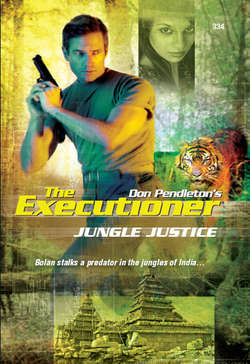

Читать книгу Jungle Justice - Don Pendleton - Страница 11

3

ОглавлениеFort McHenry, Baltimore

It had been Bolan’s turn to choose the meeting place, and he’d made his selection on a whim. It had to be within an hour’s drive of Washington, but within those parameters anything went.

He’d chosen Fort McHenry for its history— “Star Spangled Banner,” and all that—as well as its proximity to certain high-crime streets that might prove useful if the call from Hal Brognola concerned another job.

And what else would it be?

Granted, Brognola was a friend of long standing who phoned his regards on holidays, birthdays and such. He couldn’t send cards, because Mack Bolan had no fixed address. But a weekday phone call requesting a face-to-face ASAP could only mean work.

And work meant death, no matter how they tried to dress it up in frills.

The fort had been restored with loving care. Tourists could stroll along the parapets where early defenders had cringed from the rocket’s red glare, clutching muskets and sabers, most praying they wouldn’t be called on to use them.

That had been during the country’s second war with Britain, going on two hundred years ago, and Bolan’s homeland still hadn’t achieved a lasting peace. Its history was scarred by conflict stretching from the shot heard ’round the world to Kabul and Baghdad. The freedoms cherished there were sacrosanct to Bolan, but their price was high.

He wondered, sometimes, what the politicians thought they had achieved, besides securing their own reelection, but it never troubled him for long. The republic had survived good presidents and bad, congressmen who helped the poor and robbed them blind, judges who did their level best and others who were on the take from every scumbag they could find. America endured, sometimes despite its leaders, rather than because of them.

In Bolan’s world it was a different story. He’d quit taking orders when he shed his Army uniform and launched a new war of his own, against the syndicated criminals responsible for nearly wiping out his family. That war had taught him things he’d never learned in Special Forces training, and Bolan had taken those lessons to heart.

These days, he was unique among all other warriors he had ever known or studied. The nearest facsimile came from ancient Japan, when masterless samurai called ronin traveled at will through a feudal landscape, choosing their battles and renting their swords to the highest bidder.

Bolan wasn’t a mercenary, though. He’d cast his lot with Hal Brognola at the Department of Justice, and Brognola’s covert-action teams at Stony Man Farm, in the wild Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. But he didn’t belong to them. Bolan was free to turn down any job that didn’t suit him, though he rarely exercised that privilege. In most cases he found that Brognola’s concern, his sense of urgency, matched Bolan’s own.

That didn’t mean he’d want the job the big Fed brought to him this morning, at Fort McHenry. Every time they met, a part of Bolan’s mind was ready to decline the mission, picking it apart in search of elements that made it hopeless or unworthy of his time. It was a rare day when he found those elements—not half a dozen times in all the years he’d worked with Hal—but it could happen.

As his compact with Brognola left him free to pick and choose, so it allowed Bolan to chart selected missions of his own, without Brognola’s go-ahead. Brognola nearly always backed him to the limit, but they both knew that it wasn’t guaranteed, and if the man from Washington said no, it wouldn’t be a deal breaker for either of them.

Not yet, anyway.

Moving among the tourists, eavesdropping on fragmentary conversations, Bolan marveled at their ignorance of history. One woman thought Fort McHenry had been shelled by “Communists” during the Civil War. Her male companion solemnly corrected her, insisting the aggressors had been French. Most of the others didn’t seem to care what might’ve happened there, so long ago, as long as they could spend a morning in the sunshine, briefly free from care.

And maybe that, thought Bolan, was the reason many of his nation’s battles had been fought.

History books extolled the U.S. combat soldier’s dedication to abstractions—Justice, Freedom and Democracy were those most prominently listed. Bolan, for his part, had never met a soldier who spent any barracks time at all debating politics, when there was talk of women, sports or food to be enjoyed. And in the orchestrated panic that was battle, he had never heard a fighting man of either side die with a patriotic slogan on his lips. They asked for wives or lovers, parents, siblings—anyone at all, in fact, except the leaders who had put them on the battlefield.

Armies defended or invaded nations. Soldiers fought to stay alive and help their buddies. Only “statesmen” waged war for ideals, and most of them had never fired a shot in anger, or been fired on in return.

Bolan had once maintained a journal, filled with thoughts about his private wars, the Universe, his place within the scheme of things and mankind’s destiny. He’d discontinued it some years ago, more from a lack of idle time than any shift in feeling, and he didn’t miss it now.

Who’d ever read or care about his private thoughts, in any case? Officially, he was a dead man, had been since his pyrotechnic finish had been staged by Hal Brognola in NewYork. From there, he’d been reborn—new face, new life, new war.

Except, in truth, his war had never really changed.

His enemies were predators in human form, who victimized the weak and relatively innocent. Like some unworthy patriots and holy men, they dressed their crimes in disguises of infinite variety. They were left- and right-wing, conservative and liberal, Muslim and Christian, Jew and gentile, male and female, young and old. They came in every color of the human rainbow, but they always wanted the same thing.

Whatever they could steal.

Bolan stood in their way, sometimes alone, sometimes with comrades who were dedicated to the fight for its own sake. And while he knew he couldn’t win them all, he’d done all right so far.

He found the spot he’d designated for his meeting with Brognola, leaned against the rough stone of the parapet and settled in to wait. The man from Justice thrived on punctuality, but Bolan was ten minutes early. He had time to kill.

He couldn’t see or hear the ghosts who walked those grounds, but Bolan never doubted they were present, bound by pain and sacrifice to the last battleground they’d known in life. And something told him that they didn’t really mind.

BROGNOLA STEPPED UP to the wall at Bolan’s side, and said “Been waiting long?”

“Not too long,” Bolan answered. “Shall we walk?”

“Suits me,” Brognola said.

He studied Bolan, as he always did, striving for subtlety. It wasn’t good to stare, but he supposed that shooting furtive glances from the corner of his eye would make him seem ridiculous, like something from a Peter Sellers comedy.

“How are you?” he inquired at last.

“Getting along,” Bolan replied.

Okay. No small talk, then.

“I’ve got a project that I thought might suit you, if you’re interested,” Brognola told him, cutting to the chase.

“Let’s hear it.”

“What do you know about India?”

Bolan considered it, then said, “Huge population. Sacred cows. Border disputes with Pakistan and China. Trouble with the Sikhs.”

“Endangered species?” he suggested, prodding.

Bolan shrugged. “I wouldn’t be surprised.”

“What about tigers?”

“Big and dangerous. Just ask Siegfried and Roy.”

“I’m thinking more of tigers in the wild.”

“Not many left, if memory serves,” Bolan said.

“They’re making a comeback of sorts on Indian game preserves,” Brognola told him, “but there’s still a thriving trade in pelts and organs.”

“Organs?”

“Right. Go figure. In the Eastern culture, certain organs are believed to help male potency.”

“I thought that was rhinoceros horn,” Bolan said.

“Same thing,” Brognola admitted. “Different strokes for different folks.”

“So, poachers,” Bolan said.

“Big-time. Not only tigers, but elephants, too. Apparently, it’s a major crime wave.”

“Too bad,” the Executioner replied. “But still—”

“I know, it’s not our usual.”

“Not even close.”

“Does the name Balahadra Naraka ring any bells?” Brognola asked.

“Vaguely. Can’t place it, though.”

“He’s a legend of sorts from what I gather,” the big Fed explained. “Started out as a small-time poacher, then he caught a prison sentence and escaped, killing some guards as he went. That was ten or twelve years ago, and the government’s been hunting him ever since. He’s the Indian equivalent of Jesse James or John Dillinger. Naraka has a gang, hooked up with dealers in Calcutta and buyers all over the world. Reports vary, but it seems he’s killed at least a hundred game wardens and soldiers. Some reports claim two hundred or more.”

“Bad news,” Bolan said, “but I still don’t see—”

“Our angle?” Brognola had anticipated him. “Last week a U.S. diplomat, one Phillip Langley, paid a visit to West Bengal with his wife. Langley is—or was—a member of the President’s task force on preservation of endangered species, working in conjunction with the United Nations.”

“Was a member?” Bolan asked.

“He’s dead,” Brognola replied. “The wife, too. Some of Naraka’s people jumped their convoy on a game preserve ninety miles outside Calcutta. Killed their escorts on the spot, then snatched the Langleys and demanded ransom.”

“Washington, of course, refused to pay,” Bolan said.

“Right. So, anyway, the army got a lead on where Naraka had them stashed and tried to pull a rescue. When the smoke cleared, they had two dead hostages and one small-timer from the gang, but no sign of Naraka and the rest.”

“Which leaves the White House angry and embarrassed,” Bolan guessed.

“And shit still rolls downhill,” Brognola said. “This load just landed on my doorstep yesterday.”

“You want Naraka chastised.”

“Neutralized,” Brognola said, correcting him. “Along with anybody else who had a hand in murdering the Langleys.”

“And the local government can’t handle it?”

“They’ve spent more than a decade chasing him around in circles, getting nowhere. As I mentioned, he’s already killed at least a hundred of their officers, and still they haven’t laid a glove on him. No reason to suppose they’ll score a sudden breakthrough, just because he smoked a couple of Americans.”

“A diplomatic squeeze might do the trick,” Bolan suggested.

“Some say we’re spread too thin as it is, or throwing too much weight around already. Either way, the word’s come down to handle it outside normal channels.”

“Ah. And where would I start looking if the natives don’t know where to find their man?”

“I said they haven’t found him,” Brognola replied. “That doesn’t mean they don’t know where he is.”

“Collusion?”

“Or ineptitude. It wouldn’t be the first time, right?”

“Unfortunately, no,” Bolan agreed. “My question’s still the same. Where would I start?”

“Calcutta,” Brognola suggested. “It’s the capital of West Bengal, Naraka’s happy hunting ground, and anything he moves to foreign buyers will be passing through the city. I’ve already tapped the Company for contacts, and they’ve got a man on standby to assist you if you take the job.”

“A native?”

“Born and bred,” Brognola said. “He’s on the books with a ‘reliable’ notation.”

“Name?”

“I’ve got his file here,” Brognola said, raising his left hand to stroke his overcoat, feeling the fat manila envelope that filled his inside pocket. “And I brought along Naraka’s, with some background on the area.”

“So, is the White House miffed, or is there some real likelihood this character may pose a future threat?” Bolan asked.

“To the States?” Brognola shrugged. “Who knows? It’s not his first kidnapping, just the first involving U.S. citizens. Our analysts are split fifty-fifty, as to whether the experience will scare him off or piss him off so badly that he wants another piece of Uncle Sam.”

“It’s a distraction from his trade,” Bolan remarked.

“Which means he may start taking other risks, making mistakes. I’d hate to see him fixate on the embassy, its personnel. This guy’s been living like a hermit in the jungle since his prison break. I’m not sure he was civilized before that all went down, but he’s a Grade A wild man now.”

“A wild man with a taste for ivory and tigers,” Bolan said.

“And hostages. Let’s not forget.”

“How solid is his dossier?”

“Good question. The ambassador to India says we got everything they have in New Delhi. Beyond that, who knows?”

“Naraka could have someone running interference for him in the government,” Bolan suggested.

“It’s a possibility, all right.”

“And if I find someone like that? What, then?”

“Officially, we’d want to know about it. Off the record, use your own best judgment.”

“All right,” the warrior said, at last. “Let’s see the files.”

THE FILES HAD BEEN condensed, photos and all printed on flimsy paper for convenience and easy disposal when Bolan had finished his reading. He sat on a bench in the sunshine, outside Fort McHenry, with Brognola at his side, watching any stray tourist who wandered too close. Bolan read steadily, absorbing all the salient facts and asking questions when he needed to.

His contact, Abhaya Takeri, was a twenty-six-year-old ex-soldier who had dabbled in private security before landing a dull office job in Calcutta. That had lasted for nearly a year before he got restless, picking up covert assignments from his government, and later from the CIA. It wasn’t clear in Takeri’s case if one hand knew what the other was doing, but he’d managed to avoid any conflicts so far, after three years of service, and that said something for his tradecraft at the very least.

Takeri’s photos were a study in contrast. The first, a posed shot in his army uniform, revealed a stern young man who wouldn’t smile to save his life, proud of his threads and attitude. The other was a candid shot, taken just as Takeri left a small sidewalk café, his arm around a pretty, laughing young woman. Takeri’s smile seemed genuine, good-humored, as if he enjoyed his life. The flimsy printouts meant that Bolan couldn’t check the flip side of the photographs for dates, but he assumed the army photo had been taken first. Takeri seemed a little older in the second, definitely more at ease.

Takeri’s record in the military had been unremarkable, and most of what he’d done since entering the cloak-and-dagger world was classified. Of course the CIA didn’t mind leaking what he’d done for India, as long as it had no impact on his work for the Company. Apparently, Takeri had been used to infiltrate a labor union thought to be involved in sabotage—they weren’t, according to his last report—and to disrupt a group of Sikhs who showed displeasure with the government by blowing up department stores. Four bombers had been sent to prison in that case, while their ringleader had committed suicide.

It sounded like a good day’s work.

Takeri spoke three languages, had studied martial arts before and after military service, and he’d qualified with standard small arms in the army.

“Sounds all right,” Bolan said, handing the dossier to Brognola.

Balahadra Naraka was something else entirely. Thirty-eight years old and a career criminal by anyone’s definition, he had survived Calcutta as an orphan, living by theft and his wits on the streets, then fell in with poachers when he was a teenager. The shift to country living didn’t help. Naraka was suspected of killing his first game warden at age nineteen, but no charges were filed in that case and he’d remained at large for three more years, then took a fall for shooting tigers. The charge carried a five-year prison sentence, and he’d spent nearly a year in jail prior to trial. Upon conviction, Naraka had received the maximum and was packed off to serve his time.

It took him nearly three years to escape, but he made up for the delay in grisly style. Using a homemade shank, he gutted one guard on the cell block, took another hostage and escaped in one of the prison vehicles. Car and hostage were abandoned on the outskirts of civilization, the guard decapitated, with his head mounted as a hood ornament.

Since then, for nearly twelve years, Balahadra Naraka had been a hunted fugitive, although it barely showed from his lifestyle. Granted, he spent most of his time in tents or tiny jungle villages, but so did half the population of West Bengal. His photos—half a dozen snapped by Naraka’s own men and sent to major newspapers—always depicted him in a defiant pose, armed to the teeth, standing beside the carcasses of tigers, elephants, or men in uniform.

Brognola had been right about the bandit-poacher’s body count. Although it seemed most of his victims were officials—cops, soldiers, game wardens—no two sources ever quite agreed on how many men he’d killed. The lowest figure Bolan saw, in excerpts from assorted press clippings, was 105; the highest, lifted from a sensational tabloid, ascribed “nearly four hundred” slayings to Naraka and his gang.

It was peculiar, Bolan thought, that no official source kept track of government employees murdered by a bandit on the prowl, but numbers didn’t really matter in the last analysis. Naraka was a dangerous opponent, and he’d moved from killing local lawmen to murdering U.S. diplomats.

Bolan assumed the Langley snatch had been a one-time thing, impulsive, maybe even carried out by a subordinate without Naraka’s prior knowledge. It made no difference, though, because Naraka had a lifelong pattern of internalizing and repeating bad behavior. If he’d been apprehended for his first known homicide, it might’ve made a difference. But as it was…

Naraka might be something of a folk hero to rural villagers, who welcomed charity and anyone who helped remove the threat of tigers from their dreary lives, but he still qualified as a mass murderer—perhaps the worst in India since British troops suppressed the thugee cult during the nineteenth century. If Bolan could supply the final chapter to Naraka’s long and cruel career, so much the better.

“He’s a tough one,” Bolan told Brognola. “Knows the ground like Jungle Jim. It won’t be easy to find him, and even then—”

“You’ve tackled worse,” Brognola said.

“Maybe.” Bolan handed back Naraka’s file. “Just let me check the ground.”

It was the worst of both worlds—first, a teeming city, second largest in the country, steeped in grinding poverty, then swamps and jungles rivaling the thickest, least hospitable on Earth. The Sundarbans, where Bolan would be forced to hunt Naraka if he couldn’t catch his target in Calcutta, spanned 2,560 square miles in West Bengal, with more sprawling across the border into Bangladesh. The Indian portion included a 1,550-square-mile game preserve, where three hundred tigers were protected by law, since the early 1970s.

Nor did the Sundarbans consist of any ordinary jungle. Seventy percent of the region lay under salt water, comprising the world’s largest mangrove swamp, crisscrossed by hundreds of creeks and tributaries feeding three large rivers—the Brahmaputra, the Ganges and the Meghna. Access to much of the region was boats only, and if tigers missed a visitor on land, the tourist still had to watch out for sharks and salt-water crocodiles. Electrified dummies had failed to discourage the cats, and every tourist party that entered the Sundarbans traveled with armed guards.

All that, before poachers and bandits were added to the mix.

“Sounds like malaria country,” Bolan said.

“I’ve got a medic on standby to update your shots,” Brognola answered.

“Thoughtful to a fault.”

“That’s me.”

“All right,” the Executioner replied. “I’m in.”