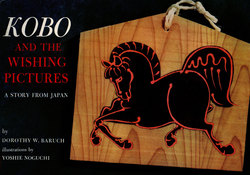

Читать книгу Kobo and the Wishing Pictures - Dorothy Baruch - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLOOKING FORWARD TO WISHING DAY

Kobo slipped out of his shoes. He placed them in Japanese fashion on the stone step outside his house. Then he stood there for a moment in the warm sunshine and wiggled his toes. This was the first day that they did not tingle with the cold.

"Hai!" Kobo gulped in excitement. "Spring is in the air. I can smell it. And I can feel it, too. That means Wishing Day will soon be here." Kobo smiled to himself.

Springtime meant wishing time: to pray for a good rice crop, to wish also for the one thing that one wanted most for oneself. Standing there a little longer and sniffing the sweet, fresh air, Kobo wondered: "What shall I wish?"

It was something that he would have to think about.

Inside, Kobo found his mother with Little Brother on her back. She, too, had felt the warmth of spring in the air, and she was changing the winter picture on the wall to the springtime picture. Kobo's younger sister Tako was arranging three plum branches dotted with their first opening buds.

At the other side of the room, seated on the floor and wearing his brown kimono, was Kobo's father. He was an artist. His paints were laid out before him in splashes of brightness. He had just finished washing his brushes. They stood like little sprigs of bamboo in the pottery cups in which he kept them.

This was his busiest time of the year. For with spring in the air, everyone would remember that in four days the Wishing Festival would be here. The people would then go to the shrine of the Rice Goddess, and they would take with them paintings of the things they wished for. They would pray to the Rice Goddess to grant their wishes. And they would hang their wishing pictures on the wall of the shrine as an offering and a reminder to the goddess not to forget them.

"This year," Kobo thought, "I shall hang a picture of my own." He would ask his father to paint it for him. But first Kobo had an important decision to make. There were so many wishes crowding in his mind. Which one should he really wish?

Just then, Father looked up for a moment. "Come, Elder Son," he said. "Come and help me."

Quietly Kobo went over to where his father was working. On the floor were the small wooden plaques on which he painted the ema: the wishing pictures. With careful fingers Father was checking to see that the wood was smooth. Just as carefully, Kobo arranged the plaques in neat little piles. "Ichi, ni, san, shi, go," Kobo counted, whispering so as not to disturb Father's thinking. One, two, three, four, five little piles.

"On one of these," thought Kobo, "Father will paint my picture, when I decide what my best wish is."

But what should he wish? It was strange that he couldn't make up his mind. Yet not so strange, really. Because this was no ordinary wish. It had to be the very best, the very greatest thing that he could wish for. Perhaps if he listened carefully to what his father's customers wanted in their ema wishing pictures, it would help him decide on his own best wish.