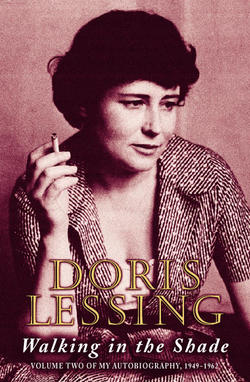

Читать книгу Walking in the Shade: Volume Two of My Autobiography, 1949 -1962 - Doris Lessing - Страница 8

CHURCH STREET, KENSINGTON W8

ОглавлениеTHE HOUSE NEAR THE PORTOBELLO ROAD was war-damaged and surrounded by areas of bombed buildings. The house in Church Street had been war-damaged, and near it were war ruins. Bonfires often burned on the bomb sites, to get rid of the corpses of houses. Otherwise the two houses had nothing in common. In the house I had left, politics had meant food and rationing and the general stupidities of government, but in Church Street I was returned abruptly to international politics, communists, the comrades, passionate polemic, and the rebuilding of Britain to some kind of invisible blueprint, which everyone shared. Joan Rodker worked for the Polish Institute, was a communist, if not a Party member, and knew everyone in ‘the Party’ – which is how it was referred to – and knew, too, most people in the arts. Her story is extraordinary and deserves a book or two. She was the daughter of two remarkable people, from the poor but vibrant East End, when it was still supplying the arts, and intellectual life generally, with talent. Her father was John Rodker, a writer and a friend of the well-known writers and intellectuals of that time, who mysteriously did not fulfil the expectations everyone had for him and became a publisher. Her mother was a beauty who sat for the artists, notably Isaac Rosenberg. They dumped Joan as a tiny child in an institution that existed to care for the children of people whose lives could not include children. It was a cruel place, though in outward appearance genteel. Her parents intermittently visited but never knew what the little girl was enduring. Surviving all this, and much else, she was acting in a theatre company in the Ukraine, having easily learned German and Russian, being endowed with that kind of talent, when she had a child by a German actor in the company. Since bourgeois marriage had been written out of history for ever, they did not marry. She was instrumental in getting him out of Czechoslovakia and into England before the war began. I used his appearance in Children of Violence, in the place of Gottfried Lessing, because I thought, This is Peter’s father. One man was middle class, the other rich, very rich, from Germany’s decadent time. My substitution of one man for another did not have the effect intended. Gottfried said I had put him in the book, yet all the two characters had in common was being German and communist. That could only mean Gottfried thought that what identified him was his politics. Hinze, a well-known actor, was around while Ernest – Joan’s child – was growing up, helping with money and with time. He, too, was a remarkable man, and his story deserves to be recorded. Hard times do produce extraordinary people. I don’t know what the practical application of that thought could be.

Joan returned to London after the war, from America, with the child – and found she had nowhere to live. She saw this house, in Church Street, open to the sky, and thought. That’s my house. She brought in buckets of water and began scrubbing down the rooms, night after night, when she had done with work. War Damage sent in workmen to repair the house and found Joan on her knees, with a scrubbing brush.

‘What you doing?’

‘Cleaning my house,’ she said.

‘But it isn’t your house.’

‘Yes it is.’

‘You’d better have documents to prove it, then.’

She had no money. She went to her father and demanded that he guarantee a bank loan. He was disconcerted; people who have had to drag themselves up from an extreme of poverty may take a long time to see themselves as advantaged. With a guaranteed bank loan, and her determination, she got her house, where she is living to this day.

All these vicissitudes had given her an instinct for the distress of others which was the swiftest and surest I have known. She knew how to help people. Her kindness, her generosity, was not sentimental but practical and imaginative. I had plenty of people to compare her with, because I was meeting people who had survived war, prison camps, every kind of disaster; my life was full of survivors, but not all of them had been improved by what had happened to them.

Peter had been happy in the other house, and he enjoyed this one as much. Joan’s son, Ernest, then adolescent, was as wonderfully kind as Joan herself. He was like an elder brother. People who have brought up small children without another parent to share the load will know I have said the most important thing about my life then.

If living in the other house was as strange to me as if I’d been immersed in a Victorian novel, life in Church Street, Kensington, was only a continuation of that flat in Salisbury where people dropped in day and night for cups of tea, food, argument, and often noisy debate. Going up or down the stairs, I passed the open door into the little kitchen, often crammed with comrades, having a snack, talking, shouting, or imparting news in confidential tones, for a great deal was going on in the communist world which was discussed in lowered voices and never admitted publicly. I was again in an atmosphere that made every encounter, every conversation, important, because if you were a communist, then the future of the world depended on you – you and your friends and people like you all over the world. The vanguard of the working class, in short. I was in conflict. Having lived with Gottfried Lessing, a ‘one hundred and fifty percenter’ – a phrase used at that time in communist circles – I was weary of dogmatism and self-importance. When I was with Gottfried, who was now at the nadir of his life and, because of his low spirits, even more violently rude about people and opinions not communist, I was seeing a mirror of myself – a caricature, yes, but true. A line from Gerald Manley Hopkins haunted me.

This, by Despair, bred Hangdog dull; by Rage, Manwolf, worse; and their packs infest the age.

I would wake out of a dream, muttering, ‘“and their packs infest the age”’. Me: Hopkins was talking about me.

I lived in a pack, was one of a pack. But when the comrades came up the stairs to the top of the house – and they often did, for up there lived a lively young woman and her delightful little boy, an exotic too, coming from Africa, which seemed always to be in the news these days – I found people interested in what I said about South Africa and Southern Rhodesia. Anywhere outside communist circles, my information that Southern Rhodesia was not a paradise of happy darkies was greeted with impatience. You are so wrong-headed, those looks said. How patronized I have been by people who don’t want to know. But the comrades did want to know. An attraction of Communist Party circles was that if you happened to remark, ‘I have been in Peru, and …’ people wanted to know. The world was their responsibility. I was finding this increasingly ridiculous, but the thing wasn’t so easy. I looked back to Salisbury, where we had assumed, for years, that what we did and thought was of world-shattering (literally) significance, but from the perspectives of London our little group there seemed embarrassing, absurd – yet I knew that these absurd people were the few, in all of white Southern Rhodesia, who understood the truth about the white regime: that it was doomed, could not last long. It was not our views but our effectiveness that was in question. And here I was again, being part of a minority, and a very small one, who knew they were in the right. This was the height of the Cold War. The Korean War had started. The communists were with every day more isolated. The atmosphere was poisonous. If, for instance, you doubted that America was dropping wads of material infected with germs – germ warfare – then you were a traitor. I was undermined with doubts. I hated this religious language, and I was not the only one. ‘Comrade So-and-so is getting doubts,’ a communist might say, with that sardonic intonation that was already – and would increasingly become – the tone of many conversations. But again, this was not simple, for it was certainly not only the comrades who identified with an idealized Soviet Union.

Although I was not a member of the Communist Party, I was accepted by the comrades as one of them: I spoke the language. When I protested that I had been a member of a communist party invented by us in Southern Rhodesia, which any real Communist Party would have dismissed with contempt, they did not care – or perhaps they did not hear. It has been my fate all my life often to be with people who assume I think as they do, because a passionate belief, or set of assumptions, is so persuasive to the holders of them that they really cannot believe anyone could be so wrong-headed as not to share them. I could not discuss any ‘doubts’ I might have with Joan or anyone who came to that house – not yet, but, if I found the Party Line hard to swallow, there was something else, much stronger. Colonials, the children or grandchildren of the far-flung Empire, arrived in England with expectations created by literature. ‘We will find the England of Shelley and Keats and Hopkins, of Dickens and Hardy and the Brontes and Jane Austen, we will breathe the generous airs of literature. We have been sustained in exile by the magnificence of the Word, and soon we will walk into our promised land.’ All the communists I met had been fed and sustained by literature, and very few of the other people I met had. In short, my experience in Southern Rhodesia continued, if modified, not least because again I was having to defend my right to write, to spend my time writing, and not to run around distributing pamphlets or the Daily Worker. But a woman who had stood up to Gottfried Lessing – ‘Why are you wasting your time? Writing is just bourgeois self-indulgence’ – was more than equipped to deal with the English comrades. The pressure on writers – and artists – to do something other than write, paint, make music, because those are nothing but bourgeois indulgences, continued strong, and continues now, though the ideologies are different, and will continue, because it has roots in envy, and the envious ones do not know they suffer from a disease, know only that they are in the right.

It did help that I was now one of the recognized new writers. The Grass Is Singing had got very good reviews, and was selling well, and was bought in other countries. The short stories, This Was the Old Chief’s Country, did well. Needless to say, I was attacked by the comrades for all kinds of ideological shortcomings. For instance, The Grass Is Singing was poisoned by Freud. At that stage I had not read much Freud. The short stories did not put the point of view of the organized black working class. True. For one thing, there wasn’t one. There is no way one can exaggerate the stupidity of communist literary criticism; any quote immediately seems like mockery or caricature – like so much of Political Correctness now.

It was not only pressures from my own side that I had to resist. For instance, the editor of a popular newspaper, the Daily Graphic – it was not unlike the Sun – long since defunct, invited me to his office and offered me a lot of money to write articles supporting hanging, the flogging of delinquent children, harsher treatment for criminals, a woman’s place in the home, down with socialism, internment for communists. When I said I disagreed with all these, the editor, a nasty little man, said it didn’t matter what my personal opinions were. If I wanted, I could be a journalist – he would train me – and journalists should know how to write persuasively on any subject. I kept refusing large sums of money, which got larger as he became more exasperated. I fled to a telephone in the street, where I rang up Juliet O’Hea. I needed money badly. She said on no account should I ever write one word I did not believe in, never write a word that wasn’t the best I could do; if I started writing for money, the next thing would be I’d start believing it was good, and neither of us wanted that, did we? She did not believe in asking for advances before they were due, but if I was desperate she would. And she would tell the editor of the Daily Graphic to leave me alone.

There were other offers on the same lines, temptations of the Devil. Not that I was really tempted. But I did linger sometimes in an editor’s office out of curiosity: I could not believe that this was happening, that people could be so low, so unscrupulous. But surely they can’t really believe writers should write against their own beliefs, their consciences? Write less than their best, for money?

The most bizarre result of The Grass Is Singing, which was being execrated in South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, was an invitation to be ‘one of the girls’ at an evening with visiting members of the still new Nationalist government. I was too intrigued to refuse, fascinated that Southern African customs could hold good here: ‘The English cricket team is coming – just round up some of the girls for them.’ There were ten or so Afrikaners, ministers or slightly lesser officials, living it up on a trip to London. I knew them all by name, and only too well as a type. Large, overfed, jovial, they joked their way through a restaurant dinner, about all the ways they used to keep the kaffirs down, for it was then a characteristic of these ruling circles to be proud of being ‘slim’ – full of cunning tricks. After dinner we repaired to a hotel bedroom, where I was in danger of being fondled by one or more. Another of ‘the girls’ told the men that I was an enemy and they should be careful of what they said. Why was I an enemy? was demanded, with the implicit suggestion that it was not possible to disagree with their evidently correct views. ‘She’s written a book,’ said this woman, or girl, a South African temporarily in London. ‘Then we’re going to ban it,’ was the jocular reply. One man, whose knee I was trying to refuse, said, ‘Ach, man, we don’t care what liberals read, what do they matter? The kaffirs aren’t going to read your little book. They can’t read, and that’s how we like it.’ The word ‘liberal’ in South Africa has always been interchangeable with ‘communist’.

All the places where I had lived with Gottfried, in Salisbury, people had dropped in and out, and the talk was not only of politics, and of changing the world, but of war; in Church Street it was the same, except that here war was not all rumour and propaganda but men who had returned from battlefronts, so that we could match what really had happened with what we had been told was happening. Similarly, I was in a familiar situation with Gottfried, who disapproved of me more with every meeting. He was having a very bad time. He had believed he would easily get a job in London. He knew himself to be clever and competent: had he not created a large and successful legal firm, virtually out of nothing, in Salisbury? There were relatives in London, to whom he applied for work. They turned him down. He was a communist, and they were – or felt themselves to be – on sufferance in Britain, as foreigners. Or perhaps they didn’t like him. He was applying for jobs on the level which he knew he deserved. No one would even give him an interview. The joke was, ten years later it would be chic to be German and a communist. Meanwhile he was working for the Society for Cultural Relations with the Soviet Union. This organization owned a house in Kensington Square, where there were lectures on the happy state of the arts in the USSR. At every meeting the two back rows of chairs were filled with people who had actually lived under communism: they were trying to tell us how horrible communism was. We patronized them: they were middle-aged or old, they didn’t know the score, they were reactionary. A well-chosen epithet, flattering to the user, is the surest way of ending all serious thought. Gottfried earned very little money. He was being sheltered by Dorothy Schwartz, who had a large flat near Belsize Park Underground. The height – or depth – of the Cold War made him even more bitterly, angrily, coldly contemptuous of any opinion even slightly deviating from the Party Line. I was finding it almost impossible to be with him. I did not say to myself, But how did I stick him for so long? For we had had no alternative. About the child there were no disagreements. Peter spent most weekends with Gottfried and Dorothy. I would take him over there, sit down, have a cup of this or that, and listen to terrible, cold denunciations, then leave for two days of freedom. I went to the theatre a lot. In those days you queued in the mornings for a stool in the queue for the evening and saw the play from pit or gallery for the equivalent in today’s money of three or four pounds. I saw most of the plays on in London, in this way, sometimes standing. I continued madly in love with the theatre.

I also went off to Paris. There is no way now of telling how powerful a dream France was then. The British – that is, people who were not in the forces – had been locked into their island for the war and for some years afterwards. People would say how they had suffered from claustrophobia, dreamed of abroad – and particularly of Paris. France was a magnet because of de Gaulle, and the Free French, and the Resistance, by far the most glamorous of the partisan armies. Now that our cooking and our coffee and our clothes are good, it is hard to remember how people yearned for France as for civilization itself. And there was another emotion too, among women. French men loved women and showed it, but in Britain the most women could hope for was to be whistled at by workmen in the street, not always a friendly thing. Joan adored France. She had spent happy times there and spoke French well. Her father’s current girlfriend was French. Joan saw her as infinitely beautiful, while she was a mere nothing in comparison. This was far from the truth, but there was no arguing with her. (This was certainly not the only time in my life I have known a woman who wore rose-tinted spectacles for every woman in the world but herself.) Isn’t she gorgeous, she would moan over some woman less attractive than she was. She had had a very smart black suit made, with a tight skirt and a waistcoat like a man’s, which she wore with white shirts ruffled at throat and wrists. She actually went over to Paris to get it judged. There, men would compliment you on your toilette. She came back restored. Quite a few women I knew said that for the sake of one’s self-respect one had to visit Paris from time to time. This was not a situation without its little ironies. There was a newspaper cartoon then of a Frenchman, dressed in semi-battle gear, old jacket, beret, a Gauloise hanging from a lip, accompanying a Frenchwoman dressed like a model – a short stocky scruffy man, a tall slim elegant woman.

When I went to Paris my toilette was hardly of the level to attract French compliments, but it was true every man gave you a quick, expert once-over – hair, face, what you were wearing – allotting you marks. This was a dispassionate, disinterested summing-up, not necessarily leading to invitations.

A scene: I took myself to the opera, and in the foyer, at the interval, saw enter a very young woman, eighteen, perhaps, in what was perhaps her first evening dress, a column of white satin. She was exquisite, and so was the dress. She stood poised just in the entrance, while the crowd looked … assessed … judged. Not a word, but they might as well have been clapping. She was at first ready to shrink away with shyness but slowly filled with confidence, stood smiling, tears in her eyes, lifted on invisible waves of expert appreciation, approval, love. Adorable France, which loves its women, gives them confidence in their femininity – and that from the time when they are tiny girls.

On this first trip I was in a cheap hotel on the Left Bank, so cheap I could hardly believe it. Gottfried had said I should look up his sister’s husband’s mother. I did and found an elderly lady in old-fashioned clothes living in a tiny room high up under the roof of one of those tall ancient cold houses. Through her I was admitted into a network of middle-aged and old women, without men, all poor, shabby, living from hand to mouth in maids’ rooms or in any comer that would let them fit themselves in. There they were, every one a victim of war, and some of them had lived in their little refuges through the war and, clearly, often did not know how they had managed it. They were witty and they were wise, and the best of company. As with the refugees in London then, it was hard to know what they lived on. I was served precious coffee in beautiful cups, by a stove that had to be fed with wood and coal – and whatever was burnable that could be picked up in the street, brought toiling up hundreds of cold stairs. Madame Gise had not heard from her son since the beginning of the war and said that he had chosen to despise her, because she was not a communist. She despised communists and communism. I said I was a kind of communist, and she said, Nonsense, you don’t know anything about it. These women, whose husbands or lovers or sons had been killed or had forgotten them: they were so brave, supporting each other in their poverty and when they were ill. Again, as in London, I was hearing tales of impossible survivals, endurances. Our talk in London of politics, all ideas and principles, of what went on in other countries, dissolved here into: ‘My cousin … Ravensbrook’; ‘My son was shot by the Germans for harbouring a member of the Resistance’; ‘I escaped from Germany … from Poland … from Russia … from Spain …’

In Paris I bought a hat. This needs explanation. I had to: it was a need of the times. A Paris hat proved you had captured elegance itself. Madame Gise stood by me. Saying, No, not that one, Yes, that one, she was representing Paris itself, that shabby woman with a carefully counted out store of francs in her handbag. I never wore the hat. But I owned a Paris hat. Joan said, But what are you going to do with it?

Another trip, and in another shabby hotel, I suddenly thought, But surely this was where Oscar Wilde died? Down I went to the desk, and the proprietress said. Yes, indeed that was so, he died here, and it was in the room you are in. People sometimes came to ask her about it, but she couldn’t say much; after all, she hadn’t been here. When I wanted to pay the bill, there was no one at the desk. I knocked at a door, and was told, Entrez. It was a dark, cluttered room, with mirrors gleaming from corners, shawls over chairs, a cat. There was Madame, in an armchair, flesh bulging over her pink corset, her fat feet in a basin of water. The maid, a young girl, was brushing her rusty old hair, while Madame tossed it back as if it were a treasure, in her imagination young tresses. This was a scene from Balzac? Zola? Certainly not a twentieth-century novel. Or Degas: The Concierge, perhaps? I lingered at the door, entranced. ‘Leave your money at the desk,’ she said. ‘The bill is there. And let us see you again, Madame.’ But I didn’t go back: one shouldn’t spoil perfection. And I didn’t see Madame Gise again either, and about that I feel bad.

On one of these trips there was one of the oddest encounters of my life. The plane back from Paris was delayed, by hours. At Orly we sat around, bored, tired, fractious. At last we were on. Next to me was a South African man, who, hearing from my voice that I was from Rhodesia, began talking. He was, I thought, drunk, then thought, No, that’s not drink. I hardly listened: We would land after midnight; I was years away from being able to afford taxis; Peter still woke at five. Slowly, what the man was saying began to penetrate. He was telling me that he had made a trip to Palestine to aid Irgun in its fight against the British occupying forces, and he had just helped to blow up the King David Hotel. Now, his duty as a Jew done, he was returning with a good conscience to South Africa. Women are used to hearing confessions, particularly if they are young – well, by then youngish – and reasonably attractive. Women don’t really count, as people, to a man who is drunk, or not himself for one reason or another – or to many men sober, if it comes to that. Suddenly it occurred to me that this was an enemy of my country and I should be thinking of how to alert the authorities. We landed. The airport was almost deserted. I was imagining what would happen if I said to the air hostess, I want to speak to the police. ‘What for?’ I could hear – and the voice would be tart, for she would be longing for bed, just like me. The police – a man, or two men – would arrive, after a delay, while I watched other people going off to find a bus. ‘I have been sitting on the plane from Paris next to a man who says he has been blowing up the King David Hotel. Among other things.’ The policeman hesitates. He glances at his partner. They examine me. My appearance, tired and cross, does not impress.

‘So this man told you he’d been blowing up this hotel?’

‘Yes.

‘Do you know him?’

‘No.’

‘So he was telling a perfect stranger that he had been committing murder and treason and God knows what in Jerusalem?’

‘Oh, forget it.’

But of course that would not be the end, and I’d have to hang around while sceptical officials questioned. If they didn’t decide I was simply daft.

‘There, there, just you run along home, dear, and forget all about it.’

The thing was – and is – I am sure he was telling the truth. Or – perhaps even more interesting – he had imagined it all so strongly, the blowing up of the hotel, the murder of policemen, that for him it was all true and had to be shared, even if only with a stranger in the next seat on an aeroplane.

I went to Dublin too, invited by writers, I am sure, for there was a convivial evening. But that is not what I remember most, what I cannot forget. I was just over a year out of all that sunlight, that dry heat, and I thought I had experienced everything in the way of dismalness and greyness in London, but suddenly I was in this city of old, unkempt buildings, and dignified, a city proud of itself, but everywhere ran about ragged children, with bare feet, legs red with cold, hungry faces. Never has there been such a poor place as Dublin then, and it was a sharp, biting poverty, which afflicted the writers too, for one of them pressed into my hands a book called Leaves for the Burning, unjustly forgotten, by Mervin Wall, the account of a drunken weekend, but this was the drinking of desperation. That city of rags and hunger had disappeared when I went again less than ten years later.

I reviewed Leaves for the Burning somewhere, probably John O’London’s Weekly. Now, that was an interesting periodical. It was the product of a now defunct culture, or sub-culture. All over Britain then, in towns, in villages, were groups of mostly young people, drawn together by love of literature. They read books, they discussed books, they met in pubs and in each other’s houses. Some of them aspired to write, but that was long before the time when anyone who had read a novel aspired to write one. John O’London was not highbrow, it was nowhere near the level of, let’s say, The London Review of Books now. But it had standards and was jealous of them, printed verses, had literary competitions – a pity there is nothing like it now. Another periodical served the short story: The Argosy. It was serious enough, within limits. It would not, for instance, print a story by Camus or a piece by Virginia Woolf, but I remember enjoyable tales. This, too, had a readership far beyond London; its real strength was provincial literary culture. Another lost and gone magazine was Lilliput, a lively compendium of tales, odd pieces, pictures. It was edited for a while by Patrick Campbell, who will be remembered now as the man who in spite of – you’d think – an incapacitating stammer was on television, in panel games. A story of mine went into Lilliput. On the strength of it we had several lunches in L’Escargot, long and alcoholic lunches, as were then a perk for both writer and editor. L’Escargot has gone through several transmutations, even an unfortunate one as nouvelle cuisine, but it was a mystery then that often we were the only people eating there at lunchtime. In the evenings it was crammed.

A visiting American said, did I read science fiction? I offered Olaf Stapledon, H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and he said it was a good beginning. Then he gave me an armful of science fiction novels. What I felt then I have felt ever since. I was excited by their scope, the wideness of their horizons, the ideas, and the possibilities for social criticism – particularly in this time of McCarthy, when the atmosphere was so thick and hostile to new ideas in the United States – and disappointed by the level of characterization and the lack of subtlety. My mentor said, But of course you can’t have subtlety of character, which depends on a cultural matrix, if the hero is pioneering engineer Dick Tantrix No. 65092 on the artificial planet Andromeda, Sector 25,000. Very well, but I have always felt that a sci-fi novel is yet to be written using density of characterization, like Henry James. It would be great comedy, for a start. But if what we do get is so wonderfully inventive and astonishing and mind-boggling, then why repine? In science fiction are some of the best stories of our time. To open a sci-fi novel, or to be with science fiction writers, if you’ve just come from a sojourn in the conventional literary world, is like opening windows into a stuffy and old-fashioned little room.

My new tutor said he would take me to a pub where science fiction writers went. He did. It must have been the White Horse in Fetter Lane, off Fleet Street. There was a room full of bespectacled lean men who turned as one to look warily at me – a masculine atmosphere. No, the word suggests a sexual lordliness. ‘Blokeish’, then? No, too homespun and ordinary. This was a clan, a group, a family, but without women. I felt I should not be there, though chaperoned by my American, whom they knew and welcomed. What they were was defensive: this was because they had been so thoroughly rejected by the literary world. They had the facetiousness, the jokiness, of their defensiveness. I babbled absurdly about Nietzsche’s Superman, and the Revelations, and they were embarrassed. I like to think the great Arthur C. Clarke was there, but he had probably left for the States by then.

My disappointment with what I thought of as a dull group of people, suburban, provincial, was my fault. In that prosaic room, in that very ordinary pub, was going on the most advanced thinking in this country. (The Astronomer Royal had said it would be ridiculous to think that we could send people to the moon.) What these men were talking about, thinking about, were satellite communications, rocketry, spacecraft and space travel, the social uses of television. They were linked with people like themselves across the world: ‘The Earth is the cradle of Mankind, but you cannot live in a cradle for ever.’ – Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. ‘We are living,’ said Arthur C. Clarke, ‘in a moment unique in all history – the last days of Man’s existence as a citizen of a single planet.’ My trouble was that I didn’t have mathematics, physics – couldn’t speak their language. Because of my ignorance, I know I have been cut off from the developments going on in science – and science is where our frontiers are, in this time. It is not to the latest literary novel that people now look for news about humanity, as they did in the nineteenth century.

When lists are made of the best British writers since the war, they do not include Arthur C. Clarke, nor Brian Aldiss, nor any of the good science fiction writers. It is conventional literature that has turned out to be provincial.

And so I had made a life for me and for Peter. That was an achievement, and I was proud of myself. The most important part was Peter, who was enjoying this life, particularly the nursery school, in Kensington, and then the family atmosphere with Joan and Ernest. Never has there been a child so ready to make friends. Our days still began at five. Again I was reading to him and telling him stories for a couple of hours after he woke, because Joan’s bedroom was immediately below, and the floors were thin, and she did not wake till later. Or he listened to the radio. We have forgotten the role radio played before television. Peter loved the radio. He listened to everything. He listened to two radio plays based on novels by Ivy Compton-Burnett, each an hour long, standing by the machine, absolutely riveted. What was he hearing? Understanding? I have no idea. It is my belief that children are full of understanding and know as much as and more than adults, until they are about seven, when they suddenly become stupid, like adults. At three or four, Peter understood everything, and at eight or nine read only comics. And I’ve seen this again and again with small children. A child of three sits entranced through the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, but four years later can tolerate only Rupert Bear.

I was writing Martha Quest, a conventional novel, though the demand then was for experimental novels. I played in my mind with a hundred ways of doing Martha Quest, pulling shapes about, playing with time, but at the end of all this, the novel was straightforward. I was dealing with my painful adolescence, my mother, all that anguish, the struggle for survival.

And now there arrived a letter from my mother, saying she was coming to London, she was going to live with me and help me with Peter, and – here was the inevitable, surreal, heartbreaking ingredient – she had taught herself typing and would be my secretary.

I collapsed. I simply went to bed and pulled the covers over my head. When I had taken Peter to nursery school, I crept away into the dark of my bed and stayed there until I had to bring him home.

And now – again–there is the question of time, tricksy time, and until I came to write this and was forced to do my work with calendars and obdurate dates, I had thought, vaguely, that I was in Denbigh Road for … well, it was probably three years or so. But that was because, having been returned to child seeing, everything new and immediate, I had been returned – well, partly – to child time. No matter how I wriggled and protested. No, it can’t have been only a year, it was a year before I went to Joan’s, and I had been there only six months or so when the letter came from my mother. Yet those months seem now like years. Time is different at different times in one’s life. A year in your thirties is much shorter than a child’s year – which is almost endless – but long compared with a year in your forties; whereas a year in your seventies is a mere blink.

Of course she was bound to come after me. How could I have been so naive as to think she wouldn’t, as soon as she could? She had been in exile in Southern Rhodesia, dreaming of London, and now … She and her daughter did not ‘get on,’ or, to put it truthfully, had always fought? Oh, never mind, the girl was wrong-headed; she would learn to listen to her mother. She was a communist? She always had disreputable friends? That was all right; her mother would introduce her to really nice people. She had written The Grass Is Singing, which had caused her mother anguish and shame, because it was so hated by the whites? And those extremely unfair short stories about The District? Well, she – the girl’s mother – would explain to everyone that no one outside the country could really understand the whites’ problems and … But the author had been brought up in the country? Her views were wrong, and in time she would come to see that … She proposed to live with a daughter who had broken up her first marriage, leaving two children, had married a German refugee at the height of the war, who was a kaffir-lover and scornful of religion?

Well, how did she see it? Now I believe she did not think about it much. She could not afford to. She longed to live in London again, but it was the London she had left in 1919. She had no friends left, except for Daisy Lane, with whom she had been exchanging letters, but Daisy Lane was now an old lady, living in Richmond with her sister, an ex-missionary from Japan. There was her brother’s family, and she was coming home in time for the daughter’s wedding. Her brother’s sister-in-law had already said, ‘I hope Jane doesn’t imagine she is going to take first place at the wedding.’ (Jane: Plain Jane, the loving family nickname, making sure that Maude didn’t imagine she possessed any attractions.) And had written to my mother saying she must take a back seat.

Over twenty-five years: 1924 to 1950. That was then the term of my mother’s exile in Africa. Now I have reached the age to understand that twenty-five years – or thirty – can seem nothing much, I know that for her time had contracted and that unfortunate experience, Africa, had become an irrelevance. But for me, just over thirty, it was the length of my conscious life, and my mother lived in, belonged to, Africa. Her yearnings after London pea-soupers and jolly tennis parties were mere whimsies.

How could she come after me like this? Yet of course she had been bound to. How could she imagine that … But she did. Soon she would toil up those impossible narrow stairs, smiling bravely, walk into my room, move the furniture about, look through my clothes and pronounce their unsuitability, look at the little safe on the wall – no fridge – and say the child was not getting enough to eat.

It was at this point Moidi Jokl entered into my life, an intervention so providential that even now I marvel at it.

Moidi was one of the first refugees from communism in London, then still full of refugees from the war, all surviving as they could. She had been Viennese, a communist, a friend of the men who after the war came back from the Soviet Union or wherever else they had been existing, biding their time, to become the government of East Germany. She went to East Germany because she had been their close friend. Then she had been thrown out, because she was Jewish, a victim of Stalin’s rage against the Jews, referred to men as the ‘Black Years’. I have never understood why those victims have never been honoured and remembered by Jews. Everything has been swallowed up by the Holocaust – but all over the Soviet Union, and in all the communist countries of East Europe, Jews were murdered, tortured, persecuted, imprisoned; it was a deliberate genocide. But for some reason Stalin’s deliberate mass murders are never condemned as Hider’s are, although Stalin’s crimes are much more, both in number and in variety. Bad luck about those poor Jews of the years 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952. No one thinks of them – many thousands, perhaps millions?

Moidi was escorted to that East German frontier by a young policeman in tears: he did not like what he was doing.

Gottfried had by this time visited East Berlin, had found his sister and her husband (the eternal student) working in the Kulturbund, and decided to go back to Germany. He had formally applied to the Party for permission to return home but could get no reply to his letters. Moidi Jokl told him he did not understand the first thing about communism. It all worked on whom you knew – this was later called blat. He should get himself over there, pull strings, and he had a chance of being allowed to stay. Not more than a chance. Anyone from the West was considered a criminal and an enemy, and might easily disappear for ever. Never have I heard such vituperation: Gottfried loathed Moidi. But he did take her advice, went back, pulled strings, and survived.

And then there was Peter. Moidi took a good look at my situation with Peter, shut up with me far too often, for long hours in that tiny flat. She had friends, the Eichners, also Austrians, refugees, who lived near East Grinstead. They had several children and were very poor. They lived in an old house on a couple of acres of rough rocky land and took in children at holiday times, up to twenty sometimes, and they all had a very good time. So Peter began to spend days, or a weekend, or – later – a couple of weeks, with the Eichners. I would put him on a coach at Victoria, and at the other end he became one of a gang of country children. This arrangement could not have been better for him, or for me.

And then, Moidi saw the state I was in because of my mother’s imminent arrival and told me I should go to a friend of hers, Mrs Sussman (Mother Sugar in The Golden Notebook), because if I didn’t get some help, I would not survive. She was right. These days, everyone goes to a therapist, or is a therapist, but then no one did. Not in England, only in America, and even there the phenomenon was in its infancy. And particularly communists did not go ‘into analysis’, for it was ‘reactionary’ by definition, or rather without the need for definition. I was so desperate I went. I went two or three times a week, for about three years. I think it saved me. The process was full of the wildest anomalies or ironies – the communist word ‘contradictions’ seems too mild. First, Mrs Sussman was a Roman Catholic, and Jungian, and while I liked Jung, as all artists do, I had no reason to love Roman Catholics. She was Jewish, and her husband, a dear old man, like a Rembrandt portrait, was a Jewish scholar. But she had converted to Roman Catholicism. This fascinated me, the improbability of it, but she said my wanting to discuss it was merely a sign of my evading real issues. Enough, she said, that Roman Catholicism had deeper and higher levels of understanding, infinitely removed from the crudities of the convent. (And Judaism did not have such higher reaches or peaks? ‘We were talking about your father, I think, my dear. Shall we go on?’) Mrs Sussman specialized in unblocking artists who were blocked, could not write or paint or compose. This is what she saw as her mission in life. But I did not suffer from a ‘block’. She wanted to discuss my work. I did not want to. I did not see the need for it. So she was perpetually frustrated, bringing up the subject, while I deflected her. Mrs Sussman was a cultivated, civilized, wise old woman, who gave me what I needed, which was support. Mostly support against my mother. When the pressures came on, all of them intolerable, because my mother was so pathetic, so lonely, so full of emotional blackmail – quite unconscious, for it was her situation that undermined me – Mrs Sussman simply said, if you don’t stand firm now, it will be the end of you. And the end of Peter too.’

My mother was … but I have forgotten which archetype my mother was. She was one, I know. Mrs Sussman would often bring some exchange to a close: She, he, is such and such an archetype … or is one at this time. I, for example, at various times was Electra, Antigone, Medea. The trouble was, while I was instinctively happy with the idea of archetypes, those majestic eternal figures, rising from literature and myth like stone shapes created by Nature out of rock and mountain, I hated the labels. Unhappy with communism I was unhappiest with its language, with the labelling of everything, and the vindictive or automatic stereotypes, and here were more of them, whether described romantically as ‘archetypes’ or not. I did not see why she minded my criticisms, for she liked the dreams I ‘brought’ her. Psychotherapists are like doctors and nurses who treat patients like children: ‘Just a little spoonful for me.’ ‘Put out your tongue for me.’ When we have a dream, it is ‘for’ the therapist. Often it is: I swear I dreamed dreams to please her, after we had been going along for a while. But at my very first session she had asked for dreams, preferably serial dreams, and she was pleased with my ancient-lizard dream and the dreams I was having about my father, who, too shallowly buried in a forest, would emerge from his grave, or attract wolves who came down from the hills to dig him up. ‘These are typically Jungian dreams,’ she would say gently, flushed with pleasure. ‘Sometimes it can take years to get someone to dream a dream on that level.’ Whereas ‘Jungian’ dreams had been my night landscape for as long as I could remember, I had not had ‘Freudian’ dreams. She said she used Freud when it was appropriate, and that was, I gathered, when the patient was still at a very low level of individuation. She made it clear that she thought I was.*

‘Jungian dreams’ – wonderful, those layers of ancient common experience, but what was the use of that if I had to go to bed with the covers over my head at the news my mother was about to arrive? Here I was. Here I am, Mrs Sussman. Do what you will with me, but for God’s sake, cure me.

I needed support for other reasons.

One of them was my lover. Moidi Jokl suggested that I should go with her one evening to a party, and there I met a man I was destined – so I felt then – to live with, and to have and to hold and be happy with.

Yes, he had a name. But as always, there is the question of children and grandchildren. Since Under My Skin came out, I have met not a few grandchildren, children, of my old mates from those far-off times and learned that the views of contemporaries about each other need not share much with the views of their children. Whole areas of a parent’s, let alone a grandparent’s, life can be unknown to them. And why not? Children do not own their parents’ lives, though they – and I too – jealously pore over them as if they hold the key to their own.

I say to a charming young man who has come to lunch to discuss his father, ‘When James was working on the mines on the Rand –’

‘Oh, I’m sure he never did that,’ comes the confident reply.

To another: ‘You didn’t know your father was a great lover of women?’ A faindy derisive smile, meaning: What, that old stick? So then of course you shut up; after all, it has nothing to do with him.

I will call this man Jack. He was a Czech. He had worked as a doctor with our armies throughout the war. He was – what else? – a communist.

He fell in love with me, jealously, hungrily, even angrily – with that particular degree of anger that means a man is in conflict. I did not at once fall in love with him. At the start, what I loved was his loving me so much: a nice change after Gottfried. The way I saw this – felt this – was that now I was ready for the right man: my ‘mistakes’ were over, and I was settled in London, where I intended to stay. All my experiences had programmed me for domesticity. I might now tell myself – and quite rightly – that I had never been ‘really’ married to Frank Wisdom, but for four years we had a conventional marriage. Gottfried and I had hardly been well matched, but we had lived conventionally enough. The law and society saw me as a woman who had had two marriages and two divorces. I felt that these marriages did not count. I had been too young, too immature. The fact that the bouncy, affectionate, almost casual relationship I had had with Frank was hardly unusual – particularly in those war years, when people married far too easily – did not mean I did not aspire to better. With Gottfried it had been a political marriage. I would not have married Gottfried if the internment camp was not still a threat. Then, people were always marrying to give someone a name, a passport, a place; in London there were organizations for precisely this – to rescue threatened people from Europe. But now, in these luckier times, people have forgotten that such marriages were hardly uncommon. No, my real emotional life was all before me. And I had all the talents needed for intimacy. I was born to live companionably – and passionately – with the right man, and here he was.

Jack had been one of thirteen children, the youngest, of a very poor family in Czechoslovakia. He had had to walk miles to school and back – just like Africans now in many parts of Africa. They scarcely had enough to eat or to cover themselves with. This was a common enough story, then, in Europe – and in some parts of Britain too: people don’t want to remember the frightful poverty in Britain in the twenties and thirties. Jack had become a communist in his early teens, like all his schoolfellows. He was a real communist, for whom the Party was a home, a family, the future, his deepest and sanest self. He wasn’t at all like me – who had had choices. When I met him, his closest friends in Czechoslovakia, the friends of his youth, the top leadership of the Czech Communist Party, had just been made to stand in the eyes of the world as traitors to communism, and then eleven of them were hanged, Stalin the invisible stage manager. For Jack it had been as if the foundations of the world had collapsed. It was impossible for these old friends to have been traitors, and he did not believe it. On the other hand, it was impossible for the Party to have made a mistake. He had nightmares, he wept in his sleep. Like Gottfried Lessing. Again I shared a bed with a man who woke from nightmares.

That was the second cataclysmic event of his life. His entire family – mother, father, and all his siblings, except one sister who had escaped to America – had died in the gas chambers.

This story is a terrible one. It was terrible then, but taken in the context of that time, not worse than many others. In 1950 in London, everybody I met had come out of the army from battlefields in Burma, Europe, Italy, Yugoslavia, had been present when the concentration camps were opened, had fought in the Spanish war or was a refugee and had survived horrors. With my background, the Trenches and the nastiness of the First World War dinned into me day and night through my childhood. Jack’s story was felt by me as a continuation: Well, what can you expect?

We understood each other well. We had everything in common. Now I assess the situation in a way I would then have found ‘cold’. I look at a couple and I think. Are they suited emotionally … physically … mentally? Jack and I were suited in all three ways, but perhaps most emotionally, sharing a natural disposition towards the grimmest understanding of life and events that in its less severe manifestations is called irony. It was our situations, not our natures, that were incompatible. I was ready to settle down for ever with this man. He had just come back from the war, to find his wife, whom he had married long years before, a stranger, and children whom he hardly knew.

It is a commonplace among psychiatrists that a young woman who has been close to death, has cut her wrists too often, or has been threatened by parents, must buy clothes, be obsessed with clothes and with the ordering of her appearance, puzzling observers with what seems like a senseless profligacy. It is life she is keeping in order.

And a man who has been running a step ahead of death for years – if Jack had stayed in Czechoslovakia it is likely he would have been hanged as a traitor, together with his good friends, if he hadn’t already perished in the gas chambers – such a man will be forced by a hundred powerful needs to sleep with women, have women, assert life, make life, move on.

In no way can I – or could I then – accuse Jack of letting me down, for he never promised anything. On the contrary, short of actually saying, ‘I am sleeping with other women; I have no intention of marrying you,’ he said it all. Often joking. But I wasn’t listening. What I felt was: When we get on so wonderfully in every possible way, then it isn’t sensible for him to go away from me. I wasn’t able to think at all; the emotional realities were too powerful. I think this is quite common with women. ‘Really, this man is talking nonsense, he doesn’t know what is right for him. And besides, he says himself his marriage is no marriage at all. And obviously it can’t be, when he is here most nights.’ How easy to be intelligent now, how impossible then.

If I needed support against my mother, soon I needed it because of Jack too. He was a psychiatrist at the Maudsley Hospital. He had wanted to be a neurologist, but when he started being a doctor in Britain, neurology was fashionable and ‘a member of a distant country of which we know nothing’ could not compete with so many British doctors, crowding to get in. So he went into psychiatry, then unfashionable. But soon it became chic, even more so than neurology. He was a far from uncritical practitioner. He was no fan of Freud, and this was not only because as a communist – or even an ex-communist – he was bound to despise Freud. He said Freud was unscientific, and this at a time when to attack Freud was like attacking Stalin – or God. One of my liveliest memories is of how he took me to Oxford to listen to Hans Eysenck lecture to an audience composed almost entirely of doctors from the Maudsley, all of them Freudians, about the unscientific nature of psychoanalysis. There he was, this large, bouncing young man, with his thick German accent, telling a roomful of the angriest people I remember that their idol had faults. (He has not lost his capacity to annoy: when I told a couple of young psychiatrists this tale, thinking it might amuse them – in 1994 – their cold response was: ‘He always was unsound.’) Jack admired him. He knew psychoanalysis had feet of clay. This scepticism included Mrs Sussman: And if Freud was unscientific, what could be said of Jung? But I didn’t go to Mrs Sussman for ideology, I said. And anyway, she used a pragmatic mix of Freud, Jung, Klein, and anything else that might come in appropriately. He did not find this persuasive; he said that all artists like Jung, but this had nothing to do with science: why not just go off and listen to lectures on Greek mythology? It would do just as well. He was unimpressed by my ‘Jungian’ dreams. And even less when I began dreaming ‘Freudian’ dreams. And I was uneasy myself. I was dreaming dreams to order. No one need persuade me of the influence a therapist has on a confused, frightened suppliant for enlightenment. One needs to please that mentor, half mother, half father, the possessor of all knowledge, sitting so powerfully there in that chair. ‘And now, my dear, what do you have to tell me today?’

Some things I wouldn’t dare tell Jack. For instance, about that day when she remarked, after nothing had been said for a few minutes, ‘I am sure you do know that we are communicating even when we are not saying anything.’ This remark, at that time, was simply preposterous. As far as she was concerned, I was a communist and therefore bound to dismiss any thoughts of that kind as ‘mystical nonsense’. She was not talking about body language (that phrase, and the skills of interpreting people’s postures, gestures, and so forth, came much later). She was talking about an interchange between minds. As soon as she said it, I thought, Well, yes… accepting this heretical idea as if it was my birthright. But to say this to Jack … For though he might have been, now, painfully – and for him it had to be painful – critical of communism, he was a Marxist, and ‘mystical’ ideas were simply inadmissible.

Jack attacked me for going to Mrs Sussman at all. He said I was a big girl now and I should simply tell my mother to go off and live her own life. She was healthy, wasn’t she? She was strong? She had enough money to live on?

My mother’s situation was causing me anguish. She was living pitifully in a nasty little suburb with George Laws, a distant cousin of my father’s. He was old, he was an invalid, and they could have nothing in common. She kept up a steady pressure to live with me. There was nowhere else for her. She found her brother’s family – he had died – as unlikeable as she always had. She actually had very little money. Common sense, as she kept saying, would have us sharing a flat and expenses, and besides, I needed help with Peter. Her sole reason for existence, she said, was to help me with Peter. And she took Peter for weekends, sometimes, and on trips. From one, to the Isle of Wight, he returned baptized. She informed me that this had been her duty. I did not even argue. There was never any point. And of course it was very good, for me, when I could go off with Jack for three days. At these times she moved into the Church Street flat, where the stairs were almost beyond her. Joan did not mind my mother; she simply said. But she’s a typical middle-class matron, that’s all. Just as I didn’t mind her mother, with whom she found it difficult to get on. I could listen to her self-pitying, wailing tales of her life dispassionately – this was social history, hard times brought off the page into a tale of a beautiful Jewish girl from the poor East End of London surviving among artists and writers.

Jack said I should simply put my foot down with my mother, once and for all.

Joan was also involved – a good noncommittal word – with psychotherapy. Various unsuccessful attempts had ended in her returning from a session to say that no man who had such appalling taste in art and whose house smelled of overcooked cabbage could possibly know anything about the human soul. That was good for a laugh or two, as so many painful things are.

Joan saw her main problem as the inability to focus her talents. She had many. She drew well – like Kathe Kollwitz, as people told her: this was before Kollwitz had been accepted by the artistic establishment. She danced well. She had acted professionally. She wrote well. Perhaps she had too many talents. But whatever the reason, she could not narrow herself into any one channel of accomplishment. And here I was, in her house, getting good reviews, with three books out. She was critical of Jack, and of me because of how I brought up Peter. I was too lax and laissez-faire, and treated him like a grown-up. It was not enough to read to him and tell him stories; he needed … well, what? I thought she criticised me because of dissatisfaction over her son, for no woman can bring up a son without a full-time father around and not feel at a disadvantage. And then I was such a colonial, and graceless, and perhaps she found that hardest of all. Small things are the most abrasive. An incident: I have invited people to Sunday lunch, and among the foods I prepare are Scotch eggs, this being a staple of buffet food in Southern Africa. Joan stands looking at them, dismayed. ‘But why,’ she demands, ‘when there’s a perfectly good delicatessen down the street?’ She criticised me – or so it felt – for everything. Yet this criticism of others was the obverse of her wonderful kindness and charity, the two things in harness. And it was nothing beside her criticism of herself, for she continued to denigrate herself in everything.

To withstand the pressure of this continual disapproval, I got more defensive and more cool. Yes, this was a repetition of my situation with my mother, and of course it came up in talk with Mrs Sussman, who was hearing accounts of the same incidents from both of us, Box and Cox, and supported us both. Not an easy thing. One afternoon Joan came rushing up the stairs to accuse me of having pushed her over the cliff.

‘What?’

‘I was dreaming you pushed me over the cliff.’

When I told Mrs Sussman, she said, ‘Then you did push her over the cliff.’

Joan was unable to see that I found her overpowering because I admired her. She was everything in the way of chic, self-confidence, and general worldly experience that I was not. And years later, when I told her that this was how I had seen her, she was incredulous.

Jack saw her as a rival – or so it seemed to me – for if she criticised him, then he criticised her. ‘Why don’t you get your own place? Why do you need a mother figure?’ He did not see that being in Joan’s house protected me from my mother, or that it was perfect for Peter.

Jack thought I was too protective of Peter. He found it difficult to get on with his son and said frankly that he was not going to be a father to Peter.

This was perhaps the worst thing about this time. I knew how Peter yearned for a father, and I watched this little boy, so open and affectionate with everyone, run to Jack and put up his arms – but he was rebuffed, his arms gently replaced by his sides, while Jack asked him grown-up questions, so that he had to return sober, careful replies, while he searched Jack’s face with wide, strained, anxious eyes. He had never experienced anything like this, from anyone.

The difficulties between Joan and me were no more than were inevitable, with two females, both used to their independence, living in the same house. We got on pretty well. We sat often over her kitchen table, gossiping: people, men, the world, the comrades – this last increasingly critical. In fact, gossiping with Joan over the kitchen table is one of my pleasantest memories. We both cooked well; gentle competition went on over the meals we prepared. The talk was of the kind I later used in The Golden Notebook.

A scene: Joan said she wanted me to see something. ‘I’m not going to tell you; just come.’ In a little house in a little street two minutes’ walk away, we found ourselves in a little room crammed with valuable furniture and pictures and, too, people. Four people filled it, and Joan stood at the doorway, me just behind, and waved to a languorous woman lying on a chaise longue, dressed in a frothy peignoir. A man bent over her, offering champagne: he was a former husband. Another, a current lover, fondled her feet. A very young man, flushed, excited, adoring, was waiting his chance. No room for us, so we said goodbye, and she called, ‘Do come again, darlings, any time. I get so down all by myself here.’ She was afflicted by a mysterious fatigue that kept her supine. It appeared that she was kept by two former husbands and the current lover. ‘Now, you tell me,’ says Joan, laughing, as we walk home. ‘What are we doing wrong? And she isn’t even all that pretty.’ We returned, worrying, to our overburdened lives.

There we were, two or three times a week, discussing our own behaviour, and each other’s, with Mrs Sussman, but now all that rummaging about among the roots of our motives, then so painful and difficult, seems less important than, ‘I’ve just bought some croissants. Want to join me?’ Or, ‘Have you heard the news – it’s awful. Want a chat?’ What I liked best was hearing her talk about the artists and writers she knew because of her father and of working in the Party. I used to be impressed by her worldly wisdom. For instance, about David Bomberg, who had painted her father; he was then ignored by the artistic establishment: ‘Oh, don’t worry, they’re always like this, but they’ll see the error of their ways when he’s dead.’ Quite calm, she was, whereas I went in for indignation. And David Bomberg lived in poverty all his life, unrecognized, and then he died and it happened as she said. Or she would come from a party and say that Augustus John was there, and she’d told the young girls, ‘Better watch out, and don’t let him talk you into sitting for him,’ for by then Augustus John had become a figure of fun. Or she had been in the pub used by Louis MacNeice and George Barker, near the BBC, and she had been in the BBC persuading Reggie Smith, always generous to young writers, to take a look at this or that manuscript. She was one of the organizers of the Soho Square Fair in 1954, and they must have had a good time of it. I’d hear her loud jolly laugh and her voice up the stairs: ‘You’d never believe what’s happened. I’ll tell you tomorrow.’

It was Joan who persuaded me to perform my ‘revolutionary duty’ in various ways. I organized a petition for the Rosenbergs, condemned to die in the electric chair for spying. As usual I was in a thoroughly false position. Everyone in the Communist Party believed, or said they did, that the Rosenbergs were innocent. I thought they were guilty, though I had no idea they were as important as spies as it turned out. Someone had told me this story: A woman living in New York, a communist, had got herself a job on Time magazine, then an object of vituperative hatred by communists everywhere because it ‘told lies’ about the Soviet Union. A Party official, met casually, said she should keep her ears and eyes open and report to the Party about the goings-on inside Time. She agreed, quite casually. Then, suddenly, there was spy fever. It occurred to her that she could be described as a spy. At first she told herself, Nonsense, surely it can’t be spying to tell a legal political party, in a democratic country, what is going on inside a newspaper. But the papers instructed her otherwise, and in a panic she left her job. In that paranoid atmosphere there could be no innocent communists. I thought the Rosenbergs had probably said, Oh yes, of course, we’ll tell you if there’s anything interesting going on.

Not only did I think they were guilty, but that the letters they were writing out of prison were mawkish, and obviously written as propaganda to appear in newspapers. Yet the comrades thought they were deeply moving, and these were people who, in any other context but a political one, would have had the discrimination to know they were false and hypocritical.

An important, not to say basic, point is illustrated here. Here we were, committed to every kind of murder and mayhem by definition: you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs. Yet at any suggestion that dirty work was going on, most communists reacted with indignation. Of course So-and-so wasn’t really a spy; of course the Party did not take gold from Moscow; of course this or that wasn’t a cover-up. The Party represented the purest of humankind’s hopes for the future – our hopes – and could not be anything other than pure.

My attitude to the Rosenbergs was simple. They had small children and should not be executed, even if guilty. The letters I got back from writers and intellectuals mostly said that they did not see why they should sign a petition for the Rosenbergs when the Party refused to criticise the Soviet Union for its crimes.

I did not see the relevance: it was morally wrong to execute Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. I was again in the position of public and embattled communist; I was getting hate letters and anonymous telephone calls. In times of violent political emotion, issues like the Rosenbergs attract so much anger and hate that soon it is hard to remember that under all this noise and propaganda is a simple choice of right and wrong. And after all these years, there is still something inexplicable about this case. Soon there would be many spies exposed in Britain and America, some of them betraying their country for money, some sending dozens of fellow citizens to their deaths, yet not one of them was hanged or sent to the chair. The Rosenbergs’ crime was much less, and they were parents with young children. Some people think it was because they were Jewish. Others – I among them – wonder if their condemners got secret pleasure from the idea of a young, plump woman being ‘fried’. There are issues that are very much more than the sum of their parts, and this was one.

Another ‘duty’ I undertook at Joan’s behest was the Sheffield Peace Conference. My job was to go around to houses and hand out leaflets, extolling this festival. I was met at every door with a sullen, cold rejection. The newspapers were saying that the festival was Soviet inspired and financed – and of course it was, but we indignantly denied it and believed our denials. It was a truly nasty experience, perhaps the worst of my revolutionary duties. It was cold, it was grey, no one could describe Sheffield as beautiful, and I had not yet experienced the full blast of British citizens’ hostility to anything communist.*

With Jack I went on two trips to Paris. The little story ‘Wine’ sums up one. We sat in a cafe on the Boulevard St-Germain and watched mobs of students surge shouting past, overturning cars. What was their grievance? Overturning cars is a peculiarly French means of self-expression: Jack had seen the same thing before the war, and I saw it again on a much later visit.

Another incident, the same trip, another cafe: We are sitting on the pavement, drinking coffee. Towards us comes, or sweeps, a wonderfully dressed woman, with her little dog. She is a poule, luxurious, perfect, and no, you don’t see prostitutes looking like that in Paris now. Jack is watching her, full of regret and admiration. He says to me in a low voice, ‘God, just look, only the French …’ Coming level with us, she pauses long enough to stare with contempt at Jack and say, ‘Vous êtes très mal élevé, monsieur.’ You are very ill-bred, sir. Or, You are a boor. And she sweeps past.

‘But why present yourself like that if you don’t want to be noticed?’ says Jack. (This is surely a question of much wider relevance.) ‘But if one did have the money for a woman like that, would one dare to touch her? I might upset her hairdo.’

On the second visit, we were in a dark cellar-like room, where a reverent audience, all French, watched a pale woman in a long black dress with a high collar, unmade up except for tragic black-rimmed eyes, sing ‘Je ne regrette rien’ and other songs that now seem the essence of that time. (This style would shortly become the fashion.) What it sounded like was a defiant lament for the war, for the Occupation. On the streets of Paris then you kept coming on a pile of wreaths, or bunches of flowers on a pavement, under bullet holes, and a notice: Such and such young men were shot here by the Germans. And you stopped, too, in an anguish of fellow feeling, not unpoisoned by a pleasurable relish in the drama of it.

And we went to the theatre, to see Brecht’s company, The Berliner Ensemble, put on Mother Courage. No German company had yet dared to put a play on in Paris. Jack said he thought there would be a riot: Germans so soon; surely that was too much of a risk; but we should go. It would be a historical occasion. After all, it was Brecht. The first night: the theatre was packed, people standing, and outside there were too many policemen. Things did not go smoothly. There had been time only for an inadequate rehearsal. That story of war, so apt for the time and place, unfolded in silence. No one stirred. There was a hitch with the props, and still no one moved. No interval, because everything was dragging on so late. Soon the silence became unbearable: Did it mean they hated it? that the audience would go rioting onto the stage for some sort of reprisal or revenge? When the play ended, with the words ‘Take me with you, take me with you,’ and the disreputable old woman, stripped of everything, again tried to follow the army, there was something like a groan from the French. Silence, silence, no one moved, it went on – and then the audience were on their feet, roaring, shouting, applauding, weeping, embracing, and the actors stood on the stage and wept. It all went on for a good twenty minutes. About halfway through, that demonstration stopped being spontaneous and became Europe conscious of itself, defeated and disgraced Germany crying out to Europe, Take me with you, take me with you.

I’ve never had an experience like that in the theatre, and it taught me once and for all that a play can have its perfect occasion, as if it had been written for that performance alone. I’ve seen other productions of Mother Courage since.

Later the Canadian writer Ted Allan told me that when Brecht was a refugee in California, he was baby-sitting for the Allans. He asked Ted to read the just completed Mother Courage, and Ted did, and told Brecht it was promising but needed this and that. Helene Weigel was indignant. ‘It’s a masterpiece,’ she said. Ted used to tell this story against himself, polishing it, as befits a real storyteller. His criticisms of Brecht became more crass, a parody of Hollywood film-makers. ‘Get rid of that old bitch. You’ve got to sex it up. You need a babe there. I’ve got it – how about a nun. No, a novice, real young. Let’s see … Lana Turner … Vivien Leigh …’

One trip with Jack was to Spain for a month. This was our longest yet. My mother stayed with Peter for part of it, Joan had him for a week, he was with the Eichners for the rest. We had very little money. Jack was not a senior doctor, and he had a family to keep. Could we each manage twenty-five pounds? The trip, with expenses for the car, travel, cost us fifty pounds. We ate bread and sausage and green peppers and tomatoes and grapes. I can’t smell green peppers that still have the heat of the sun in them without being encompassed by memories of that trip. As you crossed the frontier from France, it was to go back into the nineteenth century. This was before tourism started. As we drove into the towns, like Salamanca, Avila, Burgos, crowds pressed forward to see the foreigners. Ragged boys competed to guard the car: sixpence for a day or a night. When we did actually eat in a cheap restaurant, hungry children pressed their faces against the glass. For Jack, we were driving through ghostly memories of the Spanish Civil War: he had lived, in his imagination, through every stage of every battle. He had suffered because of the betrayal of the elected Spanish government by Britain and France: for him and people like him, that was when World War II had begun. Now he was suffering over the hungry children, remembering his own childhood. He was angry to see the streets full of black-robed fat priests and the police in their black uniforms, with their guns. Spain was so poor then it broke your heart, just like Ireland.

And yet … We slept wrapped in blankets out in a field, in the open because of the stars. One morning, already hot, though the sun was just rising, we sat up in our blankets to see two tall dark men on tall black horses, each wearing a red blanket like a serape, riding past us and away across the fields, the hot blue sky behind them. They lifted their hands in greeting, unsmiling.

We ate our bread and olives and drank dark-red wine under olive trees or waited out the extreme heat of midday in some little church, where I had to be sure my arms were covered, and my head too.

We went to a bullfight, where Jack wept because of the six sacrificed bulls. He was muttering, Kill him, kill him, to the bulls.

In Madrid beggar women sat on the pavements with their feet in the gutters, and we gave them our cakes and ordered more for them.

We felt in the Alhambra that this was our place – the Alhambra affects people strongly: they hate it or adore it.

We quarrelled violently, and often. It is my belief and my experience that energetic and frequent sex breeds sudden storms of antagonism. Tolstoy wrote about this. So did D. H. Lawrence. Why should this be? We made love when we stopped the car in open and empty country, in dry ditches, in forests, in vineyards, in olive groves. And quarrelled. He was jealous. This was absurd, because I loved him. In a town in Murcia, where it was so hot we simply stopped for a whole day to sit in a cafe, in the shade if not the cool, he was convinced I was making eyes at a handsome Spaniard. This quarrel was so terrible that we went to a hotel for the night, because Jack, the doctor, said that our diet and lack of sleep was getting to us.

We drove from Gibraltar up the costas, where there were no hotels, not one, only a few fishermen at Nerja, who cooked us fish on the beach. We slept on the sand, looking at the stars, listening to the waves. Nothing was built between Gibraltar and Barcelona then; except for the towns, there were only empty, long, wonderful beaches, which in a year or so would become hotel-loaded playgrounds. Near Valencia, a sign said, ‘Do Not Bathe Here – It Is Dangerous,’ but I went into the tall enticing waves, and one of them picked me up and smashed me onto the undersea sand, and I crawled out, my ears full of sand and grit. Jack took me to the local hospital, where the two doctors communicated in Latin, proving that it is a far from dead language.

In high, windy Avila there were acres of wonderful brown jars and pots, standing on dry reeds. I bought the most beautiful jar I have ever owned, for a few pence.

What struck me most then, and surprises me even now, is the contrast between the wild, savage, empty beauty of Spain and the stuffy stolidity of even the cheap hotels we could afford, between the poverty we saw everywhere and the churches loaded with gold and jewels, as if all the wealth of the peninsula had come to rest in them.

We visited Germany, three times. The first was when I wanted to find Gottfried. Peter had gone the year before for a summer to visit his father. I had told Gottfried he must not have him do this unless he was sure he could keep it up. As usual he was contemptuous of my political acumen: of course he would be able to invite Peter whenever he liked. I said I wasn’t so sure; besides, Moidi Jokl said he was wrong. I turned out to be right. Germans who had spent the war abroad were suspect, and many vanished into Stalin’s camps. I was angry, partly for the ignoble reason that I had been insulted and patronized by Gottfried for years about politics but in fact had been more often right, and he wrong. I was angry because of Peter, who had had a wonderfully kind father who had apparently dropped him.

Now I understand what happened. It was indeed a question of life and death. What I blame him for is for not smuggling out a little letter saying, I cannot afford to keep contact with the West; I might be killed for it. It would have been easy: there was a good deal of to-ing and fro-ing. Instead people would come back from some official trip to East Germany and say, I saw your handsome husband. He is a very important man. He sends you his love. ‘He is not my husband,’ I would say, ‘and it is Peter who needs his love.’ I hated East Berlin. For me it was like a distillation of everything bad about communism, but some comrades admired it. For years, right up to the time of the collapse of communism, they were saying, ‘East Germany has got it right. It is economically in advance of any other communist country. What a pity the revolution didn’t start in Germany.’