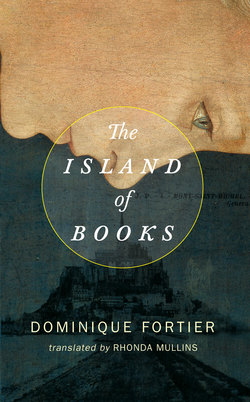

Читать книгу The Island of Books - Dominique Fortier - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe first time I saw it I was thirteen years old, that limbo of an age between childhood and adolescence when you already know who you are but don’t yet know if that’s who you will ever be. It was like love at first sight. I don’t remember anything very specific, aside from a certainty, a wonder so deep it was like a stupor: I had found the place I had always been looking for, without realizing it, without even knowing it existed.

Twenty-five years would pass before I would see it again. When the time came to return, I suggested that we not go: we didn’t have much time before we had to head back to Paris; they were calling for rain; it would probably be crawling with tourists. In truth, I was afraid, the way you’re afraid any time you go back to the places of your childhood, afraid of finding them diminished, which means one of two things: either they appeared larger because your eyes were so small, or along the way you lost the knack for wonder, either of which is a devastating idea. But it hadn’t changed, and neither had I.

§

No matter what angle you look at it from, you can’t see exactly where the rock ends and the church begins. It’s as if the mountain itself is narrowing, stretching, tapering to a point – without human intervention – to give the abbey its shape. It’s as if the rock one morning decided to climb toward the heavens, stopping one thousand years later. But it didn’t always look the way it does today: the familiar silhouette that has been captured in countless photographs, topped by the spire on which the archangel dances, dates only from the nineteenth century.

Before the seventh century, Mont Saint-Michel didn’t even exist; the rocky isle where the abbey stands today was known as Mont Tombe – a mountain twice over, because it seems that the word tombe didn’t mean a tomb or a grave, but a simple knoll.

Around the sixth century, two hermits living on Mont Tombe erected two small chapels, one dedicated to Saint Stephen (the first Christian martyr) and the other to Saint Symphorian (to whom we owe the strange and illuminating phrase, uttered as he was being tortured, The world passes like a shadow). They lived in complete isolation, devoting their days to prayer and their nights to holy visions. They lived with nothing: each one had a cowl, a coat and a blanket, and they had one knife between them. When they were short on food, they would light a fire of wet moss and grass; from the shore, residents would see the smoke and load up a donkey with food, and the beast would travel the island’s road alone to deliver supplies to the holy men, who did not want to sully themselves with human contact. The men would unload the provisions a bit reluctantly; they would have preferred to need only their faith to sustain them. The donkey would return along the same path, empty baskets slapping against its flanks, its step light in the sand of the bay.

Legend, or a variation on the legend, has it that one day the donkey ran into a wolf, which devoured it. From that day on, the wolf brought food to the hermits.

§

During my daughter’s first summer, we would go for a walk every morning. After a few minutes, she would nod off in her stroller, and I would stop at Joyce Park or Pratt Park to watch the ducks. It was a moment of peace, often the only one in the day. I would sit on a bench in the shade of a tree, pull a small Moleskine and a felt pen from the bag on the stroller, and as if in a dream I would follow the man who more than five centuries ago lived among the rocks of Mont Saint-Michel. His story would mix with the squawking of the ducklings, the wind blowing through the two ginkgos, male and female, the squirrels racing through the towering catalpa with leaves broad as faces, and the fluttering eyelids of my daughter, who had surrendered to sleep. I would jot all this down haphazardly on the page because it seemed to me that these moments were important and that unless they were recorded, they would slip from my grasp forever. My notebook was half novel, half field notes, an aide-mémoire.

In the evening, I often didn’t have the energy to bring in the stroller before going to bed. One night, there was a big storm that soaked everything. In the morning, the notebook had doubled in volume and looked like a water-soaked sponge. Its pages were crinkled, and half the words had disappeared – specifically, the middle half: the right half of the left-hand pages and the left half of the right-hand pages. The rest could still be read clearly, but halfway along each line the words became blurred, faded, washed out to the point of disappearing. That may be how, with their ink running together, my story ended up merging with the story of Mont Saint-Michel. I couldn’t unravel them.

This anecdote is a lot like the final scene in On the Proper Use of Stars, in which Lady Jane knocks her cup of tea over the maps she has spent hours drawing, the colours running as she watches. If I had invented it, I would have written it differently. But there you have it, every day words drown in the rain, tears, tea, stories get tangled up, the past and the present come together, the rocks and the trees talk to each other above our heads.

How these 2 men who

never existed but whom I try

To invent at same time

nt where they live

will they do to

reach the shore

Pratt Park

I know they

to write

I dreamed that night that the abbey

was drifting on

a stormy sea, brushing against

riding out waves as high as

§

In the year of our Lord 14**, Mont Saint-Michel towered in the middle of the bay; the abbey stood tall at its centre. In the middle of the abbey, the church was nestled around its choir. A man was lying in the middle of the transept. The heart of this man held a sorrow so deep that the bay wasn’t enough to contain it.

He didn’t have faith, but the church didn’t hold that against him. There is suffering so great that it exempts you from believing. Sprawled on the flagstones, arms spread wide, Éloi was himself a cross.