Читать книгу This Scorching Earth - Donald Richie - Страница 9

ОглавлениеTOKYO LAY DEEP UNDER A BANK OF CLOUDS WHICH moved slowly out to sea as the sun rose higher. Between the moving clouds were sections of the city: the raw gray of whole burned blocks spotted with the yellow surfaces of new-cut wood and the shining, felt-like tile of recently constructed roofs, the reds and browns of sections unburnt, the dusty green of scarcely damaged parks, and the shallow blue of occasional ornamental lakes. In the middle was the Palace, moated and rectangular, gray outlined with green, the city stretching to the horizons all around it.

The smokes of household fires, of newly renovated factories, of the waiting, charcoal-burning taxis rose into the air, and in the nostril-stinging freshness of early autumn the bitter-yellow smell of burning cedar shavings blended with the odor of roasting chestnuts. In the houses bedding was folded into closets, and the mats were swept. Beneath the hanging pillars of the early-rising smoke there was the morning sound of night-shutters thrust back into the houses' narrow walls.

Behind the banging of the shutters was the sound of wooden geta—the faint percussive sound of walking—and the distant bronze booming of a temple bell. Jeeps exploded into motion, and the tinny clang of streetcars sounded above the bleatings of the nearby fishing boats. A phonograph was running down—Josephine Baker went from contralto to baritone—and a radio militantly delivered the Japanese news of the day.

A few MP's in pairs still strode the partly empty streets, and a single geisha, modest in bright red and rustling silk, hurried, knees together, to her waiting morning-tea. Greer Garson luxuriated, her paper face half in the morning sun, and a man dressed like Charlie Chaplin, a placard on his shoulders, began his daily advertising.

In the alleys the pedicabs all stood motionless, and around the dying alley fires the all-night drivers yawned and warmed their hands both in the fires and in the morning sun. The early farmers led their horses through the city.

An empty Occupation bus, with "Dallas" stenciled neatly on both sides, made its customary stops—the PX, the Commissary, the Motor Pool—but no one rode. The driver, in cast-off fatigues, smoked one of the longer butts from the several packets he had. An Occupation lady, very early or else very late, tried unsuccessfully to hail a passing jeep.

The blank windows of the taller buildings now caught the rising morning sun and cast reflections—a silver flash of spectacles, a passing golden tooth, or the dead white of a mouth-mask. The food shops opened, and the spicy bitterness of pickled radish mingled with the soft and delicate putrescence of fish, mingled with the odors of the passing night-soil carrier, his oxen, and his cart.

The rolled metal shutters of the smaller shops were locked, but before the open entrances of larger buildings MP's stood and waited, their white-gloved hands behind their backs, their white helmets above their white faces. They stood before the main Occupation buildings, opposite the Palace, across the street and moat—the gray Dai Ichi Building, the square Meiji Building, the tall and pale Taisho Building, and the squat Yusen. To the south rose the box-like Radio Tokyo and, in all directions, the billets of the Occupation. The American flag floated high above them all.

The clouds had drifted out to sea, and the city lay beneath the sun. The pedicab drivers went home, and the carpenters began their work; the geisha sleepily sipped their tea, and the housewives served the morning soup. The railroads, holding the city in their net, brought more and more people into the stations and then returned to bring yet more. The sun and smoke rose into the air, and the radios shouted into the sky, while the streetcars rattled, and the auto horns honked, and the fishing boats cried, and the railroads filled up the city.

The Saturday-morning train for Tokyo on the Yokosuka line left Yokohama Station precisely at six-thirty. At every station passengers had crowded on, and past Yokohama there was never any room. This did not bother Sonoko. She lived at Zushi, and the train, leaving precisely at six, was always half-empty. She could always sit next to a window, either studying her Basic GI English in 12 Simple Steps or just thinking. Her preference was for the latter, and as a consequence her English was not too advanced. This morning both pleasures were denied her, because Mrs. Odawara, from the house across the street, had taken the seat beside her. For half an hour they had talked of nothing but the party.

"My, how lovely it will be," said Mrs. Odawara for the twelfth time. Sonoko had unwillingly invited both her and her family after the second time. Now Mrs. Odawara felt a proprietary interest and kept adding little touches here and there. "I'll bring some sushi, and we have some saké left—oh, no, it's no imposition at all."

"My parents and I shall remain forever grateful," said Sonoko formally, wishing she had never breathed a word about the party to Mrs. Odawara. The thought of its finally occurring had made her talkative, had made her forget that people like Mrs. Odawara are always waiting to pounce upon extraordinary social occasions and make them their own. Since this was going to be so very extraordinary an occasion, she'd had no choice but to invite her.

"But are there enough guests to do the American proper honor?"

Any more and there wouldn't be room in the house. All of Sonoko's relatives—and now the Odawaras! This party wasn't going to be at all what she'd originally planned. It was to have been something intimate, comfortable, democratic, with only a few speeches by her father and a well-organized schedule of parlor games. Now she would rather not have the party at all. But it was too late. The invitation had been accepted; her father had bought an extra saké ration; her mother was assembling the ingredients for "mother-and-child"—a lovely dish which used both the egg and the chicken, to say nothing of frightening quantities of black-market rice—and her brother was cleaning the entire house.

"Yes, there are enough people, I think," said Sonoko.

"But you must remember your position with the Americans, dear Sonoko. This is an important occasion. This may well further your Career!"

Mrs. Odawara knew all about careers, for she had had several. She had been an Emancipated Woman in the Taisho Era, and during early Showa had been one of the first suffragettes in the country. She wore lipstick and silk stockings right through the great Kanto earthquake, and often said so. Then she'd been married twice. She'd even had a divorce, of which she was intensely proud, even though it turned out later not to be legal. At present she was campaigning for birth control.

Sonoko smiled and nodded politely. It might indeed help her career. Ever since she had begun to work for the Americans she had dreamed of becoming a career girl, American-style. In fact, the dream was already becoming true. Since getting the job with the Occupation she had begun to enjoy privileges at home which had never been hers as a schoolgirl. She was, to be sure, supplementing the family income, but that was not the real reason. It was that she was working for the Americans. There were a few Zushi girls who were employed by the nearby Military Government unit, but it was Sonoko alone who made the daily one-hour train trip to the city, and it was she who came back with stories of American kindness, generosity, and nobility which far surpassed those her high-school friends working for the MG could contribute.

And that wasn't all. She had come back one day, for example, with the blouse and skirt, both brand-new from the PX, that Miss Gramboult had given her. The family had been highly gratified by this typically American bit of prodigality and could not admire the blouse enough nor too often finger the luxurious texture of the skirt. Her mother had clasped her hands in admiration, both of the clothing and of her child, and her father had spent far too much in obtaining a basket of ruddy apples to take to the kind American in return. The lovely Miss Gramboult had been so touched that she had actually kissed Sonoko, who thereafter did not wash that cheek for three days.

"One never knows the results of such things," Sonoko answered politely. "It might well assist my career, or it might not."

"Well, it certainly won't unless you put sufficient thought into it," said Mrs. Odawara. Her tone was not nearly so domineering as usual. She was thinking. Sonoko guessed that she was working at further party details, anxious to extract the last morsel of instruction and enjoyment from the American's visit.

Everyone thoroughly misunderstood Sonoko's real purpose in inviting the American lady to her house. They all took for granted that she herself would derive eventual benefit from the visit. But to Sonoko that aspect made no difference whatever. It might have done so if the invited guest had been Miss Gramboult, who had already proved herself generous to an almost idiotic degree, or any other of the ladies in the hotel. But this guest was very special—it was Miss Wilson.

Miss Wilson was more than her employer—she was her friend. Though Sonoko loved all the American ladies dearly, it was Miss Wilson whom she loved the most, even though, oddly enough, it was Miss Wilson alone who had given her no presents beyond the usual Saturday-morning candy bars. It was something much stronger than gifts that bound them together. It was their Souls.

Like Sonoko, Miss Wilson could not be called pretty. Though she did not wear steel-rimmed glasses and did not have to hide her teeth with her hand when she smiled, as did Sonoko, her mouth was too large, even by American standards, and her eyes stuck out a bit far. She had what was called a good shape, however, and her legs were very long. Sonoko admired both these attributes, which she unfortunately did not possess herself, but not to the extent of feeling any the less affection for their happy owner.

But perhaps the strongest of Miss Wilson's many attractions was that she was worldly. Sonoko knew that she was the secretary of a colonel, that she went to parties at the French Mission, that she went often to the American Club, that she belonged to some very exclusive literary organization called the Book-of-the-Month Club, and that her parents were actually Baptists. Also—and this was Bomantic—many times over she had been seen escorted by handsome and gentlemanly men. All of them were, naturally, officers. Sonoko could not imagine her going out with an enlisted man, and that just proved how superior Miss Wilson was. If General MacArthur went with women—other than Mrs. Mac-Arthur of course—he would probably choose to go with Miss Wilson. Sonoko was sure of that!

Then, Miss Wilson always dressed like the ladies in those fashion magazines of which she owned so many and over which the plump Sonoko pored hopelessly every afternoon when her work was finally done. And she had seven pairs of shoes—Sonoko had counted them—all of them high-heeled, with not a sensible pair in the lot. And that proved how really sophisticated Miss Wilson was. She was, in fact, everything Sonoko ever hoped to be, and that was the reason they were soul-mates, and that was the reason Sonoko loved her so much.

"There are no men," said Mrs. Odawara suddenly.

Sonoko, caught with tears of emotion in her eyes, looked at her lap and said: "Well, there's your husband and my father and brother—"

"No unattached men," Mrs. Odawara explained impatiently.

Mrs. Odawara knew all about the desirability of unattached men, just as she knew all about a career for the emancipated woman. This naturally gave her an enormous amount of prestige and an enviable reputation for being progressive. Of course, during the war her reputation had counted against her, but she had overcome that obstacle by working in a factory and staging anti-American demonstrations. She had aroused the admiration of the countryside by systematically breaking every piece of American manufactured goods which she owned. But that was in 1942. Now, over half a decade later, when just everyone smoked and wore lipstick and was progressive, Mrs. Odawara hoarded American goods and kept her reputation alive by acting as adviser on matters Western, particularly on fine points of American etiquette. Thus it was that she knew that all parties with American ladies should have as many unattached males as possible.

"Well, perhaps my brother's school friends could—"

"No good! No, someone about this lady's age. How old is she? "

Sonoko never could guess the age of Americans. They always looked older than they were, just as, to them, the Japanese always appeared younger. "Perhaps thirty," she suggested.

"Well, that's nice. Now, I have a nephew, my sister's boy—she was killed in the air raids, you know—and he's just twenty-eight—that's American counting—and a very well-mannered young man. Of course, he's married, but we won't invite his wife. After all, I've sort of protected him ever since dear Michiko's death."

This was just like Mrs. Odawara—no false nonsense about not mentioning death. She even made a point of standing her chopsticks up in the rice, though it was the worst kind of luck to do so. She was very advanced.

"Oh, do you really think—" began Sonoko.

"Of course I do. I'm calling on his wife today and I'll ask him. It will be quite wonderful—you'll see. The lady Wilson and my nephew will become the best of friends. Won't that be nice?"

"Very nice," said Sonoko, miserably. "I'm forever indebted for your kindness."

Mrs. Odawara took the acknowledgment with a complacent nod. She was so emancipated that she always purposely neglected making the little negative signs of self-disparagement with which anyone else would have received the thanks.

Sonoko did not want this married twenty-eight-year-old at her party. More than ever she regretted the whole business. The party seemed headed for disaster, but now it was too late to do anything about it.

The party meant nothing to her. Far more important were her delightful and personal relations with Miss Wilson. If she could only speak English well enough, she felt sure that she could tell the American lady anything, everything, and that the lady, like a wiser older sister, would understand, would console. Then Sonoko, too, might have become Miss Wilson's secret confidante, holding the doubtless many secrets of the American lady's life and guarding them with her own.

Their relations, Sonoko had finally decided at the peak of her enthusiasm, were truly democratic. Sonoko thought democracy was wonderful. Yet as she thought of the coming party, she felt a certain chill. For one thing, despite her almost daily readings in GI English, which she had purchased after a great amount of deliberation, her command of the language was not precisely secure. For another, the responsibilities of the party were so great that she was actually fearful for their friendship. Miss Wilson was still as lovably democratic as ever, but Sonoko felt herself becoming hopelessly feudal.

"Does he speak English.?" she asked, trying to conceal her curiosity under her customary politeness. If he did, this might help the party a bit. At least Miss Wilson would have someone to talk with.

"Oh, I suppose," said Mrs. Odawara, who didn't speak English herself. She smiled patronizingly. "He too works for the Americans."

"May I ask in what capacity?"

"Yes."

"What capacity is it, please?"

"Something to do with transportation, I think."

Sonoko was relieved. If he was with Transportation and also spoke English, he could really be of help. He might be able to do Miss Wilson some favors, and she him, and they would all be friends together.

"Oh, please do invite him, Mrs. Odawara," she said, turning around in her seat.

Her companion looked at her, slightly startled. "I intended to."

Contented, Sonoko looked at the other passengers. A large farm woman with fat red hands sat opposite her, leaning forward, a large bundle of vegetables on her back. Mixed in with the vegetables was a child who, from time to time, peered through the radishes at Sonoko. Beside the seat there stood a disabled soldier, all in white, wearing his field cap and holding a crutch, his other hand on the luggage rack. His long hair was beautifully parted, and from where she sat Sonoko could smell the pomade. Near him stood several businessmen, briefcases in hand. They were noisily discussing some contract or other. They were not arguing, but were only engaged in a typical business conversation, banging their briefcases emphatically on the other passengers. Beyond them Sonoko could see yet more passengers, standing and sitting. There was room for no more. She occasionally glimpsed the car behind, the Allied Forces car, completely empty.

Sonoko did not question this fact any more than did the rest of the passengers or, for that matter, the rest of Japan. It was well and fitting that the Allied car should remain empty if there were no Allied soldiers or civilians to ride in it. The Japanese, after all, should not expect to ride in the Allied car—except the girls with the Allied soldiers, but then they really didn't count. Just as it was perfectly natural that the sidewalk snack-bar of the PX in the Hattori Building at Tokyo's busiest crossing should sell Coca-Cola and popcorn and hot dogs to the soldiers and that the little street children clustering round should get none. This was as it was and as it should be.

It never failed to delight and amuse Sonoko that truly democratic people, like Miss Wilson, should think differently. It was admirable of them, but also very amusing. Quixotic was the word she wanted, but she'd not read far in Western literature. If Sonoko had ever consciously thought about it, she would have freely admitted to herself that, had the war ended differently and were she a colonel's secretary in New York, she would think nothing of the Japanese Army's eating sushi and tempura in front of Macy's while the little children from the Bronx and Brooklyn got none. But Miss Wilson bad been much upset and called the Hat-tori snack-bar an atrocity. When Sonoko had finally understood the word—it was the same word the Occupation-controlled papers used in speaking of the rape of Nanking—it had seemed so irresistably funny, applied as Miss Wilson applied it, that she'd giggled about it all day long. Miss Wilson was just like that proverbial American she'd heard of who possessed a heart of pure gold.

Her reveries were interrupted by Mrs. Odawara, who had also been thinking.

"We must have a Bible reading," Mrs. Odawara said suddenly but resolutely.

Sonoko closed her eyes, stricken. Mrs. Odawara was progressive and therefore Christian.

"Of course we must," continued Mrs. Odawara reasonably. "It's Sunday, isn't it?"

"Yes, but..."

"You're not suggesting that the American lady isn't Christian?" She made it sound rather horrible. "And she is coming out early, isn't she?"

"Well, in the morning."

"Just so. She won't have had time to go to church, and so we can hold a reading. Perhaps even a little prayer meeting too. Oh, she'll like it. It will be just like home—Sunday morning and so forth. I know their ways, these Americans.... Let me see—why, I believe I have a large colored picture of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, and we can put it up in the tokonoma."

"But—she's the guest of honor," said Sonoko faintly. As such she would have her back to the tokonoma—the small alcove which had already been most carefully arranged with their finest scroll-picture and the most subtle arrangement of autumnal flowers—and would consequently hold the un-Christian position of having her back to the Lord and Saviour.

Mrs. Odawara gave her a long, hard look. She had her own opinion of outdated and reactionary Japanese customs and superstitions. "But, my dear Sonoko, she is American," she hissed.

There was no denying the logic of her argument and, perhaps, a small prayer wouldn't hurt anything. Her own parents were sort of Shinto, and her brother had just recovered from a passing enthusiasm for Zen Buddhism—brought about by his judo practice and his Chinese-ink drawing lessons—but these feelings would certainly not preclude polite participation in a short, a very short prayer meeting. If only Mrs. Odawara didn't start on birth control. She couldn't stand that. It would be most rude, for after all, where would Miss Wilson have been if her parents had practiced birth control?

"Yes," said her neighbor, for it seemed all settled now. "We will read a part of the Book of Exodus—Israel in Egypt, you know. It will have a contemporary flavor, quite befitting the presence of a member of the Advancing Forces." Unorthodox though she was, Mrs. Odawara had adopted the standard Japanese euphemism for "occupying army."

"It will make her feel her position and will, in a way, be a subtle compliment," continued Mrs. Odawara. "You see—we are Egypt, and she is the visiting Israelite. It is very fitting and will furthermore lend a good moral tone to the party."

"But what about the plague of locusts and the darkness over the land?" asked Sonoko. As part of her education she had attended Mrs. Odawara's Bible school. The objection also occurred to her that the Israelites had been brought to Egypt as slaves. "I doubt that Miss Wilson would too much appreciate the—"

"Obviously," Mrs. Odawara interrupted savagely, "we're not going to read that part. Besides, since I'm reading it will be in Japanese." She fixed a stern eye on Sonoko, just in case there might be a desperate last-moment refusal.

Sonoko turned her head toward the window, determined to be rude if she possibly could. As she well remembered, Mrs. Odawara read slowly—very slowly—and with maddening emphasis. But her neighbor didn't even notice and went on about the virtues of Christianity and birth control, the iniquities of Shinto and Buddhism.

The girl scarcely listened. She looked out on Tokyo and saw how much it had changed since she'd first begun these early-morning rides. It was like maple trees in autumn: one didn't notice the leaves gradually turning red and yellow until, one day, the mountain was afire with them. So with Tokyo, she had not noticed the new buildings, the new streets, the new people, until now when she looked from the window and suddenly realized that the entire bombed-out stretch of Kawasaki, which she remembered as a plain of ruins, had been completely rebuilt.

At Tokyo Station Mrs. Odawara was still fairly budding with suggestions, but Sonoko with a low bow put some distance between them, and even Mrs. Odawara had to respond to a bow. Thus, each bowing to the other, they moved farther and farther apart, and Sonoko, hidden by the morning crowd, left her companion shouting into the recesses of the station.

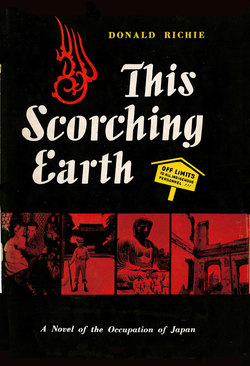

Once in the billet she punched the time clock, pleased as always that she was five minutes early, and walked up several flights to Miss Wilson's room. It never occurred to Sonoko to resent the fact that Japanese employees were not allowed to use the elevators, and the signs "Off Limits to all Indigenous Personnel" remained for her but delightful examples of military English at its sonorous and incomprehensible best. The great delicacy with which the signs avoided the nasty word "Japanese" was unfortunately completely lost on her.

At Miss Wilson's door she hesitated and finally decided not to go in. The dear American must have her sleep. Sonoko could just picture her there, so innocent and childlike in her little pajamas, like a large and expensive doll, her eyes shut, sweet dreams painting a smile of cherubic peace on her generous mouth. Almost in tears, Sonoko turned away from the door.

Just on the other side of the door an extremely vivid Bengal tiger crept through the bamboo, its eyes shining yellow-ochre, about to pounce on a half-used box of Kleenex and a hastily tossed brassiere. Against the other wall was a large glass case containing an equally large doll holding a spray of paper wisteria. Around its neck had been hung a sign reading "Off Limits to Allied Personnel." Beside it was a plaster miniature of Mount Fuji, the crater of which was hollowed out for an ashtray. On the wall was a Nikko travel poster in full—too full—color. Hanging above it was a paper dragon, and beneath it a silk slip. Against the other wall hung a large Japanese flag, scribbled all over in ink, the brushed characters faded into the silk. Everyone who'd signed the flag was probably now dead.

In the bed was a long, sheeted figure which coughed miserably and hoarsely. Its long brown hair was half covered by the sheet and the pillow. At the other end a foot was sticking from under the Army blanket. The foot had red toenails. Beside the bed the alarm clock clicked once and, in half a minute, rang. The figure, its head muffled in the sheet, put out an arm and turned it off, then sighed.

Gloria sat up painfully, her eyes still closed, and covered her face with both hands. She got unsteadily to her feet, licked her lips, and walked to the mirror. Her roommate was gone for the weekend, so she didn't bother with her robe. She always slept naked. Now she had a hangover.

At the washstand she took a long drink of cold water and opened her eyes. It was after some effort that she remembered today was Saturday. But where was she? She glanced covertly around the room and realized she was in Japan and not in Indiana. For years she had had an early-morning fear of opening her eyes and seeing the tiny doilied bedroom that was hers in Muncie. She had opened her eyes in all sorts of beds and on all kinds of bedrooms, but still the fear remained.

This morning even the bedroom didn't reassure her. Something was the matter. She began to brush her hair, fifty strokes every morning like Charm said, first thing. On the fiftieth stroke she remembered what it was: she couldn't remember what she'd done last night. Dropping the brush, she looked into the mirror and tried hard to remember. Actually she knew, from experience, what it was she'd probably done. She just couldn't remember with whom.

It had been like this every morning for years now. The alarm would drag her safely away from vaguely terrifying dreams about God and Father and Mother and Indiana. Then, washing her face or brushing her teeth or combing her hair, she would suddenly come to realize the extent of her sin. The pattern was dreadfully familiar, having been repeated so many times, but the reality of sin was always naked and new and startling.

Every morning at seven she was at her most vulnerable. Naked and alone, she stood before the mirror, hiding her face in her hands, her guilt lively as a child within her. The bedroom, despite Fuji and the painted tiger, seemed in Indiana, and soon she would force herself downstairs, to her parents, to the poached egg on soggy toast—knowing she was a sinner.

Later, after she had put on her clothes and her face, she would also put on her attitude. Her parents were narrow-minded bigots. If they thought her spawn of the devil, she returned the compliment. After all, she would think, it was just a matter of which Satan you chose.

But now she was still cringing before them as before a whip, and hungry guilt gnawed. It was worse than usual this morning because she couldn't remember her partner in sin of the night before. If she could only identify him, then some of the early-morning shame would rub off on him, but this way... it might be just anyone.

Well, someday it would be too late. There was always the chance that some day precautions would be forgotten and that she would pay, in that humiliating female way, for what she laughingly called, in the bright light of full noon, her very own "American way of life." And perhaps this was the day. Frantically she began gathering up her clothes and, just as frantically, began searching through her memory.

She remembered going to bed, sort of. She also remembered kissing someone—perhaps good-by, she hoped—in a sedan. Before that it had been either the Officers' Club or the American Club, but she couldn't remember which. And whom could it have been with?

Shivering, she put on her robe, then began brushing her hair again, feeling better each time the brush hurt her. She brushed harder and harder, until the hair started coming out. Then she stopped, thinking that one really mustn't carry masochism too far. She looked into the mirror, particularly at her mouth and eyes.

"Well, you'll never be a pretty girl," she said softly, and at once felt better. "But you do have such lovely hair." She always felt better when she could make a joke.

There was a soft knock at the door, but Gloria paid no attention, knowing it would immediately open. It did, and Sonoko, smiling, walked in with clean towels over her arm.

"Good morning, Sonoko," said Gloria brightly, hoping to sound a good deal brighter than she felt.

"Ohayo gozaimasu," said Sonoko. Then: "Hi, there." She always gave a bilingual morning-greeting, the first to show respect for herself and the next a genuflection to all great Americans. Walking to the opposite bed, still made-up, she pointed questioningly to its undisturbed covers.

"Weekend trip. Far, far away," said Gloria, making vaguely distant gestures with her hands.

"So desu ka?" said Sonoko and put the towels on the chair.

Gloria was examining her eyebrows, which she thought looked as though they'd been trampled on. "Sonoko, be a perfect lamb and run out and see if one of the girls can spare me an aspirin. I've got a little headache." Little, my god! Her head was coming off.

Sonoko looked at her and smiled, as though Miss Wilson had recited a poem, then went back to making up the bed.

"Sonoko—asupirin."

"Ah, so," hissed Sonoko, her eyes blank behind her glasses, "asupirin—I catch quick—I hubba-hubba."

She clattered out of the room, leaving Gloria wincing first at the clatter, second at Sonoko's GI English. It always unnerved her when these people used it—which was often. It was as though the Great Buddha at Kamakura had come out with Brooklynese. She slipped her feet into sandals and went down the hall to the shower.

In the shower she suddenly remembered whom it was she'd been out with. It had been Major Calloway, of course. From her own office. Imagine having forgotten! A gentleman of the old school. No passes, only comfortable, cozy talk of the just-you-and-me variety. Much explanation of power politics behind the command, climaxed by the revelation of who really ran the office—the Major himself. All of this interlarded with compliments to Gloria about her dress, her personality, and her soul—in that order. They talked shop for a while; then he told her how lonely he was and what a nice homebody she was. She'd used her little-girl smile and folded her hands. Receiving homage from the peasants was always fun.

The warm water was reviving her memory more and more. They'd had steak and apple pie at the American Club, and in the sedan coming home she'd gotten kittenish and wanted to wade in the Palace moat until he told her it was eight feet deep. In front of the hotel they had kissed good-night, very decorously, using only the lips, and she'd come in and gone to bed. As simple as that! She hadn't done anything at all. Because no one had asked her. Heavens, the Major probably had honorable intentions!

Gloria put her face under the shower. She was awake and clean. Her early-morning fears were already down the drain. She'd scrubbed her long legs and her flat stomach until they were red, and she felt much better for it. Muncie seemed just as far away as it actually was. She was in the Glamorous Orient and was one of the most glamorous things in it. The hot water gave out and put an end to further reflections for the time being.

As she dried, she said to herself very softly: "No, not really beautiful, you know, but interesting looking, awfully interesting." She had no doubt that this was what they—the men—said about her, and she also had a fairly accurate idea of what the women said. Holding the towel, she thought of the hundreds of days she'd been in Japan. Each had begun with a shower, and almost every one had ended with a man. She couldn't even remember them all.

"This is a rare and sober moment, Gloria," she told herself, and tried to remember all the men she'd ever known in her entire life.

In such moments as this she'd often thought of compiling a little history. Nothing too elaborate—just the man's name, the date, and the place, if she could remember it. Single spaced. About a dozen sheets should do it. Then she could subdivide the total and cross-reference it according to the different nationalities. There was the attache at the French Mission, the nice British sergeant at the Union Jack Club, that lovely Italian correspondent. ... Then, after she had divided them, she could take percentages. Of course the Americans would win, but it would be interesting to find out by how much.

But it was hopeless. She had forgotten too many. As she tied her robe she decided that the only immoral thing was her forgetting. This comforted her. That was her only sin, to have forgotten anyone with whom she had shared what one very earnest second lieutenant had once called "the holy happiness." He was Southern and had religion, she remembered; afterwards he'd tried to baptize her with what was left of the whisky.

Well, she'd start a diary soon. That should help her memory. Each entry burned and the ashes stomped on and eaten as soon as written. No lurid details—just the name and her thoughts for the day. What names would not grace its pages! Who would be next?

This was a favorite game, but the odds were hopelessly against her. It never turned out the way she hoped. That gorgeous Depot sergeant was virtuous; the dark correspondent at the War Crime Trials had gone completely Japanese; and the cute little dancer with the USO hadn't liked girls very much. Alas, one always remembered the failures best.

The next just might be Private Richardson, also from her own office. The only trouble was that they'd built up a kidding relationship which rather well precluded their ever getting within five feet of each other. Besides, she'd heard he had a Japanese girl. Really, it was sinful the way they had become such competition. (Wonder what our brave boys would say if we started running around with Japanese men?) Oh, well, she'd just have to wait and see about Private Richardson.

Back in her room she carefully turned her back to Sonoko and put on her pants, brassiere, and slip. The girl was plumping up the same pillow for the tenth time that morning.

"You have a boy friend, Sonoko?" she asked.

Sonoko giggled, covered her mouth with her hand, and said: "Nebah hoppen."

"Oh, some day it will," said Gloria airily, zipping her dress up the side. "A nice .. . farmer."

Sonoko giggled from across the room.

A farmer! Gloria had never even met a farmer, not the kind with dirt under his fingernails and sweat in his armpits, that is. That was another way she could cross-file her little history: occupations. Except that it wouldn't be quite fair. Her wishes hadn't always been observed in the matter. It was the white-collar boys, the lieutenants and up that she always got tangled with. They were somehow so much easier. They spoke her own language, and they were always available, being as neurotic as she.

How, she wondered, did one go about meeting a farmer, a truck driver, a boxer? The lower classes were always so damned suspicious. Enlisted men the same way. And, at least, you could trust an officer to keep his mouth shut, which was more than you could expect from sergeant on down. Except, perhaps, Private Richardson.

She wondered if part of his attraction didn't come from his being Private Richardson. She tried to think of him as Major Richardson—General Richardson. Sure enough, some of the brightness faded. A part of the attraction? It was apparently the whole thing. Well, she'd just have to see. Now, when could she snare him? Tonight perhaps?

Oh, no! She sat down on the bed, one foot in high-heels. No, not tonight. All morning long she had felt that all was not well with the world, and now she remembered why. Carried away the night before, she had said yes when Major Calloway had suggested dinner and the opera this evening. He had seemed such a dear after their dozen-odd Scotches. Now, in the merciless light of day, she saw him in his true form.

"Not a deer, but a boar," she said to herself. But even this reminder of ready wit didn't cheer her. Here she'd gone and ruined a perfectly good Saturday night, just to be brought home and pecked on the lips. Much too late to do anything about it. After all she was the Colonel's secretary, and he was the Colonel's executive officer.

"Well, we're obviously made for each other," said Gloria, wriggling into the other shoe. "The Fates are against us."

She stood up and put on the last finishing touches before the mirror. Sonoko, looking as though she was about to start fluffing the pillow again, peered shyly over her shoulder. The pancake make-up, the mascara, powder, and lipstick were all understood by Sonoko. It was in the last-minute attentions that mystery lay. She watched while Gloria deftly unclotted two eyelashes, cleaned a tiny speck of lipstick off one of her front teeth, and gave herself a final spray of scent. If she ever wore make-up, Sonoko often thought, she would do just as Miss Wilson did, even if she had to put lipstick on her teeth in order to take it off. It was in these final intuitive touches that all true art lay.

Gloria saw the steel-rimmed spectacles over her shoulder and handed Sonoko the atomizer. "Go on," she said, "only don't waste it. It's Sin Incarnate or some such thing, and I'd never be able to afford it if the PX didn't mark it down ninety percent. Go on. Dozo."

Sonoko giggled, holding her hand in front of her teeth, and carefully put the atomizer back on the table. Gloria waved good-by and started for the door. The giggle suddenly stopped, and the dark eyes behind the steel-rimmed spectacles grew wider.

Gloria smiled politely, one hand on the doorknob: "What is it, Sonoko?"

Her room girl swallowed, then said: "You no forget—o-pahti tomorrow?" It was midway between a declaration and a question.

Suddenly Gloria understood. Oh, god! She had forgotten—but completely! So, as was usual with her under these circumstances, she shook her head, smiled in a special way that wrinkled her nose, and said: "You bet your life I didn't forget, little old Blue Sonoko. I can hardly wait." And for Sonoko's more immediate comprehension she added a bit of pantomime.

They parted with bobbing on one side and nose-wrinkling smiles on the other.

Waiting for the elevator, Gloria felt like kicking herself. Now she perfectly remembered accepting an invitation which at the time seemed to be for some vague, indefinite future. She'd been half-asleep, still in bed, defenseless. Now she was trapped. Oh, well, so she was trapped—so what? She could always learn something. And if tonight was going to be wasted with the Major anyway, she might as well have something to look forward to when she woke up Sunday morning.

Her own nature never failed to delight her. So philosophic. She always said there was so much to be learned from the little things in life—then laughed herself sick; but, nevertheless, it was true—there was. Now, a lot of other American girls under like circumstances would have pleaded off—sick headache or the like. Not Gloria—true blue, she stuck to her word, and what's more, damn it, she'd enjoy herself even if it killed her.

Not that it was likely to. In fact it might be fun—afterwards. She could tell about the quaint little paper house; how meekly she took off her shoes; the good, good soup—like Mother used to make—and the squealy little dishes that Gloria, good sport that she was, ate right along with Papa Sonoko—octopus, seaweed, fish heads, and the like. And then they'd sit around the family koto, and she'd lead them in "Home on the Range" or something like that. Pure strawberry-festival—Japanese style—but it would make a great story Monday morning at the office. And Private Bichardson—he'd be thinking a little about the strange home-life of his Japanese biddy before her tale was done.

Already flushed with success, she smiled at the elevator boy and was carried down to the basement dining room. Under the mockery, the laughter, and the attitude, she was dimly aware of a real curiosity and a real pleasure at being invited. But, what the hell, if one wore one's heart on one's sleeve and one's feelings on one's shoulder, one could well expect to end up with neither sleeves nor shoulder, and she, for one, needed hers. So, when she walked into the dining room, she felt her usual cynical self.

At the same time she remembered she'd forgotten to put out the candy bars she usually gave Sonoko to take home to the countless brothers and sisters she doubtless had. Oh, well, she gave the girl enough of a treat just being around. She suspected Sonoko had a crush on her, and this made her feel quite good. Tonight she'd put out the candy and, after the sleep of the innocent, lug it out to this god-forsaken place called Zushi or Fushi or Mushi. She was such a good kid, Gloria was. A real heart of gold—just like the proverbial whore.

It was still early. The tables didn't fill up until just before nine. At nine everyone was supposed to be at work. Today was Saturday and most of the tables would remain empty: many of the female members of the Occupation found it convenient to take sick leave on Saturday mornings—it gave them such an early start for their weekend dates by the sea or in the mountains.

Gloria saw Dorothy Ainsley sitting alone, and before she could turn away Dorothy had seen her and was making frantic motions with one hand, the other holding a piece of toast.

"Oh, darling, am I glad to see you!" Dorothy shouted halfway across the room. "I feel just like an interloper or something." She smiled and moved her chair further around the table, patting the other with one hand.

Gloria sat down.

"I was up quite early—shopping, you know, at the Commissary. Us wives! If you don't get there early, all the lettuce is gone, or something. And you know Dave! He loves his lettuce so. Well, I was passing by in our car and I thought: I'm hungry, that's what I am. So I told the girl on duty I'd forgotten my purse because, natch, I don't have any meal chits, and then sat down over here, out of harm's way, and was feeling so guilty. That is, until I saw you."

"I'm so happy for you, dear," said Gloria, while she thought: You lie in your teeth, you slut. You just want one good witness who'll say she saw you here and who'll believe your silly Commissary story. Little me, however—I know what you're doing, though maybe not who with. One of the few good things about our little colonial society is that people know what other people do. So just don't give me any of this marriage crap. I wonder what you told your husband.

"Of course, Dave will be just furious. He doesn't like me to get up early. It's bad for a singer he says. Imagine! Besides—he's so silly—he says he likes to watch me asleep." She giggled self-consciously, one finger extended away from her toast.

Gloria could just picture this. She didn't know Dave Ainsley very well, but she'd seen that faithful-dog look following his beautiful, talented wife around, his smile half-apologizing for her, his eyes shining with devotion. Jealous too. Tried to thrash a sergeant once who made eyes at her. And the poor soldier was probably only acting on advice given him by a lieutenant who'd gotten it from a major. Dorothy was such a snob. No one below field grade. Poor Dave. Gloria could imagine him tiptoeing around their apartment—complete with artificial Ming vases made into lamps—casting loving glances on his sleeping wife. On the nights she sleeps at home, that is.

What would he say if he saw her now, she wondered. Sitting there fat as a grub and almost purring with contentment. Her face was still pink. Gloria guessed that he had never seen her this satisfied. Dorothy would walk in on him at work about an hour from now, still rosy, having been home, washed, and depilated, with some whopping story about a cousin or an aunt in town and that she just couldn't get away and it was too late to call because she "didn't want to disturb your rest, Davie-boy." Or maybe she'd use that one about furthering her career.

Or else she'd turn up with what Davie-boy always called "one of Dorothy's"—a real stunner involving a sedan breakdown and how she partook of Japanese hospitality and how nice they were to her and sat her in the place of honor and how she could scarcely gag down a breakfast of seaweed, fish, and tea, but how low she bowed afterwards—right there on the tatami—and what really exceptional people they were, too. Not at all usual, you know. Nothing run-of-the-mill ever happens to our Dorothy. And all of this would be told in her low, modest, little-girl voice, the one that doubtless sent her husband into ecstasies....

Dorothy broke into Gloria's thoughts, saying: "You know, dear, we're rather alike. I mean, we really do seem a bit similar. Don't you think?"

Gloria looked at her, noticing with some satisfaction that Dorothy was getting a bit saggy. If she was a singer, her diaphragm looked pretty unprofessional. She always kept her profile high too. That was so the extra chin wouldn't show. But, there was no doubt about it, she was quite beautiful in that brittle, china-doll way that men unaccountably seem to find so attractive.

Gloria decided they weren't at all alike and, as coldly as possible, said: "In what way?"

"Oh, I don't know. We seem to have found ourselves out here—in Japan, I mean."

"What have you found?" asked Gloria, whose head was beginning to ache again. Sonoko hadn't brought the aspirin, and eight-o'clock solemnities with Dottie Ainsley were just too much.

"Well, for one thing, a husband," said Dorothy seriously. "They're necessary, you know. All girls should be married." She suddenly smiled, as though what she was saying could not possibly have any personal reference. Nor did she try to explain the illogical sequence of her thoughts from their being alike to husbands.

Gloria stared at her in mild disbelief. Just what did she think she was doing? Gratuitous insults were a bit coarse, even for Dottie.

"Well, Mrs. Ainsley," she finally said, "we can't all be as fortunate in our choice of husbands as you were."

"Don't misunderstand me, dear. I mean, if a girl has a chance of marrying these days, she ought—no if's, and's, or but's about it. She really should. What she does is her own business, but she ought to have a husband, first."

"Your meaning is awfully subtle," said Gloria, "but I think I'm catching on."

Dorothy began sipping her coffee daintily, and Gloria's oatmeal arrived to fill the gap in their conversation. As she ate it she decided that Dorothy's meaning actually was rather subtle. Either Dorothy guessed that other people knew about her, and hence the girls-will-be-girls kind of talk, or else ... or else she wanted Gloria to get married for reasons best known to herself. At any rate, she had looked uncommonly honest when she spoke, just as now, sipping her cold coffee with a pinkie in the air, she looked uncommonly uncomfortable.

The silence after their orgy of intimacy was getting a bit heavy, Gloria thought. She was about to ask whether the plates' willow pattern was Chinese or Japanese when Dorothy, apparently feeling the same, gave a little scream and bent under the table.

"Oh, my, what pretty shoes! Where did you get them?"

Gloria stretched out her legs so Dorothy could see the shoes without disappearing completely under the table. "The PX," she said.

"Don't tell me you get your clothes there! Why, I haven't been near the place for years. Not since I was what they call a 'vocalist'—whatever that is—with the USO and all that, you know. And that—well, just between us, it's been ages ago. No, after I met Dave (he made me over, you know) I started buying from New York—by mail, natch (and it takes just forever getting here!) and then, of course, there's that wonderful little tailor in Hong Kong. But those shoes you have there—they rather interest me. Any other sizes?"

Now, this is our old Dorothy, thought Gloria. It feels good to be back in a mutual understanding again—the understanding that we loathe each other. "I don't think so," she said. "If they do, they're larger."

"Larger? Oh, not really!" Dorothy sipped her coffee and tried again to pretend, somewhat less succesfully, that she had meant nothing personal. "Why, my little feet couldn't begin to fill those up."

You're asking for it, thought Gloria. She'd known girls like Dottie before. Real bitches. Just couldn't stand not tearing in with their little claws. Anything that would hold still was fair game, no matter what. Her poor husband must be just a mass of tangled ribbons by this time. She was the kind of healthy American girl who would write a four-letter word on the upturned lid of the ladies' john in lipstick—backwards. Then stick around and watch the fun when the next occupant, in a cool white blouse, walked out. She'd heard men's cans were all scribbled up. They should see the ladies'—after a crowd of Dottie's type had gotten through with them.

Gloria looked at her shoes. "Well, they're comfortable."

Dottie had apparently expected to get clawed back. She looked disappointed. "Oh, I can see. They're just lovely—exquisite." She sighed shortly. "I only wish I could get things like that." She smiled, her just-between-us smile, which wrinkled up her nose and never failed to infuriate Gloria.

"Oh, you might be able to," said Gloria smoothly. "Perhaps one of the officers you know is in the Quartermaster Corps, or Procurement, or even the PX for all I know. If you really can't bear to go near the PX's yourself, perhaps you could get one of them to scout for you. Yokohama, Kobe, Nagoya—you know."

"Well... but I really don't know any officers that well," said Dottie after hesitating just a second too long.

She was such a bad liar. Goodness knows it was difficult enough to be a good one. Gloria was a good one, but even she forgot her lies eventually and got into trouble. So she decided to be charitable and say nothing more.

Dottie gave her a hard little glance, disagreeable over her cup. She put it down with a tiny clatter, then softened almost at once and became again feather-brained and flighty:

"Well, I must run. Dave will be furious. You coming?"

"Yes, I'm off to work."

"You're lucky, you know," she said, turning her head whimsically. "I wish I was a career girl again. But I'm not. Just a drudge—a regular Hausfrau type. I bet I couldn't even hit a high C any more. And, you know, my range used to be four octaves. I forget who it was called me the Lily Pons of the Occupation. Silly, but fun." She laughed. "Know what Dave used to say about my range? No? He used to say that I was composed of a bass, a tenor, and a small boy who got pinched. Cute, huh?"

Gloria gave a sick smile, and Dottie rattled on: "Oh, hell, I just remembered—tomorrow's a big Japanese party. They're picking us up. That means I've got to get the servants busy cleaning the house—four of them and not a brain in the lot."

"Real Japanese party—or just Japanese-style American?"

"Oh, the real thing. Ex-zaibatsu or the Imperial family or something. Dave's business. On the paper, you know. Tatami, hashi, the works—all-night deal."

"Well, that might be pleasant."

"Pleasant? You ever had a Jap breakfast?"

"Often," lied Gloria.

"Well, you're a better woman than I am then."

Gloria wisely said nothing to this.

"Oh, by the way, did you hear what happened to Lady Briton last night?" asked Dottie, somehow seeming to want to delay the moment of parting they both wanted so badly.

Gloria groaned. Not Lady Briton again! Gloria bet that at any given moment of Tokyo's social life the antics of Lady Briton would be on a dozen tongues. She was the wife of one of the Australian Mission people, a big horsy woman who was attempting to establish a Society for the Protection of Our Dumb Friends—SPODF she called it, but to the rest of Tokyo it was SPOOF. It was to rival the Tokyo chapter of the SPCA, of which the British ambassadress was patron.

Dottie continued: "Well, you know, a couple of weeks ago she saw some trained dogs in Asakusa or some such place, and she decided they were being cruelly treated—they juggled or sat up or something. Of course, she cares about animals just about as much as I do. But she just can't stand seeing that English woman in the newspapers all the time. And so she confiscated the whole troupe, dismissed the owner out of hand—the Australians are like that, you know—and decided to play Lady Bountiful to all the animals. She thought they'd be good entertainment at her parties, juggling and all. But they wouldn't do a thing—just moped. They were nasty too; got into some of Randolph's—that's Lord Briton—old ambassadorial papers or something and chewed them all up. Well, last night was the payoff. They'd been just darling little nuisances before, but last night one of them bit Mrs. Colonel Butternut on the thigh when she was down on the floor being the the head of John the Baptist during charades." She smiled. "Isn't that a scream!"

"What happened to the dogs?"

"Well, this was one time, believe you me, when our dumb friends got short shrift. She probably had them drowned."

"All of them?"

Dottie shrugged her shoulders—this wasn't the point of the story. "And Mrs. Colonel Butternut is in St. Luke's under watch—she might have rabies. Can't you just imagine her frothing at the mouth? She's done it all her life, but until now no one thought anything of it. Oh, it's a panic!" She stood up.

Together they walked past the girl who took tickets, and the headwaiter at the door bowed to them.

"Why don't their clothes ever fit, I wonder?" asked Dottie, looking vaguely at the small man in the dress suit too large for him.

"Their Japanese clothes do," said Gloria.

"Oh, those!..."

They were silent as they walked through the revolving door into the already dusty sunlight.

"Well, that was a nice breakfast," said Dottie, "but tomorrow's won't be."

"What I like best about spending the night with the Japanese," said Gloria, who had at least spent nights with Americans in Japanese on-limits hotels, "is that no one says good-morning to me until I'm presentable. They have a tacit agreement that you're not even visible until you get your face on and are ready to meet the world." She'd read this in a book somewhere.

"Yes, I know," said Dottie. "They do act that way, don't they?" She was anxious lest it seem she didn't know as much about the Japanese as Gloria, and was at the added disadvantage of not having read a book through since finishing high school.

Directly at the billet entrance was an Army sedan, the young Japanese driver leaning against its shining fender. He stood away from the car as they came out and made a tentative motion toward the handle of the rear door, his black hair shining in the sun.

Gloria wondered whom the sedan was for. You never saw them waiting in front of the billet except very late, when the field-grade officers were saying good-night to their girls. The hotel was for lower-rated civilian girls, who never got to use anything better than a jeep. Only the upper grades rated sedans. She found herself wondering about Dottie, who could get a sedan on the strength of her husband's high civilian rank. So, then, whose transportation could this be but Dottie's? But she'd said she'd come in her own car. Then Gloria remembered that the Ainsleys didn't own a car.

Gloria glanced at Dottie, who was squinting in the early-morning sun. Such a poor liar. This was certainly her transportation, ready and waiting, yet she couldn't take it because she'd already told Gloria about the car. And she needn't have lied either. Lots of wives used sedans to go to the Commissary.

While Dottie hesitated on the hotel steps, Gloria swiftly reconstructed the events of the night before. Dorothy had probably left her husband rather late, pleading relatives or something. Then the adulterous meeting, perhaps at his billet. She'd probably sneaked out in the cold, dark morning when it was too early to go home. Perhaps she'd tried to hail a passing jeep. Then the sudden determination to have breakfast. It was probably a combination of hunger and the perverse desire to expose her own position. Now the finale—home in the sedan which she had probably called just before going in to breakfast. But Gloria's presence had spoiled this last touch.

"Well," said Dottie briskly, "I parked the car around the corner—past the station as a matter of fact. Thought I'd just walk to the Commissary. Exercise, you know," she concluded brightly.

"Yes, it's only halfway across town."

"What? Oh, yes. Well, one can't get too much exercise." Then, anxious not to seem to be avoiding the obvious, she said: "These poor drivers!"

"Why poor?"

"Oh, I don't know. It's in their eyes—that lovely melted-chocolate color, you know. And then, Japanese men are always sad looking anyway, like dogs left in the rain. Breaks your heart." Dottie was not without her sensitive side.

"The women look comparatively dry," said Gloria.

"Oh, them! Isn't it strange—the men look just like dogs, and the women look just like cats. You know—cute little triangle faces, button noses, and those lovely slanting eyes. It's really the animal kingdom."

"Maybe that's why Lady Briton likes it so much over here."

"Yes," giggled Dorothy, "someone should start a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Japanese."

Someone really ought, thought Gloria. It wasn't that the glorious Occupiers were cruel. They were merely thoughtless. There was something about having plenty in the midst of famine that made people thoughtlessly cruel. When she was good and drunk Gloria always felt like apologizing to beggars. So far she had restrained herself. She didn't like Dottie's saying what had so often occurred to her; so she asked if Dottie was going to the opera.

"Well, if you call it an opera, yes. It's good business, you know."

"You don't like Madame Butterfly?" asked Gloria.

"Oh, adore it! Simply adore it! But that soprano! Know the girl. A nice voice, though a shade overly cultivated—that is, when you realize that she had nothing to cultivate in the first place. Can't hear her except in the first three rows. Bad breathing, that's what Mme. Schmidt says. You know her, dear? My old sensei—that means teacher, you know. From Vienna and just the sweetest old lady ever. Poor thing—half-starving now. Whenever I take my lesson I go to the PX and just load up—crackers, cheese, sardines, that sort of thing, you know. I suppose they have a banquet after I go. Awfully odd position she's in—white, natch, and yet can't use the PX or, well, any of the Army things. Can't even ride Army busses, or the Allied cars on the railroad. Doesn't go out much—no shoes! Of course, she was here all during the war, and I suppose that's why. And the CIC is always investigating her—as though she cared about Hitler or Mussolini or anything but music. She'll be at the opera tonight probably—I'll bet she's off borrowing a pair of shoes right now. That soprano is another pupil of hers."

"I guess I'll be going," said Gloria. "Some major or other from the office asked me."

Dorothy looked at her intently for just a second, the look of a person who is trying to decide whether or not to tell a woman that her lipstick is smeared, that an eyelash has fallen to her cheek, that her nose needs blowing. Finally she said: "Oh, really? What's his name?"

"Calloway. Why?"

"Oh, nothing. Just thought Davie or I might know him. We know scads of people in Special Services—I used to be USO, you know, and of course Davie is on the paper. Guess we don't."

"Guess not," said Gloria, wishing that Americans had a custom like bowing. It made difficult things like parting between two people who didn't like each other so much easier.

"Well, dear, I must run," said Dorothy, her eyes still intent on Gloria. "Perhaps I'll see you there tonight." She smiled briefly.

"Hope so," said Gloria and turned quickly away. She rather wanted to know just who Dorothy's officer was. In all likelihood someone she herself had known, would know, or was knowing. There were only so many officers. Well, bless the grapevine. She probably would know before the day was over. Really, Tokyo was Muncie all over again—such a small world after all. Muncie all over again, but different.

She drew a deep breath of the cool autumnal morning air and, for no reason, felt better. She breathed and smiled, realizing that, absurdly enough, she felt happy.

It was being in Japan that did it, she guessed. Here she seemed to weigh less, her body had a suppleness and dexterity that surprised her. The sun shone directly into her face, and she felt tall, beautiful, and altogether different from what she knew herself to be.

Often she had seen other Americans here smile for no apparent reason as they walked in the sunlight. Was it because they were conquerors? She doubted it. It was because they were free. Free from their families, their homes, their culture—free even from themselves. They had left one way of living behind them and did not find it necessary to learn another. Nothing they'd ever been taught could be used in understanding the Japanese, and most of them didn't want to anyway. It was too much fun being away from home, in a country famed for exoticism, in a city where every day was an adventure and you never knew what was going to happen tomorrow.

Actually, thought Gloria, there was something paradoxically reassuring about being in this country where the ground might shake at any moment, where the distant, snow-covered mountain might, for all one knew, blow the whole island to pieces. You could almost feel yourself living. At any moment the ground might crack beneath your feet and you'd find yourself face to face with eternity. It was quite different from safe, dull Muncie where habit very soon cut you from life, and Gloria was inclined to prefer Japan.

The gold-spotted leaves fell at her feet, and the cool air brushed her ankles. There was a clarity here—so different from the foggy, rainy island she had expected—a dryness, a precision in the atmosphere which made the most ordinary occurrence—a walk to the station for example—something joyous, as though a carnival were just around the corner.

There was another kind of clarity too. She felt herself a part of something larger, something benevolent, like god, engaged in kind works and noble edifices. And she could see enormous distances. Her own country—the United States, Indiana, Muncie—like an arranged vista, fell perfectly into place. She understood it; she understood her place in it and even that of her parents. It was as adorable as an illuminated Easter egg.

And here, all around her, was freedom, even license. The ruins were one huge playground where everything forbidden was now allowed and clandestine meetings were held under the noonday sun. The destruction, evident everywhere she looked, contributed to or perhaps caused this. She felt like a looter, outside society. Society no longer existed.

Here she was free, here in this destructive country where autos collided as though by clockwork, where sudden death was always a possibility, and where dogs went mad in the sun, casting their long, barking shadows behind them. More than at any other place she had been in her life, Gloria felt alive in Japan.

Two university students, black in their caps and high-collared uniforms, were walking toward her. They stopped talking to stare. When she passed them they both stood respectfully to one side of the sidewalk, their eyes never leaving her. As she walked beyond them she heard their conversation, suddenly animated, bright with words she would never understand. They were talking about her.

She turned to look behind her. Both of the students were walking backwards, gazing after her. Gloria read only appreciation in their faces. They saw her looking, blushed, and turned around.

Japan was like that. You could walk down the street and be admired. A visiting deity, deigning to step upon the common pavements. All the men would look at a white woman as though she were some rare, incalculably expensive and probably breakable object. At least, so Gloria believed.

She turned around again, but the students were gone. If she had smiled at them she might have assured for herself a kind of immortality. The handsome youngsters would reckon time from the day the American lady smiled at them. They would excitedly recall to each other just what she looked like; they would vie with each other in flattering descriptions. At least, so Gloria believed.

The next two men were middle-aged businessmen, and they didn't look at her at all. This did not disturb Gloria's illusion, however, for she considered them quite ugly. A man whom Gloria could not imagine as a bed companion simply didn't exist for her. But, in the next moment, a young carpenter on a bicycle turned to gaze so long that he almost ran into a taxi. Gloria turned around to look. Just to make sure he hadn't hurt himself. He was very handsome.

She realized she was smiling. Just before she passed through the Allied free entrance to the trains, she turned to look at the plaza before her, at the great city spreading beyond it. She saw the sedan and the driver still waiting back at the hotel, small and distant in the morning sun. He seemed to be looking at her. She couldn't remember whether he was good looking or not. Oh, well, it didn't make any difference. He seemed to touch his hat, but she couldn't be sure. It was this typical gesture which reminded her that he was Japanese. Really, Gloria, she giggled to herself, your standards are getting lower—or higher, as the case may be.

Still smiling, she nodded at the boy taking tickets at the wicket for Japanese and, feeling delightfully like Babylon herself, swept through the free Allied entrance to the trains.

When Tadashi first saw the tall American coming toward him in the fur coat he thought she must be his passenger. But then she and the shorter lady with her walked on toward Tokyo Station. Tadashi shifted his weight to the other leg and went on waiting. Straightening his cap, he watched the MP on duty at the billet entrance. The uniform was nice—sharp creases, boots like mirrors, immaculate gloves.

Tadashi remembered his own war-time uniform with something approaching nostalgia, then turned his own cap over one ear, slouched against the fender of the sedan, and deliberately scuffed his already broken and dusty boots on the tire. The military now sickened him as much as it had once attracted him.

He remembered when he had been a lieutenant. It had been the same then. Affection and loathing. He had both loved and despised the Army. Now that Japan had vowed never to fight again this was one responsibility that was no longer his.

But one less among so many didn't make much difference. There was his wife, his child, and the uncle who now lived with them. There was his job, so precious and so coveted by others that he had to fight daily for it. And there was his poverty—so extreme it seemed almost like a joke. He had never been poor before the war and now, after it, could scarcely remember being anything else.

He smiled reflectively. This was far different from the war days, when his sole responsibilities were toward Emperor and country. Those times had been holidays. Even in the face of certain destruction—perhaps because of it—he had felt it was eternally New Year's, a joyous time filled with gifts and pleasures, extraordinary occurrences and freedom.

Pulling a crushed Lucky Strike from his jacket pocket, he lighted it. It had been given him by his last passenger. Now he was dependent even for his few pleasures—and he saluted privates and corporals. At the Motor Pool he bowed to the lieutenant in charge.

He looked again at the trip ticket. His departure from the Pool was penciled in one corner, and when his passenger released him he was supposed to pencil in the hour and the minute. There was not supposed to be too much of an interval between the two.

Tadashi saw that the time of departure was seven-thirty, half an hour ago. If the lady didn't come soon, he would be in danger of a delinquency report. But if he went away without her and she made a complaint, that too might mean a report. Under the new officer a driver was discharged who accumulated three reports. He'd already gotten one, on the first day, because he'd stopped to watch a baseball game.

That was very typical of the military of any land. There was no consideration for the individual. He found it ironic that the American Army, enforcing democracy, should be so undemocratic. On the surface, of course, it made a great show of democracy, which had amazed the Japanese—the non-coms didn't slap their men around, and officers were actually seen talking affably with their subordinates—but basically it too was undemocratic. Any army was like this of course, but he had felt somehow that the American Army would be different. But it wasn't. Except that it would say that it would do one thing, for one reason, and would then do something entirely different, for another reason, whereas the Japanese Army had been almost monomaniacal in its adherence to established ways. But, whatever the difference in approach, all armies were alike in being convinced that the way they did things was absolutely the right way.

Such thoughts no longer disturbed Tadashi, for he was through with armies—forever. He might be forced to work for one, but he would not obey its rules. He would be a person and would triumph over it. His friends called this sentimentality, but that was what he believed.

He was nodding his head shortly and sagely in complete agreement with himself when he happened to see the fur-coated lady standing in front of the large entrance of Tokyo Station, outlined against the white sign of the Allied entrance. She appeared to be smiling at him—he couldn't be certain. But, just in case, he smiled and, standing up straight, touched his cap, though they were blocks from each other. There was nothing servile in his gesture, it was more a thank-you for the smile she'd given him earlier. She hesitated, then disappeared.

Perhaps she had been smiling at him, and perhaps she hadn't. At any rate, with the Americans there was always the possibility that they would, and this made him feel good. Americans were actually notoriously friendly when they let themselves be. Perhaps she was simply more friendly than most. It would be so nice being around them were it not for the military.

It wasn't specifically the American military that Tadashi hated; it was the military of all nations. He even had a theory about it. It was the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps of any nation that was responsible for that nation's difficulties. And they were so lethal that even owning one guaranteed trouble. If a country had an army, it was going to use it and could always find some excuse to do so. Japan was a perfect example.

Since the war Tadashi had become what his friends called a militant pacifist. This was very important to him, as important even as his job as sedan driver, for, in a way, his new ideas insured his dignity, his individuality—the latter concept was none the less precious to him because it was new—and made it possible for him to give a sort of allegiance to his job, if not to his uniformed bosses.

How ironically appropriate it had been that Japan should be destroyed by the forces she herself had used. The punishment had been terrible—and just. He was happy that there would never be another Japanese Army. The new Constitution had forbidden it. Maybe it was all General MacArthur's idea as they said, but it was the Japanese Constitution. And he—as valiant a crusader for peace as he had ever been for war—would never comply with the wishes of any army—American or otherwise.

Of course, this was all after the fact. For Japan had been destroyed—destroyed in that particularly terrifying, physical way that armies always choose. Perhaps it was the memory of the destruction that made his hatred of all armies burn as fiercely as had the fires of Tokyo. He could never forget it, and even now, years later, he relived it nightly.

He looked at the MP, at his own torn uniform, threw away the Lucky Strike butt, and again remembered what he could never forget—the destruction of Tokyo.

He remembered the day perfectly. It was in a cool, sunny, and unseasonably windy March. The children who had them still wore their furs. His two sisters, dressed alike in little fur hoods with cat's heads embroidered on them, were sent off to school, and his father went off to work next door at his lumberyard. His younger brother left for his classes at Chuo University, across the city, and he was left alone with his mother.

It was the third day of a leave from the Army. He had a new lieutenant's uniform. His mother wanted him to stay near home and call on the neighbors. He wanted to walk around the city and show off his new uniform. As she began the housework his mother smiled, told him to do what he wanted, and asked only that he come home early because his uncle was calling on them that evening. He told her he would, gave her a mock salute at the door, and went into the street.

Their home was in Fukagawa, which was like no place else in Tokyo. It had its own atmosphere, even as Ueno and Asakusa had theirs, but Fukagawa's was nicer, perhaps because it was not purely an amusement district. It hummed with industry; it was as though a carnival were continually in the streets. The carpenters pulled their saws, and the logs floated in the canals. The factories blew smoke to the sky, and the dye from the chemical plants made the canals green as leaves. The Chinese owned prosperous restaurants, and even the poor Koreans happily opened oysters all day long. It was the nicest part of the city.

He walked briskly, and by noon had been through all the main streets of his district. Now, having eaten three dishes of shaved ice, strawberry syrup on top, during the morning, he was ready for Tokyo's glittering center across the river, Ginza. It was time for lunch when he crossed the bridge to Nihombashi. He ate noodles at a little restaurant in the Shirokiya Department Store. Wanting to bring his mother a present, he selected a bolt of cloth—one of the more expensive cloths from under the counter, for the stock was small and consisted almost entirely of the war-time synthetics—and arranged to have it delivered to their home on the following day.

Then he went to see a movie. It was a war movie. Afterwards he walked past the Imperial Palace and took off his cap. Inside the outer moat it was cool under the pine trees, and he stood stiffly at the base of one, hoping a girl would sit nearby and think him handsome and soldierly in his cap and boots. But none did. Everyone was so busy. He'd never seen Tokyo so busy, and was pleased with the war which had given everyone his own higher duty.

After that he ate supper—he forgot where—and drank saké. Eventually he did find a woman, fashionably dressed but none the less available. They drank at a private table, and it was not until he heard the watchman making his rounds near Shimbashi Station that he realized it was ten o'clock and that he should have been home hours before.

But even then he did not leave. He could be home before eleven, and his uncle would be there at least until midnight. His father would be at one of the joro houses in the Susaki district and probably wouldn't be home until morning. So he decided to stay half an hour more, talking with the woman and enjoying her interest.

Later he was to think of the woman, whose name he could not remember having heard and whose face he had forgotten. She was dressed Western style, a rare thing during the war years, and was beautiful. And, had it not been for her, he would have been home, where he should have been and where, for many years afterward, he wished he had remained.

Some of Tokyo had already been bombed, but those few districts were far away, and the people in the rest of the city were not afraid. The radio said that the Americans dropped bombs indiscriminately and that there was no need to fear a mass attack, as the radar would detect the intruders and give ample time for escape. Just a year before, Fukagawa had been bombed, but the damage had been negligible. The bombs fell mostly into the country, and most people decided that the Americans were not very skilled in this important matter of bomb dropping. Fukagawa, near the country, had seemed as safe as Shimbashi, in the center of town.

Tadashi heard the watchman at eleven and was regretfully taking leave of the woman when the call of the watch was interrupted by the air-raid sirens. Earlier in the afternoon, while he had been in the movie, there had been an alert, but the all-clear had sounded immediately after.

Now Tadashi walked swiftly through the exit stiles of Shimbashi Station—secretly rejoicing that his uniform allowed it—and ran through the standing passengers, past the halted trains, to the top level of the building. He didn't really expect to see anything; he only wanted to be soldierly. This would impress the lovely lady.

He arrived at the top level just in time to see the sudden flair of massed incendiary bombs. It was Fukagawa. The planes were apparently traveling in a great circle. It was impossible to say how many there were, but it seemed hundreds. A great ring of fire was spreading. The planes were so low he couldn't see them and could tell where they had been only by the fires that sprang from the earth behind them. There was an enormous explosion, like August fireworks on the Sumida River, and a great ball of fire fell back on the district. A chemical plant had been hit. Minutes later, Tadashi felt the warm gust of air from the blast, miles away.