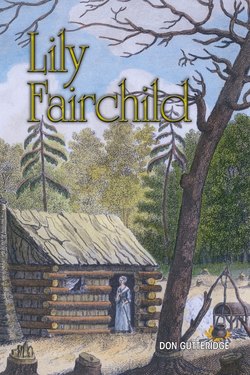

Читать книгу Lily Fairchild - Don Gutteridge - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеMoore Township, 1845

Something stirred in the darkness ahead. It made no sound, but it was present and alive. For as long as she could remember, she knew. The breath from a fawn’s cough could tease her skin – like this ripple of shaded wind against her cheek – long before her ear caught the sound and identified it.

Lily was glad to be in the comfort of the trees’ canopy. It was cozy here, like the cabin with Papa’s fire blazing, when Mama was not in her bed. Lily wasn’t afraid of the dark, though Mama sometimes shivered fearfully at night, especially those nights when Papa had “gone off” and Lily was beckoned to press her child’s body against her mother’s clenched form. She dreamt she was a moth spinning a warm cocoon around them both, full of charms to drive the uncertainty from Mama’s eyes. While outside, heard only by her, the snow sang to the wind and no one in the world was lonely.

It was never lonesome in the bush. Here living things emerged and endured in the dappled undergrowth – ferns and worts and fungi and mosses, and, in the few random spots freckled by sun, surprised violets. Lily could sense the creatures’ presence even as she took short quick steps towards the back bush, a place forbidden by Mama. She stopped to acknowledge them: a thrush untangled his song; a snakeskin combed the grass; a deermouse scuttled and froze.

“You stay away from the Indians, you hear?” Mama said so often. She seemed to hate them: they never did a lick of work; they drank whiskey, then went crazy and hurt people; they went hunting god-knows-where, taking good men with them, so the farms were neglected. And their women, they’re wicked too, and dance and do bad things…. Lily wanted to ask, not about the bad things, but about the dancing, though she never did.

Lily knew where the Indians lived. Many nights, curled in the straw of her loft, she heard the drumbeats come across the tree-tops from miles away and settle into their clearing as if aimed there. They were not like her soft heartbeat, nor like the sprightly songs Mama sang at her spinning wheel. Theirs was a pounding, repetitive music that set her heart ajar, that made her long to know what words could be sung to such a rhythm, what dances would find their feet in such a frenzy. She wanted to see those women, how they moved in the firelight that twisted above the black roof of the bush, what their eyes said when they danced in the smoky, burnished, mosquito-riven dark.

An axe rang against a tree-trunk, clear as a church bell. Papa’s back. Lily recognized the signature of his chopping: two vicious slashes, the second slightly more terrifying than the first, followed by two diminished, tentative “chunks.” Maybe Mama would hear them too and leave her sick bed. Papa was in the North Field; that was good. He’d only “gone off” as far as the Frenchman’s. Sometimes one of the LaRouche boys came back with him to help with the stumps or the burning. All three boys watched her with the edges of their eyes until Papa shouted at her to go away.

Papa had returned and that was enough to deter her from the bush and the forbidden terrain beyond the East Field, carefully planted now with wheat. She turned towards the North Field, five acres of newly cleared and fire-ravaged land where the Indians were not allowed to camp or hunt. Papa might be in a good mood. She listened carefully to the determined repetition of Papa’s axe against the grained flesh of the tree. He was at one of the hardwoods again. Abruptly the axe fell silent. Lily held her breath. Then she heard the thunderous, sustained shriek as a two-hundred-year-old walnut came crashing through the forest to stun the ground with its sudden goodbye. She paused and listened to the tree’s dying reverberate through the earth.

She would surprise Papa at his work, celebrate another tree felled, and laugh when he swept her up and twirled her around, saying . “Lady Fair Child, may I have the pleasure of this dance?”