Читать книгу Taiho-Jutsu - Don Cunningham - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

After publication of my first book, Secret Weapons of Jujutsu, I discovered that my readers shared a wide variety of interests in Japanese culture and history. I received numerous questions, comments, and even additional tidbits of information from hundreds of martial arts practitioners, historical re-enactors, chambara fans, and Japanese sword and armor collectors. Many are genuinely interested in learning about and preserving historical traditions from the Edo period. During our discussions and correspondence, though, I was surprised by how many also seem to share a somewhat distorted view of the people and lifestyles of this era. The samurai is often viewed as a chivalrous knight-errant, strictly adhering to a well-defined code of conduct. If considered much at all, commoners are often viewed as subservient, meekly deferring in their submissiveness to the samurai elite.

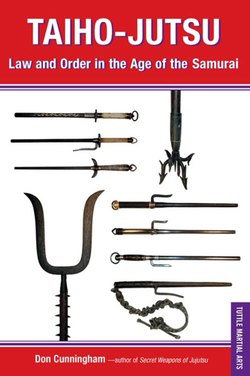

I decided to begin a new book, this time focusing on Edo-period arresting arts and implements and including new information gleaned from my ongoing investigations. I also wanted to discuss many of the social and political influences that impacted all classes of the Japanese feudal society.

About this time, I obtained a copy of the out-of-print book Jutte Torinawa Jiten−Edo Machi Bugy to Taihojutsu. After translating several sections, I realized it contained a wealth of information about jutte and other arresting implements, so I wrote to the author, Nawa Yumio sensei. In short time, he responded and we agreed to meet during a research trip I took to Japan.

Nawa sensei and his students were extremely helpful, demonstrating jutte techniques from Edo Machikata Jutte-jutsu and taking me for a guided tour of his extensive weapons collection then on exhibit at Meiji University Criminology Museum. During our discussions in his apartment, we happened to touch on the subject of matoi, a sort of fireman’s standard often featured in festival parades. A matoi consists of many strips of thick paper or soft cloth and is often mounted on a sasumata, a pole-arm with a U-shaped appendage similar to those used for making arrests. I had heard the matoi was not simply a unit banner but was actually used to help fight fires.

Nawa sensei explained how the Edo-period firemen, recruited from the lowest classes of society, would soak the matoi strips in water, then station themselves on peaks of nearby buildings or even the rooftop of the burning structure. They would then spin the matoi to capture burning embers floating in the wind, thus preventing the flames from spreading. He further explained that the other firemen would also line up on the roof peak, prepared to replace the matoi holder should he succumb to the smoke or heat.

As he described the functions of these feudal-era firemen, I was struck by how their dedication to duty and self-sacrifice paralleled the same traits so vividly demonstrated by the New York City police and firefighters in the aftermath of the recent terrorist attack. Like their Edo-period counterparts, they had bravely rushed into harm’s way to assist the victims, many of them sacrificing their own lives in their valiant efforts.

It was a great analogy for my project. The differences between Japanese and Western cultures are minor when compared with those between our modern world and life during the Edo period under the rule of the Tokugawa shgunate. Yet this simple story about feudal-era firemen demonstrates that we still share many basic human traits, both good and bad. Despite our vast cultural differences, human nature apparently has more in common than not.

Acknowledgments

Many individuals contributed information, assistance, and encouragement for this project. Without their help, this book would not have been realized. I am especially grateful to the following:

• Nawa Yumio, the last ske of Masaki-ry Manrikigusari-jutsu and Edo Machikata Jutte-jutsu and author of numerous books about his research into feudal-era arresting implements and procedures, for sharing his insights and for his contributions to this project. His correspondence has provided a wealth of information and details unavailable from any other source.

• S. Alexander Takeuchi, Department of Sociology at the University of North Alabama, for his detailed critiques of my early drafts and for his contributions to the subject matter. Dr. Takeuchi provided considerable information regarding feudal-era weapons restrictions and his knowledge of Edo-period publications.

• Kusunoki Toshi, president of Bokunan-do, my business associate, my sempai, and my friend, for his support and encouragement, especially in coordinating my visits and help translating during my interviews with Nawa sensei.

• Mizutani Tomonori and his wife, Junko, for demonstrating Masaki-ry Manrikigusari-jutsu, as well as for translating Nawa sensei’s letters and the tour of his extensive arresting implement collection on display at Meiji University Criminology Museum.

• Rich Hashimoto for his fantastic line drawings of taiho-jutsu techniques.

• My fellow senior members of Fox Valley Martial Arts judo club for posing for the illustrations.

• Brian Vermeulen for his enthusiastic support of my efforts, and his wife, Natalie, for information regarding the twitch used in Western horsemanship.

• John Quinn, instructor of Masaki-ry Kusari-jutsu and Edo Machikata Jutte-jutsu, for his advice and comments.

• Yamato Luna, NHK Visual and Audio Archives, for her help in locating photographs of actors and jutte-jutsu from NHK’s television series library.

• The staff at Tokyo National Museum, Meiji University Criminology Museum, Keisatsu Museum, and Fukagawa Edo Museum for their cheerful assistance and hospitality.

• Ashley Benning, editor for Tuttle Publishing, for her invaluable assistance and editorial suggestions.

• And finally, my wife and son, Lynn and Cory, for their belief in me, their patience, and their continued support in all my pursuits. Any errors are mine alone.