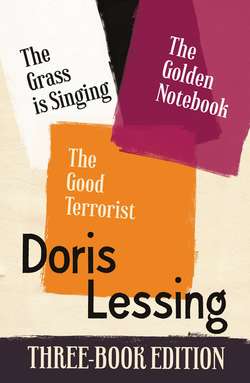

Читать книгу Doris Lessing Three-Book Edition: The Golden Notebook, The Grass is Singing, The Good Terrorist - Doris Lessing - Страница 25

Free Women 1

ОглавлениеAnna meets her friend Molly in the summer of 1957 after a separation…

The two women were alone in the London flat.

‘The point is,’ said Anna, as her friend came back from the telephone on the landing, ‘the point is, that as far as I can see, everything’s cracking up.’

Molly was a woman much on the telephone. When it rang she had just enquired: ‘Well, what’s the gossip?’ Now she said, ‘That’s Richard, and he’s coming over. It seems today’s his only free moment for the next month. Or so he insists.’

‘Well I’m not leaving,’ said Anna.

‘No, you stay just where you are.’

Molly considered her own appearance—she was wearing trousers and a sweater, both the worse for wear. ‘He’ll have to take me as I come,’ she concluded, and sat down by the window. ‘He wouldn’t say what it’s about—another crisis with Marion, I suppose.’

‘Didn’t he write to you?’ asked Anna, cautious.

‘Both he and Marion wrote—ever such bonhomous letters. Odd, isn’t it?’

This odd, isn’t it? was the characteristic note of the intimate conversations they designated gossip. But having struck the note, Molly swerved off with: ‘It’s no use talking now, because he’s coming right over, he says.’

‘He’ll probably go when he sees me here,’ said Anna, cheerfully, but slightly aggressive. Molly glanced at her, keenly, and said: ‘Oh, but why?’

It had always been understood that Anna and Richard disliked each other; and before, Anna had always left when Richard was expected. Now Molly said: ‘Actually I think he rather likes you, in his heart of hearts. The point is, he’s committed to liking me, on principle—he’s such a fool he’s always got to either like or dislike someone, so all the dislike he won’t admit he has for me gets pushed off on to you.’

It’s a pleasure,’ said Anna. ‘But do you know something? I discovered while you were away that for a lot of people you and I are practically interchangeable.’

‘You’ve only just understood that?’ said Molly, triumphant as always when Anna came up with—as far as she was concerned—facts that were self-evident.

In this relationship a balance had been struck early on: Molly was altogether more worldly-wise than Anna who, for her part, had a superiority of talent.

Anna held her own private views. Now she smiled, admitting that she had been very slow.

‘When we’re so different in every way,’ said Molly, ‘it’s odd. I suppose because we both live the same kind of life—not getting married and so on. That’s all they see.’

Free women,’ said Anna, wryly. She added, with an anger new to Molly, so that she earned another quick scrutinizing glance from her friend: ‘They still define us in terms of relationships with men, even the best of them.’

‘Well, we do, don’t we?’ said Molly, rather tart. ‘Well, it’s awfully hard not to,’ she amended, hastily, because of the look of surprise Anna now gave her. There was a short pause, during which the women did not look at each other but reflected that a year apart was a long time, even for an old friendship.

Molly said at last, sighing: ‘Free. Do you know, when I was away, I was thinking about us, and I’ve decided that we’re a completely new type of woman. We must be, surely?’

‘There’s nothing new under the sun,’ said Anna, in an attempt at a German accent. Molly, irritated—she spoke half a dozen languages well—said: ‘There’s nothing new under the sun,’ in a perfect reproduction of a shrewd old woman’s voice, German accented.

Anna grimaced, acknowledging failure. She could not learn languages, and was too self-conscious ever to become somebody else: for a moment Molly had even looked like Mother Sugar, otherwise Mrs Marks, to whom both had gone for psycho-analysis. The reservations both had felt about the solemn and painful ritual were expressed by the pet name, ‘Mother Sugar’; which, as time passed, became a name for much more than a person, and indicated a whole way of looking at life—traditional, rooted, conservative, in spite of its scandalous familiarity with everything amoral. In spite of—that was how Anna and Molly, discussing the ritual, had felt it; recently Anna had been feeling more and more it was because of; and this was one of the things she was looking forward to discussing with her friend.

But now Molly, reacting as she had often done in the past, to the slightest suggestion of a criticism from Anna of Mother Sugar, said quickly: ‘All the same, she was wonderful and I was in much too bad a shape to criticize.’

‘Mother Sugar used to say, “You’re Electra”, or ‘You’re Antigone”, and that was the end, as far as she was concerned,’ said Anna.

‘Well, not quite the end,’ said Molly, wryly insisting on the painful probing hours both had spent.

‘Yes,’ said Anna, unexpectedly insisting, so that Molly, for the third time, looked at her curiously. ‘Yes. Oh I’m not saying she didn’t do me all the good in the world. I’m sure I’d never have coped with what I’ve had to cope with without her. But all the same…I remember quite clearly one afternoon, sitting there—the big room, and the discreet wall lights, and the Buddha and the pictures and the statues.’

‘Well?’ said Molly, now very critical.

Anna, in the face of this unspoken but clear determination not to discuss it, said: ‘I’ve been thinking about it all during the last few months…no, I’d like to talk about it with you. After all, we both went through it, and with the same person…’

‘Well?’

Anna persisted: ‘I remember that afternoon, knowing I’d never go back. It was all that damned art all over the place.’

Molly drew in her breath, sharp. She said, quickly: ‘I don’t know what you mean.’ As Anna did not reply, she said, accusing: ‘And have you written anything since I’ve been away?’

‘No.’

‘I keep telling you,’ said Molly, her voice shrill, ‘I’ll never forgive you if you throw that talent away. I mean it. I’ve done it, and I can’t stand watching you—I’ve messed with painting and dancing and acting and scribbling, and now…you’re so talented, Anna. Why? I simply don’t understand.’

‘How can I ever say why, when you’re always so bitter and accusing?’

Molly even had tears in her eyes, which were fastened in the most painful reproach on her friend. She brought out with difficulty: ‘At the back of my mind I always thought, well, I’ll get married, so it doesn’t matter my wasting all the talents I was born with. Until recently I was even dreaming about having more children—yes I know it’s idiotic but it’s true. And now I’m forty and Tommy’s grown up. But the point is, if you’re not writing simply because you’re thinking about getting married…’

‘But we both want to get married,’ said Anna, making it humorous; the tone restored reserve to the conversation; she had understood, with pain, that she was not, after all, going to be able to discuss certain subjects with Molly.

Molly smiled, drily, gave her friend an acute, bitter look, and said: ‘All right, but you’ll be sorry later.’

‘Sorry,’ said Anna, laughing, out of surprise. ‘Molly, why is it you’ll never believe other people have the disabilities you have?’

‘You were lucky enough to be given one talent, and not four.’

‘Perhaps my one talent has had as much pressure on it as your four?’

‘I can’t talk to you in this mood. Shall I make you some tea while we’re waiting for Richard?’

‘I’d rather have beer or something.’ She added, provocative: ‘I’ve been thinking I might very well take to drink later on.’

Molly said, in the older sister’s tone Anna had invited: ‘You shouldn’t make jokes, Anna. Not when you see what it does to people—look at Marion. I wonder if she’s been drinking while I was away?’

‘I can tell you. She has—yes, she came to see me several times.’

‘She came to see you?’

‘That’s what I was leading up to, when I said you and I seem to be interchangeable.’

Molly tended to be possessive—she showed resentment, as Anna had known she would, as she said: ‘I suppose you’re going to say Richard came to see you too?’ Anna nodded; and Molly said, briskly, ‘I’ll get us some beer.’ She returned from the kitchen with two long cold-beaded glasses, and said: ‘Well you’d better tell me all about it before Richard comes, hadn’t you?’

Richard was Molly’s husband; or rather, he had been her husband. Molly was the product of what she referred to as ‘one of those ’twenties marriages’. Her mother and father had both glittered, but briefly, in the intellectual and bohemian circles that had spun around the great central lights of Huxley, Lawrence, Joyce, etc. Her childhood had been disastrous, since this marriage only lasted a few months. She had married, at the age of eighteen, the son of a friend of her father’s. She knew now she had married out of a need for security and even respectability. The boy Tommy was a product of this marriage. Richard at twenty had already been on the way to becoming the very solid businessman he had since proved himself: and Molly and he had stood their incompatibility for not much more than a year. He had then married Marion, and there were three boys. Tommy had remained with Molly. Richard and she, once the business of the divorce was over, became friends again. Later, Marion became her friend. This, then, was the situation to which Molly often referred as: ‘It’s all very odd, isn’t it?’

‘Richard came to see me about Tommy,’ said Anna.

‘What? Why?’

‘Oh—idiotic! He asked me if I thought it was good for Tommy to spend so much time brooding. I said I thought it was good for everyone to brood, if by that he meant, thinking; and that since Tommy was twenty and grown up it was not for us to interfere anyway.’

‘Well it isn’t good for him,’ said Molly.

‘He asked me if I thought it would be good for Tommy to go off on some trip or other to Germany—a business trip, with him. I told him to ask Tommy, not me. Of course Tommy said no.’

‘Of course. Well I’m sorry Tommy didn’t go.’

‘But the real reason he came, I think, was because of Marion. But Marion had just been to see me, and had a prior claim, so to speak. So I wouldn’t discuss Marion at all. I think it’s likely he’s coming to discuss Marion with you.’

Molly was watching Anna closely. ‘How many times did Richard come?’

‘About five or six times.’

After a silence, Molly let her anger spurt out with: ‘It’s very odd he seems to expect me almost to control Marion. Why me? Or you? Well, perhaps you’d better go after all. It’s going to be difficult if all sorts of complications have been going on while my back was turned.’

Anna said firmly: ‘No, Molly. I didn’t ask Richard to come and see me. I didn’t ask Marion to come and see me. After all, it’s not your fault or mine that we seem to play the same role for people. I said what you would have said—at least, I think so.’

There was a note of humorous, even childish pleading in this. But it was deliberate. Molly, the older sister, smiled and said: ‘Well, all right.’ She continued to observe Anna narrowly; and Anna was careful to appear unaware of it. She did not want to tell Molly what had happened between her and Richard now; not until she could tell her the whole story of the last miserable year.

‘Is Marion drinking badly?’

‘Yes, I think she is.’

‘And she told you all about it?’

‘Yes. In detail. And what’s odd is, I swear she talked as if I were you—even making slips of the tongue, calling me Molly and so on.’

‘Well, I don’t know,’ said Molly. ‘Who would ever have thought? And you and I are different as chalk and cheese.’

‘Perhaps not so different,’ said Anna, drily; but Molly laughed in disbelief.

She was a tallish woman, and big-boned, but she appeared slight, and even boyish. This was because of how she did her hair, which was a rough, streaky gold, cut like a boy’s; and because of her clothes, for which she had a great natural talent. She took pleasure in the various guises she could use: for instance, being a hoyden in lean trousers and sweaters, and then a siren, her large green eyes made-up, her cheekbones prominent, wearing a dress which made the most of her full breasts.

This was one of the private games she played with life, which Anna envied her; yet in moments of self-rebuke she would tell Anna she was ashamed of herself, she so much enjoyed the different roles: ‘It’s as if I were really different—don’t you see? I even feel a different person. And there’s something spiteful in it—that man, you know, I told you about him last week—he saw me the first time in my old slacks and my sloppy old jersey, and then I rolled into the restaurant, nothing less than a femme fatale, and he didn’t know how to have me, he couldn’t say a word all evening, and I enjoyed it. Well, Anna?’

‘But you do enjoy it,’ Anna would say, laughing.

But Anna was small, thin, dark, brittle, with large black always-on-guard eyes, and a fluffy haircut. She was, on the whole, satisfied with herself, but she was always the same. She envied Molly’s capacity to project her own changes of mood. Anna wore neat, delicate clothes, which tended to be either prim, or perhaps a little odd; and relied upon her delicate white hands, and her small, pointed white face to make an impression. But she was shy, unable to assert herself, and, she was convinced, easily overlooked.

When the two women went out together, Anna deliberately effaced herself and played to the dramatic Molly. When they were alone, she tended to take the lead. But this had by no means been true at the beginning of their friendship. Molly, abrupt, straightforward, tactless, had frankly domineered Anna. Slowly, and the offices of Mother Sugar had had a good deal to do with it, Anna learned to stand up for herself. Even now there were moments when she should challenge Molly when she did not. She admitted to herself she was a coward; she would always give in rather than have fights or scenes. A quanrel would lay Anna low for days, whereas Molly thrived on them. She would burst into exuberant tears, say unforgivable things, and have forgotten all about it half a day later. Meanwhile Anna would be limply recovering in her flat.

That they were both ‘insecure’ and ‘unrooted’, words which dated from the era of Mother Sugar, they both freely acknowledged. But Anna had recently been learning to use these words in a different way, not as something to be apologized for, but as flags or banners for an attitude that amounted to a different philosophy. She had enjoyed fantasies of saying to Molly: We’ve had the wrong attitude to the whole thing, and it’s Mother Sugar’s fault—what is this security and balance that’s supposed to be so good? What’s wrong with living emotionally from hand-to-mouth in a world that’s changing as fast as it is?

But now, sitting with Molly talking, as they had so many hundreds of times before, Anna was saying to herself: Why do I always have this awful need to make other people see things as I do? It’s childish, why should they? What it amounts to is that I’m scared of being alone in what I feel.

The room they sat in was on the first floor, overlooking a narrow side street, whose windows had flower boxes and painted shutters, and whose pavements were decorated with three basking cats, a pekinese and the milk-cart, late because it was Sunday. The milkman had white shirt-sleeves, rolled up; and his son, a boy of sixteen, was sliding the gleaming white bottles from a wire basket on to the doorsteps. When he reached under their window, the man looked up and nodded. Molly said: ‘Yesterday he came in for coffee. Full of triumph, he was. His son’s got a scholarship and Mr Gates wanted me to know it. I said to him, getting in before he could, “My son’s had all these advantages, and all that education, and look at him, he doesn’t know what to do with himself. And yours hasn’t had a penny spent on him and he’s got a scholarship.” “That’s right,” he said, “that’s the way of it.” Then I thought, well I’m damned if I’ll sit here, taking it, so I said: “Mr Gates, your son’s up into the middle-class now, with us lot, and you won’t be speaking the same language. You know that, don’t you?” “It’s the way of the world,” he says. I said, “It’s not the way of the world at all, it’s the way of this damned class-ridden country.” He’s one of those bloody working-class Tories, Mr Gates is, and he said: “It’s the way of the world, Miss Jacobs, you say your son doesn’t see his way forward? That’s a sad thing.” And off he went on his milk-round, and I went upstairs and there was Tommy sitting on his bed, just sitting. He’s probably sitting there now, if he’s in. The Gates boy, he’s all of a piece, he’s going out for what he wants. But Tommy—since I came back three days ago, that’s all he’s done, sat on his bed and thought.’

‘Oh, Molly, don’t worry so much. He’ll turn out all right.’ They were leaning over the sill, watching Mr Gates and his son. A short, brisk, tough little man; and his son was tall, tough and good-looking. The women watched how the boy, returning with an empty basket, swung out a filled one from the back of the milk-cart, receiving instructions from his father with a smile and a nod. There was perfect understanding there; and the two women, both of them bringing up children without men, exchanged a grimacing envious smile.

‘The point is,’ said Anna, ‘neither of us was prepared to get married simply to give our children fathers. So now we must take the consequences. If there are any. Why should there be?’

‘It’s very well for you,’ said Molly, sour; ‘you never worry about anything, you just let things slide.’

Anna braced herself—almost did not reply, and then with an effort said: ‘I don’t agree, we try to have things both ways. We’ve always refused to live by the book and the rule; but then why start worrying because the world doesn’t treat us by rule? That’s what it amounts to.’

‘There you are,’ said Molly, antagonistic; ‘but I’m not a theoretical type. You always do that—faced with something, you start making up theories. I’m simply worried about Tommy.’

Now Anna could not reply: her friend’s tone was too strong. She returned to her survey of the street. Mr Gates and his boy were turning the corner out of sight, pulling the red milk-cart behind them. At the opposite end of the street was a new interest: a man pushing a hand-cart. ‘Fresh country strawberries,’ he was shouting. ‘Picked fresh this morning, morning-picked country strawberries…’

Molly glanced at Anna, who nodded, grinning like a small girl. (She was disagreeably conscious that the little-girl smile was designed to soften Molly’s criticism of her.) ‘I’ll get some for Richard too,’ said Molly, and ran out of the room, picking up her handbag from a chair.

Anna continued to lean over the sill, in a warm space of sunlight, watching Molly, who was already in energetic conversation with the strawberry seller. Molly was laughing and gesticulating, and the man shook his head and disagreed, while he poured the heavy red fruit on to his scales.

‘Well you’ve no overhead costs,’ Anna heard, ‘so why should we pay just what we would in the shops?’

‘They don’t sell morning-fresh strawberries in the shops, miss, not like these.’

‘Oh go on,’ said Molly, as she disappeared with her white bowl of red fruit. ‘Sharks, that’s what you are!’

The strawberry man, young, yellow, lean and deprived, lifted a snarling face to the window where Molly had already inserted herself. Seeing the two women together he said, as he fumbled with his glittering scales, ‘Overhead costs, what do you know about it?’

‘Then come up and have some coffee and tell us,’ said Molly, her face vivid with challenge.

At which he lowered his face and said to the street floor: ‘Some people have to work, if others haven’t.’

‘Oh go on,’ said Molly, ‘don’t be such a sourpuss. Come up and eat some of your strawberries. On me.’

He didn’t know how to take her. He stood, frowning, his young face uncertain under an over-long slope of greasy fairish hair. ‘I’m not that sort, if you are,’ he remarked, at last, offstage, as it were.

‘So much the worse for you,’ said Molly, leaving the window, laughing at Anna in a way which refused to be guilty.

But Anna leaned out, confirmed her view of what had happened by a look at the man’s dogged, resentful shoulders, and said in a low voice: ‘You hurt his feelings.’

‘Oh hell,’ said Molly, shrugging. ‘It’s coming back to England again—everybody so shut up, taking offence, I feel like breaking out and shouting and screaming whenever I set foot on this frozen soil. I feel locked up, the moment I breathe our sacred air.’

‘All the same,’ said Anna, ‘he thinks you were laughing at him.’

Another customer had slopped out of the opposite house; a woman in Sunday comfort, slacks, loose shirt and a yellow scarf around her head. The strawberry man served her, non-committal. Before he lifted the handles to propel the cart onwards, he looked up again at the window, and seeing only Anna, her small sharp chin buried in her forearm, her black eyes fixed on him, smiling, he said with grudging good-humour: ‘Overhead costs, she says…’ and snorted lightly with disgust. He had forgiven them.

He moved off up the street behind the mounds of softly-red, sunglistening fruit, shouting: ‘Morning-fresh strawberries. Picked this morning!’ Then his voice was absorbed into the din of traffic from the big street a couple of hundred yards down.

Anna turned and found Molly setting bowls of the fruit, loaded with cream, on the sill. ‘I’ve decided not to waste any on Richard,’ said Molly, ‘he never enjoys anything anyway. More beer?’

‘With strawberries, wine, obviously,’ said Anna greedily; and moved the spoon about among the fruit, feeling its soft sliding resistance, and the slipperiness of the cream under a gritty crust of sugar. Molly swiftly filled glasses with wine and set them on the white sill. The sunlight crystallized beside each glass on the white paint in quivering lozenges of crimson and yellow light, and the two women sat in the sunlight, sighing with pleasure and stretching their legs in the thin warmth, looking at the colours of the fruit in the bright bowls and at the red wine.

But now the door-bell rang, and both instinctively gathered themselves into more tidy postures. Molly leaned out of the window again, shouted: ‘Mind your head!’ and threw down the door-key, wrapped in an old scarf.

They watched Richard lean down to pick up the key, without even a glance upwards, though he must know that at least Molly was there. ‘He hates me doing that, ’she said, isn’t it odd? After all these years? And his way of showing it is simply to pretend it didn’t happen.’

Richard came into the room. He looked younger than his middle age, being well-tanned after an early summer holiday in Italy. He wore a tight yellow sports shirt, and new light trousers: every Sunday of his year, summer or winter, Richard Portmain wore clothes that claimed him for the open air. He was a member of various suitable golf and tennis clubs, but never played unless for business reasons. He had had a cottage in the country for years; but sent his family to it alone, unless it was advisable to entertain business friends for a week-end. He was by every instinct urban. He spent his week-ends dropping from one club, one pub, one bar, to the next. He was a shortish, dark, compact man, almost fleshy. His round face, attractive when he smiled, was obstinate to the point of sullenness when he was not smiling. His whole solid person—head poked out forward, eyes unblinking, had this look of dogged determination. He now impatiently handed Molly the key, that was loosely bundled inside her scarlet scarf. She took it and began trickling the soft material through her solid white fingers, remarking: ‘Just off for a healthy day in the country, Richard?’

Having braced himself for just such a jibe, he now stiffly smiled, and peered into the dazzle of sunlight around the white window. When he distinguished Anna, he involuntarily frowned, nodded stiffly, and sat down hastily across the room from both of them, saying: ‘I didn’t know you had a visitor, Molly.’

‘Anna isn’t a visitor,’ said Molly.

She deliberately waited until Richard had had the full benefit of the sight of them, indolently displayed in the sunshine, heads turned towards him in benevolent enquiry, and offered: ‘Wine, Richard? Beer? Coffee? Or a nice cup of tea perhaps?’

‘If you’ve got a Scotch, I wouldn’t mind.’

‘Beside you,’ said Molly.

But having made what he clearly felt to be a masculine point, he didn’t move. ‘I came to discuss Tommy.’ He glanced at Anna, who was licking up the last of her strawberries.

‘But you’ve already discussed all this with Anna, so I hear, so now we can all three discuss it.’

‘So Anna’s told you…’

‘Nothing,’ said Molly. ‘This is the first time we’ve had a chance to see each other.’

‘So I’m interrupting your first heart to heart,’ said Richard, with a genuine effort towards jovial tolerance. He sounded pompous, however, and both women looked amusedly uncomfortable, in response to it.

Richard abruptly got up.

‘Going already?’ enquired Molly.

‘I’m going to call Tommy.’ He had already filled his lungs to let out the peremptory yell they both expected, when Molly interrupted with: ‘Richard, don’t shout at him. He’s not a little boy any longer. Besides I don’t think he’s in.’

‘Of course he’s in.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Because he’s looking out of the window upstairs. I’m surprised you don’t even know whether your son is in or not.’

‘Why? I don’t keep a tab on him.’

‘That’s all very well, but where has that got you?’

The two now faced each other, serious with open hostility. Replying to his: Where has that got you? Molly said: ‘I’m not going to argue about how he should have been brought up. Let’s wait until your three have grown up before we score points.’

‘I haven’t come to discuss my three.’

‘Why not? We’ve discussed them hundreds of times. And I suppose you have with Anna too.’

There was now a pause while both controlled their anger, surprised and alarmed it was already so strong. The history of these two was as follows: They had met in 1935. Molly was deeply involved with the cause of Republican Spain. Richard was also. (But, as Molly would remark, on those occasions when he spoke of this as a regrettable lapse into political exoticism on his part: Who wasn’t in those days?) The Portmains, a rich family, precipitously assuming this to be a proof of permanent communist leanings, had cut off his allowance. (As Molly put it: My dear, cut him off without a penny! Naturally Richard was delighted. They had never taken him seriously before. He instantly took out a Party card on the strength of it.) Richard who had a talent for nothing but making money, as yet undiscovered, was kept by Molly for two years, while he prepared himself to be a writer. (Molly; but of course only years later: Can you imagine anything more banal? But of course Richard has to be commonplace in everything. Everyone was going to be a great writer, but everyone! Do you know the really deadly skeleton in the communist closet—the really awful truth? It’s that every one of the old Party war horses—you know, people you’d imagine had never had a thought of anything but the Party for years, everyone has that old manuscript or wad of poems tucked away. Everyone was going to be the Gorki or the Mayakovski of our time. Isn’t it terrifying? Isn’t it pathetic? Every one of them, failed artists. I’m sure it’s significant of something, if only one knew what.) Molly was still keeping Richard for months after she left him, out of a kind of contempt. His revulsion against left-wing politics, which was sudden, coincided with his decision that Molly was immoral, sloppy and bohemian. Luckily for her, however, he had already contracted a liaison with some girl which, though short, was public enough to prevent him from divorcing her and gaining custody of Tommy, which he was threatening to do. He was then readmitted into the bosom of the Portmain family, and accepted what Molly referred to, with amiable contempt, as ‘a job in the City’. She had no idea, even now, just how powerful a man Richard had become by that act of deciding to inherit a position. Richard then married Marion, a very young, warm, pleasant, quiet girl, daughter of a moderately distinguished family. They had three sons.

Meanwhile Molly, talented in so many directions, danced a little but she really did not have the build for a ballerina; did a song and dance act in a revue—decided it was too frivolous; took drawing lessons, gave them up when the war started when she worked as a journalist; gave up journalism to work in one of the cultural outworks of the Communist Party; left for the same reason everyone of her type did—she could not stand the deadly boredom of it; became a minor actress, and had reconciled herself, after much unhappiness, to the fact that she was essentially a dilettante. Her source of self-respect was that she had not—as she put it—given up and crawled into safety somewhere. Into a safe marriage.

And her secret source of uneasiness was Tommy, over whom she had fought a years-long battle with Richard. He was particularly disapproving because she had gone away for a year, leaving the boy in her house, to care for himself.

He now said, resentful: ‘I’ve seen a good deal of Tommy during the last year, when you left him alone…’

She interrupted with: ‘I keep explaining, or trying to—I thought it all out and decided it would be good for him to be left. Why do you always talk as if he were a child? He was over nineteen, and I left him in a comfortable house, with money, and everything organized.’

‘Why don’t you admit you had a whale of a good time junketing all over Europe, without Tommy to tie you?’

‘Of course I had a good time, why shouldn’t I?’

Richard laughed, loudly and unpleasantly, and Molly said, impatient, ‘Oh for God’s sake, of course I was glad to be free for the first time since I had a baby. Why not? And what about you—you have Marion, the good little woman, tied hand and foot to the boys while you do as you like—and there’s another thing. I keep trying to explain and you never listen. I don’t want him to grow up one of these damned mother-ridden Englishmen. I wanted him to break free of me. Yes, don’t laugh, but it wasn’t good, the two of us together in this house, always so close and knowing everything the other one did.’

Richard grimaced with annoyance and said, ‘Yes, I know your little theories on this point.’

At which Anna came in with: ‘It’s not only Molly—all the women I know—I mean, the real women, worry that their sons are going to grow up like…they’ve got good reason to worry.’

At this Richard turned hostile eyes on Anna; and Molly watched the two of them sharply.

‘Like what, Anna?’

‘I would say,’ said Anna, deliberately sweet, ‘just a trifle unhappy about their sex lives? Or would you say that’s putting it too strongly, hmmmm?’

Richard flushed, a dark ugly flush, and turned back to Molly, saying to her: ‘All right, I’m not saying you deliberately did something you shouldn’t.’

‘Thank you.’

‘But what the hell’s wrong with the boy? He never passed an exam decently, he wouldn’t go to Oxford, and now he sits around, brooding and…’

Both Anna and Molly laughed out, at the word brooding.

‘The boy worries me,’ said Richard. ‘He really does.’

‘He worries me,’ said Molly reasonably. ‘And that’s what we’re going to discuss, isn’t it?’

‘I keep offering him things. I invite him to all kinds of things where he’d meet people who’d do him good.’

Molly laughed again.

‘All right, laugh and sneer. But things being as they are, we can’t afford to laugh.’

‘When you said, do him good, I imagined good emotionally. I always forget you’re such a pompous little snob.’

‘Words don’t hurt anyone,’ said Richard, with unexpected dignity. ‘Call me names if you like. You’ve lived one way, I’ve lived another. All I’m saying is, I’m in a position to offer that boy—well, anything he likes. And he’s simply not interested. If he were doing anything constructive with your lot, it’d be different.’

‘You always talk as if I try to put Tommy against you.’

‘Of course you do.’

‘If you mean, that I’ve always said what I thought about the way you live, your values, your success game, that sort of thing, of course I have. Why should I be expected to shut up about everything I believe in? But I’ve always said, there’s your father, you must get to know that world, it exists, after all.’

‘Big of you.’

‘Molly’s always urging him to see more of you,’ said Anna. ‘I know she has. And so have I.’

Richard nodded impatiently, suggesting that what they said was unimportant.

‘You’re so stupid about children, Richard. They don’t like being split,’ said Molly. ‘Look at the people he knows with me—artists, writers, actors and so on.’

‘And politicians. Don’t forget the comrades.’

‘Well, why not? He’ll grow up knowing something about the world he lives in, which is more than you can say about your three—Eton and Oxford, it’s going to be, for all of them. Tommy knows all kinds. He won’t see the world in terms of the little fishpond of the upper class.’

Anna said: ‘You’re not going to get anywhere if you two go on like this.’ She sounded angry; she tried to right it with a joke: ‘What it amounts to is, you two should never have married, but you did, or at least you shouldn’t have had a child, but you did—’ Her voice sounded angry again, and again she softened it, saying, ‘Do you realize you two have been saying the same things over and over for years? Why don’t you accept that you’ll never agree about anything and be done with it?’

‘How can we be done with it when there’s Tommy to consider?’ said Richard, irritably, very loud.

‘Do you have to shout?’ said Anna. ‘How do you know he hasn’t heard every word? That’s probably what’s wrong with him. He must feel such a bone of contention.’

Molly promptly went to the door, opened it, listened. ‘Nonsense, I can hear him typing upstairs.’ She came back saying, ‘Anna, you make me tired when you get English and tight-lipped.’

‘I hate loud voices.’

‘Well I’m Jewish and I like them.’

Richard again visibly suffered. ‘Yes—and you call yourself Miss Jacobs. Miss. In the interests of your right to independence and your own identity—whatever that might mean. But Tommy has Miss Jacobs for a mother.’

‘It’s not the miss you object to,’ said Molly cheerfully. ‘It’s the Jacobs. Yes it is. You always were anti-semitic.’

‘Oh hell,’ said Richard, impatient.

‘Tell me, how many Jews do you number among your personal friends?’

‘According to you I don’t have personal friends, I only have business friends.’

‘Except your girl-friends of course. I’ve noticed with interest that three of your women since me have been Jewish.’

‘For God’s sake,’ said Anna. ‘I’m going home.’ And she actually got off the window-sill. Molly laughed, got up and pushed her down again. ‘You’ve got to stay. Be chairman, we obviously need one.’

‘Very well,’ said Anna, determined. ‘I will. So stop wrangling. What’s it all about, anyway? The fact is, we all agree, we all give the same advice, don’t we?’

‘Do we?’ said Richard.

‘Yes. Molly thinks you should offer Tommy a job in one of your things.’ Like Molly, Anna spoke with automatic contempt of Richard’s world, and he grinned in irritation.

‘One of my things? And you agree, Molly?’

‘If you’d give me a chance to say so, yes.’

‘There we are,’ said Anna. ‘No grounds even for argument.’

Richard now poured himself a whisky, looking humorously patient; and Molly waited, humorously patient.

‘So it’s all settled?’ said Richard.

‘Obviously not,’ said Anna. ‘Because Tommy has to agree.’

‘So we’re back where we started. Molly, may I know why you aren’t against your precious son being mixed up with the hosts of mammon?’

‘Because I’ve brought him up in such a way that—he’s a good person. He’s all right.’

‘So he can’t be corrupted by me?’ Richard spoke with controlled anger, smiling. ‘And may I ask where you get your extraordinary assurance about your values—they’ve taken quite a knock in the last two years, haven’t they?’

The two women exchanged glances, which said: He was bound to say it, let’s get it over with.

‘It hasn’t occurred to you that the real trouble with Tommy is that he’s been surrounded half his life with communists or so-called communists—most of the people he’s known have been mixed up in one way and another. And now they’re all leaving the Party, or have left—don’t you think it might have had some effect?’

‘Well, obviously,’ said Molly.

‘Obviously,’ said Richard, grinning in irritation. ‘Just like that—but what price your precious values—Tommy’s been brought up on the beauty and freedom of the glorious Soviet fatherland.’

‘I’m not discussing politics with you, Richard.’

‘No,’ said Anna, ‘of course you shouldn’t discuss politics.’

‘Why not, when it’s relevant?’

‘Because you don’t discuss them,’ said Molly. ‘You simply use slogans out of the newspapers.’

‘Well can I put it this way? Two years ago you and Anna were rushing out to meetings and organizing everything in sight…’

‘I wasn’t, anyhow,’ said Anna.

‘Don’t quibble. Molly certainly was. And now what? Russia’s in the doghouse and what price the comrades now? Most of them having nervous breakdowns or making a lot of money, as far as I can make out.’

‘The point is,’ said Anna, ‘that socialism is in the doldrums in this country…’

‘And everywhere else.’

‘All right. If you’re saying that one of Tommy’s troubles is that he was brought up a socialist and it’s not an easy time to be a socialist—well of course we agree.’

‘The royal we. The socialist we. Or just the we of Anna and Molly?’

‘Socialist, for the purposes of this argument,’ said Anna.

‘And yet in the last two years you’ve made an about-turn.’

‘No we haven’t. It’s a question of a way of looking at life.’

‘You want me to believe that the way you look at life, which is a sort of anarchy, as far as I can make out, is socialist?’

Anna glanced at Molly; Molly ever-so-slightly shook her head, but Richard saw it, and said, ‘No discussion in front of the children, is that it? What astounds me is your fantastic arrogance. Where do you get it from, Molly? What are you? At the moment you’ve got a part in a masterpiece called The Wings of Cupid.’

‘We minor actresses don’t choose our plays. Besides, I’ve been bumming around for a year, not earning, and I’m broke.’

‘So your assurance comes from the bumming around? It certainly can’t come from the work you do.’

‘I call a halt,’ said Anna. ‘I’m chairman—this discussion is closed. We’re talking about Tommy.’

Molly ignored Anna, and attacked. ‘What you say about me may or may not be true. But where do you get your arrogance from? I don’t want Tommy to be a businessman. You are hardly an advertisement for the life. Anyone can be a businessman, why, you’ve often said so to me. Oh come off it, Richard, how often have you dropped in to see me and sat there saying how empty and stupid your life is?’

Anna made a quick warning movement, and Molly said, shrugging, ‘All right, I’m not tactful. Why should I be? Richard says my life isn’t up to much, well I agree with him, but what’s his? Your poor Marion, treated like a housewife or a hostess, but never as a human being. Your boys, being put through the upper-class mill simply because you want it, given no choice. Your stupid little affairs. Why am I supposed to be impressed?’

‘I see that you two have after all discussed me,’ said Richard, giving Anna a look of open hostility.

‘No we haven’t,’ said Anna. ‘Or nothing we haven’t said for years. We’re discussing Tommy. He came to see me and I told him he should go and see you, Richard, and see if he couldn’t do one of those expert jobs, not business, it’s stupid to be just business, but something constructive, like the United Nations or Unesco. He could get in through you, couldn’t he?’

‘Yes, he could.’

‘What did he say, Anna?’ asked Molly.

‘He said he wanted to be left alone to think. And why not? He’s twenty. Why shouldn’t he think and experiment with life, if that’s what he wants? Why should we bully him?’

‘The trouble with Tommy is he’s never been bullied,’ said Richard.

‘Thank you,’ said Molly.

‘He’s never had any direction. Molly’s simply left him alone as if he was an adult, always. What sort of sense do you suppose it makes to a child—freedom, make-up-your-own-mind, I’m-not-going-to-put-any-pressure-on-you; and at the same time, the comrades, discipline, self-sacrifice, and kow-towing to authority…’

‘What you have to do is this,’ said Molly. ‘Find a place in one of your things that isn’t just share-pushing or promoting or money-making. See if you can’t find something constructive. Then show it to Tommy and let him decide.’

Richard, his face red with anger over his too-yellow, too-tight shirt, held a glass of whisky between two hands, turning it round and round, looking down into it. ‘Thanks,’ he said at last, ‘I will.’ He spoke with such a stubborn confidence in the quality of what he was going to offer his son, that Anna and Molly again raised their eyebrows at each other, conveying that the whole conversation had been wasted, as usual. Richard intercepted this glance, and said: ‘You two are so extraordinarily naive.’

‘About business?’ said Molly, with her loud jolly laugh.

‘About big business,’ said Anna quietly, amused, who had been surprised, during her conversations with Richard, to discover the extent of his power. This had not caused his image to enlarge, for her; rather he had seemed to shrink, against a background of international money. And she had loved Molly the more for her total lack of respect for this man who had been her husband, and who was in fact one of the financial powers of the country.

‘Ohhh,’ groaned Molly, impatient.

‘Very big business,’ said Anna laughing, trying to make Molly meet this, but the actress shrugged it off, with her characteristic big shrug of the shoulders, her white hands spreading out, palms out, until they came to rest on her knees.

‘I’ll impress her with it later,’ said Anna to Richard. ‘Or at least try to.’

‘What is all this?’ asked Molly.

‘It’s no good,’ said Richard, sarcastic, grudging, resentful. ‘Do you know that in all these years she’s never been interested enough even to ask?’

‘You’ve paid Tommy’s school fees, and that’s all I ever wanted from you.’

‘You’ve been putting Richard across to everyone for years as a sort of—well an enterprising little businessman, like a jumped-up grocer,’ said Anna. ‘And it turns out that all the time he’s a tycoon. But really. A big shot. One of the people we have to hate—on principle,’ Anna added laughing.

‘Really?’ said Molly, interested, regarding her former husband with mild surprise that this ordinary and—as far as she was concerned—not very intelligent man could be anything at all.

Anna recognized the look—it was what she felt—and laughed.

‘Good God,’ said Richard, ‘talking to you two, it’s like talking to a couple of savages.’

‘Why?’ said Molly. ‘Should we be impressed? You aren’t even self-made. You just inherited it.’

‘What does it matter? It’s the thing that matters. It may be a bad system, I’m not even going to argue—not that I could with either of you, you are both as ignorant as monkeys about economics, but it’s what runs this country.’

‘Well of course,’ said Molly. Her hands still lay, palms upward, on her knees. She now brought them together in her lap, in an unconscious mimicry of the gesture of a child waiting for a lesson.

‘But why despise it?’ Richard, who had obviously been meaning to go on, stopped, looking at those meekly mocking hands. ‘Oh Jesus!’ he said, giving up.

‘But we don’t. It’s too—anonymous—to despise. We despise…’ Molly cut off the word you, and as if in guilt at a lapse in manners, let her hands lose their pose of silent impertinence. She put them quickly out of sight behind her. Anna, watching, thought amusedly: If I said to Molly, you stopped Richard talking simply by making fun of him with your hands, she wouldn’t know what I meant. How wonderful to be able to do that, how lucky she is…

‘Yes, I know you despise me, but why? You’re a half-successful actress, and Anna once wrote a book?’

Anna’s hands instinctively lifted themselves from beside her, and fingers touching, negligent, on Molly’s knee, said, ‘Oh what a bore you are, Richard.’ Richard looked at them, and frowned.

‘That’s got nothing to do with it,’ said Molly.

‘Indeed.’

‘It’s because we haven’t given in,’ said Molly, seriously.

‘To what?’

‘If you don’t know we can’t tell you.’

Richard was on the point of exploding out of his chair—Anna could see his thigh muscles tense and quiver. To prevent a row she said quickly, drawing his fire: ‘That’s the point, you talk and talk, but you’re so far away from—what’s real, you never understand anything.’

She succeeded. Richard turned his body towards her, leaning forward so that she was confronted with his warm smooth brown arms, lightly covered with golden hair, his exposed brown neck, his brownish-red hot face. She shrank back slightly with an unconscious look of distaste, as he said: ‘Well, Anna, I’ve had the privilege of getting to know you better than I did before, and I can’t say you impress me with knowing what you want, what you think or how you should go about things.’

Anna, conscious that she was colouring, met his eyes with an effort, and drawled deliberately: ‘Or perhaps what it is you don’t like is that I do know what I want, have always been prepared to experiment, never pretend to myself the second-rate is more than it is, and know when to refuse. Hmmmm?’

Molly, looking quickly from one to the other, let out her breath, made an exclamation with her hands, by dropping them apart, emphatically, on to her knees, and unconsciously nodded—partly because she had confirmed a suspicion and partly because she approved of Anna’s rudeness. She said, ‘Hey, what is this?’ drawling it out arrogantly, so that Richard turned from Anna to her. ‘If you’re attacking us for the way we live again, all I can say is, the less you say the better, what with your private life the way it is.’

‘I preserve the forms,’ said Richard, with such a readiness to conform to what they both expected of him, that they both, at the same moment, let out peals of laughter.

‘Yes, darling, we know you do,’ said Molly. ‘Well, how’s Marion? I’d love to know.’

For the third time Richard said, ‘I see you’ve discussed it,’ and Anna said: ‘I told Molly you had been to see me. I told her what I didn’t tell you—that Marion had been to see me.’

‘Well, let’s have it,’ said Molly.

‘Why,’ said Anna, as if Richard were not present, ‘Richard is worried because Marion is such a problem to him.’

‘That’s nothing new,’ said Molly, in the same tone.

Richard sat still, looking at the women in turn. They waited; ready to leave it, ready for him to get up and go, ready for him to justify himself. But he said nothing. He seemed fascinated by the spectacle of these two, dashingly hostile to him, a laughing unit of condemnation. He even nodded, as if to say: Well, go on.

Molly said: ‘As we all know, Richard married beneath him—oh, not socially of course, he was careful not to do that, but quote, she’s a nice ordinary woman unquote, though luckily with all those lords and ladies scattered around in the collateral branches of the family tree, so useful I’ve no doubt for the letterheads of companies.’

At this Anna let out a snort of laughter—the lords and ladies being so irrelevant to the sort of money Richard controlled. But Molly ignored the interruption and went on: ‘Of course practically all the men one knows are married to nice ordinary dreary women. So sad for them. As it happens, Marion is a good person, not stupid at all, but she’s been married for fifteen years to a man who makes her feel stupid…’

‘What would they do, these men, without their stupid wives?’ sighed out Anna.

‘Oh, I simply can’t think. When I really want to depress myself, I think of all the brilliant men I know, married to their stupid wives. Enough to break your heart, it really is. So there is stupid ordinary Marion. And of course Richard was faithful to her just as long as most men are, that is, until she went into the nursing home for her first baby.’

‘Why do you have to go so far back?’ exclaimed Richard involuntarily, as if this had been a serious conversation, and again both women broke into fits of laughter.

Molly broke it, and said seriously, but impatiently: ‘Oh hell, Richard, why talk like an idiot? You do nothing else but feel sorry for yourself because Marion is your Achilles heel, and you say why go so far back?’ She snapped at him, deadly serious, accusing: ‘When Marion went into the nursing home.’

‘It was thirteen years ago,’ said Richard, aggrieved.

‘You came straight over to me. You seemed to think I’d fall into bed with you, you were even all wounded in your masculine pride because I wouldn’t. Remember? Now we free women know that the moment the wives of our men friends go into the nursing home, dear Tom, Dick and Harry come straight over, they always want to sleep with one of their wives’ friends, God knows why, a fascinating psychological fact among so many, but it’s a fact. I wasn’t having any, so I don’t know who you went to…’

‘How do you know I went to anyone?’

‘Because Marion knows. Such a pity how these things get round. And you’ve had a succession of girls ever since, and Marion has known about them all, since you have to confess your sins to her. There wouldn’t be much fun in it, would there, if you didn’t?’

Richard made a movement as if to get up and go—Anna saw his thigh muscles tense, and relax. But he changed his mind and sat still. There was a curious little smile pursing his mouth. He looked like a man determined to smile under the whip.

‘In the meantime Marion brought up three children. She was very unhappy. From time to time you let it drop that perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad if she got herself a lover—even things up a bit. You even suggested she was such a middle-class woman, so tediously conventional…’ Molly paused at this, grinning at Richard. ‘You are really such a pompous little hypocrite,’ she said, in an almost friendly voice. Friendly with a sort of contempt. And again Richard moved his limbs uncomfortably, and said, as if hypnotized, ‘Go on.’ Then, seeing that this was rather asking for it, he said hastily: ‘I’m interested to hear how you’d put it.’

‘But surely not surprised?’ said Molly. ‘I can’t remember ever concealing what I thought of how you treated Marion. You neglected her except for the first year. When the children were small she never saw you. Except when she had to entertain your business friends and organize posh dinner parties and all that nonsense. But nothing for herself. Then a man did get interested in her, and she was naive enough to think you wouldn’t mind—after all, you had said often enough, why don’t you get yourself a lover, when she complained of your girls. And so she had an affair and all hell let loose. You couldn’t stand it, and started threatening. Then he wanted to marry her and take the three children, yes, he cared for her that much. But no. Suddenly you got all moral, rampaging like an Old Testament prophet.’

‘He was too young for her, it wouldn’t have lasted.’

‘You mean, she might have been unhappy with him? You were worried about her being unhappy?’ said Molly, laughing contemptuously. ‘No, your vanity was hurt. You worked really hard to make her in love with you again, it was all jealous scenes and love and kisses until that moment she broke it off with him finally. And the moment you had her safe, you lost interest and went back to the secretaries on the fancy divan in your beautiful big business office. And you think it’s so unjust that Marion is unhappy and makes scenes and drinks more than is good for her. Or perhaps I should say, more than is good for the wife of a man in your position. Well, Anna, is there anything new since I left a year ago?’

Richard said angrily: ‘There’s no need to make bad theatre of it.’ Now that Anna was coming in, and it was no longer a battle with his former wife, he was angry.

‘Richard came to ask me if I thought it was justified for him to send Marion away to some home or something. Because she was such a bad influence on the children.’

Molly drew in her breath. ‘You didn’t, Richard?’

‘No. But I don’t see why it’s so terrible. She was drinking heavily about that time and it’s bad for the boys. Paul—he’s thirteen now, after all, found her one night when he got up for a drink of water, he found her unconscious on the floor, tight.’

‘You were really thinking of sending her away?’ Molly’s voice had gone blank, empty even of condemnation.

‘All right, Molly, all right. But what would you do? And you needn’t worry—your lieutenant here was as shocked as you are, Anna made me feel as guilty as you like.’ He was half-laughing again, though ruefully. ‘And actually, when I leave you I ask myself if I really do deserve such total disapproval? You exaggerate so, Molly. You talk as if I’m some sort of Bluebeard. I’ve had half a dozen unimportant affairs. So do most of the men I know who have been married any length of time. Their wives don’t take to drink.’

‘Perhaps it would have been better if you had in fact chosen a stupid and insensitive woman?’ suggested Molly. ‘Or you shouldn’t have always let her know what you were doing? Stupid! She’s a thousand times better than you are.’

‘It goes without saying,’ said Richard. ‘You always take it for granted that women are better than men. But that doesn’t help me much. Now look here, Molly, Marion trusts you. Please see her as soon as you can, and talk to her.’

‘Saying what?’

‘I don’t know. I don’t care. Anything. Call me names if you like, but see if you can stop her drinking.’

Molly sighed, histrionically, and sat looking at him, a look of half-compassionate contempt around her mouth.

‘Well I really don’t know,’ she said at last. ‘It is really all very odd. Richard, why don’t you do something? Why don’t you try to make her feel you like her, at least? Take her for a holiday or something?’

‘I did take her with me to Italy.’ In spite of himself, his voice was full of resentment at the fact he had had to.

‘Richard,’ said both women together.

‘She doesn’t enjoy my company,’ said Richard. ‘She watched me all the time—I can see her watching me all the time, for me to look at some woman, waiting for me to hang myself. I can’t stand it.’

‘Did she drink while you were on holiday?’

‘No, but…’

‘There you are then,’ said Molly, spreading out her flashing white hands, which said, What more is there to say?

‘Look here, Molly, she didn’t drink because it was a kind of contest, don’t you see that? Almost a bargain—I won’t drink if you don’t look at girls. It drove me nearly around the bend. And after all, men have certain practical difficulties—I’m sure you two emancipated females will take this in your stride, but I can’t make it with a woman who’s watching me like a jailor…getting into bed with Marion after one of those lovely holiday afternoons was like an I’ll-dare-you-to-prove-yourself contest. In short, I couldn’t get a hard on with Marion. Is that clear enough for you? And we’ve been back for a week. So far she’s all right. I’ve been home every evening, like a dutiful husband, and we sit and are polite with each other. She’s careful not to ask me what I’ve been doing or who I’ve been seeing. And I’m careful not to watch the level in the whisky bottle. But when she’s not in the room I look at the bottle, and I can hear her brain ticking over, he must have been with some woman because he doesn’t want me. It’s hell, it really is. Well all right,’ he cried, leaning forward, desperate with sincerity, ‘all right, Molly. But you can’t have it both ways. You two go on about marriage, well you may be right. You probably are. I haven’t seen a marriage yet that came anywhere near what it’s supposed to be. All right. But you’re careful to keep out of it. It’s a hell of an institution, I agree. But I’m involved in it, and you’re preaching from some pretty safe sidelines.’

Anna looked at Molly, very dry. Molly raised her brows and sighed.

‘And now what?’ said Richard, good-humoured.

‘We are thinking of the safety of the sidelines,’ said Anna, meeting his good-humour.

‘Come off it,’ said Molly. ‘Have you got any idea of the sort of punishment women like us take?’

‘Well,’ said Richard, ‘I don’t know about that, and frankly, it’s your own funeral, why should I care? But I know there’s one problem you haven’t got—it’s a purely physical one. How to get an erection with a woman you’ve been married to fifteen years?’

He said this with an air of camaraderie, as if offering his last card, all the chips down.

Anna remarked, after a pause, ‘Perhaps it might be easier if you had ever got into the habit of it?’

And Molly came in with: ‘Physical you say? Physical? It’s emotional. You started sleeping around early in your marriage because you had an emotional problem, it’s nothing to do with physical.’

‘No? Easy for women.’

‘No, it’s not easy for women. But at least we’ve got more sense than to use words like physical and emotional as if they didn’t connect.’

Richard threw himself back in his chair and laughed. ‘AH right,’ he said at last. ‘I’m in the wrong. Of course. All right. I might have known. But I want to ask you two something, do you really think it’s all my fault? I’m the villain as far as you are concerned. But why?’

‘You should have loved her,’ said Anna, simply.

‘Yes,’ said Molly.

‘Good Lord,’ said Richard, at a loss. ‘Good Lord. Well I give up. After all I’ve said—and it hasn’t been easy, mind you…’ he said this almost threatening, and went red as both women rocked off into fresh peals of laughter. ‘No, it’s not easy to talk frankly about sex to women.’

‘I can’t imagine why not, it’s hardly a great new revelation, what you’ve said,’ said Molly.

‘You’re such a…such a pompous ass,’ said Anna. ‘You bring out all this stuff, as if it were the last revelation from some kind of oracle. I bet you talk about sex when you’re alone with a popsy. So why put on this club-man’s act just because there are two of us?’

Molly said quickly: ‘We still haven’t decided about Tommy.’

There was a movement outside the door, which Anna and Molly heard, but Richard did not. He said, ‘All right, Anna, I bow to your sophistication. There’s no more to be said. Right. Now I want you two superior women to arrange something. I want Tommy to come and stay with me and Marion. If he’ll condescend to. Or doesn’t he like Marion?’

Molly lowered her voice and said, looking at the door, ‘You needn’t worry. When Marion comes to see me, Tommy and she talk for hours and hours.’

There was another sound, like a cough, or something being knocked. The three sat silent as the door opened and Tommy came in.

It was not possible to guess whether he had heard anything or not. He greeted his father first, carefully: ‘Hullo, father,’ nodded at Anna, his eyes lowered against a possible reminder from her that the last time they met he had opened himself to her sympathetic curiosity, and offered his mother a friendly but ironic smile. Then he turned his back on them, to arrange for himself some strawberries remaining in the white bowl, and with his back still turned enquired: ‘And how is Marion?’

So he had heard. Anna thought that she could believe him capable of standing outside the door to listen. Yes, she could imagine him listening with precisely the same detached ironic smile with which he had greeted his mother.

Richard, disconcerted, did not reply, and Tommy insisted: ‘How is Marion?’

‘Fine,’ said Richard, heartily. ‘Very well indeed.’

‘Good. Because when I met her for a cup of coffee yesterday she seemed in a pretty bad way.’

Molly raised swift eyebrows towards Richard, Anna made a small grimace, and Richard positively glared at both of them, saying the whole situation was their fault.

Tommy, continuing not to meet their eyes, and indicating with every line of his body that they underestimated his comprehension of their situations and the implacability of his judgement on them, sat down, and slowly ate strawberries. He looked like his father. That is to say he was a closely-welded, round youth, dark, like his father, with not a trace of Molly’s dash and vivacity. But unlike Richard, whose tenacious obstinacy was open, smouldering in his dark eyes and displayed in every impatient efficient movement, Tommy had a look of being buttoned in, a prisoner of his own nature. He was wearing, this morning, a scarlet sweat shirt and loose blue jeans, but would have looked better in a sober business suit. Every movement he ever made, every word he said, seemed in slow motion. Molly had used to complain, humorously, of course, that he sounded like someone who had taken an oath to count ten before he spoke. And she had complained, humorously, one summer when he had grown a beard, that he looked as if he had glued the rakish beard on to his solemn face. She had continued to make these loud, jolly complaints until Tommy had remarked: ‘Yes, I know you’d rather I looked like you—been attractive I mean. But it’s bad luck, I’ve got your character, and it should have been the other way around—well surely, if I’d had your looks and my father’s character—well, his staying power, at any rate, it would have been better?’—he had persisted with it, doggedly, as he did when trying to make her see a point that she was being wilfully obtuse about. Molly had worried about this for some days, even ringing Anna up: ‘Isn’t it awful, Anna? Who would have believed it? You think something for years, and come to terms with it, and then suddenly, they come out with something and you see they’ve been thinking it too?’

‘But surely you wouldn’t want him to be like Richard?’

‘No, but he’s right about the staying power. And the way he came out with it—it’s bad luck I’ve got your character, he said.’

Tommy ate his strawberries until there were none left, berry after berry. He did not speak, and neither did they. They sat watching him eat, as if he had willed them to do this. He ate carefully. His mouth moved in the act of eating as it did in the act of speaking, every word separate, each berry whole and separate. And he frowned steadily, his soft dark brows knitted, like a small boy’s over lessons. His lips even made small preliminary movements before a mouthful, like an old person’s. Or like a blind man, thought Anna, recognizing the movement; once she had sat opposite a blind man on the train. So had his mouth been set, rather full and controlled, a soft, self-absorbed pout. And so had his eyes been, like Tommy’s even when he was looking at someone: as if turned inwards on himself. Though of course he was blind. Anna felt a small rising hysteria, as she had sitting opposite the blind man, looking at the sightless eyes that seemed as if they were clouded with introspection. And she knew that Richard and Molly felt the same; they were frowning and making restless nervous movements. He’s bullying us all, thought Anna, annoyed; he’s bullying us horribly. And again she imagined how he had stood outside the door, listening, probably for a long time; she was by now unfairly convinced of it, and disliking the boy, because of how he was willing them to sit and wait for his pleasure.

Anna was just forcing herself, against a most extraordinary prohibition, emanating from Tommy, to say something, to break the silence, when Tommy laid down his plate, and the spoon neatly across it, and said calmly: ‘You three have been discussing me again.’

‘Of course not,’ said Richard, hearty and convincing.

‘Of course,’ said Molly.

Tommy allowed them both a tolerant smile, and said: ‘You’ve come about a job in one of your companies. Well I did think it over, as you suggested, but I think if you don’t mind I’ll turn it down.’

‘Oh Tommy,’ said Molly, in despair.

‘You’re being inconsistent, mother,’ said Tommy, looking towards her, but not at her. He had this way of directing his gaze towards someone, but maintaining an inward-seeming stare. His face was heavy, almost stupid-looking, with the effort he was making to give everyone their due. ‘You know it’s not just a question of taking a job, is it? It means I’ve got to live like them.’ Richard shifted his legs and let out an explosive breath, but Tommy continued: ‘I don’t mean any criticism, father.’

‘If it’s not a criticism, what is it?’ said Richard, laughing angrily.

‘Not a criticism, just a value judgement,’ said Molly, triumphant.

‘Ah, hell,’ said Richard.

Tommy ignored them, and continued to address the part of the room in which his mother was sitting.

‘The thing is, for better or for worse, you’ve brought me up to believe in certain things, and now you say I might just as well go and take a job in Portmain’s. Why?’

‘You mean,’ said Molly, bitter with self-reproach, ‘why don’t I offer you something better?’

‘Perhaps there isn’t anything better. It’s not your fault—I’m not suggesting it is.’ This was said with a soft, deadly finality, so that Molly frankly and loudly sighed, shrugged and spread out her hands.

‘I wouldn’t mind being like your lot, it’s not that. I’ve been around listening to your friends for years and years now, you all of you seem to be in such a mess, or think you are even if you’re not,’ he said, knitting his brows, and bringing out every phrase after careful thought, ‘I don’t mind that, but it was an accident for you, you didn’t say to yourselves at some point: I am going to be a certain kind of person. I mean, I think that for both you and Anna there was a moment when you said, and you were even surprised, Oh, so I’m that kind of person, am I?’

Anna and Molly smiled at each other, and at him, acknowledging it was true.

‘Well then,’ said Richard jauntily. ‘That’s settled. If you don’t want to be like Anna and Molly, there’s the alternative.’

‘No,’ said Tommy. ‘I haven’t explained myself, if you can say that. No.’

‘But you’ve got to do something,’ cried Molly, not at all humorous, but sounding sharp and frightened.

‘You don’t,’ said Tommy, as if it were self-evident.

‘But you’ve just said you didn’t want to be like us,’ said Molly.

‘It’s not that I wouldn’t want to be, but I don’t think I could.’ Now he turned to his father, in patient explanation. ‘The thing about mother and Anna is this; one doesn’t say, Anna Wulf the writer, or Molly Jacobs the actress—or only if you don’t know them. They aren’t—what I mean is—they aren’t what they do; but if I start working with you, then I’ll be what I do. Don’t you see that?’

‘Frankly, no.’

‘What I mean is, I’d rather be…’ he floundered, and was silent a moment, moving his lips together, frowning. ‘I’ve been thinking about it because I knew I’d have to explain it to you.’ He said this patiently, quite prepared to meet his parents’ unjust demands. ‘People like Anna or Molly and that lot, they’re not just one thing, but several things. And you know they could change and be something different. I don’t mean their characters would change, but they haven’t set into a mould. You know if something happened in the world, or there was a change of some kind, a revolution or something…’ He waited, a moment, patiently, for Richard’s sharply irritated indrawn breath over the word revolution, to be expelled, and went on: ‘they’d be something different if they had to be. But you’ll never be different, father. You’ll always have to live the way you do now. Well I don’t want that for myself,’ he concluded, allowing his lips to set, pouting over his finished explanation.

‘You’re going to be very unhappy,’ said Molly, almost moaning it.

‘Yes, that’s another thing,’ said Tommy. ‘The last time we discussed everything, you ended by saying, Oh, but you’re going to be unhappy. As if it’s the worst thing to be. But if it comes to unhappiness, I wouldn’t call either you or Anna happy people, but at least you’re much happier than my father. Let alone Marion.’ He added the last softly, in direct accusation of his father.

Richard said, hotly, ‘Why don’t you hear my side of the story, as well as Marion’s?’

Tommy ignored this, and went on: ‘I know I must sound ridiculous. I knew before I even started I was going to sound naïve.’

‘Of course you’re naïve,’ said Richard.

‘You’re not naïve,’ said Anna.

‘When I finished talking to you last time, Anna, I came home and I thought, Well, Anna must think I’m terribly naïve.’

‘No, I didn’t. That’s not the point. What you don’t seem to understand is, we’d like you to do better than we have done.’

‘Why should I?’

‘Well perhaps we might still change and be better,’ said Anna, with deference towards youth. Hearing the appeal in her own voice she laughed and said, ‘Good Lord, Tommy, don’t you realize how judged you make us feel?’

For the first time Tommy showed a touch of humour. He really looked at them, first at her, and then at his mother, smiling. ‘You forget that I’ve listened to you two talk all my life. I know about you, don’t I? I do think that you are both rather childish sometimes, but I prefer that to…’ He did not look at his father, but left it.

‘It’s a pity you’ve never given me a chance to talk,’ said Richard, but with self-pity; and Tommy reacted by a quick, dogged withdrawal away from him. He said to Anna and Molly, ‘I’d rather be a failure, like you, than succeed and all that sort of thing. But I’m not saying I’m choosing failure. I mean, one doesn’t choose failure, does one? I know what I don’t want, but not what I do want.’

‘One or two practical questions,’ said Richard, while Anna and Molly wryly looked at the word failure, used by this boy in exactly the same sense they would have used it. All the same, neither had applied it to themselves—or not so pat and final, at least.

‘What are you going to live on?’ said Richard.

Molly was angry. She did not want Tommy flushed out of the safe period of contemplation she was offering him by the fire of Richard’s ridicule.

But Tommy said: ‘If mother doesn’t mind I don’t mind living off her for a bit. After all, I hardly spend anything. But if I have to earn money, I can always be a teacher.’

‘Which you’ll find a much more straitened way of life than what I’m offering you,’ said Richard.

Tommy was embarrassed. ‘I don’t think you really understood what I’m trying to say. Perhaps I didn’t say it right.’

‘You’re going to become some sort of a coffee-bar bum,’ said Richard.

‘No. I don’t see that. You only say that because you only like people who have a lot of money.’

Now the three adults were silent. Molly and Anna because the boy could be trusted to stand up for himself; Richard because he was afraid of unleashing his anger. After a time Tommy remarked: ‘Perhaps I might try to be a writer.’

Richard let out a groan. Molly said nothing, with an effort. But Anna exclaimed: ‘Oh Tommy, and after all that good advice I gave you.’

He met her with affection, but stubbornly: ‘You forget, Anna, I don’t have your complicated ideas about writing.’

‘What complicated ideas?’ asked Molly sharply.

Tommy said to Anna: ‘I’ve been thinking about all the things you said.’

‘What things?’ demanded Molly.

Anna said: ‘Tommy, you’re frightening to know. One says something and you take it all up so seriously.’

‘But you were serious?’

Anna suppressed an impulse to turn it off with a joke, and said: ‘Yes, I was serious.’

‘Yes, I know you were. So I thought about what you said. There was something arrogant in it.’

‘Arrogant?’

‘Yes, I think so. Both the times I came to see you, you talked, and when I put together all the things you said, it sounds to me like arrogance. Like a kind of contempt.’

The other two, Molly and Richard, were now sitting back, smiling, lighting cigarettes, being excluded, exchanging looks.

But Anna, remembering the sincerity of this boy’s appeal to her, had decided to jettison even her old friend Molly, for the time being at least.

‘If it sounded like contempt, then I don’t think I can have explained it right.’

‘Yes. Because it means you haven’t got confidence in people. I think you’re afraid.’

‘What of?’ asked Anna. She felt very exposed, particularly before Richard, and her throat was dry and painful.

‘Of loneliness. Yes I know that sounds funny, for you, because of course you choose to be alone rather than to get married for the sake of not being lonely. But I mean something different. You’re afraid of writing what you think about life, because you might find yourself in an exposed position, you might expose yourself, you might be alone.’

‘Oh,’ said Anna, bleakly. ‘Do you think so?’

‘Yes. Or if you’re not afraid, then it’s contempt. When we talked about politics, you said the thing you’d learned from being a communist was that the most terrible thing of all was when political leaders didn’t tell the truth. You said that one small lie could spread into a marsh of lies and poison everything—do you remember? You talked about it for a long time…well then. You said that about politics. But you’ve got whole books you’ve written for yourself which no one ever sees. You said you believed that all over the world there were books in drawers, that people were writing for themselves—and even in countries where it isn’t dangerous to write the truth. Do you remember, Anna? Well, that’s a sort of contempt.’ He had been looking, not at her, but directing towards her an earnest, dark, self-probing stare. Now he saw her flushed, stricken face, but he recovered himself, and said hesitantly: ‘Anna, you were saying what you really thought, weren’t you?’

‘Yes.’

‘But Anna, you surely didn’t expect me not to think about what you said?’

Anna closed her eyes a moment, smiling painfully. ‘I suppose I underestimated—how much you’d take me seriously.’

‘That’s the same thing. It’s the same thing as the writing. Why shouldn’t I take you seriously?’

‘I didn’t know Anna was writing at all, these days,’ said Molly, coming in firmly.

‘I don’t,’ said Anna, quickly.

‘There you are,’ said Tommy. ‘Why do you say that?’

‘I remember telling you that I’d been afflicted with an awful feeling of disgust, of futility. Perhaps I don’t like spreading those emotions.’

‘If Anna’s been filling you full of disgust for the literary career,’ said Richard, laughing, ‘then I won’t quarrel with her for once.’

It was a note so false that Tommy simply ignored him, which he did by politely controlling his embarrassment and going straight on: ‘If you feel disgust, then you feel disgust. Why pretend not? But the point is, you were talking about responsibility. That’s what I feel too—people aren’t taking responsibility for each other. You said the socialists had ceased to be a moral force, for the time, at least, because they wouldn’t take moral responsibility. Except for a few people. You said that, didn’t you—well then. But you write and write in notebooks, saying what you think about life, but you lock them up, and that’s not being responsible.’

‘A very great number of people would say that it was irresponsible to spread disgust. Or anarchy. Or a feeling of confusion.’ Anna said this half-laughing, plaintive, rueful, trying to make him meet her on this note.

And he reacted immediately, by closing up, sitting back, showing she had failed him. She, like everyone else—so his patient, stubborn pose suggested, was bound to disappoint him. He retreated into himself, saying: ‘Anyway, that’s what I came down to say. I’d like to go on doing nothing for a month or two. After all it’s costing much less than going to university as you wanted.’

‘Money’s not the point,’ said Molly.

‘You’ll find that money is the point,’ said Richard. ‘When you change your mind, ring me up.’

‘I’ll ring you up in any case,’ said Tommy, giving his father his due.

‘Thanks,’ said Richard, short and bitter. He stood for a moment, grinning angrily at the two women. ‘I’ll drop in one of these days, Molly.’

‘Any time,’ said Molly, with sweetness.

He nodded coldly at Anna, laid his hand briefly on his son’s shoulder, which was unresponsive, and went out. At once Tommy got up, and said: ‘I’ll go up to my room.’ He walked out, his head poked forward, a hand fumbling at the door-knob, the door opened just far enough to take his width: he seemed to squeeze himself out of the room; and they heard his regular thumping footsteps up the stairs.

‘Well; said Molly.

‘Well,’ said Anna, prepared to be challenged.

‘It seems a lot of things have been going on while I was away.’

‘For one thing, it seems I said things to Tommy I shouldn’t.’

‘Or not enough.’

Anna said with an effort: ‘Yes I know you want me to talk about artistic problems and so on. But for me it’s not like that…’ Molly merely waited, looking sceptical, and even bitter. ‘If I saw it in terms of an artistic problem, then it’d be easy, wouldn’t it? We could have ever such intelligent chats about the modem novel.’ Anna’s voice was full of irritation, and she tried smiling to soften it.

‘What’s in those diaries then?’

‘They aren’t diaries.’

‘Whatever they are.’

‘Chaos, that’s the point.’

Anna sat watching Molly’s thick white fingers twist together and lock. The hands were saying: Why do you hurt me like this?—but if you insist then I’ll endure it.

‘If you wrote one novel, I don’t see why you shouldn’t write another,’ said Molly, and Anna began to laugh, irresistibly, while her friend’s eyes filled with sudden tears.

‘I wasn’t laughing at you.’

‘You simply don’t understand,’ said Molly, determinedly muffling the tears, ‘It’s always meant so much to me that you should produce something, even if I didn’t.’