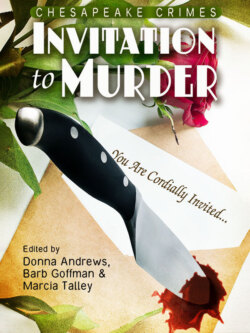

Читать книгу Chesapeake Crimes: Invitation to Murder - Donna Andrews - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SECRETS TO THE GRAVE, by K.M. Rockwood

ОглавлениеMiss Grayling stared at the envelope on the kitchen table, a proper envelope, made of heavy bond ecru paper, addressed to her in a fine hand. It appeared to be an invitation or an announcement of some sort. Miss Grayling had not received a formal piece of correspondence in several years. More than years, several decades, perhaps.

The envelope had arrived with the Monday morning mail. A notice from the electric company about a planned service outage. An advertising circular from an unfamiliar store. A notice from the city that the tedious work on the sewer system, which had the lawn and sidewalks torn up, would continue for several weeks beyond its original scheduled completion date. These she ignored.

She turned the envelope over. As was customary in her youth, the return address was printed on the back flap: Mrs. Howard Bellingsworth, it read, two streets over. No zip code.

Was that Julia Crumwell Bellingsworth, whose husband had passed away at least twenty years before? As girls in Middle Falls, they had never been friendly, Miss Grayling being somewhat older and of superior social standing. After Julia’s marriage to Howard Bellingsworth, however, they had traveled in the same social circles. Many were the teas, receptions, and card games which they had both attended.

But that had been years ago. Few of those ladies were still around. Certainly Miss Grayling had not heard from any of them recently. Even the funerals, which she felt obliged to attend and were often followed by quite tolerable luncheons, seemed to have ceased.

So why this missive?

She would have to open it.

Such elegant stationery demanded a proper letter opener, not the kitchen knife Miss Grayling used for most of her mail. She picked up the envelope and headed for her late father’s office. Surely there would be a letter opener in his rolltop desk.

She had forgotten that the office was in need of repair. A gun rack and a mounted moose head lay on the floor. Holes gaped in the wall where they had once been fastened. Cracks ran down the walls. The curtains were drawn, but she could see dust motes floating in the air. She sneezed. Perhaps it was time to clean this room. Wash the curtains. Dust the furniture and the baseboards. Take down the teardrops on the crystal chandelier and dip them in a vinegar solution. But that would require climbing a stepladder, something Miss Grayling had done often in her life yet which now seemed unacceptably dangerous.

But those were issues for another day. She opened the top drawer of the desk and extracted an ivory letter opener. Carefully, she ran it under the flap of the envelope and sliced it open.

A folded correspondence card of the same heavy ecru paper was inside. She slipped it out. The front bore embossed initials: JCB. Undoubtedly Julia Crumwell Bellingsworth.

Curious, she opened the card.

As she suspected, it was an invitation. An invitation to tea. On Thursday at three o’clock in the afternoon.

Should Miss Grayling go? What future social obligations would she incur if she accepted? Her first inclination was to send a gracious refusal.

On the other hand, it had been so long—years—since she had been invited anywhere. The worst she could envision was an obligation to reciprocate with another tea. She had the accoutrements required—a silver tea service and spoons, fine china cups and saucers, Irish linen tea napkins embroidered with an elegant “G.” All that remained would be the necessity to make some scones, a few sandwiches, and tiny cakes.

Or perhaps she could purchase them. Along with some excellent tea. Miss Grayling would have no problem doing that.

Curiously, there was no R.S.V.P. on the invitation. A bit presumptuous, surely, for Mrs. Bellingsworth to assume she would come if invited. Still, if Miss Grayling were unable to go, she would need to send regrets. One did not let people plan an afternoon tea if one had decided not to attend.

She would go.

* * * *

Thursday afternoon was dark and rainy. Miss Grayling wore her green woolen suit with the short tailored jacket. She believed in buying quality, classic clothing. Fashions come and go, hemlines rise and fall, but this suit was always in good taste. She checked her hat in the mirror, adjusted its feather to a more jaunty angle.

She frowned. When had her hair, always fine, become so wispy? When had it lost its color so completely, appearing translucent?

No time to be concerned about that now. She picked up her purse, gloves, and umbrella, and headed out her front door.

For several days, uncouth workmen had been laboring in front of the house and in the side yard, digging a massive trench, pulling up sections of old clay pipe. Today they were nowhere to be seen. The trench was still there, covered by a tarpaulin. Perhaps the inclement weather precluded the possibility of outdoor work.

A section of the sidewalk had been left intact, flanked on either side by crude barriers. Miss Grayling stepped carefully while unfurling her umbrella.

So much of the sidewalk had been torn up that Miss Grayling was sometimes forced to walk in the street. She tried to avoid stepping in puddles and muddying her shoes. They, too, were of classic design, laced black shoes of fine leather with sturdy two-inch heels.

Mrs. Bellingsworth’s house, similar to Miss Grayling’s own, was an ornate Victorian with stained-glass windows, festooned with gingerbread and covered with white clapboard siding. On the front porch, Miss Grayling shook off the drops of water and carefully furled her umbrella and fastened the strap around it before ringing the doorbell.

The door was opened by a maid in uniform, who relieved Miss Grayling of her umbrella and stepped aside so Miss Grayling could enter.

Miss Grayling’s family had employed housemaids when she was young. There had been a nursemaid whose job it was to see to the children’s welfare until they were old enough to leave home. Her brothers went off to boarding school. Miss Grayling herself never left, so the nursemaid eventually gave way to a governess, who finally moved on, too.

Who had maids nowadays? Obviously, Mrs. Bellingsworth did.

The well-lit entry way was every bit as grand as Miss Grayling remembered. No floating dust motes or faded carpet here. But now there was a chairlift snaking up the rail that curled along the staircase.

“Good afternoon, Miss Grayling.” The maid gave a little curtsy. She indicated the entry to the parlor. “Please be seated. Mrs. Bellingsworth will join you shortly.”

What kind of a greeting was that? Miss Grayling was responding to an invitation, not calling unexpectedly. Was she to wait for her hostess to appear? Most unseemly. Perhaps Mrs. Bellingsworth was making a statement about whose time was more valuable? She was tempted to reclaim her umbrella and leave.

Then again, the delay could be inadvertent. Miss Grayling recalled the chairlift. Perhaps Mrs. Bellingsworth suffered from physical infirmities that did not respond to a convenient schedule.

Still, she could have been offered refreshment while she waited.

As the minutes ticked by—fifteen of them according to the clock on the mantel over the blazing gas fireplace—Miss Grayling began to worry if she had misread the time on the invitation, or mistaken the day.

Just as she was about to summon the maid, a door opened and a woman in a wheelchair rolled through.

Could this be Mrs. Bellingsworth? She looked so old! It had been years since they had seen one another. Miss Grayling was pleased that she herself had not aged so.

“Good afternoon.” Mrs. Bellingsworth raised a lace-trimmed handkerchief to her mouth and coughed lightly. “I am delighted that you were able to make it this afternoon.”

Miss Grayling sat stiffly. “Good afternoon. Thank you for the invitation.”

“Ah, I do love a good, proper tea, don’t you?” Mrs. Bellingsworth took a small bell from among her skirts and rang it gently.

A pocket door slid open and the maid stepped through.

“You may serve tea now, Beatrice,” Mrs. Bellingsworth said.

The maid nodded and withdrew, reappearing a few seconds later pushing an elaborate tea cart.

“Please pour, Beatrice.” She turned to Miss Grayling. “I’m afraid my arthritic hands make some tasks difficult.”

The maid proceeded to pour a cup of tea, add milk, and pass the cup and saucer to Mrs. Bellingsworth, who took a sip and placed it on a small side table.

Didn’t Beatrice realize that guests should be served first, and that no one should taste the tea until everyone had been served?

Mrs. Bellingsworth gave no indication that she was aware of such niceties.

Beatrice poured another cup and looked at Miss Grayling. “Milk?” she inquired.

“No, thank you. Have you any lemon?” Miss Grayling asked.

“I’m sorry, no,” Beatrice said, not looking in the least bit sorry. “Sugar?”

“Yes, please.”

Beatrice lifted the lid off the sugar bowl and reached for the sugar tongs. “One lump or two?”

“Two, please.”

The maid drew out a misshapen lump of sugar and dropped it into Miss Grayling’s tea. When she attempted to extract a second lump the tongs slipped. The rest of the sugar appeared to have solidified. Beatrice pried at it, then hammered it with a side of the tongs.

“One is plenty,” Miss Grayling assured her, wondering how long it had been since anyone had asked for sugar.

Beatrice handed her the cup and picked up a plate of sandwiches, which she offered first to Mrs. Bellingsworth, who selected two.

Hostess before guest? Most unconventional!

Ignoring Miss Grayling, Beatrice set the plate down on the cart and reached for a plate of frosted tea cakes.

Once again, she offered the plate to Mrs. Bellingsworth, then placed the tea cakes on the cart. She backed up a step, her hands folded behind her.

This was too much for Miss Grayling. “May I have a sandwich, please?”

Beatrice didn’t move, but her eyes flickered over to Mrs. Bellingsworth, who nodded. “But of course! Beatrice, pass the sandwiches to our guest.”

Miss Grayling selected a single cucumber sandwich. What a strange affair this was turning out to be.

The ladies sipped their tea in silence.

Finally Mrs. Bellingsworth turned to Beatrice. “I know you have family matters to attend to, Beatrice. Go home now. You may clean up in the morning.”

“Yes, ma’am. Thank you, ma’am.” Beatrice gave a half curtsy, turned, and fled through the pocket door.

Mrs. Bellingsworth watched her go, then put her cup down firmly in its saucer. “Now, Miss Grayling, perhaps we can get down to business.”

“Oh?” Miss Grayling was not aware of any business to which they needed to attend.

“Perhaps you are aware that I follow closely what is happening in our neighborhood. I have done so for many years.”

“Indeed?” Miss Grayling was not aware of any such thing.

“Oh, yes. Often I acquire bits of information that I don’t use at the time, but I keep them in mind. As a matter of fact, I keep notes. Dates, newspaper articles, scraps of conversation. I file them away. I have several file cabinets full, in fact. People have secrets, you know.”

What a busybody! Miss Grayling wondered what Mrs. Bellingsworth had in the files about her family, most of whom were deceased.

Except for her nephew Jarrett, who was—what was the word they used nowadays? Not queer. Gay? That was it. Miss Grayling understood that such an aspect of one’s private life was no longer considered shameful. Besides, Jarrett had never kept his sexuality a secret, living openly with that flamboyant art critic in New York City the way he did.

Whatever could Mrs. Bellingsworth be talking about?

“You see, Miss Grayling.” Mrs. Bellingsworth lifted one of the tea cakes from the plate and smoothed the icing with her finger. “What with the new sewer pipes being laid, quite a bit of excavation has been done. Much of it in your yard. You’d be amazed at the things those backhoes can uncover.”

Miss Grayling narrowed her eyes and glared at her hostess. “The excavator turns up rocks and soil. Clay drainpipes too, which get broken in the process.”

“Of course rocks and soil and broken pipes. But you know, many people bury the oddest things in their yards. Things they never expect to be unearthed.”

“Oh?” Was Mrs. Bellingsworth referring to something in her yard? Surely not.

Miss Grayling cast her mind back. What could it be?

“If only they knew where to dig,” Mrs. Bellingsworth said, licking frosting from her fingers.

The sandwich turned to paste in Miss Grayling’s mouth. She swallowed hard. “Exactly what are you implying, Mrs. Bellingsworth?”

Her hostess smiled slyly. “Your cousin came to spend the winter, as I recall. A tiny little thing, wasn’t she? Plump and rather sickly.” She took another sip of tea, studying Miss Grayling over the rim of her cup. “Now what was her name?”

“Mildred,” Miss Grayling supplied, casting her mind back six decades. Poor Mildred cried a lot, Miss Grayling recalled, and seldom ventured outside. As the days passed and the unhappy girl grew even plumper, Mildred had hidden away in her room, too embarrassed even to come downstairs.

One spring evening Doctor Fitzhugh was called to the house. As soon as he arrived, twelve-year-old Miss Grayling was banished to her room, but early the following morning, awakened by her father’s voice wafting up from the foyer, she arose and padded barefoot down the hall. Peering over the bannister she heard the doctor say, “Stillborn, way before its time. But perhaps for the best.”

Her father placed a hand on the doctor’s shoulder. “We’ll say no more about this, shall we, Fitz?” In his other hand he held a narrow white envelope.

Dr. Fitzhugh tucked the envelope into his inside breast pocket. “Most unfortunate, indeed. You will see to the disposal of the remains?”

Miss Grayling’s father nodded. “Leave everything to me.”

Miss Grayling later realized that Mildred had been pregnant. Now she worried that her father might have buried the baby in the side yard where its tiny bones had been uncovered by the construction crew.

Nonsense, she chided herself silently. If the workmen had uncovered a body, the police would already be investigating. Besides, the tragedy was an old one. Her mother, her father, cousin Mildred, and the doctor: none of the people involved were still alive. So why would Mrs. Bellingsworth think this would matter to Miss Grayling?

As if reading her thoughts, Mrs. Bellingsworth said, “You never married, did you, Miss Grayling?”

Miss Grayling had to admit that she hadn’t.

“I always found that strange. You had so many suitors in high school.”

Miss Grayling’s teacup rattled in its saucer. Was Mrs. Bellingsworth implying that Miss Grayling herself had given birth to the unfortunate baby?

Thinking about the way babies were conceived, not to mention born, Miss Grayling shifted uncomfortably in her seat. She had no first-hand knowledge of the process, of course, but still…

Mrs. Bellingsworth sat in her wheelchair, like a spider watching an innocent insect approach her web. “Perhaps it would be worth something to you to keep the situation private, Miss Grayling. I’m sure we could arrange to do that, for a certain, shall we say, fee.” She eyed the tiny cake and popped it into her mouth whole.

“Blackmail?” Miss Grayling was horrified. She wanted to stomp out of the house, but her legs felt paralyzed.

“Blackmail is such an ugly word, don’t you think?” Mrs. Bellingsworth leaned back in the wheelchair. “I prefer to call it small compensation for my discretion.”

“Small compensation!”

“Shall we say—five thousand dollars a month?”

“Five thousand dollars a month!”

“To one of your apparent means, that should be quite affordable. Of course, if I have miscalculated, and that is beyond what you feel you can afford, we can negotiate.”

“Negotiate!” Miss Grayling seemed to have lost her power of speech beyond inanely echoing Mrs. Bellingsworth’s ludicrous words.

“I have no desire to leave you penniless. If you bring a copy of your income tax return to me next week, we can go over it. Should five thousand dollars prove too much, we could settle for, say, sixty-five percent of your income. Most people would consider that a bargain.”

At last Miss Grayling was able to force herself to her feet. “I will see myself out, Mrs. Bellingsworth. Good day.”

Mrs. Bellingsworth chuckled. “Think about my offer, Miss Grayling! I am sure you wouldn’t want the entire world to know what you’ve kept hidden for so long. Come back next week at the same time, and we will resume our discussions. In the meantime, give some thought to what I have said. A small price to pay for peace of mind.”

Holding her head high and her back stiff, Miss Grayling marched to the front door. She retrieved her umbrella, opened the door, stepped out, and closed the door smartly behind herself.

Blackmail! This was unconscionable. Miss Grayling would not permit herself to be victimized in such a tawdry manner.

Could she even afford five thousand dollars a month? Her father had long ago arranged for an accounting firm to pay her bills and forward money to her on a monthly basis. Miss Grayling withdrew only enough to cover her expenses. Much of that money still sat accumulating interest in the bank.

That, however, was not the point. One simply did not dabble in blackmail, either as the instigator or the target.

At home, Miss Grayling was too upset to even think about supper. She fed her cat and made a cup of tea, which grew cold in its cup.

Tea! Mrs. Bellingsworth had used a courteous invitation as a means of perpetrating an indignity.

This outrage could not go unaddressed. Miss Grayling would have to do something about it. She knew she couldn’t sleep until she figured out what.

As the evening wore on, the wind died down, the rain turned to a steady drizzle, and Miss Grayling made her plans. She changed into the trousers she wore for gardening and pulled on her rubber boots. Was her old raincoat up to the task of shielding her from the wet and cold? Perhaps not, but she would make do. A scarf wrapped around her neck would help. She took two flashlights, one big and one small, and a small sharp knife. She tucked several pairs of the rubber gloves she used to protect her hands when she washed dishes into her pocket. From a hook in the pantry, she lifted a large ring of skeleton keys. Miss Grayling had no idea what most of them unlocked, but she remembered the old caretaker carrying them on his belt until he died.

After turning off all the lights except for a dim one in kitchen, she stepped out onto the back porch into the pitch-dark night.

As soon as she rounded the side of her house, though, the streetlights provided sufficient illumination for her to proceed if she was careful. Since the last thing she wanted to do was call attention to herself, she kept the flashlights in her pocket. Stepping carefully, she made her way around the trenches.

Keeping to the side of the street away from the streetlights and staying in the shadows as much as possible, Miss Grayling walked the several blocks to Mrs. Bellingsworth’s house.

Most of the houses along the way were dark. Here and there a porch light shone or a light blazed in an upstairs window.

Did anyone in the neighborhood have security cameras? Deplorable things, recording whatever went on in their view, stripping innocent passersby of their privacy. But even if one were trained on her now, Miss Grayling doubted she would be recognized in the darkness.

Mrs. Bellingsworth’s Victorian house had many outcroppings and angles that cast even darker shadows. Not to mention overgrown shrubbery.

Keeping her head low, Mrs. Grayling slipped into a small stand of head-high bushes in the side yard. From her hiding place, she could see the front and one side of the house.

The first floor was dark, but several of the upper windows were lit.

A squat shadow passed behind the largest one. Mrs. Bellingsworth’s bedroom, perhaps. Mrs. Bellingsworth used a wheelchair, of course. Undoubtedly the chairlift enabled her to get to the second floor. Perhaps she had another wheelchair waiting for her at the head of the stairs.

Miss Grayling thought how satisfying it would be to shove the wheelchair, Mrs. Bellingsworth and all, down that elegant curved staircase. She might break her neck.

But that wasn’t practical. Such a fall might be fatal, but then again, it might not. And if it were not, Mrs. Bellingsworth would be able to tell the authorities exactly who had pushed her. Much as Miss Grayling would like to confront the woman directly, the identity of the perpetrator of any attempt to silence the dreadful Mrs. Bellingsworth had to remain unknown.

That, Miss Grayling realized, should not be a problem. Blackmailers had to be good at keeping their secrets. So the only connection between them would be the invitation to tea. She smiled into the dark. Such an ordinary activity for ladies of a certain age!

Miss Grayling hurried across the lawn and hid next to the house in the shadow of a large bush. A soft clicking startled her. She looked around frantically.

A meter. It had four small numbered dials. As she watched, the one on the right spun and the meter clicked again.

Miss Grayling’s house had a meter like this. Not for water. Nor electricity. It metered gas.

She remembered the fireplace in Mrs. Bellingsworth’s parlor, with the cheerful gas fire burning on artificial logs.

Perhaps Mrs. Bellingsworth’s kitchen range used gas. Or her clothes dryer. Or water heater. She might even heat her house with gas.

A broken gas line could be very dangerous, Miss Grayling knew. An accumulation of gas vapors could explode and set the house on fire, this house with a wooden frame, covered with wooden siding.

Such a pity that Mrs. Bellingsworth had an upstairs bedroom.

And she used a wheelchair.

Would she be able to get out of bed, into the wheelchair, down the stairs on the lift, and into another wheelchair in time to escape a fire? Miss Grayling doubted it.

And Mrs. Bellingsworth lived alone. She’d told Beatrice to “go home.”

The night grew chillier. The rain tapered off, and a harsh wind picked up. Miss Grayling stood quietly, waiting for the rectangles of light cast on the lawn to flick out.

When they did, Miss Grayling crept out of her sheltered spot. The bitter wind sent cold fingers down her neck. She pulled the scarf tighter as she climbed the steps to the back porch.

She took out her set of skeleton keys, selected one that was similar to the lock on her own back door, and by the light of the small flashlight, inserted it into the lock. A little jiggling, a sharp slap on the doorjamb, and the door swung open with a deafening creak.

Miss Grayling shut off her flashlight and stood still, half expecting a light to flash on, a neighbor to raise an alarm, a dog to bark.

Nothing.

She slipped inside Mrs. Bellingsworth’s kitchen, closed the door gently behind her, and turned the flashlight back on.

A sturdy table stood in the middle of the kitchen. The sink was stone. The massive old kitchen range was indeed fueled by gas. She turned on one of the burners. It hissed as the gas fed into the ring.

She turned off the gas and went through the swinging door into the dining room. Beyond that was the parlor where she’d met Mrs. Bellingsworth.

The gas fireplace stood cold and dark along an outside wall. Unlike the kitchen appliances, it appeared to be a recent improvement. Shielding the flashlight’s beam with a cupped palm, Miss Grayling examined the fireplace.

A remote control sat on the mantel. Curious, she pushed the button that said “on.”

The whoosh of flames in the fireplace startled her, and she pushed the “off” button.

The flames died down.

How stupid of her to push buttons when she had no idea what might happen! Suppose it had been a remote for the TV and sound had come blasting out?

Miss Grayling stood for several minutes, trying to calm her nerves. She was not thinking clearly.

But she couldn’t let this opportunity pass.

She turned the fireplace back on. Flickering flames cast dancing shadows on the walls.

Was the mantel within Mrs. Bellingsworth’s reach when she sat in her wheelchair? Miss Grayling thought it must be. The fire had been burning when Miss Grayling left, after all, and Beatrice had gone home, so Mrs. Bellingsworth must have been able to turn it off.

Leaving the fire burning, Miss Grayling put the remote back where she’d found it. Carefully leaving the pocket door open between the parlor and the dining room, she passed through the swinging door and into the kitchen.

Back at the stove, she turned on the burner, waited to hear the hiss of gas, then blowing hard, extinguished the flame.

Then she slipped out the back door and hurried away.

Would the flames from the fireplace ignite the gas in the kitchen? Miss Grayling had no way of knowing for sure. She’d have to leave that to Providence.

Some things were out of one’s control.

Miss Grayling had reached her back porch when a sudden roar tore through the night.

Bright flames lit up the sky.

Smiling, she opened the door and hurried inside.

She would make herself a cup of tea, perhaps with a bit of whiskey in it to calm her nerves.

As she hung her raincoat on a hook just inside the door, the sound of screaming sirens filled the night.

Yes, definitely a good bit of whiskey in that tea.

* * * *

Mrs. Bellingsworth’s memorial service was held at the Jesus Is Our Savior church.

The man in charge of the ceremony—he had not introduced himself, so Miss Grayling did not know whether he was a minister, a funeral director, or perhaps a local handyman who happened to own a suit and had been pressed into service—gave a short, generic presentation that was undoubtedly intended, as the parlance was these days, “to celebrate the life” of Mrs. Bellingsworth.

Miss Grayling saw very little to celebrate, but she was grateful that the ceremony was brief.

The attendees, few in number, were ushered down the stairs into a basement room and seated at tables covered with white cloths, decorated with small flower arrangements in the center. A buffet table of sandwiches and cakes stood against the back wall.

The offerings were not sumptuous, but if they had been prepared by the ample ladies in aprons who waited by the kitchen door, they would be filling and tasty.

Miss Grayling held back so that she was not the first person in line. She selected a variety of sandwiches and accepted a glass of lemonade, then headed for a table in the corner.

No sooner had she taken a bite of a well-seasoned seafood-salad sandwich when someone said, “Miss Grayling, isn’t it?”

Beatrice, the maid, stood uncertainly next to her with an overfilled plate in her hand.

Beatrice was not in proper mourning garb, but she wore a gray sweater with a black skirt and a black blouse. A nod toward appropriate dress, at least.

“Please sit down,” Miss Grayling said, afraid that the contents of the woman’s plate would spill at any moment. Probably onto Miss Grayling’s own proper black dress.

“Thank you.” Beatrice sat down stiffly.

“I’m sorry for your loss.” Miss Grayling struggled to think of anything meaningful to say. “I hope you will not have too much difficulty finding another similar position.”

Beatrice let out a low laugh. “Another similar position? I don’t think so! I have a job at the nursing home all lined up. It pays better and has benefits and everything.”

Miss Grayling took a sip of her lemonade. This situation called for nothing but vapid, if polite, conversation. “Indeed?”

“I earned my nursing assistant certification almost a year ago, but Mrs. Bellingsworth wouldn’t let me leave.”

Miss Grayling looked up from her triangle of pimento cheese. “How could she not let you leave? Just give two weeks’ notice and go.”

Much to Miss Grayling’s surprise, a tear formed in the corner of Beatrice’s eye. “Mrs. Bellingsworth knew… ” She choked on the words. “If I left, she threatened to tell everyone all about… ” Beatrice’s voice trailed off. “I’d rather not talk about it.”

“Of course, my dear.” Miss Grayling patted her hand gently. “Perhaps it would be best if your secret died with Mrs. Bellingsworth.”

Beatrice looked up, her eyes shiny. “You think so? Some people say you should face such things, bring them out in the open. Man up, so to speak.”

“An odd idea, that a young woman should ‘man up,’” Miss Grayling mused aloud. “As long as there have been human societies, there have been people whose secrets have gone to the grave with them. Why should things be any different today?”

“You really think so?” Beatrice sniffed and reached for a napkin.

Miss Grayling opened her purse and handed the maid an embroidered handkerchief. “I do.”

Beatrice snorted, a most unladylike sound, and instead of dabbing delicately at her eyes, rubbed them hard.

While Miss Grayling would regret the loss of one of her fine linen handkerchiefs, she hoped Beatrice would not feel obliged to return it unless she took it home and laundered it first.

“Was Mrs. Bellingsworth threatening to tell a secret about you?” Beatrice put the handkerchief to her nose and gave a tremendous honk.

Miss Grayling decided she didn’t want the handkerchief back, even laundered. “What would make you think that?” she asked cautiously.

“That’s what Mrs. Bellingsworth did, you know. She invited ladies over for brunch or tea and threatened to tell their secrets if they didn’t pay up.”

“Really?” Miss Grayling tried to think of a way to steer the conversation away from such a dangerous subject.

“Yes, really.”

Another lady she knew from church, Mrs. Hotchkiss, wandered over bearing a glass of lemonade and a plate of tiny cakes. “May I join you?”

“By all means.” Miss Grayling said, welcoming the interruption.

Beatrice waited until the woman was seated before speaking up. “Mrs. Bellingsworth recently had you over for brunch,” she said. “We were wondering if she had discovered some secret in your life, as she had in ours?”

Although Miss Grayling objected to being included in Beatrice’s “we,” she said nothing, hoping that Mrs. Hotchkiss would answer.

Mrs. Hotchkiss emitted a harsh barking laugh. “Funny you should ask that.” She shoveled a small cake whole into her mouth, chewed several times, and swallowed. “My front lawn is torn up with that despicable sewer project. And would you believe that Mrs. Bellingsworth claimed that something incriminating had been uncovered? I can’t imagine what she was thinking of.”

Miss Grayling’s heart fluttered. “How extraordinary,” she said, hoping to encourage a more complete answer.

Mrs. Hotchkiss snorted. “Indeed. I told her to go right ahead and call the police. And the newspapers, too. I have nothing to hide.”

Beatrice’s eyes opened wide. “You have no secrets?”

“None worth paying to keep quiet about. When I was younger, I thought it was important to conceal how abusive Jonathan, my late husband, had been toward me and the children. When Jonathan left us, there was a rumor that my son had killed his father and buried him in the yard.” She laughed. “What a lot of bologna! Jonathan sent me monthly support checks, which he surely couldn’t have done from six feet under! And when he finally died, I received a generous insurance settlement.” She selected another cake. “I believe Mrs. Bellingsworth was trying to play on the old rumors. I told her flat out there was no truth in them, and that she was most welcome to come dig in my yard herself if she thought there were any bodies to be found.”

“She invited people over as their yards were dug up,” Beatrice said. “She only hinted at what had been found. Some people would be worried enough to pay her off.”

Miss Grayling leaned back in her chair. How many people had Mrs. Bellingsworth blackmailed over the years, leaving people to scrape together outrageous sums of money they could ill afford? She had no remorse for the role she played in dispatching Mrs. Bellingsworth. The despicable woman was dead. Her power over people had died with her. Blackmailers flirted with death every day. Someone was bound to put an end to it eventually.

She glanced at Beatrice, who was drying her tears. As she surveyed the room, not one person in the gathering looked the least bit mournful. Several of the ladies were positively jovial, talking animatedly with smiles on their faces.

Perhaps Miss Grayling had done more good than she ever could have imagined.

But her part must, of course, remain a secret, a secret to the grave.

KM Rockwood draws on a varied background for her stories, including working as a laborer in a steel fabrication factory and supervising an inmate work crew in a large state prison. Since she retired from working as a special-education teacher in correctional facilities, inner-city schools and alternative schools, she has devoted her time to writing and caring for her family and pets. Her published works include the Jesse Damon Crime Novel series (Wildside Press) and numerous short stories. www.kmrockwood.com