Читать книгу Where To? - Dmitry Samarov - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеABOUT ALL THIS ART

My first book, Hack: Stories from a Chicago Cab, took a look at a driver’s typical work week. This one, which begins with my first fare as a 23-year-old cab driver in Boston and ends with my last fare as a 41-year-old cab driver in Chicago, is more of a summing up of all my time behind the wheel. Between the first and last rides, the episodes are arranged thematically rather than chronologically in an attempt to give a sense of the breadth of experiences in my twelve years on the job. There are still many small moments—watching and listening to people is at the root of everything I do—but unlike the first book there’s a beginning and an end and thus an opportunity to look back.

I never intended to write a thing.

When I decided to write about driving a cab, I needed a way in. That way in was through drawing. I don’t ever remember not drawing—it’s how I talk to the world—so, although it’s probably not how most people would ease their way into writing a book, I didn’t know of any other way.

The pictures I’ve included are culled from posts from the last two years of my blog, Chicago Hack, as well as the Hack zine from 2000, and sketches I did in the cab over the years while waiting at airports and cabstands. Drawing and painting are still my surest way into writing. While I’m finishing a picture, the phrases I’ll use crystallize in my mind. And as I’m writing, I’ll look back at the artwork to remind myself of the scene I’m trying to render in words.

The artwork in these pages runs the gamut from on-site, observed sketches to atmospheric, remembered city scapes to flat-out caricatures. Almost every piece of writing I’ve ever done has started with a drawn or painted image of some kind. The kind of picture it is depends on what I’m trying to write. Sometimes it complements the text, other times it serves as a counterpoint, but in every instance one can’t exist without the other.

Because of the prohibitive costs of color printing, I restricted the illustrations for these cab stories to black-and-white. Some were done with ballpoint pen or charcoal, but most of the art in this book was done with Sumi ink. At this point, I’ve been working with it for about 17 years. It has the richest tonal range of any ink I’ve tried.

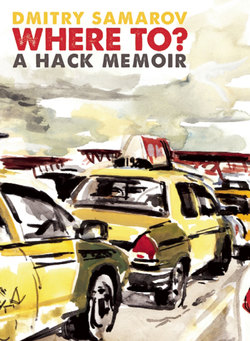

The painting on the cover of this book is O’Hare Taxi Staging Area #1. It’s the first of a series of gouache paintings I did at Chicago’s airports while waiting to be dispatched to the terminals to pick up fares. The challenge was to finish the painting before my subject matter left. The taxi staging area is a big parking lot where cabs line up in rows. Once the starter radios for cabs, the rows move out. At the outside, I had about three or four hours to get down in brushstrokes as much of what I saw as I could. Out of the 40 or so of these that I attempted, about ten or fifteen came out okay.

O’Hare #23 (pg. 7) is one of the dozens of ballpoint pen sketches I did over the years at the airport. These sketches were never meant to be preparatory studies for more finished work. They were always an end in themselves. I’ve chosen to use several of them throughout this book to give a sense of what cab drivers spend much of their day looking at: other cabs.

Dispatch Squawk (pg. 11) was one of my first attempts to illustrate what it was like to be a cab driver. It was painted for Hack #1 in 2000. The words and numbers shooting out of the two-way radio were meant to convey the nonstop cacophony throughout the long shifts.

Empty Lot (pg. 19) was one of the first times I used Google Streetview as a visual reference for an illustration. I needed to see one of the places I was trying to write about that was no longer there and sure enough, Google had a recent record of it. This particular lot was on California Avenue, just past the Kennedy Expressway, the former home of the worst cab garage from which I had the misfortune of renting a vehicle.

Cabbies #3 (pg. 32) was done while sitting through one of the interminable refresher courses the city requires drivers to take. I’ve done sketches of classmates and teachers ever since elementary school. For most people, sitting in a classroom means taking notes, listening, or sleeping; for me it has always been time for drawing.

Sometimes I needed a picture that wasn’t that specific, but more of a general notion of what I was trying to write about. Business (pg. 45) depicts a series of office types with roller suitcases. It’s the sort of sight that’s ubiquitous in any city, but by taking the time to paint I was able to focus on the words I needed to say what I needed to say.

Blizzard (pg. 61) gave me a way to communicate the feeling of being enveloped in snow in a way that words could not. When writing works it’s able to put you in a particular place, but oftentimes, a few accurate ink marks will do it even better.

When two 20-year-olds spend a whole ride talking about Charles Bronson (pg. 85), it made what I was going to paint a no-brainer.

Many of the portraits of passengers—like Braggart (pg. 106)—were done from memory and, often, not exactly meant to flatter. But others—like Tony Fitzpatrick (pg. 152)—were done from life and were meant to depict people the best I could. It all depended on the tenor of the ride and what I was trying to tell about the person. Some were character assassinations while others were faithful, straightforward depictions. I met all kinds and tried to render as full a spectrum as I could.

My first impulse has always been and will always be to reach for the brush before the pen. The words in this book would never have been written if I didn’t draw or paint them first. I take the world in through my eyes best and there would never be any words without these pictures.