Читать книгу Vasyl Stus: Life in Creativity - Dmytro Stus - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

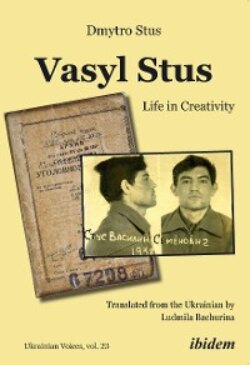

Preliminary Remarks

ОглавлениеVasyl Stus.

Poet.

Human rights activist.

Man.

Friend. Husband. Father. Prisoner. Philosopher. Acquaintance. Beloved. Known and unknown. Politician and anti-politician at the same time. Alive and long dead—from the viewpoint of human life, but not in historical perspective.

Who are You? Why, for several decades after Your death, has Your figure been attracting attention, provoking resistance from some and true admiration from others? Why are You clambering up and falling down at the same time?

Why, despite such a significant interest in You, do the following words by Mykola Ryabchuk seem both so close to the truth and at the same time unrelated to Your texts: “Vasyl Stus, demythologized by young critics, has much less of a chance of becoming a Ukrainian popular cultural hero than his mythologized populist hypostasis may suggest”?1

And what made almost 100,000 people pour into the frosty streets of Kyiv on November 19, 1989, to pay their last respects to You, who had remained unknown even to many writers. (People have often confessed to me that they learned about Vasyl Stus on that day. But no famous person, as far as I know, dared to write about it).

For some reason, the fate of Vasyl Stus has strengthened with time and still serves as a litmus test of authenticity, proving once again that a person, against all odds, is still able to overcome fear and become worthy of his calling. I am sure that if the officials of the Ukrainian Communist Party Central Committee and KGB, who decided in 1972 to charge the poet, had realized that they were creating a national myth of the indomitable Ukrainian spirit, they would never have brought the case, which was completely made up and “tied” to the confrontation between Petro Shelest and Leonid Brezhnev,2 to court.

But that’s exactly what happened …

At that time, the same Fate—combining the instinct of self-preservation and the desire for self-immolation, providence, and faith, everyday life and holiday—led Stus’ parents to move from starving and despairing Rakhnivka to working Stalino. And the same Fate drove Vasyl from there to Kyiv, a city that repeatedly rejected him as a foreign body before honoring him as a hero after his death. Fate tested the poet in new ways and by new trials, but he, divining its commands, found in himself the strength and will to proudly accept the challenge. This is how the mystery of Vasyl Stus’ life was created, according to whose internal logic, against all odds, he had to self-actualize to the very maximum, to “expend” himself. A constant readiness to maximally fill the moment of life, whatever the circumstances, makes it possible to speak today of the phenomenon of Vasyl Stus—a man, a poet, a husband, a father, a son, known and unknown, good and …

Yet this book is not only about Vasyl Stus. After all, whoever he was, whatever he created of himself, his dependence on the socio-cultural and political conditions under which he happened to live was so great that to understand the true motives of the poet’s actions, it would be necessary to encompass his social history. Then what could we say about Vasyl Stus, whose personality would thus be subordinated to the “common, to social life, in all its concrete historical connections and indirectness”?3

In some of his manifestations, this “esthete, aristocrat, Westerner, this admirer of the esoteric Rilke and anyone hostile to what is ‘ours,’ this foreign spirit”4 paradoxically proved much closer to the established tradition of subordinating the Ukrainian artist to the pains and problems of his people than to any high aesthetic detachment from political discourse (the latter, however, does occupy an extremely important place in Stus’ poetic world). The poet voluntarily consigned the Word to the struggle for the preservation of Ukraine’s national dignity and tradition. “If life were better, I would not write poetry, but would work on the land,”5 he wrote in the preface to the collection Zymovi Dereva (Winter Trees). And this was not a pose. It was rather a conscious choice and the expression of a readiness to form part of a great national tree.6

In these circumstances, the trends and tendencies of literary fashion, which occupy an important place in the formal aspect of the poet’s work, are always assigned a secondary, subordinate function.7 “The main thing is not to betray the truth of life,” Vasyl Stus used to say.

Given this choice (today is the pathetic cliché is that of “serving the interests of the people”), it is not surprising that Vasyl Stus entered the history of Ukrainian literature and culture not thanks to his poems, but, as it were, only with their substantial support. And when, in the mid-1970s, his poems, as insightfully recited by Nadiia Svitlychna, started to be heard quite often on Radio Liberty, behind them there was the image of a fighter against the system, a man who for many listeners was an example of inviolability.

In this way, complementing and opposing each other, the works and biography of Vasyl Stus continue to exist today. The writer, whose works organically combine elements of populism, and of the modern and postmodern,8 in real life appears to be a post-sixtier,9 a dissident who, “guided by personal responsibility … for the fate of the whole nation,” decided that it was not only possible but necessary “to oppose the authorities’ violence by adopting a position of civil disobedience.”10 Strict adherence to this position through his whole life paradoxically brought him closer to and, at the same time, distanced him from the sixtiers’ movement and its ideas. Vasyl Stus was well aware that his path guaranteed neither career success nor material benefits. It was a path to nowhere; nevertheless, he recklessly offered himself for the defense of national and human dignity: “Fate has given me a sign—I bravely follow its call. For I want to be worthy of the native people, who will be born tomorrow, having thrown off the shame of age-old languishing. And in that nation, I will achieve immortality!”11

To follow this path with dignity, it was necessary not only to learn to endure moral and physical torture and humiliation, to multiply the copies of his works, which were destroyed by civil servants at the first opportunity; it was necessary not just to harden and accept separation from family and friends; but also to create an inner world that would allow him to feel confidence and not despair under any circumstances. Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska describes this as “self-exploration.” a quote (or is it a term?) borrowed from Vasyl Stus himself.12

The ability to balance the demands of his inner world and his actions—“with/without dignity”—at a sky-high height, in the historical conditions of the second half of the twentieth century, allowed the poet to withstand all the trials that befell him.

How was his inner world formed, out of which not only poems and works, but—perhaps even more significantly—Stus’ style of life grew, a style described by the poet’s contemporaries as an inability to pass by someone else in pain and despair?

It would seem that it is this openness to pain and suffering that makes the poet’s figure either all-admirable or all-repulsive: no one is indifferent—there is either full recognition and esteem or else utter rejection and denial of this way of life. Given such polarization, it seems possible to see Vasyl Stus’ personality at the intersection of those lines of force that transform a man of the crowd (an ordinary man) into a “man with a biography.” In this regard, Yuri Lotman says that “not everyone who lives in this society has the right to a biography.” After all, each type of culture “forms its own models of ‘people with biographies’ and ‘people without biographies’ ... each culture creates in its ideal model a type of person whose behavior is entirely determined by the system of cultural codes and a person who has a certain freedom of choice for his own behavior model.”13

A striking biography is always a “breaking out” of the ordinary, a violation of given canons, the creation of one’s own honor code, and atypical behavioral conduct, recognized to be socially significant to the extent that the latter serves as an example for other people to define their life strategies. The creation and formation of a person with a proud and independent profile is a much more complicated affair than any literary work. After all, literature is, in the first place, an attempt to comprehend the world by artistic means. Instead, life creation is the creation of oneself, one’s destiny, and thus the world around oneself. And this struggle of the individual to have the right to -actualize, in some cases, actually affects the existing state of society, causing a greater or lesser reaction (transformation, modification) of the latter. And here, in this preface, we use lofty words, but only by using such high registers of contradiction can we speak about Vasyl Stus.

The poet’s inner desire for self-actualization naturally coincided with the clear fixation by the Soviet and Ukrainian intelligentsia, in the first decades of the postwar period, on the philosophical ideas of existentialism, which were perceived by many unbelieving intellectuals as the only possible alternative to the doctrine of Marxism-Leninism.

Only a few people were lucky enough to buy, in the original, the theoretical works even of those authors relatively loyal to the USSR, like Karl Jaspers, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Gabriel Marcel, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus (translations were not even contemplated). Therefore, the fundamental understanding of this philosophical trend was formed by “husking” the grains of meaning from the groundless criticism of the existentialists by Marxist philosophers. Admittedly, this did not provide the opportunity to form a clear idea of existentialism as a philosophical trend; instead, it allowed anyone interested to add his own individual ideas about what existentialism might be. And the fact that existentialism proclaimed human individuality as the highest value, and connected the existence of the world with everyone’s self-actualization, made this philosophical doctrine the most influential in the formation of not only the young Vasyl Stus but of many people who entered upon life in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

To a certain extent, it was his imagined and individually supplemented existentialism that helped Vasyl Stus start a concentrated effort to create an inner, real self, one of whom he would not be ashamed. In addition, the idea of living every day “on the edge,” between life and death, “at the maximum,” was very close to Stus’ psychological type. That is why the poet finally managed to rid himself of the dominating influence of existentialist ideas only in the early 1970s. As Ivan Dziuba rightly remarks, Vasyl Stus outgrows his existential worldview, opening it “into experiencing the fate of his people and belonging to them, into a feat for them.”14

The process of the formation of Vasyl Stus’ personality actually finished on the eve of his arrest in 1972. The rest was simple and clear. Only one thing remained unclear: will you, Vasyl Stus, like millions of your predecessors, be able to pay the inhuman price? A decade-long fee for the right to be the one he wished, to complement the unfolding horizontal with a rapidly growing vertical.

Working on this book, I often caught myself thinking that the poet felt his destiny too early, and some of his actions before 1972 strangely resonated with the future. Having no rational explanation for this temporal rupture (“nonlinearity”), I decided to start the book with his reburial, when Vasyl Stus returned to Ukraine both as a creator and as a man with a biography. This was the beginning of his “life after death,” the point that drew attention to his figure in his homeland. For him, this meant achieving absolute success, because all his life he sought to be interesting to his people.

I hope that Vasyl Stus: Life in Creativity will be only the first attempt to comprehend the mystery of Vasyl Stus’ life. And that more thorough and interesting works in this direction will appear after its release. I have simply tried to collect and systematize what I regard as the most important material. And if it helps someone open the “door” to the secret of the life and work of Vasyl Stus, then my ten-year labor is not in vain.

1 Mykola Riabchuk, “‘Nebizh Rilke, syn Tarasa’ (Vasyl Stus),” in Heroi ta znamenytosti v ukrainskii kulturi, ed. and compil. Oleksandr Hrytsenko (Kyiv: UTsKD, 1999), 231.

2 For more details see Mikhail Kheifets, Izbrannoe, Vol. 3: Ukrainskiie siluety. Voennoplennyi sekretar’ (Kharkiv: Folio, 2000), 26–28.

3 Dmitry Blagoi, “Problemy postroeniia nauchnoi biografii Pushkina,” Literaturnoe nasledstvo, Vol. 16/18 (Moscow, 1934): 270. See also I. Ya. Losievskii, “Nauchnaia biografiia pisatelia: problemy interpretatsii i tipologii” (Kharkiv: Krok, 1998), 22.

4 Riabchuk, “‘Nebizh Rilke, syn Tarasa’ (Vasyl Stus),” 232.

5 Vasyl Stus, “Dvoie sliv chytachevi,” in his Tvory, 4 vols, 6 books (Lviv: Prosvita, 1994–1999), Vol. 1, Book 1: 42.

6 It is with the living tree that the poet most often associated the nation, the people, and tradition. See, in particular, his programmatic works: The Broken Evening Branch Is Swaying…, We Are Circling Around the Trunk…, etc.

7 In a way this confirms the formation of the traditional, rather than modern, discourse around Stus’ work. See, in particular, “‘Stusivs’ki chytannia’,” Slovo i chas, No. 7 (1998): 17–28 (papers by Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Eleonora Solovei, and Mykhailo Naienko; No. 8 (1998): 62–70 (papers by Mykola Bondar, Halyna Burlaka, Mykola Kodak, Viktoriia Plaksina, and Dmytro Stus); as well as the following articles: Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, “Poet,” in Vasyl Stus, Tvory, Vol. 1, Book 1: 7–38; Kotsiubynska, “Fenomen Stusa,” Suchasnist’, No. 9 (1991): 26–35; Mykola Zhulynsky, “Vasyl Stus, 1938–1985,” Literaturna Ukraina, April 19, 1990; Yuri Shevelyov, “Trunok i trutyzna: Pro Palimpsesty Vasylia Stusa,” Vasyl Stus u zhytti, tvorchosti, spohadakh ta otsinkakh suchasnykiv, compil. and ed. Osyp Zinkevych and Mykola Frantsuzhenko (Baltimore and Toronto: Smoloskyp, 1987), 368–401, etc. All of these authors in one way or another comprehend the figure of Vasyl Stus primarily in the traditional Ukrainian context, barely indicating a direction of possible intertextual and comparative studies. They are opposed by a small group of researchers of a more modern cast, as it were, whose texts are mostly collected in the book Stus yak tekst, ed. Marko Pavlyshyn (Melburn: Department of Slavic Studies, Monash University, 1992) (articles by Tamara Hundorova, “Fenomen Stusovoho ‘zhertvoslova’,” pp 1–29, and Marko Pavlyshyn, “Kvadratura kruha: prolehomeny do otsinky Vasylia Stusa,” 31–52). The figure and works of Vasyl Stus are perceived through a largely non-traditional discourse in the articles by Vasyl Ivashko, “Mif pro Vasylia Stusa yak dzerkalo shistdesiatnykiv,” Svitovyd, No. 3 (1994): 104–120; Kost Moskalets, “Strasti po Vitchyzni: Lyst do mandrivnyka na Skhid,” in his Liudyna na kryzhyni (Kyiv: Krytyka, 1999), 209–254.

8 See Mykhailo Naienko, “Vystup na pershykh Stusivs’kykh chytanniakh,” Slovo i Chas, No. 6 (1998): 26–28; Dmytro Stus, “Palimpsesty Vasylia Stusa: tvorcha istoriia ta problema tekstu,” in Vasyl Stus, Tvory, Vol. 3, Book 1: 13.

9 Naienko, “Vystup na pershykh Stusivs’kykh chytanniakh”, 28.

10 Vasyl Stus, “Holos z Ukrainy,” in his Tvory, Vol. 4: 482.

11 Idem, “Lyst do druziv vid 30.07.1978,” ibid., 468.

12 Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, “Stusove ‘samosoboiunapovnennia’ (iz rozdumiv nad poeziieiu Vasylia Stusa),” Suchasnist’, No. 6 (1995): 137–144.

13 Yurii Lotman, “Literaturnaia biografiia v istoriko-kul’turnom kontekste,” Uchenye zapiski Tartuskogo universiteta: Trudy po russkoi i slavianskoi filologii, No. 683 (1986): 106.

14 Ivan Dziuba, “Rizbiar vlasnoho dukhu,” in Vasyl Stus, Pid tiaharem khresta: Poezii (Lviv: Kameniar, 1991), 19–20.