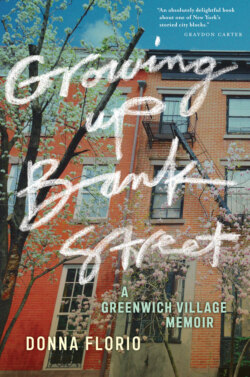

Читать книгу Growing Up Bank Street - Donna Florio - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 Six Blocks of America

ОглавлениеMosquitoes and Alexander Hamilton’s bank started the whole thing.

A lady scrambles across her muddy lane as wagonloads of panicked colonists from downtown crash by. She glares at the new Bank of New York mansion, an unwanted intruder in the peaceful woods of her sleepy 1798 Greenwich Village. That bank started it, she huffs. They want to escape their yellow fever quarantine, and now we have all the dirty downtowners moving here, bringing the disease to us.

A 1920s scientist strides towards his laboratory near the Hudson River, seeing nothing around him, his mind on his new idea for talking pictures. He passes John Dos Passos, sitting on the steps of his boardinghouse at 11 Bank Street. Dos Passos’s new novel, Manhattan Transfer, is attracting attention. Young socialite Marion Tanner, decades from stardom as Auntie Mame, hurries to the bootlegger across the street. She needs gin for the salons she holds in her elegant new brownstone.

In the 1930s, everyone broke because of the Great Depression, the poet Langston Hughes climbs the steps to his 23 Bank Street illustrator’s studio carrying his latest work. A block down, young John Kemmerer, an aspiring writer from Iowa, admires the pear trees and cityscape from the roof of his new building at 63 Bank Street. Three stories below John, the Swansons practice the tango for their vaudeville act at the Paramount Theater. Above the Swansons, Alice Zecher, newly arrived from California, winks at herself as she applies a bit of rouge for a job interview. Her plan is to be a secretary by day and a Village bohemian by night.

In 1942, a leader of the American Communist Party climbs the steps to his place at 63 Bank as FBI agents eye him from the Swansons’ windows.

In the 1950s, Tish Touchette, a female impersonator with a popular nightclub act, hangs his sequined gowns in his new place at 51 Bank and takes his poodle for a walk. He passes the actor Jack Gilford from number 75. Jack, blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee, the government agency that implemented the Red Scare tactics of Senator Joseph McCarthy, is desperate to line up a job—any job.

In the 1970s, when John Lennon and Yoko Ono don’t respond to their knocks, FBI agents push deportation orders under the door of their 105 Bank Street home. Photographers shove one other aside seeking shots of the corpse of Sid Vicious, the Sex Pistols bassist, who is being carried away after his overdose at 63 Bank Street.

Today, young transplants from California living in Sid’s former apartment pump their fists and high-five as their dream of establishing a taco stand in Chelsea Market comes true. Tish, now an elderly fixture on Bank Street, holds court on his stoop, talking about the 1969 Stonewall Inn uprising on nearby Christopher Street, the night that gay New Yorkers first fought for the right to socialize like anyone else. Down the street, film producer Harvey Weinstein, reputation and career in ruins, pushes through reporters on his townhouse steps.

That’s how I see Bank Street, my home in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, and its people. I was born here, arriving from the hospital in 1955 to 63 Bank Street, apartment 2B, next door to Mrs. Swanson, the vaudeville dancer. My small apartment has about 325 square feet. The layout resembles a barbell; bedroom on one end, living room on the other, with a narrow hallway in the middle. The front door opens onto the hall, off of which is a shallow coat closet, a galley kitchen, and a bathroom. The kitchen and bathroom each have a window, both facing the wall of a dark, shallow alley. The apartment doors are solid old wood with raised panels and brass keyhole locks. The living room has three windows, one facing the alley. The other two face Bank Street. One front window opens onto an iron fire escape, which has done duty as a drying rack, an herb garden, a place to set parakeet cages in the sun, and storage for party beer.

Walking back, away from Bank Street, you reach the bedroom. One bedroom window faces the end of the alley. Another looks out at a small carriage house and garden nestled behind the brownstone next door. The bedroom has a walk-in closet with an incongruous, fancy old window of its own. As a baby in a crib, I shared the bedroom with my parents. I threw toys at them when I was ready to be entertained, hastening their decision to give the bedroom to me, like many Village parents of the era, and sleep on a pull-out couch in the living room.

• • •

Elderly neighbors sat with my parents in shabby little Abingdon Square Park around the corner as I toddled in the sandbox. Some, like the journalist who had played chess with Mark Twain, had lived here since the early 1900s. The Bank Street of their youth had cast-iron gaslights and a stately band shell with marble columns. Icemen hawked thick blocks of ice coated in straw. Milk wagons rumbled over the cobblestones at dawn. Peddlers jingled bells as they wheeled hand-carts loaded with fruits and vegetables or offered to buy rags and scrap metal. Horse-drawn trolleys lurched along bustling West Fourth Street. Hand trucks with whetstones clanged, the owners seeking knives and scissors to sharpen. Street musicians performed under windows, hoping for coins tossed down by kind-hearted listeners.

As kids, some of those neighbors watched trees chopped down as 63 Bank, the only building ever to stand on this lot, went up in 1889, providing yet more cheap housing for the immigrants that were flooding turn-of-the-century New York.

Cheap or not, 63 Bank Street, five stories high and with three apartments per floor, had been built with a bit of style. Stubby marble columns rising above lion heads and wrought-iron fencing adorn the entrance while whimsical angels grin beneath the two front windows. Two painted wood doors with panes of beveled glass, flanked by lamps, open to the hallway as a gargoyle glares down from the ceiling. Small, festively patterned red, green, and orange tiles cover the floors. At the end of the front hall, a cast-iron stairwell with smooth wood banisters and gray marble steps leads upstairs, past hall windows that overlook the little garden next door.

A rope-and-pulley dumbwaiter once opened on each hall landing, making it possible to haul coal from the basement for heat braziers and cooking stoves. Rickety wooden steps led down to the basement from the back of the first floor hallway and, on the fifth floor, up to the roof. Cast-iron steps below the stone entrance still lead past the brick coal chute embedded in the sidewalk to the exterior door of the basement, a low-ceilinged maze with cast-iron pipes and wires overhead. In the back of the basement, a heavy metal door leads to a tiny cement backyard and side alley. Fire escapes run down the front and back of the building.

Inside our apartment, in 1889, privacy was nonexistent. Archways led from one dark, narrow room to another, arranged shotgun style. The kitchen, with its heavy cast-iron coal stove, sat at the back end. A privy toilet, off the kitchen, had an incongruously fancy window. Near one front window, a shallow brick alcove held a coal brazier for heat.

The 1920 census for 63 Bank Street reported a mix of Irish, Italian, Puerto Rican, and German tenants. They were shirt pressers, dockworkers, machinists, market workers, saleswomen, bank note printers, mailmen, and factory workers. Virtually everyone over eighteen went to work.

The Italian American family that bought the building in 1925 and still owns it upgraded the place in 1937. Cast-iron steam radiators replaced the coal braziers, and the shallow alcoves that held the braziers were cemented and plastered over. The kitchen of 2B became a bedroom and the privy toilet became the bedroom closet, fancy window and all. A galley kitchen with a gas stove, a ceramic double sink, and a wall of wood cabinets went into the middle of the apartment next to a new private bathroom, complete with “flushometer” and bathtub.

The improvements attracted college-educated John Kemmerer and artists like Mrs. Swanson, who moved in and stayed for the rest of their lives. But number 63 kept some of the old ways. When I was little, the milkman still clanked upstairs at dawn with his wooden basket of glass bottles, leaving ours by the door and taking away the empties. We didn’t use coal, but the hallway dumbwaiter was still used to collect the trash we put outside of our doors at night by the super who lived in the basement. It stayed in use until the late 1950s, when we kids played in it once too often.

My childhood neighbors were painters, social activists, writers, longshoremen, actors, postmen, musicians, trust-fund bohemians, and office workers. Some were born here; others came because our street let them live and think as they liked. I listened to debates on socialism, reincarnation, vegetarianism, and politics on stoops and in grocery stores.

I didn’t know that our ways had little to do with the rest of America. People lived as they pleased on Bank Street, and I, the offspring of free-spirited artists, thought nothing of it. Katherine Anthony, the elderly biographer at 23 Bank who introduced me to books like Johnny Tremain, had openly lived here with her female partner since 1912. They’d both had high-profile careers and raised their adopted children a century before gay marriage was legalized. The mixed-race couple in apartment 1C, whose son was eight when I was born, were just more 63 Bank grownups, frowning as I chained my bike to the hallway radiator. I didn’t know that they might well have been jailed or even killed had they lived elsewhere.

• • •

Bank Street is a six-block-long strip south of West Fourteenth Street that starts at Greenwich Avenue and ends at the Hudson River. In the 1950s and ’60s, as I looked left to Greenwich Avenue, I saw a gloomy side wall of the Loew’s Sheridan movie house, built in the 1920s, its gilded rococo splendors hidden inside. To the right I saw nineteenth-century tenements like my own building, a teacher-training school, a spice warehouse fragrant with aromas, a General Electric factory, and, further down, abandoned elevated railroad tracks crossing high above the street, past a hulking old science laboratory. The street ended at our rotting Hudson River pier.

In those years, as I walked and played from one end of Bank Street to the other, I passed through every social, cultural, and economic layer of American life. Bank Street put its wealthy best foot forward on the first block off Greenwich Avenue. This is where Harvey, a nuclear physicist, and his wife, Yeffe, an artist, lived at 11 Bank Street, in a brownstone with a front garden where Yeffe and I planted bulbs. Their neighbor at number 15 was my friend Jack, scion of a prominent German Jewish family. As I passed other townhouses on that block I saw crystal chandeliers and gleaming silver candlesticks through the windows.

One brownstone owner was Miss Clark, heiress to the Coats & Clark sewing thread fortune. Still others were actors like Alan Arkin and Theodore Bikel. Bikel, who painted his building blue in honor of the state of Israel, founded in 1948, nodded hello in his dressing gown as he collected his New York Times from the front steps. TV personality Charles Kuralt, of 34 Bank Street, was on CBS every week with his show On the Road with Charles Kuralt. He smiled at me as he passed, looking more like a junior-high-school gym teacher than a celebrated broadcaster.

Around the corner from Bank Street, on Greenwich Avenue, stood a row of small shops, including Heller’s Liquors, which had an imposing “Liquor Store” neon sign with a clock above the door. Mr. Heller was particularly proud of that sign because his father had scraped up the money to have it made back in the 1930s. Neatly stacked crates of wine covered the splintered wooden floor in one aisle, with liqueurs in another and hard liquor in a third. The counter was layered with customers’ postcards and family photos, including ours.

Next to Heller’s was the Casa Di Pre, a small restaurant with candles in Chianti bottles and soft peach walls. When the evening rush died down, the owner joined us for espresso, bringing sesame cookies, to chat about theater and opera. Next to Casa Di Pre, Saul and Min Feldman kept their five-and-dime notions store as they’d bought it from the 1920s owner. Worn wooden bins brimming with envelopes, packets of glitter, straws, bathing caps, shoe polish, sewing kits, and pink rubber Spaldeens filled the middle of the shop. If my parents and I didn’t find what we were looking for, Saul or Min rummaged through the drawers below the bins. We seldom left empty-handed.

On one corner of Bank and Greenwich Avenue stood a grocery store with green-and-white-striped awnings and signs advertising freshly butchered meat. I waited outside for my parents, looking anywhere but at the poor skinned lambs hanging on metal hooks in the window. The smell of blood and sawdust inside upset me too. On another corner stood an old pharmacy with marble counters and globes of colored liquids in ornate cast-iron fixtures hanging in the windows. The elderly counterman always put two maraschino cherries on my ice cream, winking at me as he did.

The Waverly Inn, at the corner of Bank and Waverly Place, now a glossy haunt for celebrities, was an inexpensive, casual place back then, with wooden benches, Dutch tiles framing small brick fireplaces, and an open-air garden behind a low stone wall. On summer evenings, my friends and I sometimes tiptoed down the sidewalk with water balloons, counted to three, and threw them into the garden, diving behind parked cars before the cooks ran, swearing, from the kitchen.

Down the street, on the corner of Bank and West Fourth Street, was the Shanvilla Market Grocer. In the early morning, Pat Mulligan, the white-haired Irish owner, put out baskets of lettuce, peppers, apples, and bananas. Chipped freezers with wheezing motors were stocked with eggs, milk, and cheese. Cans and boxes stacked the old wooden shelves, which Pat reached using a pole with a metal claw.

Next to Shanvilla was the venerable Marseilles French Bakery. Wicker baskets lined with waxed paper sat on shelves behind the old glass counters, holding fragrant baguettes, rolls, and thick loaves dotted with salt or sesame seeds, fresh from the ovens in the back. Marie, a thin Frenchwoman with no front teeth who lived down by the river, was usually behind the counter.

Mr. and Mrs. Lee operated their Lee Hand Laundry around the corner, next to a shoe repair shop and Mr. Helping Exterminator. I had a hard time understanding the Lees’ broken English, but they were smiling and polite behind their worn Formica counter. Paint peeled from the cracked plaster walls, bare except for photographs of their kids and curling Chinese good-luck signs and calendars. Cast-iron rods filled with shirts and pants on wire hangers stretched along the ceiling. The place smelled like steam and fresh fabric. The dented laundry scale squeaked. One day a kid wrote “No tickee, no shirtee” on a piece of paper and handed it to Mr. Lee, grinning and stretching her eyes to slants. When my father yelled at her, she stuck out her tongue at him and ran off.

• • •

My block, between West Fourth and Bleecker Streets, had a few elegant brownstones, but it had tenements and factories too, making it more of a mix than the block between West Fourth Street and Greenwich Avenue. The stoop at 51 Bank Street, a grayish brick walk-up apartment building on the corner of West Fourth Street, was an informal old men’s club. Club regulars included Tom, an elderly Italian who drove a small, battered gray truck with the words “Tom’s Ice” written on the sides in big black letters. I sometimes saw Tom, wearing cracked leather gloves, pull out blocks of ice with metal tongs and carry them into Shanvilla’s basement or the fish store around the corner. We had an electric refrigerator and so did everyone else I knew. I’d never seen an icebox, the wooden kind that everyone, my parents told me, used when they were kids. Icemen like Tom were becoming things of the past, they said, and I worried that Tom would soon be out of a job.

Tom and other grizzled Bank Street men leaned against number 51’s concrete stoop, passing the time. Regulars included Joe, a retired dockworker, and Mr. Hanks, who had been a fireman. They nodded to their neighbor, Tish, the nightclub performer, but rolled their eyes behind his back as he walked away. The commercial space on that corner was a tie-dyed clothing store in the 1960s and later a vegetarian restaurant. The old men disapproved of both businesses. Those dirty hippies do drugs, they fumed to my father. The old men didn’t want us bothering them, so they’d shoo us down to play spots like in front of the wallpaper factory at 59 Bank.

Since most Village kids under ten weren’t allowed off their block, after-school play groups were arbitrarily defined by address. We got excited when coal trucks pulled up to deliver their wares or when horse-mounted police officers rode by from the stable a few blocks away. We’d pet the horses, and sometimes I’d ask if I could sit on one, but the policeman always said no.

We were careful in front of 60 Bank Street because little Josh lived there. Although Josh was wasting away from an illness that eventually killed him, he usually wanted to join us. His parents looked sad when they had to say no, which was most of the time. We tried to make it up to Josh, making him the referee if he was watching when we played tag or statues. He’d squeak “You’re out!” in his tinny voice, perched in his window, pointing to the jail garden below his window.

On his rare good days Josh was allowed out for a little while, his eyes bright with excitement. He was bald and as tiny-boned as a bird. I let him grip my arm, carefully swinging him in circles while his parents smiled anxiously, trying not to hover. Rudy let Josh pummel him to the ground with his little fists. Ginny sat him on her bike and delicately wheeled him to the corner and back. One day a folk singer with a guitar came along and sang with us below Josh’s window. The singer had only one leg. He said he’d lost the other one in a place called Vietnam. When Josh died, we sat on his steps. His parents came out and we cried together.

Number 69 Bank Street housed the Bank Street College of Education, located there from 1930 until it moved uptown in 1971. The building had originally been a yeast factory, and its wide sidewalk was the best Double Dutch jump rope spot. Student teachers wearing peasant blouses and dirndl skirts climbed the steps, smiling at us.

Number 68 Bank Street, across the street from my building, was a boarding house. Bill, a burly retired truck driver who lived there, often sat on his stoop reading his Daily News. Bill and I watched, smiling, as city workers planted trees up and down Bank Street in 1962. He watered the delicate young honey locust in front of his place every day and grew irritated when people let their dogs pee on it. Finally, out of patience, Bill armed himself with a box of mothballs, and when dogs paused to sniff at the tree’s roots, he’d grab a handful and let fly. Dogs yelped and owners cussed, but Bill’s tree grew and still presides over the building.

Number 75 Bank Street, on the corner of Bleecker Street, was our block’s grandest apartment building, the one with an elevator. Gardens lined the entrance, and a doorman manned the Art Deco lobby. We liked to shimmy up the wrought-iron gate in front of number 75’s side alley. It was a daring climb since we had to watch out for Suzy, the live-in super’s boxer. If she heard us, she ran up, barking and snapping as we frantically slid down, fingernails scratching the glossy black paint. The alley was an enticing space and we wanted to play in it, but the gate was always locked and we were too afraid of Suzy, although nobody would admit it.

Number 78–80 Bank, the big tenement building on the opposite corner of Bank and Bleecker Streets, was home to tough, older teenagers back in the early 1960s. Girls wearing white or pale pink lipstick sat on the stoop snapping gum and teasing their hair into bouffant towers. Boys with slicked-back hair and black leather jackets nuzzled them, sliding their hands around until the girls slapped their wrists. They lit cigarettes in front of adults, which astounded me, casually flicking butts into the street with a bored flip of the finger. One of the girls bolted to my side when a disheveled man waved an address on a slip of paper and asked me to go into a hallway and help him read it. “Get atta heah, ya dirty creep! Kid, nevah, evah go wit’ one of them pervies! He’ll do nasty to yah!” I had no idea what she meant.

By 1969 the greasers were gone. I was 13, and I babysat there for a divorced mother who had moved from New Jersey to be a hippie. She was an affectionate mom but rarely cleaned the house. Rolling papers sat on a shelf above the dirty kitchen sink. Even though I searched diligently, I couldn’t find her dope stash. One day I couldn’t stand the mess anymore and cleaned it myself. The children’s dad, who still had a crew cut and wore skinny black ties, beamed when he came to the city to pick them up. “This looks great!” he said. His face fell when I told him that I had done it.

Weekend hippies were obvious; carefully beaded, asking directions to Washington Square Park in the 1960s and ’70s. If I was in a nasty mood, I either sent them uptown to Chelsea, then a boring slum unless girl gangs from the projects were chasing me as I ran to and from my junior high school, or down to the rotting Hudson River docks. Maybe, I snipped, they’d try to blend in at the Anvil, a longshoremen’s bar by day and a gay, druggy sex club by night: all customers serviced by roving hustlers and prostitutes.

Until the mid-1960s, a hulking spice warehouse sat on the corner of Bank and Bleecker Streets, wafting a delicious orangey aroma through the streets on warm days. A white Greek temple sat by itself in the middle of Hudson Street, opposite the warehouse. I thought the temple was an image from a childhood dream until I saw archival photographs of the city in my twenties. My temple was there, a hexagonal bandstand from the 1880s, its second story framed by fluted marble columns. By the 1940s, an older Villager told me, bums slept in it and kids set fires there. It was demolished in the late 1950s.

A few years later the warehouse was knocked down too, and a new playground went up over both sites. Whoever designed that park either didn’t know kids or had it in for them. It had lunacies like a fifteen-foot concrete column with a climbing ladder, topped with a platform, set invitingly next to a sandbox. Luckily I’d just turned ten, a magic age when my parents decided that I was streetwise enough to play in other parts of the Village. I scorned the new kiddie park and met my friends in rowdy Washington Square Park. One kid, still grounded on Bank Street, jumped off the platform and broke his leg. Parents rushed kids to emergency rooms and yelled at politicians. Eventually the column was torn down.

I could also, at ten, walk down the other four blocks of Bank Street to the end, at the Hudson River. There weren’t many attractions. The Westinghouse Electric factory that took up an entire block was still open, although after a fire in the 1960s the factory closed and the building became a doorman co-op. Locals snickered at the idea of fancy living in an old factory.

I kept exploring, savoring my independence, passing the factory and walking towards the river, past dilapidated bars, the sour smell of stale beer wafting onto the sidewalk. Our block was tarred, but lumpy Colonial-era cobblestones on those last blocks made for a roller-coaster ride and still do. My father cursed and gripped the wheel as our Plymouth Valiant bumped and lurched.

The block between Greenwich Street and Washington Street was a mix of boxy 1950s brick apartment buildings, 1800s tenements, and small, run-down houses, with a few fine exceptions tossed in. My friend Billy Joyce, a live-in butler for Alwin Nikolais and Murray Louis, the renowned dance couple who owned number 113–115, sunned himself in a beach chair in front of their house and chatted with passersby. Opposite Billy stood HB Acting Studio’s three adjoining buildings. Young actors hung around the front, practicing lines, oblivious to the tenement dwellers who lounged in their doorways, drinking beer.

By the time I reached our last block, in 1966, the one that ran to our Hudson River dock, I was in a completely different Bank Street, many social classes removed from the wealthy brownstones at the other end. This block reflected the sad changes that were going on throughout New York City in the mid- to late 1960s. Middle-class families were fleeing to the suburbs. We’d lost the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Brooklyn Navy Yard shut down, taking with it thousands of jobs. A garbage workers’ strike left rotting bags, thrashing with rats, on the streets for nine days. Prostitutes and strip joints took over Times Square. The city’s crime rate soared.

The traditional longshoreman jobs of the Hudson River piers, once crowded with passenger and cargo ships, were drying up as airplanes took over the transport industry. Those jobs had been the livelihood of many Bank Street families for generations. A hulking cluster of dark, deserted buildings, which had been a famous Bell Telephone research laboratory for a hundred years until it closed in 1966, loomed over one side of our last block. Decayed tenements and boarded-up shops leaned like rotted teeth on the other. One grocery store was all that was left of the small shops that had once flourished by the river. Furtive, hard-faced men lounged against peeling billboards advertising 7 Up and Pall Malls. Heroin addicts swayed slowly in doorways, their limbs twitching.

An abandoned elevated railroad track ran through the Bell Lab building, continuing south on rusty iron pillars along Washington Street. A second derelict elevated track darkened the air along West Street, letting small pockets of dirty dusty sunlight filter down to the sidewalk. Packs of shrill hookers—male, female, and I wasn’t sure—swarmed passersby and cars, leading johns to unlocked trucks or the pier. Trolley tracks ran next to the river, but by then there hadn’t been any trolleys for decades. Except for the grocery store, the only business still open down there then was a prison. Dad, who spent hours looking for parking spots near our apartment, wouldn’t even slow down on that block, let alone park there.

We still had a pier, although it wasn’t a smart place to play. Even if I didn’t fall through the broken planks or drive a rusty nail through my foot, being there during the week, at any time of day or night, was usually asking for a mugging in the 1960s and ’70s. I kicked a junkie who tried to pull my bike from underneath me, but had no answer when one of the watching hookers said to me, “Well, what the hell do you think this is? Central Park? Go play somewhere else.” She was right.

By fourteen I’d learned how to handle blocks like this one. I’d walk down the middle of the cobblestones, stepping aside for passing cars, so shifty guys couldn’t grab me and drag me into an empty hallway. A nodding heroin junkie was a harmless obstacle to avoid. Roaches ran down the grocery store’s walls. I bought my Hostess cupcakes elsewhere.

I needed those new street smarts. My girlfriends and I were hitting puberty, and our young breasts and hips suddenly made us walking targets. Men shouted from cars, licking their lips, or blocked us on the sidewalk. One jazz musician mother, realizing that we’d caught on to her recipe, now boiled chamomile instead of marijuana to make tummy tea for our new ailment, menstrual cramps.

The rotting Bank Street pier changed completely on summer weekends in the late 1960s and ’70s. It became a noisy, laughing party, packed with gay men reclining on beach towels, rubbing baby oil on their sculpted bodies. My girlfriends and I quickly learned that the men were safe to be around and far more fun to boot. We joined them, pulling down the shoulder straps of our bikinis and gossiping, playing our transistor radios in peace.

• • •

Bank Street had its share of grumps and jerks, but many others were wonderful. Sabine, the artist who lived in 5C of our building, collected money and furniture for our teenaged black super and his pregnant wife, recent arrivals from rural Mississippi, who were too poor to furnish their basement apartment or pay for prenatal care.

When they moved to a bigger building, we got feisty little Ramiro, a retired merchant marine who could fix any leaky pipe or worn lock and kept the halls hospital clean. As my grandmother in apartment 1A started weakening with what eventually turned out to be brain cancer, Ramiro looked in on her several times a day. When I stayed with Grandma, I did homework with cotton in my ears as the primal therapy group next door in 65 Bank screamed themselves to release. Blocked chakras sometimes kept them howling long after New York’s 10 p.m. quiet curfew. Ramiro, obscenely fluent in several languages, reserved some of his best cursing for them.

Charles Kuralt traveled the country doing his On the Road TV shows, which profiled Americans from all walks of life with respect and dignity. Marion “Auntie Mame” Tanner broke the locks on her brownstone doors so that anyone who needed shelter could walk in at any time. Lawyer/politician Bella Abzug of 37 Bank Street spent a night hiding from the Ku Klux Klan in a Mississippi bus stop bathroom to plead with the state’s governor to spare the life of a black inmate on death row.

In college, I thought about the many artists and social idealists on my street who rejected day jobs. If they’d come from money, or married a worker bee, like Roger, the artist whose wife was a secretary, they got to pursue their passions full time. If not, they scraped by, waiting tables or driving cabs and their older years often brought hard choices between buying food and paying the rent. Their plight was what made me grit my teeth, bypass the writing and philosophy departments I longed to join, and endure boring education courses until I got teaching degrees and grimly took a job in a New York City public school.

I didn’t have the self-confidence to chase my artistic dreams like they did. Plodding on, I ignored my doubts and married my high-school sweetheart at a ridiculously immature twenty-four years old because it seemed inevitable. My parents were moving out, and we took their 2B apartment. As teenagers we’d been crazy stupid in love, but we’d already grown apart. Bank Street life together became a jail for some crime we’d unknowingly committed.

When we divorced two years later, I used the teaching degrees and fled, taking a job in a Thai university in the 1980s while a musician friend sublet the apartment. Although I was never going to fall in love again, I eventually did, this time with a Thai-born Dane, a Thai TV celebrity. I spent six magical years as a TV producer expatriate with a teak house, mango trees in the lush garden, and live-in servants. I thought I was done with Bank Street, but the magic died when his hidden alcoholism resurfaced and wrecked our lives. I flew home, crying, to divorce a second time and be a New Yorker again. Teaching again was the fast solution and it worked. I had friends, traveled for months every summer, and even touched some kids’ lives. I got an administrative degree. Life on Bank Street was OK.

Still later, on 9/11, when I’d been at work in a small downtown school with devastatingly clear views of the World Trade Center towers, Bank Street became both refuge and mental ward. I fought to regain my sanity, screaming myself awake over and over as the victims I’d seen clawed at my windows, pleading for rescue. Bank Streeters and Village friends saved me with meals, walks to doctors, and soothing words when I panicked, sure every time I heard a siren wail that another attack was underway.

For many years after that I shared the apartment with my late husband Richard, in a wholly unexpected later-life marriage. We met when a mutual friend asked me to help Richard, who had been practicing medicine in Africa, find a New York apartment. We kayaked and grew vegetables at our weekend place and trekked through foreign countries. Children, we agreed, might have been wonderful, but we weren’t together when that might have happened and that’s OK.

And I still have Bank Street, past, present, and future.