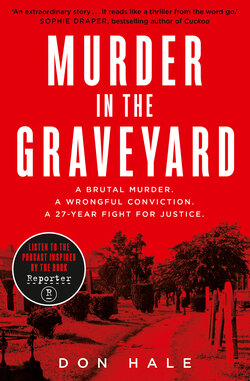

Читать книгу Murder in the Graveyard - Don Hale - Страница 13

YOUTH ON MURDER CHARGE IS FOUND GUILTY

ОглавлениеStephen Downing, aged 17, was found guilty of murdering 32-year-old typist Mrs Wendy Sewell in a cemetery in Bakewell, Derbyshire, by a unanimous verdict.

Downing, who was alleged to have bludgeoned his victim with a pickaxe shaft and sexually assaulted her before leaving the body among the tombstones, was ordered to be detained at the Queen’s pleasure. They took only an hour to reach their unanimous verdict last Friday.

Passing sentence, Mr Justice Nield told Downing, who worked in the cemetery as a gardener, ‘You have been convicted on the clearest evidence of this very serious offence.’

Mr Patrick Bennett QC, prosecuting, had described how Downing had followed Mrs Sewell in the cemetery before carrying out the savage attack with a pickaxe handle. Downing claimed that he had found Mrs Sewell’s half-naked body and then sexually assaulted her.

Mrs Sewell, who lived at Green Farm, Middleton-by-Youlgreave, died in hospital two days after the attack from skull and brain injuries. Downing was alleged to have admitted the assault late at night after spending several hours in the police station. He was alleged to have described how he struck Mrs Sewell with the pick shaft on the back of the head and undressed her.

Police officers denied that Downing had been shaken to keep him awake after spending hours at Bakewell police station. His mother, Mrs Juanita Downing, told the jury that her son had never gone out with girls and only had one good friend.

Downing said that bloodspots on his clothing got there when Mrs Sewell raised herself on the ground and shook her head violently. He had told the jury that he found the victim lying semi-conscious in the graveyard after going home during his lunch hour, but the prosecution said that his lunchtime walk was only an alibi after he had carried out the attack. Downing had pleaded not guilty to the murder.

Other regional papers carried similar copy, stating, ‘A savage assault by a teenager with a pickaxe handle. She sustained repeated blows as many as seven or eight to the head – and had then fallen against tombstones.’

Many papers made a reference to Judge Nield, who kept referring to Downing’s statement, which was ‘signed over and over again’ and formed the main plank of evidence for the prosecution.

To all intents and purposes, it seemed like a fairly straightforward conviction. A confession had been obtained on the day the attack took place, and although Downing retracted it before trial the prosecution case still relied very heavily on this admission.

The trial lasted three days. The jury heard just one day of evidence and took less than an hour to reach their unanimous verdict of guilty. It all seemed so quick, clean and convenient. This alone made me consider it curious and worthy of initial investigation.

* * *

A few days later, I set out on the short but pleasant drive along the A6 to Bakewell. The Downings lived at Stanton View, just a few hundred yards from the cemetery – the scene of the crime. They lived in a small semi-detached house on the council estate. It was the same property that Ray, Juanita, Stephen and his sister Christine had all lived in together until that fateful day in 1973.

Despite the fact that Stephen had remained in custody ever since his arrest, his mother kept his room just as it was. The family had campaigned for his freedom ever since his conviction. Ray never looked well, and at first he probably thought I was just another journalist who would write a brief update and then disappear into oblivion.

Ray told me about his work as a taxi driver and, over a cup of tea, explained how he and Juanita first met in a Blackpool ballroom in 1952, when he was completing his national service in the RAF.

Juanita, who had been watching me like a hawk, told me to call her Nita, and explained how she had been adopted from the age of three and never really knew her parents. Born Juanita Williams, she was brought up near Liverpool. She and Ray later married and moved to Burton Edge in Ray’s home town of Bakewell.

Following national service Ray obtained a job at Cintride, as a first-aid attendant, before he left to drive ambulances and coaches. Stephen was born at their home in March 1956, with their daughter Christine born exactly three years later.

Ray said Stephen had a quiet, reserved nature, just like his mother, and was good with his hands but struggled academically. He confirmed that Stephen had the reading ability of an 11-year-old at the time of the murder, and said he believed himself to be a failure at school, with few friends, and preferred his own company.

Nita, though, explained how Stephen loved animals, and said that on the day of the attack he returned home to change his boots and to feed some baby hedgehogs found abandoned just a few days earlier.

She also said Stephen was a bit lazy and a poor time-keeper – a worrying problem that had cost him several jobs. On the day of the cemetery attack Stephen was employed there as a gardener for Bakewell Urban District Council.

I knew that if I were to have any hope of understanding this case and the Downings’ allegations, I would need to examine the crime scene myself. Ray agreed to give me a tour of the cemetery, and we walked across the road to it. It was hard to imagine how such a gruesome murder could have been committed in broad daylight, and so close to a busy housing estate, with much of the area overlooked by dozens of houses. Ray was somewhat disappointed that I had not read much of his paperwork, and at first seemed quite abrupt. I told him that I needed to keep an open mind.

The cemetery was situated at the top of a steep hill overlooking Bakewell. The main access was via two large iron gates. Just inside was a gatekeeper’s lodge. It was quite a compact area, probably about 450 yards in length, with two main tarmacked pathways running parallel, one adjacent to Catcliff Wood and the other close to a large beech hedge. The woodland area included a dark, secluded section. The main path ran directly towards the old chapel, and a bit further on and to the rear was the unconsecrated chapel, where Stephen worked at the time of the murder.

Ray showed me where Wendy Sewell was attacked. He then indicated where Stephen said he found her, lying on the path next to an old grave. The headstone bore the inscription ‘In the Midst of Life We Are in Death’. It was the grave of Anthony Naylor, who died in 1872.

Immediately behind the grave was a low drystone wall, and a few feet below was Catcliff Wood. I could see how someone could easily escape if they had attacked Wendy, disappearing into thick undergrowth.

As we wandered further along, Ray pointed out another spot across some displaced gravestones, back towards the centre path. ‘Now here is where Wendy moved to,’ he explained.

‘Moved to?’ I asked, as we carefully negotiated our way around a number of ancient and broken graves.

‘Yes. After Stephen found her he went to get help, but when he returned she’d moved,’ he said. Ray then stopped next to the grave of Sarah Bradbury. ‘Wendy was found just here.’

I was surprised. ‘So how did she move, Ray?’ I asked, wondering how a seriously injured woman could drag herself 25 yards or so along the path, and across several gravestones.

‘Well, there’s the mystery,’ said Ray. ‘No one has been able to answer that one. It didn’t come up at trial either, and the police never queried it.’

Ray then showed me Stephen’s former workplace inside the unconsecrated chapel. He explained that this was where the council workers stored their tools, and that it had been used by quite a few men at the time of the murder.

We turned and headed back out towards the main gates, and I tried to put the case into some sort of perspective as I listened to Ray. He kept mentioning the names of several individuals who had supposedly been identified near the cemetery at that time. I realised I would need to read his papers for any of this to make sense.

As we headed part way down the Butts, a very steep walkway heading back into town, Ray showed me the Kissing Gate, an old two-way iron contraption that led back into Catcliff Wood.

It was the reverse route to that taken by the victim as she approached the cemetery during her lunch break. It was also the path taken by a number of key witnesses, who could perhaps have helped confirm Stephen’s alibi and his movements on the day.

As I tried to consider all the probabilities and possibilities offered by Ray, I thought this so-called remote location appeared more like Piccadilly Circus immediately prior to and just after the attack, with people coming and going back to work after lunch. It seemed to be a simple routine, and yet, according to Ray, everyone reported different timings and information within their statements.

We returned to the Downings’ home, where the kettle was already whistling on the stove. Nita had seen us both walking back, and as we walked in she said, ‘I thought you would have been back before now.’

‘There’s a lot to see,’ Ray replied. ‘And Mr Hale wanted to see everything.’

‘It’s Don, Ray. Call me Don. This Mr Hale sounds more like a bailiff.’

Ray laughed. ‘Don’t mention bailiffs. There’s one round here that we don’t care for at all, isn’t that right, Nita?’

She laughed too. It was obviously some in-joke. Nita handed me a hot mug of tea. It was a family home full of personal mementoes and treasured photographs, yet Stephen’s face was always missing, apart from a few childhood snaps. Their only contact with him now was on infrequent visits to a distant prison several hours’ drive away.

This thought of Stephen suddenly reminded Ray of something, and he scurried away into the lounge before returning with a large basket. He said excitedly, ‘This is Stephen’s clothing from the day of the attack,’ and tipped out the contents on to the table.

I was shocked to see Stephen’s old jeans, T-shirt and work boots, together with rings, a watch and a leather wrist strap.

I couldn’t understand why the police had returned these items, and why the family still retained his clothes after all these years. Incredibly, as I looked much closer, I could just about see some very tiny spots of blood on his T-shirt, but only because they were highlighted by a yellow forensic marker.

Ray pointed out a particular dark stain on the left knee of these discoloured and dirty jeans, which he said was congealed blood. No other stains were obvious to the naked eye. ‘Look at all these clothes,’ he said. ‘They are not drenched in blood. And yet our Stephen was said to have battered this poor woman to death.

‘If he had, he would have been covered in blood from head to toe. The only blood he got on his clothes was from kneeling next to her when he found her. What’s more, I know the ambulanceman who took Wendy to hospital that day. He carried her into the ambulance.

‘He said he was covered in blood, as she was bleeding so much. He had to burn all his clothes afterwards, they were completely ruined. They were absolutely soaked in blood. You can talk to him. His name is Clyde Bateman. I used to work with him at Bakewell ambulance station. I was a senior ambulance driver and he was my boss.

‘He was summoned to attend an appeal eight months after the trial but was never called as a witness. He wanted to talk about the bloodstaining. He’s now retired, but every time I see him he maintains that Stephen didn’t have enough bloodstaining on him to have committed the attack.’

Ray was still excited. He was sweating and slightly breathless. He eventually paused as I queried, ‘How come you have Stephen’s clothes?’

‘They told me to take him down a change of clothes to the police station, and then they sent these off for testing. They gave us back the watch and the jewellery on the same night as the attack,’ Ray said.

‘The clothes came back later. It’s obvious there’s not enough blood on them, though.’

It was beginning to get dark and, as I had now spent several hours with the Downings, I decided to make a move, but Ray motioned me to sit back down. ‘I’ve a lot more to show you. I’ve got more files and notes. You’ll need to see them all,’ he pleaded.

I had to take an urgent step back. It had been quite an afternoon. The Downing family had made this a personal crusade for the past 20-odd years, but I didn’t want to be drawn in or build up their hopes before I got my bearings.

I politely declined Ray’s offer. I told the pair I had to get back to work. I wanted to spend some time going through the files so that I could examine their claims in more detail. I decided I would make an early start the next day, and cancelled my weekend engagements.

For a split second I felt complete panic. Ray’s papers were piled high next to my desk, and I wondered, What if the cleaner has arrived early and dumped them, not realising their importance?

When I returned to the office, the pile was thankfully still intact. I phoned Ray to arrange another meeting. He suggested I should go the day after next, as Stephen was due to ring from prison. He thought it would be good to speak to him directly.

By then everyone else had left the office. I had my coat on ready to follow them, my hand on the door handle to leave, when suddenly the phone rang. After such a busy day I was in two minds whether to answer it, but I reluctantly picked up in the end.

‘Good evening, Matlock Mercury. Don Hale. Can I help you?’

There was complete silence.

I asked again, ‘Hello, hello? Matlock Mercury.’ Still silence, although I had the impression someone was listening at the other end. I thought I could hear someone breathing, and a slight background noise.

Then a mature man’s husky voice shouted angrily, ‘Keep your fucking nose out of the Downing case if you know what’s good for you! Do you get my meaning?’

Before I had the chance to answer, he slammed down the phone.