more about the Seven Kingdoms and its peoples.

Each of the conquered kingdoms had its own laws and traditions. King Aegon did little to interfere with those. He allowed his lords to continue to rule much as they always had, with all the same powers and prerogatives. The laws of inheritance and succession remained unchanged, the existing feudal structures were confirmed, lords both great and small retained the power of pit and gallows on their own land, and the privilege of the first night wherever that custom had formerly prevailed.

Aegon’s chief concern was peace. Before the Conquest, wars between the realms of Westeros were common. Hardly a year passed without someone fighting someone somewhere. Even in those kingdoms said to be at peace, neighboring lords oft settled their disputes at swordpoint. Aegon’s accession put an end to much of that. Petty lords and landed knights were now expected to take their disputes to their liege lords and abide by their judgments. Arguments between the great houses of the realm were adjudicated by the Crown. “The first law of the land shall be the King’s Peace,” King Aegon decreed, “and any lord who goes to war without my leave shall be considered a rebel and an enemy of the Iron Throne.”

King Aegon also issued decrees regularizing customs, duties, and taxes throughout the realm, whereas previously every port and every petty lord had been free to exact however much they could from tenants, smallfolk, and merchants. He also proclaimed that the holy men and women of the Faith, and all their lands and possessions, were to be exempt from taxation, and affirmed the right of the Faith’s own courts to try and sentence any septon, Sworn Brother, or holy sister accused of malfeasance. Though not himself a godly man, the first Targaryen king always took care to court the support of the Faith and the High Septon of Oldtown.

King’s Landing grew up around Aegon and his court, on and about the three great hills that stood near the mouth of the Blackwater Rush. The highest of those hills had become known as Aegon’s High Hill, and soon enough the lesser hills were being called Visenya’s Hill and the Hill of Rhaenys, their former names forgotten. The crude motte-and-bailey fort that Aegon had thrown up so quickly was neither large enough nor grand enough to house the king and his court, and had begun to expand even before the Conquest was complete. A new keep was erected, all of logs and fifty feet high, with a cavernous longhall beneath it, and a kitchen, made of stone and roofed with slate in case of fire, across the bailey. Stables appeared, then a granary. A new watchtower was raised, twice as tall as the older one. Soon the Aegonfort was threatening to burst out of its walls, so a new palisade was raised, enclosing more of the hilltop, creating space enough for a barracks, an armory, a sept, and a drum tower.

Below the hills, wharves and storehouses were rising along the riverbanks, and merchants from Oldtown and the Free Cities were tying up beside the longships of the Velaryons and Celtigars, where only a few fishing boats had previously been seen. Much of the trade that had gone through Maidenpool and Duskendale was now coming to King’s Landing. A fish market sprung up along the riverside, a cloth market between the hills. A customs house appeared. A modest sept opened on the Blackwater, in the hull of an old cog, followed by a stouter one of daub-and-wattle on the shore. Then a second sept, twice as large and thrice as grand, was built atop Visenya’s Hill, with coin sent by the High Septon. Shops and homes sprouted like mushrooms after a rain. Wealthy men raised walled manses on the hillsides, whilst the poor gathered in squalid hovels of mud and straw in the low places between.

No one planned King’s Landing. It simply grew … but it grew quickly. At Aegon’s first coronation, it was still a village squatting beneath a motte-and-bailey castle. By his second, it was already a thriving town of several thousand souls. By 10 AC, it was a true city, almost as large as Gulltown or White Harbor. By 25 AC, it had outgrown both to become the third most populous city in the realm, surpassed only by Lannisport and Oldtown.

Unlike its rivals, however, King’s Landing had no walls. It needed none, some of its residents were known to say; no enemy would ever dare attack the city so long as it was defended by the Targaryens and their dragons. The king himself might have shared these views originally, but the death of his sister Rhaenys and her dragon, Meraxes, in 10 AC and the attacks upon his own person undoubtedly gave him cause …

And in the 19th year After the Conquest, word reached Westeros of a daring raid in the Summer Isles, where a pirate fleet had sacked Tall Trees Town and carried off a thousand women and children as slaves, along with a fortune in plunder. The accounts of the raid greatly troubled the king, who realized that King’s Landing would be similarly vulnerable to any enemy shrewd enough to fall upon the city when he and Visenya were elsewhere. Accordingly, His Grace ordered the construction of a ring of walls about King’s Landing, as high and strong as those that protected Oldtown and Lannisport. The task of building them was conferred upon Grand Maester Gawen and Ser Osmund Strong, the Hand of the King. To honor the Seven, Aegon decreed that the city would have seven gates, each defended by a massive gatehouse and defensive towers. Work on the walls began the next year and continued until 26 AC.

Ser Osmund was the king’s fourth Hand. His first had been Lord Orys Baratheon, his bastard half-brother and companion of his youth, but Lord Orys was taken captive during the Dornish War and suffered the loss of his sword hand. When ransomed back, his lordship asked the king to be relieved of his duties. “The King’s Hand should have a hand,” he said. “I will not have men speaking of the King’s Stump.” Aegon next called on Edmyn Tully, Lord of Riverrun, to take up the Handship. Lord Edmyn served from 7–9 AC, but when his wife died in childbed, he decided that his children had more need of him than the realm, and begged leave to return to the riverlands. Alton Celtigar, Lord of Claw Isle, replaced Tully, serving ably as Hand until his death from natural causes in 17 AC, after which the king named Ser Osmund Strong.

Grand Maester Gawen was the third in that office. Aegon Targaryen had always kept a maester on Dragonstone, as his father and father’s father had before him. All the great lords of Westeros, and many lesser lords and landed knights, relied upon maesters trained in the Citadel of Oldtown to serve their households as healers, scribes, and counselors, to breed and train the ravens who carried their messages (and write and read those messages for lords who lacked those skills), help their stewards with the household accounts, and teach their children. During the Conquest, Aegon and his sisters each had a maester serving them, and afterward the king sometimes employed as many as half a dozen to deal with all the matters brought before him.

But the wisest and most learned men in the Seven Kingdoms were the archmaesters of the Citadel, each of them the supreme authority in one of the great disciplines. In 5 AC, King Aegon, feeling that the realm might benefit from such wisdom, asked the Conclave to send him one of their own number to advise and consult with him on all matters relating to the governance of the realm. Thus was the office of Grand Maester created, at King Aegon’s request.

The first man to serve in that capacity was Archmaester Ollidar, keeper of histories, whose ring and rod and mask were bronze. Though exceptionally learned, Ollidar was also exceptionally old, and he passed from this world less than a year after taking up the mantle of Grand Maester. To fill his place, the Conclave selected Archmaester Lyonce, whose ring and rod and mask were yellow gold. He proved more robust than his predecessor, serving the realm until 12 AC, when he slipped in the mud, broke his hip, and died soon thereafter, whereupon Grand Maester Gawen was elevated.

The institution of the king’s small council did not come into its full bloom until the reign of King Jaehaerys the Conciliator, but that is not to suggest that Aegon I ruled without the benefit of counsel. He is known to have consulted often with his various Grand Maesters, and his own household maesters as well. On matters relating to taxation, debts, and incomes, he sought the advice of his masters of coin. Though he kept one septon at King’s Landing and another at Dragonstone, the king more oft wrote to the High Septon of Oldtown on religious issues, and always made a point of visiting the Starry Sept during his yearly circuit. More than any of these, King Aegon relied upon the King’s Hand, and of course upon his sisters, the Queens Rhaenys and Visenya.

Queen Rhaenys was a great patron to the bards and singers of the Seven Kingdoms, showering gold and gifts on those who pleased her. Though Queen Visenya thought her sister frivolous, there was a wisdom in this that went beyond a simple love of music. For the singers of the realm, in their eagerness to win the favor of the queen, composed many a song in praise of House Targaryen and King Aegon, and then went forth and sang those songs in every keep and castle and village green from the Dornish Marches to the Wall. Thus was the Conquest made glorious to the simple people, whilst Aegon the Dragon himself became a hero king.

Queen Rhaenys also took a great interest in the smallfolk, and had a special love for women and children. Once, when she was holding court in the Aegonfort, a man was brought before her for beating his wife to death. The woman’s brothers wanted him punished, but the husband argued that he was within his lawful rights, since he had found his wife abed with another man. The right of a husband to chastise an erring wife was well established throughout the Seven Kingdoms (save in Dorne). The husband further pointed out that the rod he had used to beat his wife was no thicker than his thumb, and even produced the rod in evidence. When the queen asked him how many times he had struck his wife, however, the husband could not answer, but the dead woman’s brothers insisted there had been a hundred blows.

Queen Rhaenys consulted with her maesters and septons, then rendered her decision. An adulterous wife gave offense to the Seven, who had created women to be faithful and obedient to their husbands, and therefore must be chastised. As god has but seven faces, however, the punishment should consist of only six blows (for the seventh blow would be for the Stranger, and the Stranger is the face of death). Thus the first six blows the man had struck had been lawful … but the remaining ninety-four had been an offense against gods and men, and must be punished in kind. From that day forth, the “rule of six” became a part of the common law, along with the “rule of thumb.” (The husband was taken to the foot of the Hill of Rhaenys, where he was given ninety-four blows by the dead woman’s brothers, using rods of lawful size.)

Queen Visenya did not share her sister’s love of music and song. She was not without humor, however, and for many years kept her own fool, a hirsute hunchback called Lord Monkeyface whose antics amused her greatly. When he choked to death on a peach pit, the queen acquired an ape and dressed it in Lord Monkeyface’s clothing. “The new one is cleverer,” she was wont to say.

Yet there was darkness in Visenya Targaryen. To most of the world, she presented the grim face of a warrior, stern and unforgiving. Even her beauty had an edge to it, her admirers said. The oldest of the three heads of the dragon, Visenya was to outlive both of her siblings, and it was rumored that in her later years, when she could no longer wield a sword, she delved into the dark arts, mixing poisons and casting malign spells. Some even suggest that she might have been a kinslayer and a kingslayer, though no proof has ever been offered to support such calumnies.

It would be a cruel irony if true, for in her youth no one did more to protect the king. Visenya twice wielded Dark Sister in Aegon’s defense when he was set upon by Dornish cutthroats. Suspicious and ferocious by turns, she trusted no one but her brother. During the Dornish War, she took to wearing a shirt of mail night and day, even under her court clothes, and urged the king to do the same. When Aegon refused, Visenya grew furious. “Even with Blackfyre in your hand, you are only one man,” she told him, “and I cannot always be with you.” When the king pointed out that he had guardsmen around him, Visenya drew Dark Sister and slashed him across the cheek so quickly the guards had no time to react. “Your guards are slow and lazy,” she said. “I could have killed you as easily as I cut you. You require better protection.” King Aegon, bleeding, had no choice but to agree.

Many kings had champions to defend them. Aegon was the Lord of the Seven Kingdoms; therefore, he should have seven champions, Queen Visenya decided. Thus did the Kingsguard come into being; a brotherhood of seven knights, the finest in the realm, cloaked and armored all in purest white, with no purpose but to defend the king, giving up their own lives for his if need be. Visenya modeled their vows on those of the Night’s Watch; like the black-cloaked crows of the Wall, the White Swords served for life, surrendering all their lands, titles, and worldly goods to live a life of chastity and obedience, with no reward but honor.

So many knights came forward to offer themselves as candidates for the Kingsguard that King Aegon considered holding a great tourney to determine which of them was the most worthy. Visenya would not hear of it, however. To be a Kingsguard knight required more than just skill at arms, she pointed out. She would not risk placing men of uncertain loyalty about the king, regardless of how well they performed in a melee. She would choose the knights herself.

The champions she selected were young and old, tall and short, dark and fair. They came from every corner of the realm. Some were younger sons, others the heirs of ancient houses who gave up their inheritances to serve the king. One was a hedge knight, another bastard born. All of them were quick, strong, observant, skilled with sword and shield, and devoted to the king.

These are the names of Aegon’s Seven, as written in the White Book of the Kingsguard: Ser Richard Roote; Ser Addison Hill, Bastard of Cornfield; Ser Gregor Goode; Ser Griffith Goode, his brother; Ser Humfrey the Mummer; Ser Robin Darklyn, called Darkrobin; and Ser Corlys Velaryon, Lord Commander. History has confirmed that Visenya Targaryen chose well. Two of her original seven would die protecting the king, and all would serve with valor to the end of their lives. Many brave men have followed in their footsteps since, writing their names in the White Book and donning the white cloak. The Kingsguard remains a synonym for honor to this day.

Sixteen Targaryens followed Aegon the Dragon to the Iron Throne, before the dynasty was at last toppled in Robert’s Rebellion. They numbered amongst them wise men and foolish, cruel men and kind, good men and evil. Yet if the dragon kings are considered solely on the basis of their legacies, the laws and institutions and improvements they left behind, the name of King Aegon I belongs near the top of the list, in peace as well as war.