Читать книгу The Rosas Affair - Donald L. Lucero - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

His Lordship the Governor

MEXICO CITY, KINGDOM OF NEW SPAIN,

JANUARY 1637

A footman, acting in place of the duke’s equerry, stood on the path below the garden. “All’s ready, don Luis” he said to the man waiting on the tread of the terrace. “Do you wish for me to bring up the carriage?”

“A moment yet,” replied the governor-applicant, Luis de Rosas, glancing at the landau awaiting him in the courtyard. A moment yet, he thought to himself, one further moment.

The day was bright and clear, crisp winter weather under a brilliant sun. Behind him, the eaves of the two doors leading from a series of palatial halls onto the red-tiled terrace were bright in the morning sun. The eave’s porches of blue tiles and the walls up to the open-eaved roof were decorated with azulejo tiles and chiaroscuro frescos in the Italian design of fronds and foliage spilling from two-handled vases. Before him, his view swept over the walls of the courtyard to a high church and to the huge square façade of the viceregal palace almost transparent in the dazzling light. He could have walked to the palace, but protocol required that on this, his final meeting with the viceroy, he must ride in a carriage.

Rosas, who knew the importance of symbols, bore himself with dignity. He was clad in a rose-colored doublet of rich material worked with rows of silver crescents that sparkled in the sun. In full court dress sans hat, sword, belt, and spurs, his dark, bearded face bordered in a small ruff, he showed only slightly the marks of the pox that had afflicted him as a child. He appeared handsome and rugged with the type of masculine vigor appealing to men. Although sickly in childhood, and suffering all his life with gastric troubles, he showed no outward sign of these ailments or of the tertian fevers with which he was plagued and appeared to be in the peak of health. His medical problems had perhaps impinged on the development of his personality, however. Imbued with a considerable sense of his own importance—although he was, by all accounts, only the son of a merchant—he had been difficult as a child, sullen as a young man, taciturn and stubborn as an adult. Now often rageful and filled with arrogance, his measured bearing on this occasion, would, he felt, show the curious and expectant assembly he was about to meet, that here was a governor possessing presence and energy worthy of their attention.

Rosas knew it was imperative to arrive at the appointed hour. His actions would be observed from the instant his carriage entered the viceregal grounds. And when it did, as the lone occupant of the vehicle, he must appear to be in complete command of the moment. It was early, and, therefore, he waited. He stood at the top of the stairs examining the trappings of his horse, a prancing charger of the finest Spanish breed, waiting impatiently for him to spring onto his back. His horse would, instead, be led behind his carriage from the ducal palace where he had been staying while in negotiation with the viceroy, to the viceregal palace from which he would ride in triumph once he had the cedula (royal decree) confirming his appointment as governor of New Mexico. The preparations for his investiture were a pantheon of symbols, the symbols required of life—and death—in Spanish service. His 15 years of military service as a captain of cuirassiers (cavalry soldiers) in Flanders had taught him the importance of symbols. His attention to these, as well as his keen mind, had assisted him in his rise through the ranks, making him now the confidant and protégé to New Spain’s new viceroy, the Marques de Cadereyta, a knight of Sant’ Iago (St. James). Rosas, as one of the gentlemen in the viceroy’s train, had come with the marques from Spain in 1635. Now, almost two years later—and following the payment of a considerable bribe—his patience in awaiting a lucrative assignment was finally to be rewarded. With a final survey of the duke’s winter garden in which a myriad of rose bushes anticipated a welcome spring, he finished a mental tally of the preparations necessary regarding his horse and carriage.

“You may bring them up now,” he said to the footman.

* * *

The defensive courtyard of the Patio de Armas into which Luis de Rosas rode was flanked on one side by the imposing stables of the viceregal palace containing 30 of New Spain’s finest studs, horses constituting the viceroy’s one obsession. In the stable among these beautiful creatures were the carriages and horses that had brought the members of the audiencia (high court). Opposite the stables, and completing two wings of the patio’s surround, were the offices of the viceroy’s staff. Making a tight circle at the center of the courtyard, Rosas’s carriage made its approach to the palace, arriving square on.

Dismounting before a stone archway in a windowless façade, the governor elect was ushered into the building through its only entrance, a covered loggia or arcade beyond which were broad, open, double-doors, thickly studded and hung with iron. The walls of this gallery were decorated with a rich cloth of raised designs, Italian broccatos (brocades), and painted frescoes whose stiff, geometric patterns reflected European inspiration. A door leading off the entrance hall was held open by two liveried pages, one of whom politely asked Rosas to stand on the threshold of the room’s carved and ornate doorway until he was announced. Waiting at the entrance as he had been asked, Luis stood beneath the doorway’s stone lintel, observing the room’s interior, and dwarfed by its majesty.

Inside the hall, amid a forest of garlanded pillars, palmers, armed with fronds of pine and willow, fanned air that was scented by sprigs of herbs and spices. Rosas admired with great interest the viceroy’s brocade baldachino, a canopy that was erected above the viceroy’s chair. This sign of royalty, the use of which had been denied preceding viceroys, was now being used to accentuate the fact that the viceroy, as the sovereign’s deputy, ruled in New Spain in the king’s stead. As Luis looked at the viceroy’s banner of vermilion on a background of gold damask, he thought that he, too, would have one similarly designed and set out.

The crimson uniforms of viceregal servants, the dazzling short coats of heralds, and the violet jackets of attendants, all cast a regal glow on the walls of the reception hall. The room blazed with the brilliance of their raiments.

Standing beside the viceroy’s chair was a master of ceremonies who briefly glanced in Rosas’s direction before crying out, “Don Luis de Rosas, your Lordship!”

Rosas was ushered into the Salon de Coronas, a great reception hall distinguished by a dado (wainscoting) of azulejo tiles decorated with graceful blue and white designs, and a wooden ceiling, heavily beamed and decorated with radiant crowns. The viceroy, don Lope Diez de Armendariz, Marques de Cadereyta, a self-possessed gentleman with an animated look upon his face, rose from his chair. Twelve other men of honor, all beautifully dressed in their long black robes with ruffled sleeves, joined him in standing to receive Luis de Rosas. Rosas made a motion as to bend his knee.

The viceroy, gentle and pleasant to those with whom he had a close association, reached out with both of his hands and said, “We’ve no need for that, don Luis. Come. Come join us! We’ve been anxiously awaiting your arrival. May I offer you something to drink? A glass of wine perhaps?” He motioned for a servant. “It would be well to have something warm in your belly before meeting with these old men.” The viceroy chuckled at the men standing before him who joined him in his laughter.

“Your health and welfare are all I ask, your Lordship, and if God will maintain these, I shall want for nothing more.”

Elegant in bearing and comely in person, the viceroy was, as the king’s representative, magnificently clothed and jeweled having been exempted from the canon prohibiting Knights of Santiago to wear anything but unadorned rough wool, although he was still obliged to say 15 Mysteries of the Rosary, daily, an imperative which he devotedly observed. He wore the grand, white satin robes of a Knight Commander of the military order of Saint James, his body concealed by the mantle’s cumbrous plaits. With a bright, attractive face and deep-set dark eyes he had a remarkable presence. He introduced Luis de Rosas to each member of the audiencia, with special attention given to its president, Bishop don Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, royal troubleshooter and visitor general. For each member of the high court, he offered a brief resume of titles, lineage, and history in Spanish service. The viceroy then motioned for Rosas to occupy the chair of honor to his right. Rosas moved there, standing between the table and his chair awaiting the viceroy’s signal for all to sit.

The visitor general, don Juan de Palafox, whose chair was directly across from that of the governor-applicant, eyed Luis de Rosas with suspicion. Naturally hot-tempered, impatient and proud—and even, perhaps, a bit contemptuous in his manner—he was, nevertheless, one of the viceroy’s most trusted advisors, and he questioned the selection of this particular individual as New Mexico’s tenth governor. The viceroy, Bishop Palafox knew, was a Spanish grandee who, ruling in place of the king, followed the simple and ancient theory of the “hungry falcon.” This was the practice of placing comparatively unknown men into positions of leadership where their ambitions, plus their reliance upon and gratitude toward the individual who had bestowed the honor, could be counted upon to keep them productive and loyal. It was a method followed by Their Catholic Majesties, Fernando and Isabella, who, upon assuming their thrones, had kept tiny notebooks with the names of individuals they met throughout their travels who might be useful to them. The Catholic sovereigns often solicited the advice of these obscure individuals, ultimately inviting some to join their court. However, the sovereigns’ appointees, like those of the viceroy’s, had not always responded as expected.

And had it not been so with the viceroy’s previous selection of governor of New Mexico? thought the visitor general. Was it not Francisco de Martinez de Baeza about whom the New Mexican priest, Antonio de Ibargaray, had been speaking when he wrote:

From the moment he became governor he has attended only to his own profit, causing grave damage to all these recently converted souls. He has commanded them to weave and paint great quantities of mantas and hangings. Likewise, he has made them seek out and barter for many tanned skins and haul quantities of pinon nuts. As a result, he has now loaded eight carretas with what he has amassed and is taking them and as many men from [New Mexico] to drive them to New Spain, thwarting everything His Majesty has ordered in his royal ordinance.

Stiff charges, Palafox thought. Although loath to have others render such scathing judgments regarding one in royal service, he suspected that much of what Ibargaray had written was true. Martinez has proven to be little more than a drummer, he said to himself. We cannot have a repeat of his misrule. We must do a better job in selecting the new governor.

* * *

Distrusting both the Church and his overseas officers, the king, Philip IV, who had ascended to the throne in 1621, had established in New Spain three royal bureaucracies. Designed as somewhat autonomous but interdependent entities with a complicated system of checks and balances, these branches had ill-defined and overlapping jurisdictional boundaries with little definition as to how they were to share power. The first of these entities was the viceroyalty which wielded authority through a number of provincial governors and which administered in all matters civil and military. The viceroy, therefore, in selecting the governor of New Mexico, did not require the approval of the audiencia, the second of the three entities which constituted the district court of appeals. The third entity, the episcopate, the system of church government by bishops, was charged with ecclesiastical administration. The king knew that litigation among the three resulting from petty jealousies and jurisdictional disputes would check the power of each, while keeping him informed of affairs in the most remote corners of the Spanish empire.

* * *

Kind to his friends, cruel to his enemies, the viceroy was a man of practical skills. To assure that civil and military authority remained in his control, he sought the advice of others but ruled alone. Astute and unusually accurate in his judgment of men and other matters, he had the ultimate responsibility of choosing the new governor, and he wanted Luis de Rosas.

Looking around the room at the men who were gathered there the viceroy placed his right hand on top of Rosas’s left hand and said, “Senores, as you’re aware, don Luis and I have been meeting to work out the various aspects of his contract as governor of New Mexico, and I’m convinced that I have the right man for this assignment. But do not think that we’re here for you merely to ratify my choice. I earnestly seek your advice and counsel in the selection of governor for New Mexico. And I especially request your assistance in the instructions he is to receive relative to the conduct of his office. In the Lord’s name,” he said, as he smiled at those before him, “I now ask for your advice and assistance.”

Don Juan de Palafox, visitor general and president of the audiencia, whose velvet stockings and matching slippers were briefly visible beneath his black cassock, gazed about the room. He knew that it was his responsibility to set the tone for the inquiry, since few of the others would question the viceroy’s choice in the selection of governor. If, therefore, his was the only voice the viceroy and governor-applicant might hear, he had to ask the questions the other members of the audiencia were reluctant to express.

The duo, Rosas and Palafox, observed one another shrewdly, each trying to deduce the thoughts of the other. The pause gave Rosas and the president time to evaluate the gap that lay between them and the audiencia members, time to advise one another as to where their advantage and security lay.

There was a long moment before the president spoke. “I wonder if you truly understand the honor and responsibility being placed upon your shoulders?” His intelligent eyes betraying his wariness of the viceroy’s selection, he added in a contemptuous manner, “I wonder if a man of such meager experience can be truly aware of the difficulties he’ll encounter as governor of such a remote province.” He moved to the front of his chair. “There’s an oft-quoted adage regarding the physical and political climate of New Mexico that expresses it well, don Luis,” he stated, looking directly at the governor applicant. “ ‘Ocho meses de invierno y cuatro de infierno!’ Yes, eight months of winter and four of hell, for New Mexico is but a spare and unproductive land,” he said, “blistering hot in summer and bitterly cold in winter. And although covered in abundant forests, its trees are not subject to forestation, for there are no roads or bridges. Communication is poor, and you’ll be almost totally isolated, cut off from succor or aid.” He paused, and then continued, “The land is colonized by an ignorant and vulgar people, don Luis, a people utterly obsessed with their rights and privileges. A vain-glorious people, bloated with a quite unjustifiable pride in the purity of their blood and in their nobility. You’ll not be welcome among them, for they’re uncourteous to strangers, regarding them with suspicion, if not with outright hostility. They live in mean dwellings, domesticated strong-houses with heavily gated doors reflecting a harsh way of life and built only for defense. These doors will not be opened to you, don Luis, for you’ll not be welcome there,” he repeated. “They’re a tight-knit group,” he continued, “so knotted up through intrigue and intermarriage as to form an intricate web of family relationships impossible to penetrate and difficult to unravel so that it’s impossible to determine where their loyalties lie. It will be of no avail to speak to them regarding their obligations toward royal governors, for even their priests defy proper authority, administering the sacraments to the native converts—and to the faithful as well—in complete disobedience to the holy Council.1 A colony of cousins, they’re a troublesome and obstinate lot, don Luis, full of animus and deception, dedicated to land and family aspirations. They feel they can only count on themselves, and so distant are they from royal authority, that they’ll not easily subject themselves to central control and will not participate in governmental affairs.”

Palafox waited then, waited for his pronouncements to sink in and to be fully appreciated by the governor-applicant who sat there quietly, attentive to the cleric’s words. After a moment, Palafox said, “I apprise you of these things not to discourage you, but to make sure that you’re aware of the extraordinary difficulties you’ll encounter as governor of so remote a province. Do you think you’re ready for this?”

Rosas, who knew the importance of his answers, especially in gaining the approval of those who might be wavering in their support, waited a long and painful moment before replying, his words and tone then calculated to make the greatest impact. After a bit, he said, “I have served on the frontier and have lived the life of a soldier.” Looking at Bishop Palafox straight on and then at each of the men spread about the room, he went on, “And being but a poor soldier, I consider my potential appointment as governor an exceptional honor and will accept it with justifiable pride, and with complete awareness of the burden being placed upon me.”

The viceroy, who had been listening quietly, sat for a long time in silence, surveying the room. His eyes scanned the faces of the members of the audiencia looking for suggestions of approval or disapproval but seeing neither. He asked the president, “Perhaps you’d like to include questions regarding his instructions as part of your inquiry?”

His hands flat before him, Palafox pushed himself to the back of his chair. “Yes, I think that would be helpful,” he responded.

The viceroy’s instructions, previously developed in conjunction with the audiencia, filled seven pages of the book the president now laid before Rosas.

“These,” the president said, “are only the most urgent. If appointed to the position of governor of New Mexico, you will be given more complete details before the departure of your train. Your primary responsibility upon assuming your post would be to re-establish royal command and authority by your personal attention to martial law,” the president said in reference to the New Mexico colonists who seemed to be holding on tenaciously to a medieval dream. “You’ll have to oversee the selection of a new cabildo (town council). At present, some of the councilmen are in confederation with brigands, while other members have intimidated some. We need representatives who are willing to listen to the suggestions we might make for the improvement of our northern kingdom. And we need priests who will allow someone other than their sacred selves to suggest them.

“Equal to that,” the president continued, “is the re-establishment and expedition of Royal justice. In that regard, the governor elect will be required to conduct Martinez’s residencia, the mandatory judicial review of one’s administration. I’m afraid that we’ll find much there that will be of concern to us. And we, of course, look forward to the determinations you might make. Are you equal to these tasks?” the president asked.

Rosas had heard of the passion with which the New Mexican colonists asserted their rights and their independence from royal authority, attitudes exacerbated by the apparent failure of his predecessor, Martinez de Baeza, to assert his control. “I know of these people and of their kabylistic tendency to divide themselves into clans, even into different tribes,” he said, echoing a sentiment previously articulated by the viceroy in reference to the relationship of the early Iberians to the people of the Kabyl tribes. “Some have expressed this tendency as a matter of race, while I see it as an artifact of our ancient times, for they, like us, are shepherds by choice when they’re not soldiers. Their psychology is that of wanderers who will forever fight central authority. Their natural tendency is toward disruption and disunion, which, I believe, can only be contained by the most vigorous, if not the most restrictive, exercise of authority. For no matter their protests to the contrary,” he said, gazing about the room, “New Mexico is not a seigniorial regime in which its lords rule their lands and the tenants on them. New Mexico may be a nation of shepherds and remote beyond compare, a land where sheep are used in place of money, but in one way or another, and with the help of God, I will restore order and authority there and will punish those who are causing difficulty. Your Excellencies may be certain that in anything that involves His Majesty’s service, I shall not be found wanting,” he said gravely, again scanning the faces before him. “I’ll do whatever’s required to clean out the Augean stable you’ve described. And when all is said and done, the colonists will get what they deserve.”2

These were the right words and the members of the audiencia smiled and nodded their assent. The bishop, who could wield a sword with both hands, determined to give his vote to the avowedly anti-clerical Rosas, but also to keep his eye on him. Looking across the table with solemnity, his long face, sharp nose, and high forehead, reflecting his gentle birth, he spoke politely and with sentiment, saying, “I have every faith that you’ll do your work well.” He then looked at the viceroy, nodded his head in agreement at the viceroy’s choice, and speaking to Rosas directly, said, “You may now wear a hat.”

The members of the audiencia stood and a great silence invaded the hall. Placed before the viceroy were the symbols of Rosas’s office, his sword, helmet, and spurs. President and Bishop Juan de Palafox, who had risen from his chair with the others, walked around the table and with much gravity grasped Rosas’s sword and belt and assisted the new governor in putting them on. Kneeling before Rosas, a page affixed the governor’s long silver spurs to his high riding boots, while the governor, assisted by President Juan de Palafox, placed a small hat of crushed velvet upon his head.

After this was accomplished, the viceroy said, “Senores y Caballeros, Gentlemen, I give you don Luis de Rosas, military commander, captain-general, governor of New Mexico!”

Rosas knelt at the feet of the viceroy who had remained seated throughout his investiture. The governor’s induction completed, Rosas removed his bonnet and laid it courteously in the viceroy’s hands signifying, thereby, that he was the king’s man. The viceroy accepted his hat and placed it aside. Then, putting his hands in the viceroy’s palms, and swearing to defend his lord faithfully and to protect the New Mexican kingdom from its enemies, Luis de Rosas waited for what seemed an eternity for the viceroy’s response to his gesture of vassalage.

“You’ll meet with Fray Tomas Manso, procurador-general of the province, who is responsible for the missionary supply service and will proceed as he advises you,” the viceroy said to Rosas. And then to the members of the audiencia who had remained on their feet, the viceroy said, “We will honor the governor’s request to dispense with the festivities and entertainments this occasion would ordinarily require. Governor don Luis de Rosas has asked only that we share a glass of wine with him and that he be allowed to proceed with arrangements for going to his new home.” Finally releasing Rosas from his grasp, he stood, raised the governor to his feet, and embraced him most graciously and affectionately. Wine was poured for all present. Several toasts were offered.

“We wish to hear of your progress as you go along your way until you are beyond sight and sound,” the viceroy said. “Please make sure that we do so. Go with God, my dear Rosas!” He then gave the governor the kiss of peace and dismissed him from his chambers.

Several of the men with whom Luis had met followed the new governor through the heavy oaken doors of the viceregal palace and into the courtyard, ablaze in winter light. These so-called hombres ricos (the rich and powerful moguls), trim and haughty gentlemen carrying fluttering banners and Toledo blades, mounted horses that were now being brought to them. Their horses were caparisoned with silver-studded saddles, silver horseshoes, and bridles.

The governor’s friend, the duque de Segorbe, at whose home Rosas had been staying while engaged in his many meetings with the viceroy, sprang from his own horse and held the governor’s stirrup so that he could mount. Luis hesitated for a moment, his left hand grasping the pommel of his saddle, looking down at the gentleman who knelt at his feet. Theirs was friendship of convenience only, with little pretense of affection or loyalty, and the duke, Rosas knew, would throw him to the wolves if it provided the duke with an advantage. But that was all right, Luis thought, for I would do the same. However, this incredible gesture of humility, so uncharacteristic and unexpected of a royal knight, pleased him immensely. He had arrived in New Spain without position or prospects, and was now, with the duke’s assistance, to be the ninth individual to serve as governor of New Mexico. He thanked the duke for his gesture, truly gratified that Segorbe had sought to put the stamp of importance on the event, for Rosas had only Segorbe with whom to share the proud moment. There was no one else.

Rosas lifted himself into his saddle glittering with gold gaud interspersed with red. The governor’s boots were now adorned with the silver spurs, and he was girdled with a sword, its pommel of acacia wood wrapped in silver. On his head he wore the hat he had retrieved from the viceroy. Made by hand with the flora and fauna of his adobe kingdom sewed in with gold embroidery, it was one of the most important symbols of his office. He wielded a rod of holly in place of his lance as he and his small retinue clattered out of the courtyard.

* * *

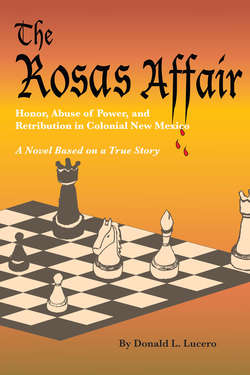

On their return from the Zocalo, the central plaza around which the governor and the other members of his slight entourage had briefly ridden, Segorbe and Rosas retired to the duke’s study where they sat before his blazing fireplace. The duke smiled at the fledgling governor, a man with whom he had fought in Flanders and with whom he was now engaged in the mercantile business in New Spain. The new governor, the duke knew, was in every way excessive, headstrong, and ambitious, one of the lowest grade, who, because of his successes in battle while in Flanders, had grown so proud and arrogant that he had become insufferable to his men. Glorying in the spectacle of battle where the prize goes to the bold and the brave, he had become coarse and dogmatic, lacking any of the refinements he had pretended to when he had presented himself at the viceregal palace. He was, nevertheless, the pawn in the duke’s opening move or gambito in the duke’s attempt to gain economic advantage in Spain’s most remote Northern Kingdom. The viceroy, who had waited a long time before replacing Martinez as governor of New Mexico, had found in Luis de Rosas a ruthless soldier who would again assert civil and military control in the Northern Kingdom. This pawn, Rosas, the duke thought to himself, has reached the eighth row on the chessboard without being captured by a member of any opposing army we fought. He deserves this promotion, if not a “queening,” then a governorship. Self-styled as a grandmaster in the game of political chess, Rosas might, as the king’s knight’s pawn, eventually have to be sacrificed, as Martinez de Baeza had been, in the crown’s struggles with New Mexico’s recalcitrant colonists and priests. Segorbe’s gloomy prediction for Rosas was that he would not long endure among the New Mexican settlers. But while he survives, the duke thought, the governor’s single-mindedness and strength of purpose, uncluttered by peripheral issues, can be counted upon to make both the governor and myself a sizeable fortune.

“Martinez is as good as dead,” the duke said to Luis while grasping and ringing the small bell that sat on his table. “You may, in conducting his residencia, appear kind and benevolent while taking whatever you damn well please.”

“I think I can do that,” Rosas said with a broad grin. “I think I feel benevolence coming on. Almost like a seizure,” he said with a satisfied smile. “Or perhaps it’s flatulence, I don’t know. I get those two mixed up,” he added laughingly, as he requested another glass of wine from the servant who had arrived at the duke’s summons.

The two men waited for the servant to leave before continuing their conversation regarding New Mexico. After a time the duke said in a more earnest tone, “You know, don Luis, the power is in your hands. Martinez will do whatever’s necessary to save his worthless neck, pay whatever’s required for a favorable report. He’s as good as dead,” Segorbe repeated. “And that being true, you may take the best animal in his herd.” A short pause, then he went on, “The Indians of New Mexico are required to pay tribute and Martinez knows the business of maize and mantas and skins. He can be made to pass the business on to you. That’s the way it is,” he said emphatically. “You’re to be paid two thousand pesos annually for your service as governor of New Mexico, hardly enough to get you there and to support you in anything befitting your position, and certainly less than the eight thousand you paid to secure the post. And, by the way,” he added, pointing a long bony finger at the new governor, “don’t forget that you owe me four thousand of that. We have to make a profit on our investment. And both the crown and the viceroy are prepared to tolerate our business enterprises so long as the sounds of weeping and wailing and the gnashing of teeth do not reach their ears. The decade of exemption for the Pueblos has passed,” he added, “and a workforce in New Mexico, both unpaid and forced, is readily available. Your plan should be as we sketched it: to divide and conquer. It shouldn’t be difficult, Luis. The colonists and Indians there carry either a candle or a club. Your goal should be as we outlined it, to castrate the colonists while separating both the colonists and the Indians from their priests. I look forward to receiving your mantas and skins when your carretas return with the wagon train,” he said again, smiling, while reaching for a bag that he had placed beneath the table and rising to his feet. “I give you this as a token of our contract.” The duke handed the governor a velvet bag in which a chess set had been placed. “To New Mexico!” he said as he raised his glass in a toast. “May it reward us greatly!”

2

Fray Tomas Manso and the Service of Missionary Supply

The governor dismounted from his horse in the shadow of the convento and proceeded to its gate, slapping at his thigh with the short whip he carried in his hand. Reaching the porteria (convento gate) of the walled enclosure, he tapped on it lightly with the butt of his crop, then more soundly, finally beating on its wooden staves with his closed fist. “Goddamn it!” he yelled, as the door opened to reveal a curious face. “Were you waiting for Father Francis’s steward to announce my arrival?” he asked repeating a proverb often used in Castile. “You did expect me, did you not?” he shouted, as he rudely brushed by the portero (gatekeeper) who had opened the door.

“Yes, your Lordship,” the servant responded meekly. “The fathers are at prayer. The walls are thick, your Lordship, and the cells are beyond the walls of the courtyard so that I did not hear you,” he explained apologetically with smiling scrapes and bows as he ushered the governor into an inner chamber. “Fray Manso will be with you in a moment.”

“In a moment,” the governor muttered to himself. “Tell him that I’m waiting!” he said emphatically, slapping at his thigh.

Procurator-General Fray Tomas Manso, who was responsible for purchasing and stockpiling missionary supplies for the northern kingdom, finally appeared in the doorway, his eyes sharp, discerning. Having never experienced the manner in which he had been summoned, the well-respected friar stood there surveying the man who had demanded his presence saying, finally, and with ill-disguised annoyance, “Please come with me.”

Fray Manso led the governor into the convento’s interior patio and then to a storeroom whose lock he opened with a large key kept on a chain that was hanging around his neck. Flecks of dust floated in the sunlight as he opened the storeroom’s huge oaken doors. Two 200-pound bronze bells partially blocked the entrance. Working their way around the bells, Fray Manso and the governor stepped inside.

Arrayed alongside one of the storeroom’s inner walls were oil paintings of saints in gilded frames and several huge illuminated choir books which Fray Manso said contained introits and antiphonies for various saints’ days. “These piles over here,” Manso said of the mounds heaped against the opposite wall, “contain forty pairs of sandals; twelve large latches for church doors with their locks, keys, and ring staples; and one-hundred and twenty Sevillian locks with their keys for the cells, or private rooms for my brethren. Those other piles,” he said, pointing to the back wall, “contain replacement parts, the supplies required for rebuilding our wagons, such as, spare axels, extra spokes, extra iron tires, and the tools required for their construction. And there is the equipment required for building a church, axes, adzes, small hand saws, long two-man saws, chisels, augers and planes, as well as the spikes, nails, pins, and tacks required to hold it together.”

“What’s in these?” Rosas asked, as he rapped on one of the many barrels arrayed about the room.

“The dry casks contain raisins, almonds, sugar, saffron, pepper, and cinnamon,” responded Fray Manso, “while the wet casks are filled with olive oil, peach and quince preserves, syrup, honey, wine, and vinegar. And these, of course,” he said of the damask vestments hanging from pegs on the wall, “are required by my brothers in their ministries. The colors alone should dazzle the natives,” he said with a satisfied smile.

They walked about the room with Fray Manso dutifully showing and explaining the need for each object. The governor, largely silent but in deep thought, tested the heft of the metal goods provided, lifting one of the lighter ones above his head and then dropping it onto its pile.

“And how many wagons will we have?” the governor questioned.

“We’ll have thirty-two wagons traveling in two groups of sixteen, two of the wagons allocated for your belongings.”

“I’ll need four wagons in addition to those I have,” the governor said.

“That’s impossible,” Fray Manso answered abruptly, his patrician face and lined forehead now betraying his anger. “What you see here is the result of eighteen months of work,” said the priest, brushing at the pale fringe of his hair. “We’re the only regularly scheduled freight and mail service to the Northern Kingdom, and we only go every three years. I’m sure that you would not ask that the friars be denied food or clothing merely to accommodate you,” he added in a haughty manner, while kicking at one of the large bells with a sandaled foot. “We can spare no more than two wagons,” he stated. “Perhaps you can purchase some of the things you’ll need from Governor Martinez. He may be happy to leave his possessions there so as to give him more room for the hides, salt, paintings, and pinon nuts he seeks to bring back.”

“I’ll not have cast-offs in my home,” the governor said, “nor will I wear bits and pieces or hand-me-downs. You must remember that I have a distinguished station to uphold or imperial influence will suffer. Whose wagons are these anyway?” he asked angrily.

“Well, it’s not all that easy to say,” Manso responded while shaking his head. “Initially, the cost of each wagon and its sixteen mules was paid for by the crown. To be exact, three hundred seventy-four pesos and four tomines. But we’re to assume the upkeep of the wagons and the replacement of mules, so is it a shared responsibility and ownership?” he asked with a shrug. “I don’t know. But as far as I’m concerned, they’re ours. They belong to the Custody.”

“Well, I don’t really give a shit who they belong to as long as I get my share,” responded the governor in kind. “I must have at least three of your wagons and where you put these other things is of no concern to me. My equipment and gear will be on your carts when we leave,” the governor said as they exited the storeroom.

Fray Manso placed the padlock in its hasp and did not respond, walking quickly through the patio and then down the hallway with the governor, leading him to the exit.

3

Francisco Gomez and the Baggage Train

The fardage, or baggage train, was composed of beasts and wooden carts, some of which contained the dishes, bedding, tapestries, and other possessions of the governor’s household. It was spread out in the courtyard of the Convento Grande, the Principal House of the Holy Gospel, where Fray Tomas Manso was inspecting it.

The wagons—heavy, four-wheeled, iron-tired freight wagons drawn by teams of sixteen mules—were each capable of hauling two tons of equipment and merchandise. Inspecting the train with Fray Manso was Captain Francisco Gomez, a heavy-set individual with red hair, beard, and a flowing mustache, all streaked with gray, who, with a detachment of fourteen soldiers, had been sent from New Mexico to escort the governor to his adobe kingdom. A handsome man with light-colored eyes and a wound mark above his right eyebrow, Gomez was a natural leader and confidently assumed his responsibility for the train.

“He has everything on his carts, even, I suspect, stones for his mangonel,” remarked Fray Manso shaking his head in disgust.

Before them, were seven wagons bearing the governor’s personal things—his bed furnishings, garments, books and documents—tied up in hide-bound sacks or stored in chests. His kitchen, appointed with numerous pots and pans, was slung beneath one of his wagons. Two additional carts, which the governor had placed behind his personal wagon, contained articles of foodstuff and wine for the lengthy journey. Then came several canvas-topped carts burdened with baskets and chests containing carpets and wall hangings for the governor’s lodging. Twelve pack mules bearing the governor’s table service as well as other household items were also burdened with a heavy oak table and its chairs, and a banquet service of twelve silver dishes and cups. Guards attended by several alferezes (ensigns) bearing the governor’s armor and tack brought up the rear.

Gomez, a Portuguese soldier formerly in service to the Onates, and one who gave his first allegiance to the king’s man whoever he was, said, “I’m sure that he’ll become a more reasonable traveler as we go along.”

“You think so?” Fray Manso asked with a smile.

“We can only hope,” answered the 61-year old Gomez who had seen it all.

* * *

With the sun rising over their right shoulders, and with prayers rendered to God for a safe journey, the members of the wagon train set out. They rode aboard freight wagons, and astride saddle mules and horses, their faces set northward toward the mining town of Zacatecas. The whip-cracking muleteers on the train’s 36 heavy, groaning wagons damned their mule teams and their misfortune at drawing this assignment. Assorted retainers, an extra team of 16 mules for each wagon, and meat on the hoof, brought up the rear.

Blas de Miranda, who, like Francisco Gomez, had been a member of several previous wagon escorts, was asked by Gomez to divide the train into smaller and more manageable units: two squadrons of eighteen wagons each, broken down into four nine-wagon divisions, with each squadron under the command of a wagon master. With the assistance of Nicolas Ortiz, who had also been a member of previous wagon trains, Miranda now made that division. The two lead wagons rumbling side-by-side flew banners displaying the governor’s coat of arms, their teams distinctively caparisoned and wearing bells on their harnesses. The two young wagon masters, Miranda and Ortiz, rode beside their lead wagons, while Gomez, as mayordomo or conductor of the train, trailed behind.

“That man—Gomez?” Rosas asked of one of his aides, as they rode beside the governor’s lead wagons. “What do you know of him?”

“Little,” his aide responded. “Only that he’s an encomendero, or ‘estate holder,’ one of the kingdom’s most prominent soldiers, and the strongest defender of royal authority as vested in the governor. I think that he has no love for Governor Martinez,” his aide continued, “yet Martinez can count on Gomez’s loyalty until the day he leaves office, for that, they say, is the manner of the man.” His aide, who was attending to his horse that had stumbled on uneven ground, continued, “Some say that he’s an alborayco, the son or grandson of a Jew from Portugal forcibly converted to Christianity.”

“And you know little of him, is that right?” the governor laughed. “With what you’ve told me I could either give him the kiss of peace or send him to the gallows. Tell him that when we camp at Queretaro, I’d like him to take council with me.”

“Yes, your Lordship,” his aide answered as he slowed his horse’s pace to drop in with the rear guard. “I’ll tell him!” he shouted.

* * *

At Queretaro, the first important station on their way north, they made their camp. Ringed about with mountains, Queretaro lay in a wide rolling plain, open during the day to the winter sun. On the move, with just a night’s camp expected, the governor had only the canvas of his field tent erected within which he now sat, a velvet robe draped across his shoulders against the evening’s chill. His servants entered and unfolded a day bed and draped it with several portable and lightweight sarapes del campo. These utilitarian camp blankets of natural dark-colored wool, striped with small bands of red, provided the only color in the canvas room. The servants then brought in a small writing desk, candles, a firebox full of radiant coals, wine and glasses. Also among their kitchen paraphernalia, were two large bowls, several spoons, a ladle, a kettle of soup and a tureen into which to pour it. The servants, having made things inviting with furnishings and food, removed themselves, pulling the flap of the tent closed behind them.1

In the last of twilight, Francisco Gomez watched the fog that back-dropped the encampment, hesitating at the entrance of the field tent before calling out and then lifting the flap. “Your Lordship,” Gomez said in a verbal salute, “you requested I meet with you?”

“Don Francisco,” the governor responded appearing at the door like a cowled monk with his robe draped about his shoulders. “Please, please, come in and add your warmth to my poor household,” he said as he sat on one of the large cushions arranged about the canvas room. “And you may dispense with formal titles while we’re on the road,” he added as he beckoned Gomez to take a seat. “You may call me don Luis.”

“I wouldn’t be comfortable addressing you in that manner, your Lordship,” Gomez responded, speaking politely, but without excessive deference.

“Governor, then,” Rosas responded with some annoyance. “You may call me governor.”

Gomez declined the bison robe offered him for warmth and waited for the governor to continue, thinking that the manner in which Rosas was looking at him suggested that he was disturbed about something. Gomez looked directly at the governor, trying to discern in Rosas’s countenance the nature of his annoyance, turning over in his mind the many possibilities. He waited.

“I understand from Fray Manso that we’ll be at least four months on the road, and I mean to make use of every moment of that time to learn the secrets of New Mexico,” the governor said.

“And how may I be of service to you?” Gomez asked.

“I’ve been told that you’re the most outstanding military official in the kingdom,” Rosas said, further drawing his robe about his shoulders. “I don’t say this to flatter you, but to tell you that I expect much from you—as one soldier to another.”

“I’ll do whatever I can to assist you, your Lordship—pardon me,” Gomez laughed, “Governor.”

“Soup?”

“Yes, please. May I serve it?” Gomez asked.

“This I can do myself,” Rosas responded, as he ladled the contents of the tureen into two bowls and placed them side by side on the small writing desk before continuing. “This should compare favorably to your usual fare,” the governor exclaimed, knowing that Gomez’s typical food was the same as that enjoyed by his men: a scanty repast of one meal a day consisting of a small piece of meat, red chile, beans, and tortillas (maize cakes), with a cup of chocolate and a piece of bread in the late evening. “I have much to ask,” Rosas continued, “but first, tell me a little about yourself. I like to know with whom I’m dining.”

Gomez waited a long moment before responding. Clearly uncomfortable in speaking about himself, he stroked his graying mustache with the tips of his fingers saying, finally, “The facts are few, Governor. My origins are in Portugal. In Coina, five leagues from Lisbon. You may know it.”

“Lisbon, yes, but not Coina,” the governor responded. “A port city, I assume?”

“On the interior a bit,” Gomez responded, “with access to the sea like Lisbon, but much smaller, of course.” He waited before continuing, looking about the tent, choosing his words carefully as he said. “I’m the son of Manuel Gomez and Ana Vicente, both of whom died when I was a child. I was raised and schooled by my older brother, Fray Alvaro Gomez, a Franciscan in the Convento Grande in Lisbon and Commissary of the Holy Office. When I was thirteen,” he went on, speaking deliberately “I passed into the service of don Alonso de Onate at the Court of Madrid. He was there pleading the case of his brother, don Juan de Onate, regarding don Juan’s New Mexico contract. He brought me with him to Mexico when he returned there.”

“And when was that?” Rosas asked politely, as the two dipped into their soup.

“It was in sixteen four or five,” Gomez responded with uncertainty, “a year before I joined don Juan in New Mexico.

“Juan de Onate? New Mexico’s first governor?” Rosas asked rhetorically.

“Yes, New Mexico’s adelantado,” Gomez responded regarding the honorific office Onate had held. “I first served with don Juan, and then with Governor Felipe de Sotelo, whom I also escorted to New Mexico. I’ve been in service to the office of the governor since my arrival there.”

“As an encomendero?” Rosas asked. “As the recipient of an encomienda, one sworn to answer the governor’s call to arms when requested?”

“Yes, one of thirty-five in the colony,” Gomez responded. “My encomienda, good for three lifetimes in succession,2 is at the pueblo of the Pecos,” Gomez went on, giving no hint of the breadth of his extensive holdings which included New Mexico’s best-watered lands, tribute from its most prosperous Indian villages, and access to trade.

“The entire pueblo?” the governor asked incredulously. “Was the entire pueblo given to you?”

“Not the use of native land or labor, Governor, but the collection of tribute as personal income. I am allowed to collect tribute from the entire pueblo of Pecos, except for twenty-four houses which are held by the Maese de campo, my friend, Pedro Lucero de Godoy. Also from two and a half parts of the pueblo of Taos, half of the Hopi pueblo of Shongopovi, half of the pueblo of Acoma except for twenty houses, half of the pueblo of Abo,” he continued, “and the entire pueblo of Tesuque, although I receive services from the people there in lieu of tribute.” 3

The governor rubbed his hands together, looked at Gomez, raised his eyebrows, and blew between pursed lips. “And what do the other thirty-four have” he asked of the remaining encomenderos, shaking his head in disbelief.

“I won’t attempt to justify the amount of tribute I’ve been allotted, your Lordship,” Gomez said, flushing slightly and reverting to the governor’s more formal title, “except to say that I’ve been deeply honored to have carried out many commissions for the governors under whom I’ve served. My services have been very generously rewarded, far in excess of what I deserve. There are, however, over forty thousand Christianized Indians living in forty-three pueblos in New Mexico, and the range of our responsibilities is enormous.”

“And the tribute consists of . . . ?”

“Maize and a manta or animal skin, collected twice a year,” Gomez responded. “The manta is a piece of cotton cloth six palms square, reckoned in price at six reales. A buckskin, bison hide, or a light or heavy elk skin of the same value, may be substituted for a manta,” Gomez said, “with cloth and skins collected in May and a fanega of corn in October after the harvest.” 4

“And what do the Indians get for all of this?” Rosas asked.

“It’s difficult to say, Governor,” Gomez responded pensively. “As vassals of the crown they’re required to pay tribute. And the king has granted us encomiendas for our pledge to defend the land at our own expense. Those of us who have been designated as encomenderos are to maintain arms and horses, live in Santa Fe, and respond to the governor’s call to arms at a moment’s notice. We ride escort, serve as guards, and command levies from colonists and Indian auxiliaries in the colony’s defense. We like to think we make the kingdom a safer place to live, but in truth, your Lordship, I think the Indians get little from what we offer. We defend them from the vaqueros as best we can, but there are few of us, many of them, and millions of miles to cover. We assure the safety of the friars so that the Pueblos 5 are instructed in Christianity and in the ways of civilization, but, really, the Indians want little of that. They do not get much of what they truly want or need from Spanish authority.”

“Are all the pueblos allotted?” Rosas asked. “My instructions say only that the crown has reserved the right to collect tribute from principal towns and seaports, and I know there are none of the latter there.”

“Tribute from the native settlements has been conceded by the crown to the colonists themselves. Approximately sixty so-called ‘units of ‘entrustment’ have been allotted during the past forty years,” Gomez explained.

“There was a time, Governor, when the number of pueblos may have exceeded the one hundred and thirty-four named by Onate. These were small and large villages containing from twenty to seven hundred and fifty rooms, some with defensive walls such as at Pecos. But the Pueblos were constantly on the move,” he explained, “uniting and then dispersing like bees in a hive. Whole tribes have disappeared, extinguished by warfare and by assimilation, some of the latter forced on them by us. In the fifty years from the initiation of the colonization by Onate to your administration, the number of pueblos has been reduced by two-thirds, so that now there are fewer than fifty of them left. Several of these pueblos are unassigned, but the fact that they have not been allotted undoubtedly means that they have little to offer in the way of tribute. Still, Governor, they’re there. And they may be awarded by you to whomever you wish so long as your awards do not compromise the awards of your predecessors,” he concluded, warning the governor by his words that he knew the authority under which he held his claims.

The governor looked at Gomez in deliberation, saying finally, “There’s much to consider regarding these encomiendas, much to consider. Your thoughts and the information you’ve provided have been of considerable assistance to me. I’d like these discussions regarding New Mexico to continue as we go along our way.” He waited a long moment before continuing, saying finally, “But please, finish your soup. Take the rest of it. I need something more. Something to deal with this god-damned constipation,” he added while rubbing his distended stomach. “Would you like some more?” he asked, regarding the soup.

“No, thank you, Governor.”

“When your work allows,” Rosas continued, “I’d like you to dine with me.”

“When my work allows,” Gomez responded. Taking the governor’s words and tone as a cue for his dismissal, he rose from his cushion, excused himself, and moved toward the entrance where he said. “You might have one of your servants find some acacia, agave or algerita, your Lordship. All of them are good for constipation. If they can’t identity these plants,” he added, “tell them to ask one of my men. Have them make a tea of it,” he added as he left the tent.

4

On the Trail

ZACATECAS. THREE WEEKS LATER

What’s that ahead—Zacatecas?” asked the governor regarding the hump-backed mountain somewhat resembling a hog bladder which loomed on the northern horizon.

“The home of the Onates,” Francisco Gomez responded, pointing to the promontory of La Bufa crowned by bare greenish rock. “Its mines, perhaps the best ever found in the Americas, helped to finance the settlement of your New Mexican Kingdom.” He brought his horse up so that he was riding beside the governor. “There was a time, Governor, not so long ago,” he continued, “when we could not have approached this villa without arms. The Chichimecas, or the dirty, uncivilized dogs, as we were prone to call them, were incredibly fierce warriors—cannibals even—who inhabited the deserts and sierras of this region just a short time ago. They’re largely gone now,” Gomez said, “killed or shipped off to the docks at Vera Cruz or to mines throughout the kingdom, men who’ve been changed from lions into hens. It’s too bad,” he said in rueful admiration. “They had much to admire, for they possessed courage inferior to no one, and before our arrival, they never knew slavery or servitude. We may see a few of those remaining in the market place or along the road, their bodies clothed now, and their voices stilled. We may see them, but they will not be the people they once were, for we took what they had and left them a sad and broken people with no interest in, or aptitude for, village life. They’re neither civilized nor productive members of the Spanish community,” he said as he reigned up at the train’s approach to an obvious fork in the road. “Do you wish to enter the city?” he asked of the governor. “Your host here will be the local superior or father guardian at the Parroquia de San Francisco de Zacatecas. The convento itself, however, is in open country at some distance from the town, so that unless you wish to do so, we’re not required to enter the city to visit the parroquia which is just down this road.”

“I don’t think it will be necessary to go into the city and I’ll take advantage of the guardian’s generosity as long as I don’t have to do the stations,” Rosas laughed, registering his dislike for visiting churches. We’ll take advantage of the fathers’ hospitality, but I’d like to be on our way again as soon as possible.”

“As you wish, Governor.”

SANTA BARBARA

Leaving the Custody of Zacatecas where its father guardian had sought to instruct Luis de Rosas about a governor’s proper relationship to the Church, the party passed through Sombrerete and Durango. Trudging ever northward, the caravan finally crossed the Nazas, a fast, wide, deep, sediment-laden river, the color of rust, which raced through a broad, fertile valley below Santa Barbara. This was the jumping-off point for the New Mexican Kingdom. It was from this mining town, founded among the Conchos Indians by Rodrigo del Rio de Losa, that the most important New Mexican expeditions had embarked.

“The expeditions of Agustin Rodriguez and Francisco Sanchez Chamuscado, Bernardino Beltran and Antonio de Espejo left from this town, and Juan de Onate’s second inspection was conducted here,” Gomez said. “It was here, too, that his retreating colonists, when deserting the kingdom only four years later, sought shelter in the arms of Nueva Vizcayan authorities. This is where it all came apart for don Juan,” Gomez added, “here in these mesquite groves, among these naked and poor Indians. I pray that, in your quest for an orderly and decent life in the New Mexican Kingdom, that you’ll be more successful.”

“Is there anything to be learned from all of this?” The governor asked.

“Only that New Mexico presents an incredible challenge for one who would attempt to govern it,” Gomez said, “for New Mexico is not a castle, but an island, Governor, an island whose very isolation is seen by its eight hundred Spanish colonists as being to their advantage. Its governance requires maintaining a precarious balance between the wishes and needs of the clergy, the settlers, the Pueblo and Plains Indians, and Spanish authority, with each having incredible determination and will as deeply rooted in them as in any people. I would not presume to tell you how to conduct your office,” Gomez continued, “but if one is to be successful in governing New Mexico, the needs and desires of the three estates must be kept in perfect balance with the promises and difficulties presented by the Indians. Neither Onate nor anyone else has been successful in achieving that balance.”

“And you, Gomez, do you speak of yourself when you speak of the New Mexican character?”

“Yes, I guess I do,” Gomez responded thoughtfully, “for I am, like you, a descendant of the Iberians, fearless soldiers who fought courageously but never learned to hold their shields together in combat. We learned, though, those of us from Spain and from Portugal, to fight together. Learned to hold our shields together in an impenetrable phalanx and have thus become among the greatest soldiers on earth. What we have not learned is how to live or work together as a people. And our independence and separatism, our stubborn refusal to be welded into a uniform dominion, are, perhaps, both our strength and our weakness. But our shortcomings, or what others see as our shortcomings, have made us who we are, and the qualities that are ridiculed as our faults are really the bases of our superiority. I was not a first colonist, Governor, not one of Onate’s soldiers of fifteen ninety-eight or sixteen hundred, but I am one of them. So, yes, in terms of tenacity and will and pride, I am one with the New Mexico colonists and they are both the root of my successes as well as my failures.”

Gomez was quiet for a long time, seemingly contemplating it all, saying finally, “This is the last measure of civilization we’ll find before entering the wilderness. The country above Santa Barbara is referred to as ‘The Beyond,’ and you’ll find little there. If you wish to correspond with anyone in the city of Mexico, or elsewhere, this will likely be your last opportunity.”

* * *

Governor Luis de Rosas looked over Santa Barbara’s extensive lands of mesquite and grass plains, a land bathed in the winter colors of sienna, gold, and burnt umber, viewing the many arroyos and verdant valleys of the foothills region leading to the Rio Conchos. He took his final opportunity to communicate with his business partner, the duque de Segorbe, and, also, as required, with his “Most Illustrious Sir,” and with the audiencia, sending back with a returning caravan, his final notes. “Before me,” he wrote to the viceroy, “lies a desolate land without convenience or refuge, offering every means of misfortune and peril. We will, nevertheless, keep our pace of ten or fifteen leagues a day and find our provisions along the way.” And to the duke he wrote: “I see little of promise here, even my digestive difficulties have worsened. But perhaps things will improve as we go north.”

DEL PASO

Trudging through sand dunes, the caravan continued northward along a route as ragged as the bed of a stream. Above La Toma del Rio del Norte (where Juan de Onate had, in 1598, first entered the new land) the caravan crossed the watercourse at a gorge the river had carved between two oddly shaped hills. The pass, referred to by the Indians as a “gateway” or “mountain gap” (the Spanish equivalent of which was “Los Puertos”), was, for the traveler of the period, the gateway north. Beyond “the pass,” or “del paso,” the train encountered a cascade of rapids. Beside the brown torrent were grassy banks in narrow strips, which at various intervals, spread out into small meadows with dense stands of emerald-hued willows growing along their edges. On either side of the river were rolling stony hummocks and higher knolls of naked earth.

* * *

In the opening days of the New Mexican spring, the train moved up the east side of the Rio Grande Valley, its route devised so as to avoid soft and sandy ground and steep inclines. Lofty mountain ranges were strewn here and there both to the east and to the west of the river, with barren plains waiting just beyond the river’s banks. The days were hot and a cloud of dust billowed behind their many beasts as the men of the wagon train rode along.

The river, offering appealing trailside marshes, coves, and pools, was a corridor for the millions of migratory birds the travelers saw as the birds made their annual relentless passage northward, moving from winter food in the south to their northern breeding grounds. Following the birds, the members of the caravan pointed the noses of their mounts northward and continued their journey.

* * *

At a bend in the river, five leagues above del Paso, they spent their first night at the Ancon de Fray Garcia where they went into camp. Here the scene changed. Over this stretch travel was slow and difficult for the ground was rough and they had repeatedly to skirt washouts and plough through marshes. On either side of the river ran ranges of barren hills. When they reached their tops they looked out upon a broad expanse of desolate plains edged on the east by the rugged peaks of the Sierra de Los Organos. Camping in turn at El Estero Largo, El Estero Redondo, the Pools of Fray Blas, La Yerba del Manso, and Robledo el Chico, the train moved forward.

EL PARAJE DE LA CRUZ DE ROBLEDO

At a point 22 leagues north of del Paso, in a bleak expanse offering little inducement to encampment, the caravan rode parallel to, but somewhat removed from, the river. The soldiers of the supply train stood in their stirrups, peering this way and that, obviously looking for something. “I promised my wife that I’d add a stone in prayer for her, so I must find it,” Gomez said to the governor, regarding the stone cairn for which they were searching. “But you have no responsibility to come with me,” he said to Rosas and to the men of the escort who rode beside his horse.

“We see it as our responsibility, too,” said Blas de Miranda. “He may have been your wife’s grandfather, but he was also the first colonist to die in New Mexico. It’s important that we keep his memory alive.” He, Nicolas Ortiz, Gomez and the governor broke away from the train and rode down toward a great, bare, roundish mountain on the west bank of the river.

“The original cairn was built almost four decades ago by Juan de Onate and one of his captains to mark a special place,” Gomez explained to the governor. “Every year-and-a-half or so, as supply caravans pass though here on their way to or from Santa Fe, some of us who ride escort for the train do our best to rebuild it. It’s incredible how much damage can accrue to a stone structure in such a short time,” Gomez added. “If, in our passage, we didn’t rebuild it, the cairn would soon lose its definition, its stones merging with those of the landscape. It would be lost.”

“And who is the man we honor?” the governor asked as they rode across the rolling hills of a broad gap between the Caballo and San Andres Mountains.

“Pedro Robledo,” Gomez responded, “an alferez in Onate’s troop who died during the entrada of fifteen ninety-eight. A soldier from Carmena,” Gomez said, “he was my wife’s grandfather, a sixty-year-old gentleman, wearing mail and carrying the arms of Spanish authority who, with his wife and six children, came here as a settler. He provided four sons for the expedition,” Gomez continued, “a number only equaled once as the largest number of soldiers provided by one family. The Indians at the pueblo of Acoma killed one son during the same year. We see the father and his family as symbolic of who we are as a Spanish colony,” Gomez said, “and, therefore, we honor him.”

Scrambling over rocks and through the tangles of brambles and thorns along the brown austerity of a wretched and miserable desert stretch, later to be known as the Jornada del Muerto, the Dead Man’s Route, the soldiers of the escort finally found the gravesite. It looked very much like the so-called Kuba Rumia in Algiers, a curious circular stone monument said to be a Christian burial site, about which there had been much speculation.

“It’s larger than I would have expected,” the governor said, regarding the stone structure they had found.

“Four decades of stones,” Gomez responded, “and the good wishes and prayers provided by the men of twenty-six trains. The site is known as the Cruz or Paraje de Robledo, the Robledo campsite. We’ll rebuild the cairn for the settlers and soldiers of future trains to find and will camp here tonight.”

* * *

Above Robledo, the river wound between steep banks intersected continually by transverse gullies. The gullies, whether shallow or deep, mired the wheels of their carts at every turn. Seeking better ground, the caravan left the river and continued northward.

OJO DEL PERRILLO

The members of Rosas’s train rode through warm days beneath azure skies along the worn and tattered track of the royal road. Their course after leaving the river at Robledo took them through a seemingly waterless stretch of nearly 90 miles that would save them a day or more of travel. The lack of water and the choking dust brought them all—horse, man, mule, and foodstock—to the utmost limit of their endurance.

At one of the few springs the travelers found, they met a small group of Indians who, demonstrating their friendly intentions, knelt in the mud surrounding the spring, crossing themselves as a means of mutual recognition. Drawing their right hand from forehead to breast and then from shoulder to shoulder, they returned their hands to their mouths afterward signifying they required food.

“There are Christianized Indians here?” asked Rosas about the tattooed and painted Indians they found at the spring. “I’ve seen no churches or conventos. Are they members of a hunting party or nomads?”

“They’re a Plains people, Governor,” Gomez responded, “members of the Jumanos or Rayados whom we refer to as the Apaches del Perrillo. They live in three large pueblos which we’ll find north of here near the pass of Abo, and, if people of the same tribe, in rancherias on the Rio Colorado far to the east. They come to the Rio Grande villages for purposes of trade,” he said as they unloaded food from one of the wagons. “The friars tell of a miracle which occurred among these people,” Gomez added continuing his discussion regarding the Jumanos. “Approximately two decades ago, as the friars tell it, the Jumanos were the subject of a supernatural conversion. The priests tell of visits by at least two nuns who were miraculously transported here from Spain for the purpose of preaching God’s word and who assisted the friars in the Indians’ conversions. One, a sister named Luisa de la Ascencion, an old nun of Carrion, had the power to become young and beautiful and to transport herself in a trance state to any part of the world where there were souls to be saved. The second nun, who was able to do much the same thing, was Maria de Jesus, the abbess at the convent of Agreda, who, the friars say, was carried here by the heavenly hosts. She was able to make several round trips in a single day.”

“Do you believe any of this?” Rosas asked with a sneer. “That nuns can fly?”

“I’m not sure what to believe regarding these stories, Governor, so I’ve tried to suspend judgment,” Gomez responded. “When Custos Salas, whom you’ll meet at Santo Domingo, was at the Pueblo of Isleta, where he built the church and convento, he developed a special relationship with the Jumanos who came there to trade. They told him this story and Salas believes it. He went among them with another priest named Diego Lopez, and tells of the miracles of conversion they were able to achieve because of the work of these nuns. The number of conversions was so great that they had to baptize the Indians by swirling a fleece soaked in holy water over their heads. My brother would believe these stories without question,” he said regarding the flying nuns, “but I respond better to fact than fancy.”

“Then you believe the stories to be a fiction?” Rosas asked.

“I place the Indians’ visions in the same category as the mirages one might see on the desert or at sea,” Gomez responded, “those on the desert appearing as ripples on a lake ruffled by the wind, or of trees materializing upside down. I think the apparitions are like the so-called, Fata Morgana, the mirage of a city which my brother and I saw on the Strait of Messina. None of these images is real and yet they’re there as plain as the nose on one’s face. I think I’ll suspend judgment until I know more.”

The governor laughed at Gomez’s statements regarding the Indians’ visions while throwing food at the poor Jumanos who knelt before him attempting to pluck the morsels from the water before they sank into the mud.

* * *

Above the Ojo del Perrillo (Little Dog Spring), where the members of the caravan had found the Jumanos, the caravan continued its northward journey across a harsh, partially denuded landscape of awesome silence and immeasurable distances. It stretched before them, a desert plain with thickets of withered cactus and patches of wild pumpkin, the foliage of which consisted of long, sharp, arrow-shaped leaves, matted clumps of scrubby brush frosted over with silver and greasewood.

* * *

The distances from one paraje, or official campsite, to another were well known, for at some earlier time a soldier had been assigned the unenviable task of counting the steps or paces in each day’s march. The camping sites offered in weary progression included La Cruz de Aleman, Las Penuelas, La Laguna del Muerto, El Alto del Cerrillo, La Cruz de Anaya, El Alto de Las Tusas, and El Paraje de Fra Cristobal. The last site metioned, located six leagues below the inhabited district, should have offered some promise of relief, but it did not. For above it—above the southern pueblos of Senecu, San Pasqual, Teypana, and Alamillo—the Rosas train still had to negotiate “las vueltas.” These were “the turns” where the river doubled back upon itself, making travel extremely difficult.

* * *

Above the turns, the caravan began at last to see daylight. The river, presenting sharply cut embankments, rolling hills, and a widening valley, now offered tiny, greening fields across its flood-plain. And, areas of Spanish habitation were also found. The train stopped briefly at the wine and brandy-producing vineyards of the Gomez estancia at San Nicolas de las Barrancas. Here the governor refilled the leather flask that was always with him. The train stopped for a lengthier period at the Pueblo of Puaray to repair their equipment, badly damaged by the road, and by deterioration resulting from the arduous journey. Then it was on to Sandia, San Felipe, and finally, the Pueblo of Santo Domingo, the ecclesiastical capital of New Mexico.

5

Custos Juan de Salas and Santo Domingo

We’ll go ahead of the train and leave our livestock here,” Gomez said in explanation of his plan to approach the pueblo with only the small contingent of individuals with whom he rode. “We’re forbidden to have our livestock within three leagues of the village.”

“Forbidden?” the governor asked. “Forbidden by whom, I’d like to know? I’ll run my stock wherever I damn well please!”

“You could do that, Governor,” Gomez responded as they rode along a ridge in the vicinity of the pueblo, “but it’s one of the few rules we have that actually makes sense. We could take our animals into the village as you’ve stated, but then my men and I would have to spend our time here keeping our stock out of the villagers’ fields. We’ll take the wagons in, the ones carrying supplies for the missions, but it’s best to leave the rest of the train here where the livestock can find other forage,” he concluded as he, the governor, and Fray Manso broke away from the train and headed toward the village.

As the three rode toward the pueblo, set beyond clean gravel hills, its rich irrigated lands lying below in the valley of the Great River, Francisco Gomez lagged behind with the governor who was surveying the adobe village, viewing its corrals, its extensive orchards, and its produce gardens greening behind adobe walls.

“The pueblo might look like it’s always been here,” Gomez remarked of the village whose brown hulk loomed on the edge of the river, “but, like many of the pueblos on the river and elsewhere, it’s been moved several times. This, I believe, is at least their third village,” he said. “Previous villages built on the banks of the Galisteo and the Great River were destroyed by flood. And there’s something else here which you may wish to make note of,” Gomez added, pointing to structures which appeared physically and psychologically removed from the life of the village. “Notice the location of the churches,” he said. “They’re at least three hundred varas from the edge of the pueblo. They were placed there for strategic purposes,” Gomez added. “It’s a simple formula which you’ll see repeated again and again at each of the pueblos you’ll visit. The distance of the church from the center of the pueblo is in direct relationship to the resistance by Indians there to Spanish rule. As you can see, the Indians here are very resistant, and the structures themselves, their placement and fortifications, attest to the presence of enemies against Spanish authority both within and without the village.”

Rosas nodded in understanding as he examined the three structures that rose before them. Adjoining the south wall of the principal church, a large structure with a central bell-tower and a balcony over its main entrance, was a modest multi-room adobe convento. Its rooms were arranged around an interior courtyard. A covered walkway encircling the interior of the enclosure secluded a claustro, or square court. On the west, the convento itself was of two stories.

Parallel to the main church and abutting it on the north was a smaller church with a window above a large doorway. Fronting the three parallel structures was an atrio, a walled and fortified enclosure of large size, which appeared to double as an exterior chapel and cemetery. Taking a large swig from his leather wine skin, Rosas and Gomez, dismounted and walked through the atrio, where they were met by Custos Juan de Salas, principal of the Santo Domingo church and convento and dean of New Mexico’s ministry. An individual with an attractive face topped by a high forehead, he stood there with Fray Manso who had ridden ahead of the two men. Formal greetings followed, after which the four walked through the convento’s archive room which was finished with wood—and, Rosas thought, set with remarkably fine furnishings—to a small table that had been placed in the patio by an Indian porter. Additional Indians, cooks, gardeners, and waiters, could be seen in the patio and through the open doorways of interior rooms as the Salas party, passing through a dimly lit labyrinth of passageways, made its circuitous way to the patio. Upon entering the interior court, they were surrounded by birds of every description, flitting over, underneath, and through the covered walkway, landing to eat seed that had been spread for them and for a beautiful wing-clipped parrot hopping happily about the flagstone court. A large garden, grape arbor, two peach trees, and a stone-lined well graced the southern end of the compound. Fray Salas bid the group sit on the chairs the Indian porter had also carried there.

When they were seated, Rosas provided the opening salvo saying, “Two churches and an atrio! You must have an enormous number of worshipers, Father.”

“Yes, we do,” Salas responded with pride, “we’ve been very successful in our conversions here and at our visita of Cochiti, and, also, among the Jumanos of the plains where our work was assisted by the Mother of Agreda. We use the atrio as an accessory chapel from which to administer the sacraments on Sundays and on other occasions when the faithful cannot be accommodated within the church.”

“Facing the mihrab, I assume,” Rosas remarked disrespectfully smiling first at Fray Manso and then at Custos Salas.

“Not Mecca,” Salas responded, answering the taunt, “but God. Outdoor worship violates the idea of the mystical body of the Church, but it’s what’s required here by our circumstances.” He smiled first at Fray Manso, and then at Francisco Gomez and the governor. “We’ve had to make many accommodations here,” he added. “Undoubtedly, he said, speaking directly to the governor, “your Lordship will find that he must do the same.”1

“I’ll do whatever’s required to place civil government and secular authority on a secure footing, even if I have to find a demented nun to assist me in my pursuits,” Rosas said, smiling again but getting no response to his irreverent comments.

* * *

Bread and ripe apples, grapes, wine and fresh cheese were placed before them, the cheese taken from a box that was kept in the cool well where it was held in reserve, along with meat, milk, butter, and other food. They continued with their meeting in brilliant sunshine.

* * *