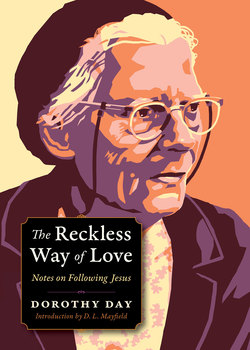

Читать книгу The Reckless Way of Love - Dorothy Day - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTo the Reader

DOROTHY DAY’S passion for peace and social justice and her dedication to serving the poor are legendary, and her fame continues to grow. Despite her own protests, admirers have petitioned the Vatican to make her a saint. She was one of four people Pope Francis named as truly great Americans. Yet combing through Dorothy’s books and articles and her private letters and journals, one discovers an underappreciated dimension of her life. Where did a conflicted young woman find the inner strength to answer the clear call she heard from God? And how did she go on to live such an active, selfless life for so many decades without losing heart or burning out? Unlike other collections, this little volume brings together Dorothy’s thoughts on the life of discipleship, the reckless way of love to which Jesus calls his followers. Dorothy’s dogged struggle to hold on to faith, her love for those hardest to love, and her rootedness in prayer can guide and encourage each of us in our own attempts to follow more faithfully in the way of Jesus.

The story of Dorothy Day’s life has been told well elsewhere, so the briefest biographical sketch here will suffice. There’s certainly no better place to start than her own books, The Long Loneliness and Loaves and Fishes.

Born in Brooklyn in 1897, Dorothy’s early years were marked by dramatic twists and turns. There was journalism school, and then a taste of the bohemian Twenties, first in New York City, then Italy, then Hollywood, and finally Staten Island. These were whirlwind years, and left her reeling from a broken marriage, an abortion, and a series of unhappy relationships.

But there was also an unforgettable night in a Greenwich Village bar where her friend, the playwright Eugene O’Neill, recited “The Hound of Heaven” for her – a poem whose obscure but deep message, she later said, eventually brought about her conversion.

In 1926 Dorothy had a baby daughter, Tamar – an event that profoundly changed her. When leftist friends mocked her new interest in the Gospels, Dorothy told them that Jesus promised the new society of justice they were all looking for. If Christians tended to be hypocrites, that was not Jesus’ fault. She was determined to give him a try.

In the years that followed, Dorothy did more than try. Shaken by the hopelessness of the unemployed millions during the Depression years, she dropped all ambitions of becoming a famous writer and spent the rest of her life serving the poor (in whose face she saw Jesus), spreading her views of nonviolence (she was imprisoned many times for acts of civil disobedience), and passionately reminding readers through her books and newspaper articles that Christ demanded more than tithes, hats, and flowers on Sunday.

As far as Dorothy could tell, he demanded the readiness to wash vegetables, cut bread, and clean up after hundreds of noisy, often ungrateful guests, day after day, year after year. This she did gladly at the New York Catholic Worker – a communal hospitality house for the unemployed and homeless that she founded with Peter Maurin in 1933.

When Dorothy Day died in 1980 in the cramped Lower East Side room she called home, she owned nothing but a creaking bed, a writing desk, an overflowing bookshelf, a teapot, and a radio. Yet her witness lives on. On a practical level, the work continues today in more than a hundred Catholic Worker houses across the United States and beyond. And as you will find in these pages, we are left with the enduring challenge of her no-nonsense attitude to faith: “The mystery of the poor is this: that they are Jesus, and whatever you do for them you do to him.”