Читать книгу A Nation of Shepherds - Donald L. Lucero - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление© 2004 by Donald L. Lucero. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Sunstone books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use.

For information please write: Special Markets Department, Sunstone Press, P.O. Box 2321,

Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504-2321.

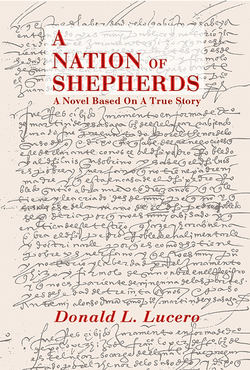

A NATION OF

SHEP HERDS

A Novel Based On A True Story

The pure Spaniard has always been

an agriculturalist by necessity,

and a shepherd by choice,

when he was not a soldier.

—Miguel de Unamuno

Spain was essentially

a nation of shepherds.

—John A. Crow

Spain: The Root and the Flower

PROLOGUE

On April 30, 1598, nine years before the founding of Jamestown,

Virginia, and the Popham Colony of Maine, and 22 years before

the Pilgrims anchored in Cape Cod Bay, Spain established a permanent colony in the high country of New Mexico. A Nation of Shepherds, which was inspired by this historic event, commemorates the lives of the 129 soldier-colonists and their families who were among the members of this first successful colonizing expedition.

No one portrayal of a historic event can be completely accurate. History is inevitably compromised in any telling. This is especially true when the author is attempting to compensate for things that have been told badly or, as in the present case, to offer a point of view not included in the previous tellings.

Despite the loss of documents in Mexico City and in New Mexico, during the Pueblo Indian Revolt of 1680, we have a surprising amount of factual information regarding the settlement of New Mexico. Among the major sources there are the documents published by Herbert E. Bolton and Charles W. Hackett; the incredible archival research conducted by George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey; a tract on the entrada written by Fray Juan de Torquemada; and notes on the archaeology of San Gabriel, New Mexico’s first capital. Although this information does not rival that provided by the works of William Bradford, John Winthrop, John Eliot, or Cotton and Increase Mather regarding the settlement of the New England frontier, the information is sufficient to both inspire one’s imagination and to prevent wild and arbitrary speculation regarding the colonization. While these sources reflect a Spanish colonial bias, they seem to record the facts, both favorable and unfavorable, allowing one to draw his/her own conclusions from the information presented. The gap in the documentation, of course, is the total absence of Indian sources. The Indians of New Mexico did not have a written language, and their oral histories regarding some key events appear to be either lacking or of very recent interpretation. This makes the reconstruction of this history from an Indian perspective a very difficult, if not impossible, endeavor.

The task I set for myself was to take an amazing story about real people and, as accurately as possible, tell it in a blend of fact and fiction. My obligation to history was to remain true to the facts, and to ‘get it right.’ In recounting the story, however, I was forced to fill a complete void in my knowledge regarding the lives of the Robledo family in Spain and in New Spain. In building the lives of these people, and in providing a hypothesis for their emigration to the New World, I tethered my imagination to what is known about the social and economic conditions of the historic period.

The narrative, which is written in a semi-documentary style, is divided into three acts or periods similar to the manner in which a Spanish play would have been presented. Except for two people, each of the individuals depicted in Period III, “The Kingdom of New Mexico,” was a member of the New Mexico colony. Antonio de Godoy, fictional chronicler of the expedition, replaces Juan Perez de Donis and Juan Gutierrez Bocanegra who were the actual secretaries of the mission. Godoy is patterned after Diego de Godoy, the Royal Notary who served in a similar capacity with Hernando Cortes. The fictional Godoy is charged with keeping the diary, and acts as cosmographer, and as mapmaker for the New Mexico expedition. These were written, described, and drawn by him in this story for the purpose of promoting Spain’s most remote Northern Kingdom.

Although this narrative is based on fact, I have used fictional elements to add drama, detail and explanation. The following will clarify which is which:

King Philip II and Hernando Cortes are historical figures whose actions were as described. Elvira del Campo is historical. Her crime, torture and testimony were as presented.

The religious facts are historical. Brother Joaquin Rodriguez, Senor Mattos, and Teo Machado are fictional.

Statements regarding the beginnings of Marranism, Inquisitional procedures, and the religion of the Marranos are from A History of the Marronos by Cecil Roth.

The journals attributed to Pedro Robledo the elder, are fictional. To my knowledge, no private diaries, letters, journals, or notebooks from the ordinary colonists survive from this period except for the epic poem, A History of New Mexico, published by Gaspar Perez de Villagra at Henares, Spain, in 1610, the letter from Alonso Sanchez to Rodrigo del Rio de Losa, and the letter from the officials of the royal army in New Mexico to the king.

The Indian attack on the train of 60 wagons carrying $30,000 worth of cloth actually happened. The plague of 1544 and 1555 recurred in 1575 and continued through a part of 1577. The deaths from hunger, thirst, and the effects of the cruel disease, are said to have exceeded 2,000,000, and occurred as presented.

Lucia’s carta de arras, which in this story is said to survive among the archives at the church in Valladolid, is fictional. The names of Catalina’s parents are unknown.

The geological, meteorological, calendrical, and astrometrical events were pretty much as described. The ‘march across the sky’ referred to when Onate leaves San Gabriel for his ‘expedition toward the east,’ pertains to George A. Custer and occurred in 1876.

The letters and reports attributed to Juan de Onate are historical. However, some of the descriptions of New Mexico and of its native peoples, are from the reports of Antonio de Espejo.

The reports attributed to Antonio de Godoy are historical, although the author is unknown.

The building of the acequia, or irrigation canal, mills, and church at San Juan are conjectured, although based on archaeological evidence, the needs of the village, and the engineering involved in their construction.

The building of the outpost north of San Juan and of the finca de San Pedro are supported by vague references among historical documents.

The unearthing of the dinosaur fossil, although historical, did not occur until 1947.

Certain words in the text regarding “a newer world,” “knowledge,” and “the quest” are from Ulysses by Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Quotations regarding the gypsies are from The Gypsies by Angus Fraser. The poem, The Snow Man, is by Wallace Stevens.

Each of the entries in the Epilogue is historic.

The information and characterizations made regarding the leaders of the New Mexico expedition are as accurate as can be determined from archival records. Although this is a work of fiction, the thoughts and dialogues I have attributed to figures in the narrative are based on research and on my understanding of the relevant people, places and events. There are certain scenes in which I have used my imagination, based on research, to create a thought process or even a conversation in order to give the scene its full expression. This seems totally legitimate as one can infer a thought process from a record of behavior. Archival records, however, are insufficient for helping us know New Mexico’s ordinary colonists. We have little information about them beyond their origins, and the physical description of the men and of their participation in some the colony’s leading events. Therefore, I have drawn New Mexico’s colonists to represent individuals from all aspects of Spain’s Third Estate, its ordinary people.

In many respects, the questions posed in this narrative echo questions about contemporary life. The year 1598, like 1998, was a banner year of optimism and confidence, the staging period for entree into a new century. Yet, despite this unbridled optimism and confidence, the apparent initial results of the colonial enterprise were abject failure, disintegration, and abandonment. I hope that the characterizations I have made regarding the colonists in respect to their participation in and contribution to this debacle have done no one a disservice. It is unfortunate that some of the colonists’ behaviors appear aberrational, startling, or even criminal, but they seem to be supported by research.

In the final analysis, may I say that I have the utmost respect and admiration for the achievements of these colonists. In individual drive, stubborn will, and indefatigable courage, they were the match of any people, and this is their story.

—Donald L. Lucero de Godoy

Dartmouth, Massachusetts

PERIOD I

THE KINGDOM OF CASTILE

The Tribunal

March 28, 1577

The sound was merely that of a hurried tap made with the butt of

the knife he carried to raise the occupants of the small house but

no one else. There was no answer.

The windowless house, which faced a stonewalled lane, looked like little more than a heap of puddled stone all gathered together. The man who had come up the cobblestone path stepped away from the doorway and looked up to see a whisper of white smoke, the remnant of a cooking fire, which rose from the stone chimney. He returned to the doorway, pressed his ear against the upper hinge and listened with every fiber of his being before continuing.

“Pedro,” he whispered as he slapped at the door with an open palm, his knife now replaced in its leather sheath beneath his dark clothing. “It’s Adan,” he said. “I pray I’m in time.”

Within the house, Luis, who had been sleeping before the open hearth, rose and moved to the poor bed where his aunt and uncle slept. Gently, he touched his uncle’s shoulder. “Tio,” he said, “there’s someone at the door.”

Pedro stirred, ran his fingers through his matted hair, and, dressed only in a nightshirt, rolled out of bed. Both he and his nephew appeared at the door where they were confronted by Pedro’s workmate.

“Pedro,” Adan said breathlessly as he stepped over the stone threshold, “they’re coming to get you. At first light, Pedro,” he warned, “they’re coming for you.”

“Who?” Pedro asked as he peered around the open door before closing it. “Who?” he asked again, as he struggled to put on his trousers and his boots.

“The Holy Office,” Adan answered as he assisted in closing the heavy door, the three of them lifting it so that it would clear the threshold. “They blame you for the prisoner’s escape and now he’s been killed.”

“Killed!” Pedro asked incredulously. “How? By whom?”

“A posse sent looking for him by the Inquisition trailed him to a robber’s cave, and he was killed by them before he could reveal his secrets regarding additional backsliders. They say you ruined years of work by allowing him to escape.”

“How could he be responsible?” asked Catalina, who was now standing behind her husband in the candlelit room. “Pedro is a scribe only,” she defended in her peculiarly soft and sweet voice. “He’s not responsible for prisoners.”

“The prisoner was de los Santos,” Pedro replied as a way of explanation, “one of those betrayed to the Holy Office by the wife of Alonso de Maya. She was the one I told you about, Catalina. What is it now . . . eight years ago? Elvira del Campo, who was charged with practicing Judaism in secret . . . not eating pork and with putting on clean clothes on Saturday. The Edict of Grace1 had been published, and the Term of Grace2 had passed, and the poor woman was being required to confess. You should have heard her, Catalina,” Pedro said. “I was working in the room next to the chamber where she had been taken and where she was being told to tell the truth. She was subjected to the jarra (jug)3 and then to the tying of the arms. ‘Senores,’ she screamed, over and over again ‘remind me of what I have to say for I don’t know it!’ A cord was applied to her arms and twisted and she was being admonished to tell the truth. ‘I did it!’ she screamed over and over again. ‘I did what the witnesses say. I don’t know how to tell it.’ I went next door to plead for leniency, but they wouldn’t allow me to enter. It was obvious that they wanted her to confess and that there was some proper way for her to say it. She was given 16 turns of the cord until it broke. She would have done anything—said anything—to end her torture,” Pedro said, “denouncing and perhaps even inventing the names of others whom she claimed were guilty of lighting special lamps on Friday evening, observing the Day of Atonement, or some other trivial action performed absent mindedly or by mere force of habit. Who knows of what, if anything, de los Santos was guilty!” he exclaimed. “I was merely being asked to escort him to the old Castle of Maqueda. We were within sight of the towers, Catalina. I could see them in the mist—four towers, plain and severe. We were almost there when his mule tumbled over the side of a ravine and he was gone!”

“It doesn’t matter, Pedro,” Adan said. “Someone’s got to be the scape-goat and this time it’s you. The calificadores will find ample justification for further action, and your punishment will be severe: the frame, the funnel and the water, Pedro. If you survive the torture and are convicted, you’ll be sent to the galleys. You’re done here, Pedro,” Adan said in resignation. “Perhaps you can make your plea to authorities in Toledo, but in Torrijos and Carmena, you’re done. We must go!”

“How go, Adan?” Pedro asked while looking at his wife as though seeking an answer. “Carmena has been our home for generations. How can I be made to leave?”

“You have no choice, Tio,” Luis said, as he gathered his uncle’s cloak from its place on the wall. “Go with Adan, Tio, go!”

“They’re right, Pero,” Catalina added using his pet name. “You can go to my papa’s home in Toledo. He’ll hide you. We can join you there.”

Adan, who had been standing before the open hearth, now moved to the oaken table where he sought to help Pedro gather his belongings. “That may work for awhile, dona Catalina,” he said, “and it’s good that you have a place to go. But they’ll follow you and compel Pedro’s return. He has a few days—perhaps a few weeks at most. Maybe your father can help you get to the coast where you can make use of the license for overseas travel you obtained a few years ago. That license may be your ticket to freedom. Anyhow,” Adan said, “we’ve no time to talk. They’ll be here at first light. Take only what’s required.”

“Go, Pero,” Catalina begged. “We’ll follow you.”

“They won’t let you,” Pedro replied. “That’s how they’ll get me to return.”

“We’ll find a way to get them out,” Adan promised. “We’ve done it before, and we can do it again. I’ve got mules waiting below the walls.”

“Go, Tio,” Luis urged while putting a comforting arm around his aunt’s shoulder. “We’ll meet you in Toledo. Two days only. Mi Tia, Ana, Diego, mi tocayo, Luis and Lucia. We’ll meet you in two days!”

“At the Pena del Rio,” replied Pedro who was at his best when designing and executing a plan, “you’ll have to avoid the Moorish bridges and the river is the most shallow there. I’ll have lines strung across the Tagus at the great rock. We’ll use them to steady the cart and to pull you across. Look for the towers of Malpica, Luis. Use them to guide you,” he stated emphatically as he held and kissed his wife for the final time. “Day after tomorrow, Luis,” he said as he stuffed several items including his journal into a leather bag. “Wait for light, Luis,” he added as he and Adan moved though the open doorway. “Wait for light.”

***

As Catalina and Luis approached the river, they traversed the barren slopes of the Castilian meseta, a high tableland of fertile plains, broken here and there by a lone olive tree, piled gray stones, sparse scrub, and a tangle of undergrowth all dusty-gray but excellent cover for game. As they rode in the darkness, Catalina confirmed what Luis had been hearing for some period—hounds in full cry apparently in pursuit of game. They tried to assure themselves that these were the sounds of an early hunting party, but both knew this to be unlikely. They were, they feared, the ones being hunted.

Catalina and Luis had for some period been picking their way through a riverine forest of tamarisk and willow in their attempt to reach the river. Luis, who was holding his three-year-old cousin of the same name, flailed at the oxen with his right hand. The cart, which was filled with the two adults and a locust of children, rose and fell with great jolts as it bumped and rocked its way towards the steep bank.

Suddenly—almost miraculously—they emerged from the tangle and were at the water’s edge where they were confronted by a raging torrent now swollen with rain. Luis dismounted and entered the slower water that flowed near the bank, testing its depth with his oaken pole.

“Here, Tia,” he said urgently. “We can enter the water here.”

“How do you know this is the right place, Luis?” his aunt asked in a whispered tone as he reentered the cart. “Your Tio said to wait for light, and we don’t have the towers to guide us.”

“It will be all right, Tia,” Luis replied. “We may be a little above the rock, but the current will carry us downstream where the lines will stop us.”

“No, Luis,” his aunt said, holding her son Luis and his four-year-old sister Lucia to her side. “Let’s wait. It will only be a short time till light. Then we can see.”

“We have no choice, Tia,” Luis replied as he prodded the oxen with the point of his long goad. “They’re behind us. We’ve got to go!”

The oxen were balky. The sound and the smell of the muddy water, which carried a river of debris, frightened them. They required the whip to compel them to enter the raging stream, a dark swirling torrent which they could now also feel, taste and see . . . and it was terrible. Luis immediately realized he had made the wrong decision, that he had chosen the wrong time and place which was more than two harquebus shots above the spot suggested to him by his uncle. His frightened beasts, tethered to an oaken shaft that was but an extension of the framework of the cart’s body, plunged into a deep hole. His beasts, with only their horns and eyes visible, bellowed with fright as they sought firm ground. Luis again entered the water where, holding on to the horns of the nearest beast, he attempted to turn his team toward shore. Momentarily, the docile animals quieted and began to turn with the current. The cart, however, snagged on an obstruction, lurched forward, and then overturned, dragging its massive beasts below the surface. The wooden frame and the bows of their harness, which had assured their bondage and servitude, now guaranteed their death.

As the cart overturned in the intense current—with the frame yet bumping and reeling as it dragged along the ragged bottom—Diego was thrown into the turgid stream. He was pressed against one of the wheels, a solid barrier of three pieces, which was attached to the one axle. He struggled to remain upright as he held onto his five-year-old sister, Ana, who had entered the water on his side of the cart.

“My babies! My babies!” His mother cried as she desperately flailed in the raging water. Diego could not see her for both she and Lucia were on the other side of the second wheel.

“I’ve got Ana, Mama,” he cried as he fought to hold on to her. “I’ve got Ana.”

“And Luis?” she screamed.

“I don’t know, Mama,” he cried as he searched the water around him. “I don’t see them.”

Diego, six-years-old, and the oldest of the four children, held Ana around her waist as the water worked to tear her from his grasp. In an instant, the rushing water pulled her thin body from beneath his arm.

“Diego,” she said quietly. Just his name. Nothing else.

“Hold on to my neck, Ana!” he cried as he tried to work his way around the wheel, his move encumbered by his hold on her wrist. “Hold on to me, Ana!” he yelled in desperation. “Don’t let go!” he cried as the first light of dawn came up on his face.

As he inched his way around the ancient wheel, the Stygian water filled his mouth and nostrils with mud, and he feared that both he and Ana would also be swept away. It was beginning to become light now, and he thought he could see the distant shore, although the muddy water which cascaded over his back and shoulders made it difficult to see. Ana’s thin arms encircled his neck while the cart reeled and groaned, turning this way and that as it moved down the streambed. In the dim light he could see the oxen’s yoke. One of the two bow-shaped pieces of wood which had been inserted from beneath the neck of one of the oxen had broken. Its occupant was now gone, and hanging from below the horizontal bar was a hook to which a draw line was still attached. He released his grip on Ana’s wrist and reached for it, hoping to put it to some use. “Hold on, Ana,” he begged. “papa will get us.”

As he reached for the rope, Ana began to lose her hold on him. He could feel her small hands grasping and tearing at him as she slowly slid from her place on his back. And when he turned, he could see her, a beautiful elfin doll, who appeared to be suspended on a cushion of air, the cold black water revealing a deep gash on her forehead. He reached for her. She looked back at him with eyes seemingly filled with wonder, said nothing, and then she was gone.

***

Pedro stood with his father-in-law’s overseer, Tonio, on the south bank of the river as the sun came up shining on the red of his hair and beard. He was distressed by what he saw. The lines which he and Tonio’s men had strung across the water the previous evening were now largely submerged by the flood waters, their ends only apparent where they emerged from the angry waves and were tethered to a tree. It was a bad plan, he said to himself, his blue eyes searching the far bank. He realized that these floodwaters should have been anticipated. They might be coming from as far away as the Sierra de Albarracin. The river, which cut into limestone rocks there, flowed through narrow, sinuous valleys with deep canyons and abundant ravines and was often in flood from unseen storms. It runs more peacefully here, Pedro said to himself. But above—and also below Toledo where it again flows through narrow, steep-edged trenches formed by quartzites and shales—the river could be deadly. “I should have anticipated this,” he said to Tonio as they surveyed the far bank. “We must signal them and tell them not to cross.”

Pedro pulled at his beard in apprehension as he searched the far bank in the early light. He was concerned that his family had not yet arrived. He could see various items of flood debris—logs, a market basket, an unshorn lamb—as they moved downstream. He had not taken notice of a circular shaped object that now broke the surface, but as the object moved slowly down the streambed and lodged on a rock directly across from him, he realized that it was a segmented wheel, and that it was attached to a cart. Pedro immediately entered the water but then retreated, reaching back with his right hand at the rope being offered him by Tonio. He then again entered the water as did Tonio and two of Tonio’s men, pressing their lean, muscular bodies against the tow ropes but unable to move forward due to the tumble of the water.

Eventually, the men were able to attach a rope to the upturned cart and to drag it ashore. Ana’s body lay but a short distance below the great rock, and was found later that morning. The roots of a tree had snagged her body and that of a fallow deer. However, despite extensive searches, which were conducted on both banks of the river, they were unable to find the bodies of the two Luises.

***

Although a cart had been offered to carry Ana from where she had been found, Pedro refused to relinquish her care to another. Accompanied by black-robed men, whose mumbled prayers seemed to lack both rhyme and reason, he carried her from the bank of the river to the home of his father-in-law, Alonso Lopez, where Catalina, Diego and Lucia had been taken. Here Catalina and the children were lodged in their mother’s old bedroom, the room in which Ana and each of the children had been born. Surrounded by a throng of black-robed men, Ana was placed on her mother’s bed, which had been draped in black. In the flickering light of the priests’ candles, Diego and Lucia could see Ana wrapped in a small cotton blanket and cradled in their mother’s arms as if asleep. Outside the room, Pedro’s grief exploded in angry words regarding the unwelcome procession from the river. In his anguish, he likened it to “the pagan observance of the Robigalia,” the procession through fields of corn to pray for the preservation of the crops from mildew. “My God,” he exclaimed to his father-in-law who had attempted to console him, “have they nothing better to do? God save us from them!” He later apologized to the priests for his outburst, but they often had to deal with the peoples’ anger as they provided for their spiritual needs and had been little put off by his display.

Catalina, ordinarily frail-looking, gentle, and perhaps a bit hesitant in her manner, had inevitably begun to crumble. Her conduct, if not yet that of one insane, was certainly that of an individual laboring under extreme distress. Mute and benumbed, she first lay with Ana in her room until the child was taken from her to prepare her for her burial. She then sat alone in her cell, an alcove which opened onto the zaguan, or vestibule, but which was completely dark and had previously served only for sleeping. There, draped in black, she sat with her head seemingly nailed to her hand and appeared to be involved in a battle to retain her senses. Asking repeatedly for Luis, she seemingly did not comprehend the responses she received. She sat like this through the day, refusing to leave Ana who had now been returned to her in a small pine box. Before Ana was removed from her room to the church, Catalina required that Pedro pry open the pine shell in which she had been placed. Then, with no alteration of demeanor, she looked at, and even put her hands on, Ana’s body, which was now wrapped in a white linen shroud, perfectly white and clean. Afterward, Catalina became totally closed off and listless.

The coffin was placed on a poor catafalque before the great cathedral, a vast edifice of marble and granite, where the coffin was opened again, the box of wood pried apart, and her cerements again revealed. The grief stricken observers, among whom were Catalina’s children, were required to affirm that the body was truly Ana’s. Then the coffin was closed again and draped in black.

Night was coming on by the time a cart was provided and the grim cortege was arranged in the cobbled street before the cathedral. There King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel had prayed before the tomb of their great- great-grandfather exactly a hundred years before. Catalina, supported by Pedro and followed by her two surviving children, walked barefoot behind the cart with a crush of priests chanting prayers for the dead as they began to wind their way toward the river.

An opacous cloud of fog hugged the earth, “the heaviest cloud in the world,” noted Diego, and soon it became so dense that they were barely able to move along the road. They pushed on, however, stopping seven times along their route of desolation until Catalina, whose strength had been ebbing, was unable to walk any further. She was placed in the cart with Ana, and again they went forward.

The procession continued along the river until the mourners arrived at an ancient and beautiful stone bridge across from which was the burial place. There the coffin was opened for a final time. Catalina kissed Ana’s hands and feet. And then, for what seemed like hours, the small group, wrapped in their plain trappings, huddled around the small coffin, their wax torches guttering in the wind. The service, like the procession itself, was the essence of simplicity and equality. “God is the true judge,” said one of the priests. “May her death be an atonement for all sins she may have committed, and may she come to her place in peace.”

Pedro felt they were speaking of him and not of Ana. For what sins could this child have possibly committed? he asked himself.

With the final words of the priest now spoken, they tore their garments to put the mark of a broken heart upon their clothing. Then, with the dark of night nearly upon them, they picked up the small box and lowered it into the virgin ground, the sound of the first fall of earth on the coffin providing an air of finality

_____________

That evening after their return from the burial ground, Pedro and his father-in-law walked through the entire house making an inventory of its contents.

“You’ll take whatever you need Pedro,” his father-in-law said.

“I’ll repay you, don Alonso,” Pedro responded quietly as they made their way from room to room.

“We’re not going to worry about that now,” the older man said. “You’ll take what you need. And when you get to Sevilla, the cargo there will also be yours.”

“I can’t repay you for that, don Alonso,” Pedro said. “I don’t think we can accept it.”

“You’ll accept it, damn it!” his father-in-law said with a brief display of anger. “It’ll be your nest egg. It was to go to your cousin, Miguel de Sandoval, God rest his soul. But with him dead now, and with his wife, Catalina Sanchez now returned from New Spain, it’ll go to you.”

“But if I go, don Alonso,” Pedro said emphatically, continuing the conversation in which they had been engaged, “it won’t be as a fugitive.”

“However you go, Pedro,” his father-in-law responded as he closed the door to the storeroom they were leaving, “your days here are numbered.”

“But as a free man,” don Alonso, Pedro said, “never as a renegade.”

“Oh, your pride, Pedro,” Catalina’s father responded in exasperation, his lips tightening as though he was trying to control some emotion. “Your pride kept you from working for me, Pedro, and it’s going to get you killed.”

“It wasn’t my pride that killed my children, don Alonso,” Pedro responded. “It was my fear . . . and my stupidity.”

“What stupidity?” the older man asked as they ascended the worn stairs from the zaguan. “No one could have known the river would be in flood, Pedro. Do you think God is under an obligation to give notice of a coming misfortune? No one could have known,” he continued softly, his anguish now spent. “It was just an accident, Pedro,” he said while turning away from his son-in-law so that Pedro would not see the tears. He was silent before going on. “It was a tragic accident, that’s all,” he said quietly as he continued covering mirrors and emptying standing water throughout the house.

Pedro sat on a stool that stood on one side of don Alonso’s estrado de cumplimiento, or state salon. From there he could see the pictures, the heavy, carved wooden chests, the delicate chests of drawers and the sideboards inside the room, as well as the salon’s balcony which stood outside its full length windows whose silken curtains now billowed in the wind. The balcony of forged iron, the angles of which were decorated with balls of copper, overlooked the towers and spires of the city and faced the damnable river, a sullen dark thing without obvious movement. As he looked at the balcony through the open windows, a rush of emotion seized him as he thought of the memories the balcony evoked. It was here that he had first held Diego and each of his children.

“She was the most perfect child,” Pedro said of Ana, speaking more to himself than to Catalina’s father as he rose and moved toward the windows. “So bright and eager to learn. Nose to everything. If it was there, she had to know what and why. Questions all through the day,” he said of his five-year-old. “And Luis,” he continued with a catch in his throat, “he was just a baby. My poor innocent lambs,” he said. “There’s been such suffering and I alone am responsible.”

He stood for a moment, lost in his own thoughts, and then continued as though trying to provide an explanation to himself. “I ran because I believed it to be the right thing to do,” he said. “The Inquisitors would have trumped up some charge against me. You know how they are. They might even have tried me for heresy. Perhaps I would have been acquitted,” he said, “but who can take the chance? Persons have been known to languish in prison for as long as 14 years before they might be pronounced free of guilt or blame. I couldn’t risk it, don Alonso,” he said in resignation.

The old man was silent for a long time, and when he responded, it was with a voice full of sadness. “I never wanted you to work for the Inquisition,” said don Alonso, pulling his cloak about his shoulders. “I felt it unseemly, Pedro. Baptism has done little more than convert a considerable proportion of our people from infidels outside the Church to heretics inside it. And these searching inquiries into our conduct, and the punishments meted out for those of us found guilty of backsliding, are not only unseemly but criminal,” he said. “I didn’t want you to have anything to do with it.”

“And I thought of my job as only that of a scrivener,” Pedro said. “I was lying to myself, don Alonso,” he said sadly. “Now I feel like La Susanna, carrying on an intrigue with a Christian, disclosing our secrets, and bringing all to ruin. My interests were only in manuscripts and the law,” he said. “What have I done?”

“You’ve done nothing,” his father-law stated emphatically. “You give yourself more blame than you’re due. But I know your value, Pedro” he said. “You can do whatever you put your mind to. You’ll start on a new course and we’ll be partners.”

“But passage, don Alonso. How do we gain passage?”

“Everything’s for sale here,” his father-in-law responded as he joined Pedro at the balcony’s entrance, “titles of nobility, the offices of regidor and jurado, letters of legitimization for the sons of priests. Everything. The crown needs our money,” he said gesturing with his hand as though holding a fistful of coins. “My God, Pedro,” he said, “what does don Felipe owe, 37,000,000 duats? All grants have been suspended, Pedro. He can’t pay his bills. Don Felipe needs our money. It won’t be difficult to gain your passage,” he said with the air of one who has learned how to deal successfully and shrewdly in the world of commerce and politics.

For a few moments they stood looking at each other before Pedro’s father-in-law continued. “You’ll leave tomorrow, Pedro, and Tonio will see you to the coast.”

“I don’t see how we can go, don Alonso,” Pedro responded. “Catalina . . . Catalina can’t travel.”

“You’re right, of course,” his father-in-law said as he held back the curtain to get a better view of the night. “And under ordinary circumstances she’d remain with me until she was better. But she’s like her mother, Pedro,” his father-in-law said regarding his daughter, “seemingly fragile, but strong when it comes to her family. Her place,” he said, “is with you. You must try to distract her from her melancholy. Stay away from the towns and villages as much as you can, Pedro, and buy your provisions along the road. Avoid the milliones,” he said, referring to the taxes which were imposed upon everything one ate. “You should be able to buy everything you need along the way. I’m going to the corrals now,” he said, throwing the skirt of his cloak over his shoulders. “I must see to the mules.”

“I’ll go with you,” Pedro said, gathering his cloak about him.

“No,” his father-in-law responded, while taking his broad brimmed hat from its place near the glass doors. “You must get ready for tomorrow and there must not be too much noise about it,” said this shrewd and careful man. “You’re a good man, Pedro,” he continued, with the tears again welling in his eyes. “You must not grieve,” he said as he began to provide the advice which a father must give to his son. “You must look for happiness,” he said placing his hand on Pedro’s shoulder. “You must accept your lot, Pedro. You must say to yourself, ‘Perhaps it was for the best.’ I hope and pray that all goes well with you,” he said as he readied himself to leave the salon. “You’ll always be as my own to me, Pedro, and I want only for your safety.”

Pedro entered the gallery and watched his father-in-law as he closed the street door below him. As he stood on Catalina’s balcony of joys and sorrows, he recalled with an effusion of emotion that moment in which he had sat there with Diego looking over the tiled rooftops and spires of the ancient city and toward the Tagusian moat. He had often sat there with his father-in-law, listening to the music being sung at the cathedral, but on that particular evening with Diego there had been no music, the hushed village seemingly awaiting a momentous event.

_____________

The sky had been a ghostly rose and violet in color, lilac shadowed with majestic serenity. Pedro and Diego had been sitting there quietly while Pedro engaged in the long process of filling the bowl of his pipe with tobacco he had taken from a pouch in the pocket of his shirt. Then, suddenly, without warning, an incredible flock of perhaps a hundred or more swallows, swooped down out of the sky to the top of the balcony and then off again into the amethyst heavens. They flew in a line, one after another. At times, the swallows came within inches of their faces, the glossy blue-black on their upper parts contrasting beautifully with the white on their outer tail quills. They continued in this manner, swooping down with a delicate grace, flicking the pools of street water with their dark wings and then, with a shrill twitter, returning to the open sky. They continued like this for many minutes during which Diego and his father seemed to be members of the flock, participants in their aerial display.

“Papa, Papa! Look at them, look at them!” Diego had squealed. “Where’d they come from?” he asked, as he peered into the heavens, hoping that by some miracle they would return.

“They’re coming home, Diego,” his father had replied as he returned to the task of filling his pipe. “Home from the wilderness where they nest during the winter. I’ve not seen it, Diego,” he said, “but it’s called Las Marismas—the tidelands—and it’s a place where millions of land, water, and shore birds go to find food during our long winters. Birds come there from Asia and Africa and from all over Europe. Geese from Denmark, starlings from Germany, and the beautiful white egret from West Africa, among many, many others. It’s said they have purple herons, and bee-eaters and hoopes without number. Someday, perhaps you’ll see it, Diego,” he had said, not realizing the prophecy of his words. “It’s near Sevilla, but my travels aren’t likely to take me there.

“Birds, Diego!” he had exclaimed. “It’s all about birds. Each town and village is watched over by a guardian bird which, according to the day and hour, renders the town pleasing, ravishing, or disquieting. I’m not sure what bird guards your grandfather’s home, but Carmena is watched over by a dove. Adam is said to have named them and perhaps this is true, for they’re ancient auguries of that which is favorable or unfavorable,” he had said, beginning one of those tales for which he was justly famous.

“When Noah’s ark landed at Mount Ararat after the great flood, he let loose a raven which flew off into a blackened sky. For countless days, he awaited its arrival, but it did not return. He then sent out a dove, and it returned because it couldn’t find a place to land. Later,” he had continued, “he sent out the same dove two more times. On the second flight, it returned with an olive branch in its mouth. It was a sign, Diego, a sign to Noah that he, his family, and all the animals could come out of the ark and begin a new life.

“Good old Noah,” he had continued. “He was the only righteous person of his time. And he took enough birds and animals aboard his ark to re-populate the earth. He knew, as we’ve all come to know, that birds are the best indication of a good climate and country. And now it’s said that the birds of the monsoon are seen as messengers of hope, for if they come, they foretell a year of plenty. If they don’t come, people know that there’ll be famine throughout the land. They’re symbols of all things wild and free and are a blessing. We’ve only to read their signs, Diego. We’ve only to read their signs.

“Over there, mi ijiko,” he had said, gesturing towards the northwest, “beyond Carmena and Avila, that’s where your abuelo and I saw an enormous flock of stilts coming from the north, from France where they’re said to nest. You should have seen them, Diego,” he had said with enthusiasm. “There were hundreds of them, the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen. Their necks were long, and their bills were, too, thin and very straight. They flew with their endless legs trailing behind them. I’d seen them before. On the Alberche below the walls at Escalona, their legs so long that they had to tilt their bodies to reach the ground. But when they fly, Diego,” he had continued, “they’re majestic. White with black wings and with a call like the yelp of a small dog. Your abuelo and I were on our way to Salamanca to visit the university. ‘Following knowledge endlessly like stars sinking below the horizon,’ is how my papa described it.”

“Stars, how stars, Papa?”

“Well, not stars, exactly” he had said, peering into the fading light and pulling his collar about his neck. “At least not the kind we see in the sky. But hopes and dreams. Salamanca is where your grandpa and I went in search of my education.”

“Further than Carmena, Papa?” Diego had asked. “Maybe we can go someday, Papa,” he had said, emphasizing the “we.”

“Perhaps, Diego,” his father had answered as though considering the possibility. “We’ll see, Diego,” he had said. ‘”We’ll see.”

_____________

Pedro leaned against the wrought iron rail and thought of the sentiment expressed by his father-in-law, a sentiment he wished his father had also held: that it’s better to dare mighty things than to count oneself among those that neither enjoy much nor suffer much. “You must not grieve,” his father-in-law had said. “You must look for happiness, for to do otherwise is to live in a gray twilight and know neither success nor failure.”

We’ve suffered much, Pedro said to himself, and Ana, Luis and my poor nephew paid the ultimate price. The joy of his existence had been rooted in Castile and now God who had given these children to him had also taken then away. “I’ll keep you in my heart,” he said aloud to his beloved dead. And with no further time to contemplate their loss, left the balcony.

This Crag of Sorrow

“I can go by myself, Papa,” Lucia pleaded in her small voice as she stood beside her hooded mule, the hem of her nightdress trailing in the mud. “Like Diego,” she said. “I can go by myself.”

“Shh,” her father responded as he put his finger to her lips. He then placed her astride her mule, the scent of her—of angel water and sleep—sweet in the damp cool air. “We’ll see, ijika,” her father promised as he placed her in her saddle. “You’ll go with Tonio for now,” he said, “but we’ll see. We’ll see how it goes.”

Lucia, appearing spare and wan, held her thin arms tightly across her chest refusing to touch the withers or mane of her beast. The corners of her budded lips drooped slightly at their edges as she observed the remainder of her family waiting in the darkness. While she sat there, her father so close she could have reached out and touched him, she looked down into her mother’s sedan chair and could, she thought, make out her mother’s knees and her clasped hands which were folded in her lap. It was one of those moments, however, when one did not know whether what one was experiencing was real or imagined. She knew that her mother’s face and neck were hidden from her view, and that it would have been impossible for her to see the auburn hair, long, white throat or those blue-green eyes which she wished were her own. But would she have been able to see her mother’s hands? she asked herself. Or was this just the way she knew her mother would be seated? She did not know. What she did know was that she could see or sense movement within the sedan chair as her mother rearranged her seating.

Within the chair, Catalina felt for the correct placement of her feet on top of the Moroccan cushion which she had asked to take from her mother’s parlor. She had, until this moment, been brooding and immobile, locked in a deep trance from which she could not seem to escape. However, with the realization that she had to provide for the welfare of her remaining children, she had broken through her passivity, and assumed an active role in the preparations, even seeking to take some precious objects from her parents’ home to which she would likely never return. The darkness, as well as the haunches of her lead mule, obscured her view forward, although she knew that her position in the train, as in life, was immediately behind her husband who now sat on his mule ahead of her. As she settled back within her enclosed settee, which rested on the haunches and shoulders of her mule team, she could, through the dark clothing and the black shawl that she wore, feel the cold leather of the sedan’s seat and back as they pressed against her frail body. Additional mules, coughing and wheezing in protest, carried the trunks and valises containing the meager clothing and household goods they had obtained from her father. Once mounted, the family waited in silence.

The stars and the moonlight cast shadows against the walls of the tortuous passageway, a street so narrow that the overhanging roofs of the adjacent homes nearly touched. The normal qualities of the stones of this passageway were unrecognizable in the veiled light. The sky, reflected in the family’s tears and in the pools of moisture that had collected from the evening’s heavy dew, had a timeless quality about it that did not identify it as either a day or night sky. In the darkness, Lucia could barely distinguish one silhouette from another as additional muleteers came up the cobbled path. She tried to tell whether or not any of them were men who worked for her grandfather. One of them—whom she identified by his ‘limp of Lepanto’—was Tonio, her grandfather’s mayordomo or overseer. It was unlikely she knew any of the others. Still, she wondered who these men were who were about to lead them into the night. The light had the cast of sadness. The sounds were those of anxious hooves. And the smells those of working men, leather, and mules.

In the darkness, Tonio and his head packer, or cargador, rechecked the seating of every load, each of them walking down his own side of the mule train, the clack of their double-soled boots resounding in the darkness. Tonio, who was responsible for the safety of his charges, his men, and his beasts, wanted to assure himself that his muleteers had done their work well as he felt for the correct placement and security of each item. Saddle clothes, grass stuffed pads, grass cinch, straw mat coverings—nothing was overlooked in his inspection. Once the examination was completed, he mounted his own mule which stood at the front of the train. Then with the cargador’s “Adios!” and Tonio’s response of “Vaya!” the mules, led by a bellmare and divided into four strings, began to inch their way down the steep cobblestoned corridor and away from the house on one of Toledo’s highest hills. Then, although admonished by his father not to look back, Diego glanced one final time at his grandfather’s home which now appeared empty, dark, and desolate, and at its exterior balcony as he rode beneath it. He searched in vain for the spot in the wall where he had hidden his white stone as a prayer to assure their return and worried that it would not be able to work its magic. However, his attention was quickly diverted to more pressing matters when one of his mother’s mules slid into his as they exited the corridor.

Through shadowed, Moorish streets like dark ravines, the family moved along steep, narrow corridors paved with cobbles taken from the muddy, red bed of the Tagus. They rode past crowded whitewashed houses, which faced terraced streets, the corridors overhung by glazed verandas or by wrought-iron balustrades enclosing narrow passages. The silence was broken only by the sound of hooves and of water splashing into stone basins.

As they neared the river, they rode through the ancient Jewish quarter of Toledo, virtually a town in itself, situated in the southwestern portion of the city. The southern section of the district sloped down an incline to the bank of the Tagus and included a fortress once known as the ‘Jew’s Citadel.’ Here, with the clatter of their mules the only sound to be heard they passed through the battle-scarred walls of the fortress, away from the roofs, towers, and domes of the ancient city and began their steep descent to the river.

Galiana’s Palace

A few plain trees and Spanish poplars marked the road the Robledo party traveled. There were many rocks, and the fields, which at winter’s end had been a broad stretch of parched meadows, were now covered with the emerald grasses of an early spring. The hollows of dry waterbeds were choked with tamarisk, their fine, feathery branches and minute scale-like leaves now moving in the pristine air. A gentle breeze sprang up along the deeply etched bed of the Tagus, bearing the scent of mud and dry leaves and, incongruously, the faint odor of animal dung, the remains of a previous passage.

As they rode alongside the river, which was bordered by white-trunked poplars and giant tamarisks, the sun began to tip the horizon, and the landscape in all directions became clearer. While riding, they began to see the harsh uplands long-celebrated in the annals of Spanish history. Streams interlaced the area of scrubby brush, rock rose, heather, and cork oaks, while in the heights, deer, foxes, lynx, wolves, and wild boar were to be found. A single cloud, like tufted cotton, was ridged against the sky as they headed toward a distant hill.

Riding through the area, Pedro thought of how, during visits to their grandfather’s home, the children had begged to be taken to see the local wonders. Scattered throughout the area were numerous prehistoric sites, all boasting megalithic ruins composed of huge stone monuments and tombs. Also in the area was an ancient ghost town once protected by a fortress, while odd stone boars or bulls—verracos—decorated nearby castles. Each of these sites had presented the possibility for an excursion and a chance to enjoy life in the open air but would have required a long day’s ride. Therefore, instead of visiting one of these, he had last taken them to Galiana’s Palace and the clypsedra, or water clock, which had been one of the wonders of the Moorish world. The water clock, which lay among the ruins of a Moorish palace, or alcazar, on the banks of the Tagus River, had once consisted of two large stone basins that filled and emptied themselves of water every lunar month in time with the waxing and waning of the moon. It was said that in 1085, some 50 years after the Christian re-conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI, Alfonso VII, his grandson, curious to learn how the clock worked, had it taken apart. Unfortunately, his craftsmen, as skilled as they were, had been unable to reconstruct it. Pedro had presented the story to them as an allegory. “Sometimes,” he had said to his children, his blue eyes seemingly reflecting the late winter sky, “it’s best to accept things as they are, to enjoy them, to marvel at them, or to suffer the pains of their sorrows without question. However, at other times, it’s best to search for meaning.”

To accept things as they are, he thought to himself as they rode by the palatial ruin. His hallmark had always been his cheerful acceptance of life in its simplest and most sublime terms—with all its tragedy and all its enveloping mystery. Now, however, he, too, searched for meaning in the family’s recent tragic events and could find none.

* * *

As the members of the mule train rode to the brow of a rounded hill, a little beyond where they had once dismounted for their walk to Galiana’s Palace, Pedro reined in his mule. Here he turned to look back for the last time at the city of high walls which ascend and descend and enclose the small hill ringed by the river. On their right was the deeply carved bed of the Tagus still veiled in drifting mists and shadows. On their left were hills, rocks, and low scrub, all of which were half-shrouded in a dusty gray. The southern mountains under the early April sky were dimly visible in the distance. Toledo, its neutral tones broken only by shadows cast within its gigantic walls, its roofs dominated by the magnificent towers of its cathedral and its alcazar, was barely visible on the distant horizon. Without comment or command, Pedro took Diego and Lucia from their mules and lowered them to the ground. Catalina, however, asked to be left where she was. The children and their father then sat in the grass beside her litter while their train waited on the road above them.

The river was beautiful in the morning light with the sun glinting off the blue and yellow waters of the stream. Above them, just before the crest of the hill, Pedro and his children could see some crumbling walls. Below them, on the slope of the hill, were live oaks, ilex and olive trees. The olive trees’ delicate, silver leaves parted to reveal clusters of small, black fruit that had refused to be beaten from the branches at harvest. Pedro, who refused to look at the river, sat there bareheaded and motionless as he strained to see the home of his father-in-law on the hill beside the cathedral. He imagined that he could see both the house and its exterior balcony. As they gazed, Pedro, Diego and Lucia were enclosed in their own thoughts of Alonso’s home, the ancient city behind them, and all that they had lost, until Pedro decided that it was time to go. Again, without a word being spoken, for they had all learned to suffer in silence, Pedro placed the children upon their mules. Then, seemingly as an afterthought, he reached into one of the panniers that were slung across the croup of his mule, took out a leather-clad book, and returned to his seat on the hillside. With a final look at Toledo, which was but a smear on the distant horizon, and a last search for the balcony, he began to write.

The first week of April has been filled with such sadness that I have pushed aside my journal and can, now, only cobble it together from memory. It might seem meaningless that I do so. However, I follow the dictates of my teacher who made me believe that who we are and what we experience as a family—and as a people—are important and deserve to be preserved. The dates now seem unimportant. Suffice it to say that this has been the most tragic period of our lives.

He stood up, re-wrapped the journal in its oilskin, and, with a brief prayer rendered to St. Tobit, patron of travelers, said, “We must go.”

To Newer Lands

The plan, as Pedro had outlined in his journal before the family’s departure from Toledo, was for the family to follow the swift-flowing Tagus to Puebla del Mont. Here, they were to ascend the Rio Torcon to the village of Navahermosa. From this point, they were to follow an ancient track across the southward-looking slopes of the Sierra de Guadalupe, to Puerto de San Vicente, Logrosan, and, finally Merida. This track would take them overland through broken, mountainous country whose twisted trees and undergrowth of flowering gorze, blackberry and bilberry sheltered an assortment of wild animals. Here, the woods would be full of animals of every description even if they did not see them. It was this portion of the trip through the mountains of Central Spain that most concerned them. They would be at the mercy of the weather and of the bandits who preyed upon small parties such as theirs. At Merida, they would turn south towards Seville, and from there, they would reach the sea. With luck, and barring any unforeseen circumstances, they would reach the banks of the olive-bordered Guadalquivir River at Seville within three weeks.

Pedro had much on his mind as he let his beast select its own route up the forested trail. He followed the lead mules of their mule train as they slipped and stumbled in mire and muck from melting snow and on the stones and boulders that defined the thorny track. They were following a narrow valley of wood and cork trees with small villages scattered here and there along the way.

* * *

As they passed their days in travel Pedro worried abut what lay ahead. Although there were ventas, or inns, along much of the route, it was impossible to find one that provided both board and lodging. Despite the fact that the inns were filthy, especially the kitchens, which belched thick, black smoke, Pedro and his family continued to stay in them when the opportunity presented itself, for their only other recourse was to set up housekeeping in the fields. The general good appearance of the family often resulted in their being given the best room, but, although they often had the room to themselves, the children’s parents refused to allow them to sleep on the beds, which were little more than lumpy quilts infested with fleas and bedbugs. Instead, and in a guestroom with a chamber pot as their only luxury, they slept on mud floors and on bedding that they carried with them. While the family was accommodated within the inns, however, their muleteers, in the rude manner of the day, slept in the stables on nothing but the panniers and the coverings of their mules all thrown in a heap.

Although the initial portion of their trip was not very difficult, Catalina and Pedro had suffered a catastrophic blow in the deaths of their two children and of their nephew and would have had to be harder than diamonds not to have been brought to their knees. As a wife, aunt, and mother, Catalina had been vitally stricken and was to wear mourning much of her life. As for Pedro, the wound would always be there. But suffering is the essence of being Spanish, and rest a commodity they could ill afford.

For the children, at least, the journey provided distraction. Sleeping each night in a different place and sharing a room and candle with their parents as they had at their home in Carmena, made the trip seem like a grand adventure. That sense of adventure ended when they arrived at the forest.

* * *

Generally, the mountains of Spain have a harsh and lonely appearance. Many are rough, craggy, steeply sloped and forbidding. They have surprisingly few trees and are very sparsely populated. Mercifully, the mountains, or monts, through which the Robledos traveled were small and covered with trees. Although they were also sparsely settled, they served as common pasturage for village cooperatives for the small and infrequent hamlets, which the family came across. However, the Robledos sometimes rode for a whole day without seeing a living creature, except perhaps a cork-stripper with his long-handled hatchet cutting long, oblong sections of bark from the bottom of a tree.

One evening, as it was approaching dark, Pedro and his muletrain spied an inn beside a sluggish creek. They decided to make their lodging there, but the inn was full. The last room had been sold to an odd gentleman, the innkeeper told them, who appeared to be a ‘Romero,’ one of those pilgrims who had gained his name by traveling from the Western Empire (Roman) through the Eastern Empire (Byzantine) on his way to the Holy Land. This man in question, however, was on his way to Santiago de Compostella and he was standing in the courtyard.

The gentleman, a shabby-looking man in what appeared to be penitent’s garb, was standing ankle-deep in mud in his trail-worn sandals. His clothing was most strange. He wore a rude cloak of the coarsest cloth, a short cape, and a flexible hat, and carried a staff to which he had attached a calabaza, or gourd, containing the food he ate. His name, he told them, was Teodore del Torre and he was not actually a pilgrim. “I wear these clothes only to deter thieves on the road,” he said. And his ruse had apparently worked, for he still had all he had come with, which was to say—nothing. Nothing, that is, but a worn book regarding heraldry.

“I’ll be honored to share my room with you,” the strange man said, “and the senora and children can share my bed. It will be a good arrangement,” he said with enthusiasm. “All I ask is that you share the food you’ve brought, for I’ve not come with any.”

The arrangement was not to Pedro’s liking, but he agreed, knowing that Catalina on this night, at least, had to sleep in a bed. The five of them entered the inn and drew up chairs at a rude table that stood near the door. They sat at the table inspecting the hare, which the ventore had placed before them, sniffing at wine stinking of hide and pitch being poured from a ragged goatskin into stone cups, and speaking about this and that. Pedro’s decided to keep the man busy in conversation through the night, leaving the room and bed to Catalina and the children. This appeared to be of no difficulty for Teodore was full of talk. He was planning to submit a petition to become an hidalgo,1 he said, and he was busy designing a coat of arms complete with quartering, crowns and coronets of rank.

“It’s beautiful,” Pedro said of the drawing placed before them expressing more enthusiasm than he felt, “but how does it relate to your name or to your house?”

“The tower, of course, is for Torre,” the man said, “and the mountain is symbolic of my mother’s name which is Montes. This is a little ray of sunshine,” he said, pointing to a yellow slash mark on his drawing, “and the horse is just because I like horses.

“In reality,” he told the family, “my father’s name is Rodriguez, but how does one draw it? The world is full of Rodriguezes,” he said with disdain. “Descendant of Rodrigo! What’s that? I might as well be a Perez, or a Ruiz, or a Martinez . . . a descendant of Pero, Ruy, or Martin . . . one can’t draw those either!”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Pedro said, while holding the drawing up to the candle light and examining the document. “I wouldn’t give that up too quickly, Senor. For example, Martin, or Martinus, derives from Mars or Martis, the Roman god of fertility and war. And, ultimately, Martis derives from the root ‘mar’ which means ‘gleam.’ One could certainly use that. Perhaps you could further search your origins. There’s a Martinez in every wood pile!”

The man looked at him reviewing his red hair and beard and the blue of his eyes in an attempt to determine with whom among their ancestors to place him. Was he Celt, Iberian, Roman or was he one of those Visigoths with their strange un-Spanish names?

“And your name is Robledo, is that right?” the strange man asked with deliberation, a wry smile sliding across his face. “At least that’s what the ventore told me,” he said as though expecting a denial.

“Yes, Robledo. Pedro Robledo,” he responded while looking at Catalina.

“And your father?” the traveler asked, his open mouth revealing acorn stained teeth. “Of what name may we give him?”

“Alejo,” Pedro said, while working at the carcass of their hare with his bare hands.

“Ah. Alejo . . . Alejandro. That’s Greek, you know?”

“Yes,” Pedro responded. “The derivation’s Greek, but we’re Spaniards like yourself.”

“Ro-ble-do,” he said again, drawing out the syllables. “Oak grove, isn’t that what it means? That’s very different from most names and much better than Rodriguez.”

“Thank you,” Pedro responded, knowing that this man now knew more about him than he had cared to share. “Perhaps it’s a place name like Robledo de Chavela or Robledo del Buey.”

“Perhaps,” the man responded while tearing a leg off the rabbit they were eating. “But is it not also like Carvajal, which means ‘oak field,’ or even Zarate, an Arabic word which means essentially the same thing?”

Pedro said nothing, and the man seemed not to notice as he continued with his naming.

“My mother—God rest her soul—said that I should have been a Marquez for my ambitions to become a marquis,” the man continued, his thin lips working but silent. “But my father reminded her that the name may also designate one who works as a servant in house of a marquis. He judged me to be one of the latter,” he said, demonstrating that he could still laugh at himself. “You know, Robledo,” the man went on while requesting another cup of wine. “I would have preferred to have been named Bustillo, or Jaramillo, or Losada, or even Serrano. Preferred to have been named for a pasture for bullocks, a field of orach, an area paved with flagstones, or one who lives on a saw-toothed mountain.”

“Or how about Hinojosa, Vasquez, or Pedroso?” asked Pedro, growing weary of the name game. “A field of fennel, a shepherd, or a place of stones could also be drawn. Those are strong names which conjure up pictures of glory . . . although de hinojos could also refer to kneeling.”

“And you could draw them?” the odd man questioned.

“And you could draw them,” Pedro responded.

Senor Torre and Pedro stood as Catalina excused herself from the table to take the children, Diego and Lucia, and retire to their room. As the man stood there speaking to Catalina who looked pale and worn from their day of travel, Pedro had his first opportunity to really examine him. Pedro made him out to be about 40-years-old, perhaps no older than himself, a serious man of medium stature, earnest but full of pretensions. His pride, he had said, was in being a gentleman and a Catholic, a gentleman as a descendant of those who had re-won the land from the Moors, and a Catholic, in sharp distinction to the New Christians of Moorish blood. He demonstrated the incredible combination of poverty and pride, which, in Pedro’s mind, were so characteristically Castilian. He had nothing, yet he conducted himself with such a comely grace that one unacquainted with him would have taken him for the kinsman of a count. He lived a life of semi-starvation, however, sharing the bread of travelers such as Pedro, probably inhabiting a house of indescribable poverty and squalor and just surviving. Yet here he was with his cloak and his staff, searching for a sword and speaking grandly of his honor and of the estates he would obtain once he became an hidalgo.

After kissing Catalina’s hand and bidding her a good night, the odd man returned to the table in front of the open door that he shared with Pedro. There, they continued their review of Iberian patronymics, place names, and ornamentals from Arechuleta to Zaldivar.

“You’ll notice,” the odd man said, “that neither of us spoke of Herrera or Ferrer, the only two names I’m aware of which designate an occupation.”

“Well there’s Varela, also,” Pedro replied, “even if it is a nickname. It designates a keeper of animals and the rod with which he works.”

“Ah Senor Robledo,” the odd man said, his eyes glazing over from his third cup of wine. “There you have it! If I were to be named Varela, it would be for the varra which I carried as a symbol of my office, or, more importantly, for the rod I take to bed.”

They both laughed at this latter designation, and Pedro reconciled himself to the fact that it was going to be a long night.

* * *

The mule train carrying Pedro, Catalina, and the children rode through a sunlit forest amid fragrant gray shrubs with, here and there, massive boulders draped in luminous foliage. They continued in shadowed silence as they listened for the sounds of horsemen, not knowing who, if anyone, might be pursuing them. However, the only sound they heard was the creak of leather against leather and the heavy breathing of their beasts as they plodded the flinty paths.

After they left the forest, the valley widened and became lush and more fertile. The vale and hillsides, which were awakening from winter’s sleep, were replete with fruit trees now coming to bud. After a day of travel along the ridge of this valley, the mule train crowned the top of a hill in brilliant sunshine, and they could see the village of Punto Llano that lay in a green hollow below them. The houses, which gave the appearance of ancient rocks thrown together under a blazing sun, were shuttered and the doors, over which small family shields had been carved, were locked. Not a soul was to be seen, although the village reeked of tannic acid from cork bark, which was boiling in unattended vats. A lone cow, strangely hobbled by a rope tied to its horns and to one leg, and a small herd of goats wandered in the fields alone, their neck bells ringing in the stillness.

The Robledo party searched the village and could find no one until they came upon an old woman hiding in a hayloft. The woman, whom Pedro referred to as “a woman with a hundred weight of years”—that is a centenarian—told them that the village had been attacked by a group of bandits who had driven off their sheep. Although she was only armed with a thick staff made from the wood of the holly, she had refused to leave with the villagers. The villagers, she told them, were hiding in the hills and would return by nightfall. Although the Robledos were reluctant to leave her there, she insisted they do so, and they hurried away.

Below the village of Punto Llano, the Robledos were overtaken by a small party of two families who, following the same road, were coming along behind them. They were, they said, escaping the village they had left behind and asked to join the Robledos for the trip to Merida. Two of the men in this party carried matchlocks with which to protect themselves. With the safety provided by numbers and with the worn but serviceable arms the party carried, they felt a safe passage would be assured.

From Punto Llano they rode to Logrosan and then down a wide valley, generally following the course of the Rio Ruecas. This route took them through Medellin, formerly the home of Hernando Cortes who had opened the West Indies to colonization. In a bleak landscape commanded by a low hill, they found a crumbling castle with nothing to protect but a string of poor houses fronting a filthy street. Although Cortes had brought the riches of the Aztec Empire to the country of his birth, little of it had remained there, and none of it had stuck to his poor village of Medellin.

From Medellin to Merida was a fine journey of eight days through hills of gray boulders, regal stands of majestic pines, and enormous flocks of partridges, quail, and doves that filled each afternoon’s sky.

* * *

* *

Merida was an ancient city. The Romans, who were later to establish it as the capital of their vast and powerful province of Lusitania, had, in 25 BCE, founded it as Augusta Emerita (Augustus’ Veteran Colony). These were the meritorious veterans of his fifth and tenth legions that had asked to retire from active service and take farms in the area.

The ride was beautiful. Now and then, the travelers saw an ancient noria or hydraulic water wheel with buckets attached. Burros were pulling them around. There were frequent rectangular storage bins of stone or wood, raised off the ground to keep the grain away from rodents. They also found along the trail, shrines and holy places, cowled with a mantle of stone and looking very much like enormous animal burrows. Occasionally, they came across ancient walls and the traces of an ancient Roman road, but, as they neared the city, Roman roads appeared more frequently.

They may have known that in the early history of the church, a young girl, St. Eulalia, the celebrated virgin-martyr of Spain, had, by the use of these roads, trudged into Merida eager for martyrdom. During the Diocletian persecutions (c 304 AD), she had presented herself to the judge, Dacian, and had reproached him for attempting to destroy souls by compelling them to renounce what she considered to be the one true God. Dacian at first tried to flatter and bribe her into withdrawing her words and into observing the edicts. He then threatened her, showing her instruments of torture, and saying, “These you shall escape if you will but touch a little salt and incense with the tip of your finger.” Instead of acceding to his wishes, however, she trampled on the cake that was being laid for the sacrifice, and spat on the judge. Thereupon, two executioners tore at her body with iron hooks, and lighted torches were applied to her wounds. The fire caught her hair and she was burned alive. Legend has it that, following her death, her spirit, as a white dove, flew out of her mouth and soared into heaven.

The Robledo party also saw Roman ruins, including an immense circus formerly seating 30,000 people, and an amphitheater of 14,000 seats. They eventually came upon the Milagros Aqueduct, made of stones shaped and finished so skillfully as to require no mortar. Over 1,000 years old, at the time they saw it, it was doubtlessly good for a thousand more.

The Robledos also saw the 81-arched Roman bridge built across two arms of the wide valley of the Guadiana, a river celebrated for its underground course. The bridge, a half-mile long and the longest ever built in Spain, was repaired by the Visigoths in 686 AD. The members of the mule train knew that these structures were very old, and, although they did not identify them as Roman, they marveled at their construction.

On the morning of 14 April 1577, the mule train set off again with, as the Robledo journal states, “the sound of a distant bell carried by the wind.” They were unaccompanied now but on a road heavy with traffic. Along this road, which was little more than a muddy track scattered with rocks, there were relay stages for the royal mail placed approximately two to four leagues apart. By the use of these stages, the riders of the royal mail could cover up to 30 leagues a day. It was by the use of roads such as these that the king’s letters and special dispatches were carried from Madrid to Seville and to the principal towns of the kingdom. The Robledos made use of the corrals, draw wells and stone troughs of these stage stops to refresh their mules on two occasions, but otherwise stayed at various ventas or slept in makeshift shelters which they built for themselves along the road.

As they neared Almendralejo, they came upon a site recently abandoned by a band of gypsies usually called gitanos bravios, meaning wild or nomadic. The gypsies had camped alongside a stream in the valley below the road the mule train traveled. From the top of the trail, the members of the mule train could see a large wooden wash tub and piggin. They were to find these poorly constructed, their staves of white oak loose and rattly. There were, in addition, a number of other items strewn about which suggested that the encampment had been abandoned with some urgency. Although Pedro told his family that they would not have had anything to fear from these people in terms of their lives, he would have recommended that they remain clear of them because the gypsies were known for stealing and might have made off with their property.

“The gypsies,” Pedro told his family, “entered Europe about 150 years ago and at first posed as pilgrims. The tale they told,” Pedro said, “was that they were from ‘Little Egypt’ and were on a seven-year odyssey to pay for the sins of their forefathers who had turned away the Blessed Virgin with the Child Jesus. Now they’ve dropped this pose and call themselves Greek, but they refuse to go home. That, in fact, is the rub. They don’t have a home, nor do they seem to want one. Their language,” he continued, “is not like ours. It’s said to be Indian, although they’ve apparently lived in Hungary for many years. They’re intelligent and incredibly clever. They learn the language of the people among whom they travel so as to enter their homes, their stores, and their markets. I hate to make generalizations about a people for most often there are as many who don’t fit the label as those who do. However, in this instance, the generalizations are largely true. They make their living by telling fortunes and by predicting what will occur in a person’s life, and then, after they’ve lured you with their psychic ‘gifts,’ they steal from you. Women who’ve gone among them—my mother included—have even had pieces of their dresses cut off.

“When they first entered our country,” he continued, mopping his brow with a well-used linen, “they were given offers of safe conduct and were even provided with alms. However, it wasn’t long before they, and the people with whom they ran, were being paid to stay away.2 It’s unfortunate,” he said with a shrug, “for they have skills as smiths, musicians, and soldiers. However, they’re not to be trusted. No,” he repeated, “best to stay clear of them. We may camp here now that they’re gone, but, should they return for their washtub or these other things, we’ll abandon this camp.”

They took the camp the gypsies had deserted and Catalina, who had begun to brighten in her general demeanor, made use of the tub to disinfect the few items of clothing they had found, some of which fit the children. As she worked at her washtub, she assured herself that every fold and seam was thoroughly scrubbed in the boiling water. Looking over their encampment as the sun slowly sank behind the valley’s western wall, she examined the sky and watched a bird circling at great height in the cloudless heavens. There was something about the evening, perhaps the color of the light as it filtered through the pines, that reminded her of home. She thought back to the bathing time they had been forced to keep secret and to a conversation she had had with Pedro.

_____________