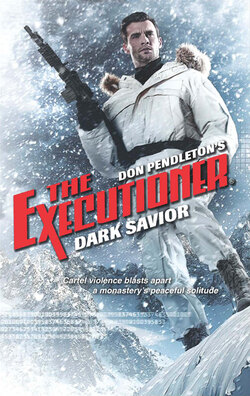

Читать книгу Dark Savior - Don Pendleton - Страница 9

Оглавление1

Over the Sierra Nevadas, California

“This is crazy,” Jack Grimaldi said. “It’s snowing like there’s no tomorrow. If I didn’t have the instruments—”

Mack Bolan interrupted him. “There won’t be a tomorrow for the target, if we wait. The window’s small and closing fast.”

“What window?” Jack asked. “Can you see anything down there?”

“It doesn’t matter. We’ve been over the terrain.”

“From photos, sure. What good is that when you can’t see the ground?”

“None at all,” said Bolan, “unless you, or one of a half dozen pilots skilled enough to drop me on the spot, is in the cockpit. And you’re the best among them.”

“Half a dozen?” Jack looked skeptical. “I would’ve made it three or four.”

“Well, there you go then.”

“All right, dammit. Flattery will get you anywhere. Almost.”

The aircraft was a Cessna 207 Stationair, thirty-two feet long with a thirty-six foot wingspan. Its cruising speed was 136 miles per hour in decent weather, with a maximum range of 795 miles.

Today was far from decent weather, any way you broke it down.

They’d flown out of Modesto City–County Airport, traveling due east. The storm had been barely a whisper in Modesto, but it was kicking ass in the Sierras.

Bolan’s chosen landing zone would be bad enough on a clear day, great fangs of granite jutting ten thousand feet or higher, bare and brutal stone on top, flanks covered with majestic pine trees and red fir. A drop directly onto any one of those could easily impale him, or he might get tangled in the rigging of his parachute and hang himself.

In theory, the jump was possible. In practice it was rated very difficult. But in a howling blizzard—for a novice jumper, anyway—it would be tantamount to suicide.

Bolan was not a novice jumper. He had more than his share of combat drops behind him, and had mastered new techniques as they developed, both in uniform and after he’d left military service, following his heart and gut into an endless private war. Today he’d be doing a modified HALO jump, a form of military free fall. The good news: the Cessna’s altitude meant there’d be little danger of hypoxia—oxygen starvation—or potentially fatal edema in Bolan’s brain or lungs. The bad news: with the blizzard in full cry, he could be whipped around like a mosquito in a blender, lucky if the winds only propelled him miles off course, instead of shredding his ripstop nylon canopy and leaving him to plummet like a stone.

All that to reach the craggy ground below, where the real danger would begin.

“We could go back and get a snowcat,” said Grimaldi. “Go in that way. Any small town up here should have one.”

Bolan shook his head. “That means an hour’s turnaround back to Modesto, grab the four-wheel drive, and what? Pick out the nearest town—”

“I’d land at Groveland,” Jack replied. “They’ve got an airport, they’re closer to the mountains—”

“And a snowcat maxes out at fifteen, maybe eighteen miles per hour if the visibility is good enough to risk that. That would mean five hours over mountain roads without the blizzard. The weather we’ve got now, it could be a day and a half on the road, and I could end up driving over a cliff.”

“Still safer than the jump,” Grimaldi countered.

“I can handle it. Just get me there.”

Frowning, Grimaldi said, “Your wish is my command. Five minutes, give or take.”

Bolan got up and started toward the Cessna’s starboard double doors, head ducked, crouching in his snow-white insulated jumpsuit. He secured his helmet, ski mask and goggles, and double-checked the main chute on his back and the emergency chute on his chest. He was laden with combat gear to keep himself alive once he was on the ground.

Assuming he reached the ground.

One of the side doors opened easily, caught in a rush of frigid air. The other required more of an effort, the wind pressing it closed, but Bolan got it done.

Outside and down below was a world of swirling white.

Bolan watched and waited for the signal from Grimaldi in the cockpit, answered with a thumbs-up, and leaped into the storm.

The Cessna’s slipstream carried Bolan backward, his arms and legs splayed in the proper position for exit from an aircraft, then the plane was gone and gale force winds attacked him like a sentient enemy. His goggles frosted over almost instantly, which wasn’t terribly important at the moment, when he couldn’t see six feet in front of him regardless, but he’d have to deal with that soon.

The insulated jumpsuit kept him relatively warm, but it wasn’t airtight, and the shrieking wind found ways inside: around the collar, through the eyeholes of his mask, around the open ends of Bolan’s gloves. The freezing air burned initially, then numbed whatever flesh it found, threatening frostbite.

From thirteen thousand feet, Bolan had about two minutes until he’d hit the ground below. Ninety seconds before he reached four thousand feet and had to deploy his main chute. If dropped any lower without pulling the ripcord, the reserve chute would deploy automatically in time to save his life.

In theory.

At the moment, though, Bolan was spinning like a dreidel in a cyclone, blinded by the snow and frost on his goggles, hoping he could catch a glimpse of the altimeter attached to his left glove. Without it, he’d have to rely on counting seconds in his head. A miscalculation, and he’d be handing his life over to the emergency chute’s activation device, hoping it would prevent him from plummeting to certain death in the Sierras.

Bolan brought his right hand to his face with difficulty, scraping at the ice that blurred his goggles. For a second they were clear enough for him to raise his other hand and glance at the altimeter. Eleven thousand feet, which meant he had to count another seventy seconds before deploying his parachute.

And what would happen after that was anybody’s guess.

If he didn’t survive this jump, it could mean a massacre. A dozen lives, and maybe two or three times more, depended on him without those people knowing it. If he arrived in time, unbroken, and could circumvent the coming siege...

A burst of wind spun Bolan counterclockwise, flipped him over on his back, then righted him again so he was facing the jagged peaks below. He kept counting through the worst of it and reached his silent deadline. Breathing through clenched teeth behind his mask, Bolan reached up to grasp the ripcord’s stainless steel D ring.

Instantly, he felt the shock of chute deployment, amplified tenfold by winds that snatched the ripstop canopy, inflated it, then fought to drag their new toy off across the raging sky. Bolan fought back, clutching the lines, knowing his strength was no match for the forces stacked against him.

When the snow cleared for a heartbeat, whipped away as if a giant’s hand had yanked a curtain back, Bolan saw frosted granite looming to his left and treetops rising up to skewer him. He’d missed a mountain peak by pure dumb luck and now he had split seconds to correct his course before a lofty pine tree speared him like a chunk of raw meat in a shish kebab.

He hauled hard on his right-hand line, rewarded with a change in course that might be helpful, if it wasn’t canceled out by the swirling wind. Bolan was going to hit tree limbs, come what may, but there was still a chance he could escape a crippling impact if his luck held.

As if ordained, the wind changed, whiting out the world below, and he was blind again.

Stout, snow-laden branches started whipping Bolan’s legs as he dropped through them. Seconds later, just as he had drawn his knees up to his chest and crossed his arms to protect his face, his parachute snagged something overhead and brought him to a jerking, armpit-chafing halt.

It didn’t take a PhD in forestry to realize that he was hung up in a tree.

Craning his neck, he couldn’t see the chute above him, only the steering and suspension lines above the slider, disappearing into snow swirl ten or twelve feet overhead. Below him, ditto: whipping snow concealed the distance to the ground.

He assessed his options. Hanging around for any length of time could test the ripstop nylon to its limits. If it had been weakened by a tear, Bolan’s weight—or any movements that he made while dangling there—could make things worse and send him plummeting to earth. Conversely, if he couldn’t free himself, he would eventually freeze here. Escaping from the parachute itself was not a problem. Each of his harness’s shoulder straps was fitted with a quick-release clip for the canopy, while other clips at the chest and groin would free him from the harness altogether. That was easy, but he couldn’t rush it; his first false move could finish him. Out here, in this weather, even a fairly short drop could be fatal if he broke his legs and became stranded in the storm.

Bolan remained immobile for a long minute, staring down between his dangling legs until an eddy in the storm gave him a fleeting glimpse of stone and snow-covered ground some ninety feet beneath his boots. A drop from that height would almost surely break his legs and crack his pelvis, maybe drive his shattered femurs up into his body cavity to spear his internal organs. The snow and any fallen pine needles below would cushion him a bit, but likely not enough to avoid crippling injury.

And in this storm, no help within a hundred miles or more, that was a death sentence.

So plummeting was off the table. He would have to climb down—slowly, cautiously—through branches wet and slick with snow and ice, fighting tremors from the cold and the onset of hypothermia.

Bolan considered dropping bits and pieces of his gear—the Steyr AUG assault rifle, at eight pounds loaded; his Beretta 93R, nearly three pounds; his field pack with survival gear, spare magazines and such, tipping the scale at thirty pounds—but balked at that. He didn’t plan on losing anything he’d carried with him when he left the Cessna, and whatever Bolan dropped into the storm from where he hung was very likely to be lost.

So he began his treacherous descent, shedding the canopy but not his harness, reaching for the thickest branch that he could see or feel, and hoping it wasn’t rotten to the core. When both gloved hands had found their grip, Bolan relaxed his arms enough from the chin-up position for his boots to dangle lower, searching for another branch that would support his weight. When they found purchase, he tested his foothold by slow degrees until he trusted it to hold his weight.

Which wasn’t quite the same as holding him.

When he released his grip above, the game would change. The gusting wind could knock him from his icy perch, or he could slip. It took the concentration and the balance of a tightrope walker for him to remain upright once both hands left the upper branch, his muscles straining as he slowly sank into a crouch.

Seven or eight feet covered, another eighty-three or so remaining. Bolan knew that as he neared the forest floor, the great tree’s branches would become both sparser and fatter, each more difficult to clasp with snow-slick gloves, making a drop more likely. Wind-whipped, cold and tiring, he resumed his painstaking and perilous descent.