Читать книгу Enemy Agents - Don Pendleton - Страница 10

2

ОглавлениеWashington, D.C.

Four days earlier, Bolan had strolled through crowds of tourists on the National Mall, making his casual way toward the pale upraised finger of the Washington Monument. His destination lay adjacent to that obelisk, on 1.9 acres of land allotted by Congress in the 1980s, on Fifteenth Street, renamed Raoul Wallenberg Place.

Bolan knew the name from history. Raoul Wallenberg had been a Swedish diplomat stationed in Budapest during the German occupation of 1944–45. He had issued protective passports to Hungarian Jews, saving tens of thousands from slaughter—and then, ironically, was jailed when Soviet troops “liberated” the country from Nazi rule. Dying under questionable circumstances at Moscow’s Lubyanka prison in 1947, Wallenberg had been honored worldwide once his story was told.

It was only fitting that his name now marked the street outside of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Bolan entered the museum, collected his free pass from a clerk in the Hall of Witness and proceeded to the first-floor elevator. Self-guided tours were timed, leaving Bolan five minutes to wait in the lobby, and start on the fourth floor, with visitors working their way back down to street level through various halls and exhibits.

Bolan surveyed the first of four permanent exhibitions. This one depicted the Nazi assault on German Jews from 1933 until the 1939 invasion of Poland, including documents, photographs and other relics of the years that included the Reichstag fire and Kristallnacht riots. Lower floors, he knew, presented the rest of a grim history in chronological order: the “Final Solution” on Three, and the nightmare’s “Last Chapter” on Two. Altogether, the museum contained nearly thirteen thousand artifacts, eighty thousand photos, one thousand hours of archival film footage, nine thousand oral histories, and some forty-nine million documents charting the course of brutal genocide.

Tragically, it hadn’t been the last.

Man’s inhumanity to other humans was the world’s oldest story, played out in grim new headlines every day.

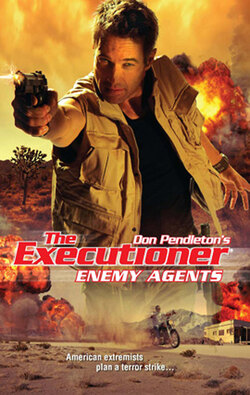

Which kept the Executioner busy year-round.

On this bright spring morning, he was killing time indoors, studying bleak reminders of how cruel humankind could be, while waiting for his oldest living friend. Their conversation, subject still unknown to Bolan, would inevitably launch him on another journey to the dark side, where he would find predators aplenty still alive and well, working around the clock to victimize the innocent and not-so-innocent alike.

In short, business as usual.

Scanning the photographs of Adolf Hitler and his inner circle, studying their smug and ghoulish faces, Bolan wondered if someone like himself could have derailed that tragedy, if sent to solve the problem soon enough. Would half a dozen well-placed bullets have changed anything at all?

Or was the tide of history inevitably tinged with blood?

Bolan’s experience had taught him not to second-guess the vagaries of human nature. Every personality contained a blend of traits, defined as “good” or “bad” by different societies. Some cultures valued warlike attitudes, while others favored meekness and pacivity. Some cultivated stoicism and endurance in the face of suffering, while others honored conscientious suicide.

But every nation, race and culture recognized that some people could only be restrained by force. If left at large, to exercise their will, the predators wreaked havoc.

Sometimes, they wound up in charge.

Bolan harbored no illusions about saving the world. He wasn’t a statesman, diplomat or philosopher. He couldn’t sway the masses with a glib turn of phrase and persuade them to trade in their weapons for schoolbooks or farm implements.

Bolan was a soldier, had been since he’d snagged his high-school diploma en route to the Army recruiting depot, breezing through basic training and moving on to Special Forces training at Fort Benning. And there’d been no looking back from there, until his family at home met a fatal snag that pulled him out of uniform and forced him to pursue a different, more personal kind of war.

That phase of Bolan’s life lay far behind him now. In terms of serving with official sanction, he’d been back on track since the creation of Stony Man Farm. In terms of serving fellow human beings, he had never stopped.

Each blow he struck against the predators saved lives that otherwise would have been diverted into dark and deadly avenues. For the enduring benefit of strangers, Bolan walked those alleyways and jungle trails alone.

They felt like home.

As he moved slowly past the Holocaust exhibits, Bolan wondered how it had to feel to be persecuted for a trait you hadn’t chosen and could never change. An accident of birth, say, that determined pigmentation, hair texture, the shape of eyes or nose.

Bolan knew all about the sense of being hunted, but he’d always brought it on himself, by standing in the way of people who would never stop harassing, robbing, killing others until they, themselves, were stopped dead in their tracks. He stopped them, and when their associates came looking for revenge, he buried them.

How long could it go on?

Bolan had no idea and didn’t let the question trouble him.

Turning from blown-up photographs of Nazi signs and posters that he couldn’t read, but which he understood too well, Bolan saw Hal Brognola moving toward him, past a group of children following their teacher through the gallery. Small faces sad and humbled, learning more than they might care to know about their species.

Bolan went to meet his friend.

“NO PROBLEM PARKING?” Brognola asked, as he clutched Bolan’s hand, pumped twice and let it go.

“The walk was nice,” Bolan replied.

“Sorry you had to come in naked,” Brognola went on. “Security’s been tighter since the shooting.”

“Sometimes the hardware weighs me down,” Bolan said.

Back in June 2009, an octogenarian neo-Nazi ex-convict had carried a .22-caliber rifle into the museum, killed a security guard, then fell under fire while trying to shoot other guards. The gunner had survived and was sitting in jail while his case wound its way through the courts at glacial speed. Attorneys at Justice had a pool going, on whether a jury or Father Time would deal with the creep in the cage.

Brognola, for his part, couldn’t care less. As long as the neo-Nazi was off the streets for good, it suited him.

One down. And how many tens of thousands to go?

God only knew.

Strolling past photo displays of the Kristallnacht riots—dazed victims and grinning, moronic attackers—Brognola got to the point. “I assume you keep up with what’s going on in the militia movement?” he asked.

“Yeah, things have really changed since the sixties and the Minutemen,” Bolan replied. “They organized to save America from Red invaders who never showed up, then started robbing banks to stay afloat and ran out of steam when the brass went to prison. Same thing in the nineties, responding to government action at Ruby Ridge and Waco. Last I heard, they’d done a fade around the turn of the millennium. Arrests and memberships way down, since Y2K fell flat.”

“Way down until the last election,” Brognola corrected him. “As it turns out, there’s one thing that riles the far right more than Communists, Jews and the New World Order all thrown together.”

“Should I guess?” Bolan inquired.

“No need,” Brognola answered. “It’s an African-American in the White House, talking peace and universal health care. Turns out ‘Change We Can Believe In’ translates on the fringe to ‘Grab your guns and go to war’?”

“Same old RAHOWA crap?” Bolan asked.

Brognola was painfully familiar with the acronymy. It stood for Racial Holy War, a slogan coined by a white-supremacist “church,” currently used throughout the racist underground by skinheads, brownshirts, Ku Klux Klanners, and some more supposedly “respectable” types who donned Brooks Brothers suits to peddle their message of hatred. Brognola had seen RAHOWA painted on walls, scrawled at crime scenes, and tattooed on flesh—but he still didn’t know how the fantasy sold to anyone with an IQ above room temperature.

“It’s that, and then some,” the big Fed told Bolan. “There’s been talk of white-power nuts plotting to kill the President since he was elected to the Senate, but they stepped up during the White House campaign. The Bureau nabbed four crackpots with a carload of guns at the Democratic Convention. Then, a week before election day, ATF busted a couple of nuts in Tennessee who had the Man at the top of their hit list, with eighty-eight victims in all.”

“Eighty-eight,” Bolan said, shaking shook his head.

“Nothing new under the Nazi sun,” Brognola replied.

H was the alphabet’s eighth letter. Eighty-eight, then, stood for HH—or Heil Hitler to fascists.

“I guess it never goes away,” Bolan said.

“Nope. Keeps getting worse,” Brognola told him. “In September of 2009, someone posted a poll on a social network asking Net geeks if the President should be killed. They took it down pronto, when G-men came calling, but the overnight stats might surprise you. Sometimes I think…aw, hell, never mind.”

He’d been about to say, “The country has gone crazy,” but Brognola knew that wasn’t true. If forced to guess, he would’ve said America harbored roughly the same percentage of bigots as ever, but economic hard times and the fear that money troubles spawned had a potential to inflate the ranks of the lunatic fringe.

“So, long story short?” Bolan prodded.

“Long grim story short, the militias are back,” Brognola said. “They’re growing again, feeding off of the tax protest movement, beating the drum over illegal immigration, and playing more race cards than last time around. You’ve likely heard some of it. ‘The President’s a Muslim,’ ‘he’s not a U.S. citizen,’ whatever crap their tiny brains can generate. It says something about the current atmosphere that millions take at least part of the nonsense seriously.”

“Not much I can do about it,” Bolan said. “You’ve got free speech and freedom of the press, implying freedom to believe some idiotic things. Last time I checked, there was still a Flat Earth Society, and people claiming we never set foot on the moon.”

“Agreed. But none of them intend to kill the President of the United States or spark a civil war.”

“You have someone specific in mind,” Bolan said, “or we wouldn’t be here.”

“It’s like you know me,” the big Fed responded with a weary smile.

Bolan matched the smile and said, “I’m getting there.”

“Okay,” Brognola said. “Clay Halsey. He runs an outfit he calls the New Minuteman Militia out of Southern California. I’ve got the details for you on a CD-ROM. Bottom line, he’s running guns to other fringe groups in the States, and he has ties with neo-fascist groups in Europe.”

“They need guns from us?” Bolan sounded skeptical.

“Call it a mutual admiration society,” Brognola replied. “They’ve been playing the Nazi gig longer than our homegrown crazies. During the Great Depression, you may recall they seized a couple of governments. Final solutions ensued.”

“I know it’s cliché,” Bolan said, “but most people would tell you that can’t happen here.”

“Let’s grant that for the sake of argument. Do we sit back and let them try? Can we afford another murdered president? Another Oklahoma City? God forbid, a homegrown 9/11?”

“If you’ve got the evidence—”

“We don’t,” Brognola interrupted Bolan. “I’m told ATF had someone close to Halsey. An informant, not an agent. Anyway, he dropped some juicy hints and then went MIA. Off-roaders found what the coyotes left of him in the Mojave Desert.”

Bolan frowned. “So, if at first you don’t succeed…”

“Again, it’s like you know me.”

“You want something on this guy before we drop the hammer.”

“I need something on him,” Brognola replied. “To justify whatever happens for the guys upstairs.”

“Well, then,” Bolan replied, “I guess I’d better have a look at that CD.”

BOLAN TOOK THE CD to an internet café in Georgetown, found a carrel in a corner where no one could peer over his shoulder and used an earpiece for the sound track. The first file was titled Background. Bolan opened it and found himself embarking on a history lesson about “militia” subversion.

April 19, 1995, had been the wake-up call, with 168 dead and nearly 700 wounded in the blast that destroyed Oklahoma City’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building and 324 other structures within a 16-block radius. Since then, Bolan learned, various law-enforcement agencies had interrupted or prosecuted at least 75 right-wing terrorist conspiracies across America, from coast to coast and border to border.

The incidents read like a roster of delusional insanity.

Saboteurs calling themselves the Sons of Gestapo derail a train in Arizona, killing one passenger and injuring dozens more. A massive homemade bomb turns up at Reno’s IRS office, defused with minutes to spare. A so-called Aryan Republican Army robs twenty-two banks, then starts killing its own membership. Lone-wolf gunmen strike repeatedly—at schools, churches and synagogues, the Holocaust Museum and a Jewish day-care center in Los Angeles. G-men arrest Klan members on the eve of their attempt to bomb a Texas natural gas refinery, risking the lives of thirty thousand local residents. A “pro-life” terrorist shoots doctors and mails alleged anthrax to dozens of women’s clinics.

The dreadful list went on and on, accompanied by grim-faced mug shots that revealed no hint of common decency, much less remorse. The terrorists who spoke to law enforcement inevitably cast their crimes in terms of patriotic zeal.

We’re taking back our country.

America for real Americans—the ones who look and think and pray like us.

Bolan grew weary of it, closed that file and opened the one titled NMM. As he’d anticipated, it contained a detailed rundown on the New Minuteman Militia, Clay Bertram Halsey commander in chief.

The soldier started with Halsey’s personal dossier, surprised to learn that the man held a doctorate in biochemistry and had taught his subject at a smallish California college until the early nineties, when he’d left the classroom in favor of zany far-right politics. There was no trigger incident on record, nothing to explain the break with academia and sanity. Halsey had drifted through various groups of that era, including a couple with racist leanings, but had reached the twenty-first century without compiling a rap sheet.

As for suspicion, his name had been linked to arms deals, civilian border-watch campaigns in the Southwest, and to a shipment of neo-Nazi pamphlets printed in the States that found their way to Germany, where the recipients were jailed under that nation’s postwar laws proscribing hate speech and denial of the Holocaust. No such statutes existed in the States, so he was free and clear.

Almost.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Firearms, Tobacco and Explosives—still ATF for short, despite the late addition to its title when it joined the Department of Homeland Security in 2002—had been watching when Halsey founded his New Minuteman Militia in 2008. The group had started small, expanding to an estimated fifteen hundred members concentrated in Southern California, with outposts in Arizona and Nevada.

Headquarters for the NMM was located near Victorville, on the western edge of the same Mojave Desert where the ATF’s informant had been left to feed the wasteland’s scavengers. According to the file Brognola had provided, the militia’s turn-coat had been Joseph Allen Gittes, twenty-six, a marginally employed auto mechanic who’d pulled himself back from the brink of methamphetamine addiction while serving time in state prison, then found Jesus, right-wing politics and the patriot militia movement in no particular order.

It was standard stuff, as Bolan understood extremist groups of both Right and Left. Damaged and disaffected individuals were drawn to militant cliques like iron filings to a magnet trawled through dirt. Some claimed to find new meaning for their lives in radical theory. Others simply tried to exorcise their private demons by attacking others—be the targets ethnic minorities, “traitors,” the System, or “The Man.”

Something, somewhere along the line, apparently had driven Gittes to betray his newfound friends of the NMM. He’d been a walk-in at the ATF’s San Diego field office, where agents initially suspected him of clumsily attempting to spy on them on Halsey’s benefit. In time, though, Gittes had produced leads that resulted in the seizure of two midsize arms shipments, taking a few hundred assault rifles and other hardware off the overloaded streets. Agents had listened more attentively when he began to speak of “something big” in the works.

And then, he’d vanished, lost forever.

The autopsy report on Gittes indicated that his legs were broken, blunt force trauma, leaving him alive to crawl across the vast Mojave, seeking help. The desert sun had baked him, dehydrated him, before a snakebite finished off the job. By that time, it was likely a relief.

Agents had questioned Halsey, who professed dismay and grief in equal measure, claiming that he’d missed Gittes around militia headquarters but had concluded—with regret, of course—that the young man had relapsed into tweaking meth and left the movement for another shot at living on the pipe. A feasible suggestion, but it didn’t track with what the dead man’s handlers had observed.

Which left the ATF nowhere. Ditto the FBI, the state police, San Bernardino County’s sheriff, and the other agencies that had examined scattered pieces of the new militia puzzle. Brognola and Stony Man Farm were poised to move against the NMM, but first they needed something to substantiate the “something big” that Halsey was supposed to be preparing.

Taking back our country.

Which meant taking it away from the majority of rational Americans, turning it into…what?

It struck Bolan as a bad idea.

AND SO THE EXECUTIONER prepared for war. He wasn’t rushing into anything, though time was of the essence. That was true whenever Brognola approached him with a new assignment, always an emergency, but rushing blindly into battle wasn’t Bolan’s style.

For starters, he had to cross the continent, and that meant traveling by land unless he planned to make the trip unarmed. Some twenty-two hundred miles of highway lay between D.C. and San Bernardino. Amtrak needed fifty-eight hours to deliver him by train, leaving Bolan afoot at his destination. The alternative was driving: thirty-five hours to cover the distance at a steady sixty-five miles per hour, plus allowances for stops to fill his stomach and the car’s gas tank, maybe a break to sleep somewhere along the way.

In Bolan’s book, the road still beat the rails.

He could be unobtrusive when he wanted to, flying—or driving—underneath the radar. Bolan had perfected the art of “role camouflage,” wherein the average human eye saw what it was trained to expect, rarely looking past a standard-issue uniform or attitude.

In this case, he would be Joe Tourist, passing through en route to somewhere else. If asked, which was unlikely, he’d adjust his destination based on his location at the time, forever moving westward.

Bolan’s current ride was borrowed from a drug dealer in Maryland who had no use for a car these days. The pusher’s forwarding address was the Potomac River, but he’d carelessly forgotten to inform his friends and colleagues of the move. The car was a gray, two-year-old Lexus LS 10 sedan, nothing ostentatious about it unless you peered at the company logo and knew that the L in a circle had doubled the price for a midsize four-door. After Bolan had switched out the plates, he was ready to roll.

He kept in touch with Brognola from the road, adjusting his ETA based on weather, fatigue, construction delays and the car’s peak performance at twenty-odd miles on a gallon of fuel. In fact, it took Bolan forty hours and change to cross the continent, improving Amtrak’s time by three-quarters of a day.

His first stop was a chain motel, where Bolan slept six hours straight, dined twice in the coffee shop and left feeling fit for step one of the campaign he’d mapped out in his head on the long, lonely drive from D.C.

He was supposed to infiltrate Clay Halsey’s private army, prove that it was blitz-worthy before he brought the house down, and Bolan knew the militia chief would be doubly cautious with new recruits after finding an informer in his ranks. Bolan reckoned he couldn’t just show up and volunteer his services. He needed a foot—or a fist—in the door.

To that end, he’d contrived a plan with Brognola to make himself presentable, by fringe extremist standards. First, Stony Man Farm would prep a military file on Bolan—or, rather, on Major Matt Cooper, whose sterling combat record and assorted decorations hadn’t saved him from early retirement after he publicly challenged the fitness and patriotism of his commander in chief.

While that legend was polished and set into place, “classified” but still accessible to determined hackers, Brognola would prepare the scene for Bolan’s introduction to the NMM. Brognola, through the ATF, already knew the name and location of Halsey’s favorite watering hole. All he needed was a group of agents who could hold their own against the target and his vigilante inner circle, until Bolan intervened and it was time for them to take a dive.

Simple.

But simple plans, in Bolan’s world, had a disturbing tendency to go awry. A man living on borrowed time should take nothing for granted.

Assuming Brognola could find the proper cast—which seemed a certainty, given his pull at Justice and the wide array of undercover agents he could call upon—the set itself would still be fraught with danger. And if it fell apart, Bolan’s best shot at penetrating Halsey’s group would go to hell just as quickly.

Anything could happen once the players picked a fight. Halsey’s people could be armed, might even start shooting and hope for the best on a self-defense plea. Local jurors would be impressed by their grooming and righteous demeanor, opposing a band of shaggy barbarians.

But it would never go to trial, if Halsey or his men pulled guns. In that case, Bolan would be forced to intervene, and no one could predict how it would end, with undercover Feds and innocent civilians in the cross fire.

Best-case scenario: Bolan saved the day and was welcomed into the milia’s fold.

Worst-case scenario: a massacre.

Bolan could only keep his fingers crossed, as he prepared for his debut as Major Cooper. He had used the name before, sans rank, but nowhere that it would’ve reached Halsey’s ears. Meanwhile, the personality he’d picked for this Matt Cooper was entirely different.

After his rest, with hours left to kill, Bolan went shopping in Berdoo. He bought clothes suited to a former military man who’d fallen on hard times. Not living hand-to-mouth, but spending too much time alone and on the road from place to place.

He’d found the Harley Nightster at a used-bike shop, spent some of the money from the dealer back in Maryland to make the buy, and he was good to go.

Whatever happened next, Bolan had done his best to be prepared. If Fate stepped in to lend a hand—or strike him down—the Executioner would take it as he always had.

Facing the enemy and fighting back.