Читать книгу Vertical Horizons - Douglas M. Grant - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

The Second Decade: 1950–60

1950

With more work on the Palisade dam project, a second Alcan survey and construction of a test transmission line, the company’s outlook for 1950 was positive. However, the first job of the year was a small one in the Bridge River–Lillooet area, delivering supplies to the Bralorne Mine and carrying out a power-line patrol after a heavy snowfall blocked the railroads and roads leading to the mine.

Although the company’s helicopters had been busy moving from one job to the next in 1949, OAS had still not broken even, and as most financial institutions felt helicopter ventures were far too risky, it was difficult to obtain further financing. The situation was eased somewhat when a bank extended a line of credit and Douglas Dewar contributed a modest personal loan.

Over the course of the summer of 1950, the financial situation improved as funds from the various contracts came in, though it continued to be a hand-to-mouth existence. There was simply no money to hire additional staff or buy another helicopter. Cash flow for the fixed-wing side of the company was barely covering expenses, and after a devastating accident that killed a student pilot and destroyed one of the company’s Cessnas, the directors agreed to sell that part of the operation for any reasonable offer.

At one of the directors’ meetings Carl and Alf’s optimism clashed head-on with the financial team led by Douglas Dewar. Carl pointed out that the company needed financing for more equipment or the competition would move in and take the work. While Dewar respected Carl’s skills as a pilot, he felt that he did not have business sense. In the end they reached a compromise: even though Carl did not get his expanded fleet, he did get funding to hire more operational staff, with a priority on engineers to assist Alf who had been stretched to his limits the previous year. As a result, by the end of the year, CF-FZX and CF-FZN each had a dedicated aircraft engineer.

The company had no problem attracting aircraft engineers as they all wanted to work on the “egg beater.” The first to be hired was John “Jock” Fraser Graham who had trained with the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and worked on flying boats for Coastal Command. He’d had a colourful career as a flight engineer, including time spent as a prisoner of war just outside Casablanca. Two Canadian pilots had encouraged him to emigrate to Canada, and on arrival he had joined Queen Charlotte Airlines (QCA), which had a diverse fleet of Norsemen, Stranraers, Cansos, Ansons and DC3s. He had hoped to become a commercial pilot and was trying to build up his hours in anticipation of a position flying float planes, but in the summer of 1949 he had encountered his first helicopter (CF-FZN) after OAS rented space in a corner of the QCA hangar at Vancouver Airport. He was impressed with Alf and Carl’s ability to handle problems without getting excited: the first time they met, Carl was running the machine after a transmission change when a swarm of bees settled on the tail boom. As the bees were not bothering the run-up, Carl continued until he had finished the checks, then shut the machine down and went to find a beekeeper. Toward the end of that year Carl and Alf told him they would hire him effective January 1, 1950. His training was on the job, rebuilding CF-FZN, but he was happy to give up his secure airline job to become a field engineer. He told an interviewer:

You felt like you were really pioneering because [the helicopters] were open cockpit Bell 47B-3s. You felt you were right back with Wilbur and Orville Wright and you had a sense of flying. You had to be dressed for it. In the winter you had to wear everything you had.10

OAS also needed a pilot to replace Paul Ostrander. Carl had developed a very demanding training plan that incorporated his own experiences and observations, but he looked for pilots who already had a well-developed air sense, experience in mountain flying and the ability to anticipate trouble and take appropriate action. OAS pilots were expected to fly in rugged mountains, land on isolated peaks or tiny platforms and tolerate primitive living conditions. They also needed to command respect and appreciate the customer’s point of view.

Carl met Bill McLeod, an ex-RCAF flying instructor, in a Vancouver airport coffee shop. During the war Bill had applied for aircrew, but when he was initially turned down, he had spent some time as an engineer before being finally accepted for pilot training. Later he had become an elementary flying instructor, and when he was posted to Abbotsford, Carl had been his commanding officer. After the war Bill got a job flying QCA’s Stranraer flying boats and Norseman float planes in difficult weather through the maze of inlets and islands along the West Coast of BC. When Carl asked him if he would like to fly helicopters, he replied that he had never even seen a helicopter, so Carl invited him to join him on a little job hanging a hook attached to a long rope on a smokestack at one of the lumber mills on the Fraser River. This set-up would allow steeplejacks to climb the stack then pull up the equipment they needed to work on it. McLeod recalled:

So I climbed into this stupid machine—at that time I figured it was a stupid machine—it was the open-cockpit Bell 47B-3 with the four wheels. They had had a hook manufactured—a homemade thing with a sort of a loop on the bottom and a long arm welded to it so I could reach out and clip it over the edge of the steel chimney. The rope went through the loop and I had the rest of it, a big coil of heavy rope, in my lap.

So we took off and chugged off along the Fraser. There was a nice brisk wind blowing from the west about 25 miles an hour [40 km/h], which gave us a bit of added lift. Carl steamed up alongside this smokestack, and I found I couldn’t handle the pole sitting down. I had to put the rope on the floor, undo my seat belt, climb half out of the machine and put one foot on the wheel leg to hold the pole properly. Anyway, I got the hook on, picked up the rope and threw it down and got back into my seat. Then I realized the long handle of the hook was against my stomach, and if Carl started to move forward I was going to end up with a bad stomach ache. So I got back out again, held onto the door frame, put my foot against the smokestack and gave a good shove. The machine moved away and the handle dropped out. I sat down again and gave Carl the thumbs up and away we went. By the time we got back to the airport, I was thinking: “Anything you can do that with, I’ve got to learn to fly.”11

Carl trained Bill McLeod over the winter, and by the time he took on his first job with OAS in the spring, he had put in a total of 60 hours. Bill recalled the encouragement he received at the start of his first helicopter operation:

When the machine was loaded up and I was ready to leave for Kispiox, [BC], Carl came out and shook hands with me, and he said, “Well, Bill, remember one thing—if you get through the season without breaking a helicopter, you’ll be the first man who’s ever managed to do so.” With those happy words ringing in my ear, I climbed in the machine and took off. As it turned out, I did manage to get through the first season without breaking a helicopter, but I sure scared the hell out of myself a few times.

You see, the truth was you had to learn a whole new ball game. Remember that in an airplane you’re trained right from day one to approach a landing and to take off into wind. If you persist in this in a helicopter in mountain terrain, you’re dead—you’re going to kill yourself; it’s just that simple. Because it means that if you’re approaching a mountain and you’re into the wind, you’re also in the down draft. If you do that, pretty soon you’ll find yourself looking up at the place you were going to land, instead of down at it . . . An awful lot of what I learned that first season wound up in the mountain training manual Okanagan produced, because I wrote a lot of it—but only after I’d discussed my experiences with Carl Agar. That was Carl’s great talent: he had a very special ability to talk to a pilot after the pilot had had some shaky experience and reduce it to its elements. He seemed to be able to see through what you were saying to the essence of what had happened. I guess this came from his long experience as an instructor. I think it was this ability to sort out the meat of an experience and then analyze it that made Okanagan Helicopters what it became . . .

I’ll give you one example. I had landed on a ledge at about 6,500 feet [2,000 metres] . . . jutting out from the mountain. There was a short cliff on one side and a sheer drop on the other, and the ledge would be about, oh perhaps 150 feet [46 metres] wide. I landed about 60 feet [18 metres] in from the edge on a nice flat spot . . . facing the cliff. What I learned then was that you never land unless you have figured out how you are going to take off again . . . But this time I did my jump takeoff too far from the ledge. The body of the machine was going to go over the edge all right, but I knew the tail wasn’t. I was already losing revs by the time I realized this. I shoved hard forward on the stick and then kicked on full rudder. I cartwheeled over the edge—cartwheeled so far that I was inverted at one stage and then I pulled out and got clean away with it . . . But after that I always landed very close to the edge of the drop-off, and I always jumped sideways off a ledge.12

In 1950 the provincial topographical survey, again headed by Gerry Emerson, carried on from the point where the previous year’s crew had left off, covering the area northwest of Kispiox, up the Nass River to Brown Bear Lake and into the valley of the Bell-Irving River. It began on June 1 with a flight from base camp to a site at the headwaters of the Kispiox River. The valley there is approximately 30 miles (50 kilometres) wide and broken up by a series of ridges and low hills with hundreds of small lakes. The Nass River flows through the western side of the valley, the Kispiox the eastern side and the Cranberry River forms the southern boundary. To cope with the difficult terrain, Emerson divided the area into five-mile (eight-kilometre) circles and positioned a survey crew in the centre of each circle to cover it on foot, taking barometric readings on all the lakes and meadows.

While fixed-wing aircraft brought in the equipment and supplies, the helicopter moved the five survey crews from one site to the next. As this meant the machine was flying every daylight hour of those long northern days and on numerous occasions the pilot also had to act as recorder for the surveyor, Carl and Bill split the flying duties. Sig Hubenig, who had been a pilot in the RCAF and worked for QCA as an engineer before joining OAS, carried out maintenance. To maintain the helicopter in serviceable condition, he carried out periodic checks each day, with Alf coming up from Vancouver to assist him with the hundred-hour check because this involved removal of the main rotors.

As the work progressed and the terrain gradually emerged from under the snow, it became possible to set up station cairns to assist with the work. Once each section was covered, crews re-occupied the control points that had been set up in the valley and the main triangulation stations in the mountains. During the Swan Lake base camp phase, the helicopter moved 18 fly camps over a period of 120 hours. On July 3 a QCA Norseman arrived to move the base camp to Meziadin Lake, and the pattern of work changed. Here the valley was narrower with ridge country behind it, making it easier for a single crew to handle the survey work while the other crews worked in the mountains. More food and gas stoves were needed as these camps were above the timberline, most at altitudes of 5,000–6,000 feet (1,525–1,830 metres), but the helicopter pilots had no difficulty finding good landing spots. Three weeks later the crews were repositioned partway between Meziadin Lake and the final camp at Bowser Lake where an additional 22 fly camps were set up in 90 flight hours. As the operation for the year moved into its final phase at Bowser, the mountain landings again became difficult due to more rugged terrain, and some of the 14 fly camps were exposed to high winds, which on one occasion destroyed a camp, leaving the crew to walk to the next camp for help. On August 3 visitors from the Forestry Service’s public relations department arrived to film the operation; their film was called The Flying Surveyors.

The skills and ingenuity of the pilots were often put to the test on this job. Few of the lakes in the initial area had suitable landing spots due to the heavy underbrush around them, although in the spring the nearby meadows made excellent landing sites. However, by mid-summer the grass had grown significantly, creating problems for the tail rotor-blade tips. This problem was overcome by having the helicopter hover over the grass while a surveyor used a machete to cut a 10-foot (three-metre) circle to allow the helicopter to land with the tail rotor in the centre of the circle. On one occasion Carl had to land on a tiny, isolated patch of ground just west of the Nass River. Unfortunately, the ground sloped away from it at a 45-degree angle, so the full weight of the helicopter could not rest on its wheels. Always resourceful, he had his passengers move to the front of the helicopter, then while it was in a hover, he guided it another foot forward to take the rear wheels off the slope. Afterwards, the front wheels had to be blocked to prevent the machine from rolling backwards.

The biggest challenge was the weather. At first widespread morning cloud and fog at high levels made it impossible to operate in the early hours of the day. But by mid-June the temperature rose to 100ºF (38ºC) each day, creating problems for the helicopter at high altitudes, and flights had to be restricted to early morning or evening. In July and early August they were plagued by winds and extreme turbulence, especially from late afternoon until dark, and at one point, all flights had to be suspended because landings were usually in tight spaces, often on the edge of a precipice. Fortunately, by mid-August the winds had dropped and flights could be resumed, but over the course of the project, they had lost 21 days on the job due to weather.

The season ended with the helicopter carrying out work on former survey stations and making reconnaissance flights to assist with planning for the following year. On August 17 the last crews were moved into base camp, and the following day the helicopter left for Prince Rupert. The machine had racked up 294 flight hours including ferry flights. Some days it had made as many as 25 mountain landings with 950 of the total at 4,000 feet (1,220 metres) or higher; the highest was at 6,700 feet (2,042 metres).

From Prince Rupert, Bill moved the machine to the Palisade project where he kept the “elevator service” to the dam site moving ahead of schedule and also managed to free up time to take on additional assignments. The dam contract was a resounding success, and the water board began considering a similar project at Burwell Lake north of Vancouver.

*

As Carl was nearing 50 and knew his flying days were coming to an end, he began looking for a pilot to replace him. His choice was D.K. “Deke” Orr, an experienced fixed-wing pilot who had flown charters on the BC coast. After Deke was checked out as a helicopter pilot on May 31, his first job was on a mining contract near Hope, BC, about 90 miles (150 kilometres) east of Vancouver. This is where the Reco Copper Mining Company was developing some claims on a mountain ridge above sheer rock cliffs that dropped 1,000 feet (300 metres) to the valley floor. Jock Graham, who went with Deke to carry out the maintenance, recalled:

When this mining promoter asked us for a quote and we said $100 an hour, he thought it was absolutely crazy. We pointed out to him that we were going to take 300 pounds [135 kilograms] in every 20 minutes, 900 pounds [410 kilograms] in one hour, which worked out at 11 cents a pound. That didn’t sound too bad.13

The scenery was beautiful, but the mine site lay between the jagged, snow-covered peaks of mounts Cheam and Foley on one side while Wahleach Lake and wooded hills separated it from the Fraser Valley to the southwest. As a result, everything the mining company needed had to be airlifted in, including a bunkhouse, its furnishings and supplies, mining equipment and crews. Deke, at the time still a novice helicopter pilot, had to deal with downdrafts and updrafts along the ridge as well as the fickle nature of the local weather conditions. Until almost the end of the year he shuttled back and forth every day the weather permitted, and in that six-month period, he flew approximately 80 hours, made about 200 landings and moved 35 tons (31.7 metric tonnes) of supplies, all of it to and from a helicopter platform located at the 6,500-foot (1,980-metre) level.

Two years later the project was still ongoing with a new pilot, Leo Lannon, who as a charter pilot had experience in the North and on Vancouver Island and was used to dealing with weather changes. As the mine had become fully functioning by that time, there were some changes in the type and volume of freight, though the procedures remained much the same. In 1952 Lannon submitted the following report describing his day’s work:

Off to an early start, the helicopter is loaded with 6 cases of dynamite, a 400-pound [180-kilogram] load for the first trip. The pilot hovers for a moment to check the load balance and then is away, climbing close in to a hillside searching for an assist from any updrafts. The air is unstable and turbulent. Up on the peaks, clouds seem to be moving in towards the landing spot. The weather is not very promising. Carburetor ice has been a problem in this area, and the pilot must be constantly on the watch for it. The helicopter, climbing steadily, is now in close to the glacial ice and snowfields with the cloud-ringed peaks towering above. The pilot is heading for the tiny landing spot on the top of the ridge at 6,500 feet [1,980 metres] where it joins Mount Foley in a sheer cliff. At 6,000 feet [1,830 metres] he passes below the landing spot and, glancing up, sees a man standing with his arms extended and his back to the wind. It is a reassuring sight. The pilot runs past a short way, makes a short 180-degree turn, still climbing. When getting close to the 6,500-foot mark and the final approach is made, the pilot gets set, ready for split-second action, slowing speed and gradually decreasing height. The helicopter arrives over the landing spot with inches to spare . . . All that is visible is the tall slim pole of the radio telephone antenna. The house that shelters the miners is more than 30 feet [nine metres] high but has long been buried in snows of another winter.

The landing spot has to be shovelled level by the men after each snowstorm and is only a shade bigger than the skid gear of the helicopter, the four corners of it being marked with something dark—10-gallon [38-litre] drums or anything handy. The snow has been so heavy this past year that the helicopter is now landing 20 feet [six metres] higher than the roof ridge-line of the house . . . The tail rotor of the helicopter is suspended out over 4,000 feet [1,220 metres] of space as the snow and mountainside drop away at a 60-degree angle. Two or three feet ahead of the helicopter, the snow and mountain also drop [a]way 3,000 feet [915 metres] at a 40-degree angle.

When unloaded, the helicopter lifts an inch or two and once more slips out into space for a downhill run for another load. The round trip from base to the mine site is 20 minutes. The cost runs 8.33 to 10 [cents] per pound to move freight into an area which is inaccessible to anything but a helicopter.14

Because the landing site was next to the Trans-Canada Highway, many people stopped to watch. For most of them, it was the first time they had seen a helicopter.

*

In July 1950 Carl received a phone call from W.G. Huber, president of BC International Engineering Company, to announce that the aluminum smelter project at Kitimat had been approved and to discuss a contract with OAS to provide helicopter support for the engineering staff who were to complete the previous year’s survey and install test towers for the power line. Carl was also assured that, once the main phase of construction began, OAS’s services would be required to support construction. At last he had a contract to take to the board to back his argument for more resources, especially more helicopters.

The Alcan project was made up of five massive construction sites, stretching across 5,400 square miles (13,985 square kilometres) of watershed from the Nechako River south of Vanderhoof to the Coast Mountains. It would link several large and many small lakes and rivers to create a series of dams and a giant reservoir. From there the water would be channelled into a 10-mile-long (16-kilometre), 25-foot-diameter (7.5-metre) tunnel through the mountains, dropping nearly 3,000 feet (915 metres) to a powerhouse blasted out of a mountain. The entire project depended on the successful construction of the transmission line linking that powerhouse at Kemano to the smelter at tidewater. While the data from the previous summer’s survey had pointed to a promising route, engineers were still concerned that the towers and cables would not be able to withstand winter conditions in the area, and they planned to construct a test line, which had to be in place by winter, only months away. The project involved erecting two sets of towers connected by cables. One set was to be built at 5,498 feet (1,676 metres), the highest point on the route, but when the rocky terrain at that level proved unsuitable, the towers were erected on a granite ledge 200 feet (61 metres) lower. The engineers were particularly interested in the degree of ice accretion that might cause the towers to twist and break, and measuring equipment also had to be in place to monitor this and other aspects of weather before men could be stationed on site during the winter.

With the topographical survey in the North over for the year, Carl left Vancouver in early September in CF-FZX and flew via Squamish, Lillooet, Williams Lake and Prince George to the Alcan base camp in a total flying time of 10 hours and 20 minutes. He went to work immediately, flying the surveyors over the proposed route and transporting the seven passengers and 19,300 pounds (8,754 kilograms) of freight required to set up the work camps at the base of Kildala Pass. After 40 hours flying time spread over 13 days, he returned to Vancouver for a major overhaul of the helicopter.

He was back in the Kildala Pass area by October 12. During his absence, construction crews had started to build a cabin at the lower test site to house the recording crews, and they had cut a trail between it and base camp for emergency maintenance during winter. Over the next eight days, Carl hauled the crew and all the freight needed to complete the tower construction and brought in the recording equipment. The towers, which had been prefabricated in Vancouver so they could be transported by helicopter, were delivered by ship to a large float at the mouth of the Kildala River where Carl had set up a base. One by one, the tower sections were strapped onto the carriers on each side of the helicopter and lifted to the construction sites. At the upper test site this required the helicopter to carry each load from sea level to 5,300 feet (1,615 metres). As the snow line was creeping steadily down the mountains, Carl was under a lot of pressure, but he completed the job by October 20.

*

Meanwhile, in addition to more pilots and engineers, the company needed more space, and they built a hangar and offices at Vancouver’s south terminal at a cost of $120,000. They also needed someone to run the office, a job that both Carl and Alf hated, and they were happy when the wife of a friend jumped at the opportunity. Ada Carlson stayed with the company as the executive secretary until her retirement in 1963. “It wasn’t much of a job to begin with,” she recalled, “just a corner of the old Queen Charlotte Airlines hangar. They didn’t even have a ladies’ washroom; I had to go across to the airport terminal.”15

Unfortunately, the vice-president of OAS, A.L. Johnson, died suddenly about this time. Although he had only been with them a few years, he had taken charge of operations, releasing Carl from the administrative duties. Now as well as resuming those duties, Carl continued his efforts to consolidate the company, lobby the directors for more equipment, prepare the operations manual and develop a syllabus for a flight-training program. He also contacted Bell about the shortcomings of the Bell 47 for mountain and northern operations—shortcomings that included the machine’s open cockpit, its under-powered 175-horsepower Franklin engine and wheels rather than skids. Because he had become recognized as an expert in mountain flying and OAS was one of the few commercial operators in North America, Bell listened to his advice. At the same time, a young helicopter designer named Stanley Hiller, whose Hiller 360 had been the first helicopter to fly across the United States back in 1948, had been working on a new machine that was similar in size to the Bell 47 and already included some of the features that Carl had recommended. However, after his initial investigation of the Hiller machine, Carl decided it needed more testing in the field and instead chose to continue pressing Bell for further improvements.

The early 1950s also saw the start of the company’s unique Mountain Flying School in Penticton. As soon as Carl had started flying in the mountains, he had realized how many of the parameters such as winds, air pressure, altitude, temperature and airflow impacted the helicopter’s performance, and he had begun taking detailed notes. Those notes and his experience as an instructor led to the development of a training manual and eventually to the establishment of a training school. In addition to 75 hours in the air and large doses of ground-school training, to graduate each pilot had to put in time in the maintenance shop working on the helicopters to become familiar with the mechanical aspects of the machine.

▲ Igor Sikorsky and Orville Wright in 1943 at Wright Field for the handover of the first VS-300 to the US Army. Photo courtesy of Sikorsky Historical Archives

▲ Igor Sikorsky wearing his famous fedora while flying the VS-300, which was first flown on September 14, 1939. Photo courtesy of Sikorsky Historical Archives

1951

With more work pending, in 1951 OAS acquired Bell 47 CF-FJA from Kenting Aviation, an eastern Canadian company, for the sum of $15,000; CF-FJA had been the first licensed helicopter in Canada. Carl also contacted Igor Sikorsky about acquiring two S-55s, which Alcan wanted to purchase because of their increased payloads. Sikorsky, one of the world’s great innovators in fixed-wing aircraft design, had built one of the first successful helicopters in the world, the Vought-Sikorsky VS-300, its single main rotor and small anti-torque rotor establishing the classic configuration for helicopter design. By 1942 a military version of the VS-300 was in production as the R4, but the machine really came into its own during the Korean War (1950–53) as the S-55. In 1951, when Carl approached Sikorsky, the S-55 did not have commercial certification and, with the military still absorbing all of Sikorsky’s output, none were available. However, he was confident that situation would soon change.

The new round of OAS recruits at this time included pilot Fred Snell, a former RAF wing commander who had flown just about every type of aircraft used for transport and combat. He had come to Canada after the war and held a number of jobs in the lumber industry and agriculture, ending up in Penticton where he met Carl, who hired him on the spot. Next came Pete Cornwall, a young fixed-wing bush pilot from Kamloops who had become enthralled with helicopters. Another highly qualified applicant, Don Poole, joined on May 18; an RCAF-trained pilot who had served with Bomber Command, Don later became the chief pilot of the Penticton Mountain Flight Training School, where he trained many military pilots.

On the engineering side, the company hired Bill Smith in April 1951; Bill went on to become chief inspector for Okanagan’s Vancouver base. The next hired was Gordon Askin, who had also trained in the RCAF and worked for QCA. In time Gordon would become the general manager of Canadian Helicopters Overhaul, the subsidiary company that specialized in component overhaul. Both men were highly qualified airline engineers who gave up secure jobs to become part of this new industry, one that challenged them with technology and terrain and required exceptional improvisational skills.

*

On February 11, 1951, Bill McLeod and Jock Graham set off from Vancouver for Kitimat in the open-cockpit CF-FZN for the 405-mile (652-kilometre), seven-hour trip to Kemano. En route they landed at the dock at Butedale (now deserted) on Princess Royal Island for fuel. While Bill went off to see someone, Jock waited on the dock. A local man came down to look at the helicopter, moved the cyclic and wandered around to where Jock was sitting.

Jock addressed him in the Hollywood version of an Indian lingua franca. “How!” he said. “Heap big machine, eh?”

The Indian studied the small Bell for a few seconds. “Mmm,” he agreed gravely, “but not nearly as big as the Sikorsky S-51.”16

It seems that an S-51 had landed on Princess Royal on its way to look for the 12-man crew of a United States Air Force B-36, en route from Alaska to Fort Worth, Texas, who had bailed out after their plane had lost two of its engines to icing.

Once at their destination, Bill and Jock were put right to work positioning the survey crews before the arrival of the construction crews who were building a 10-mile (16-kilometre) road from the powerhouse on the Kemano River to the Gardner Canal. Bill also flew the engineers in to check the test towers. Their base for all this work was a barge anchored in Kemano Bay, which, in addition to acting as a landing platform, provided very cramped living quarters and storage for the engineers and their equipment. OAS’s base was later moved to Base Camp Two, which was five miles (8 kilometres) farther up the river. Construction of the road from the bay to the powerhouse site, surveyed with the assistance of the photos taken by Professor Heslop the previous year, forged on rapidly while CF-FZN carried about 100 passengers and two tons (1.8 metric tonnes) of freight over 12 flying days.

March brought winds ranging from 50–100 mph (80–160 km/h), and temperatures dropped into the minus range. Deke Orr arrived to relieve Bill, and Alf came up to help Jock with a 100-hour inspection. Deke started work on the triangulation survey for the tunnel, which involved setting up 20 stations at elevations ranging from 3,000 (915 metres) to 7,200 feet (2,195 metres), and he completed the operation in 90 flight hours spread over 28 days. During this time the helicopter usually positioned survey teams in the morning and hauled freight and passengers between camps for the rest of the day; in one period of 76 flight hours they carried 126 passengers and four tons (3.6 metric tonnes) of freight.

Spring brought improved weather, allowing construction on the tunnel to start in June. The diamond drilling crew began testing the rock for the location of the powerhouse with the helicopters—a second OAS helicopter, CF-GZJ, piloted by Fred Ellis had now arrived—positioning men and equipment on wooden platforms at 800-foot (243-metre) intervals. Survey work on the road to Horetzky Creek was completed in 100 hours, a significantly shorter time than it would have taken the surveyors on foot.

▲ An early campsite in Kildala Pass during power line construction. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

The main camp, situated at the confluence of two streams and the Kemano River, was made up of rows of wooden-walled tents erected the previous year. Although it was set among magnificent snow-capped mountains, the view from the camp was composed of the muddy river and the low cloud banks hugging the slopes. This newly created settlement was a highly structured society where supervisors and workmen did not mix socially—with the exception of one place: Joan McLeod, the wife of pilot Bill and the only woman in camp, was an excellent cook and their tent provided a rare opportunity for everyone to socialize. Joan, who enjoyed being surrounded by interesting people, had been educated in Toronto but had grown bored with city life and taken a job with QCA in Prince Rupert. It was there she met Bill. After they went south to Vancouver so that Bill could train as a helicopter pilot, she was unable to find a job and, when he was assigned to the Kemano project, she joined him. Some of their recollections of that time on the Alcan project are contained in Helicopters: The British Columbia Story by Peter Corley-Smith and David N. Parker.

In the fall of 1951 [Bill McLeod] . . . was flying construction crews into the newly installed helicopter pads on the sidehills of the mountains. Work had begun on the tunnel from the west end of Tahtsa Lake and on the main excavation for the power house. The two helicopters, one flown by Bill, the other by Fred Snell, were constantly in demand . . .

Joan McLeod . . . heard a commotion outside her tent. She stuck her head out of the fly to see what was going on and saw the engineering supervisor spring towards her along the lane between the rows of tents.

“Where’s Bill?” he demanded as he reached her. “Fred Snell’s killed himself.”

“Fred’s not flying today—Bill is.”

“Then where’s Fred? Bill’s killed himself.”

Not surprisingly, Joan abandoned her cake[-making] and followed the supervisor in his search for Fred Snell. Failing to find him, they returned to the river where the accident had occurred. Standing on the far shore, looking depressed but obviously not dead, was Joan’s husband. After shaking his head, he turned and disappeared into the trees again.

Later Bill explained to the authors of Helicopters: The British Columbia Story that it had been raining so hard that day neither he nor Fred had flown:

Horetzky Creek, which flowed down into the Kemano River, was rising at a rate of about a foot an hour and a log jam had developed. They were afraid the camp would be flooded. A bulldozer went out to try to clear the jam and it dropped into a hole. There were three people on the “cat.” One fell off and managed to swim ashore; the other two were up on the canopy, ankle-deep in the water. The water was still rising and two of the supervisors came to me and said those guys are going to drown; you’ll have to get them off. So I said okay, but here’s where I made my mistake: I didn’t go over and tell those guys on the “cat” what to do myself—I told the others to tell them while I ran for the helicopter.

The story in Helicopters: The British Columbia Story continues:

The instructions Bill wanted relayed to the men on the bulldozer canopy were to wait until [he] had put one skid on the canopy then, and only after [he] had given them the nod, they were to climb into the helicopter, one at a time. Bill had taken the doors off, and when he got within two or three feet of balancing one skid on the canopy, one of the catskinners made a wild leap and grabbed the front of the skid. The helicopter dropped violently and the nose of the skids actually went into the water. The only thing Bill could do now was to pull up hard on the collective and twist on as much throttle as he could. But the weight of the man on the front of the right skid pulled the helicopter down and to the right. There was . . . “nothing on the right but trees,” and he went barrelling right into them.

“When the noise finally died down,” Bill recalls, “I was still 30 feet [nine metres] above the ground in the trees, inverted, swaying gently up and down and listening to the pitter-patter of the rain drops. The fellow who was riding the skid was still there; he was half in the machine and half out; he was sort of pinned. Of course, the bubble was gone and I noticed the battery was smoking . . .”

The over-eager passenger was unconscious. Bill’s first attempts to get him out of the machine failed. So he climbed to the ground and found a branch to use as a pry . . . He managed to work the passenger free of the helicopter, ease him onto his shoulder and climb down to safety. The passenger recovered consciousness a few minutes later, but they were on the wrong side of the river, and Bill emerged from the trees to see what was going on . . .

▲ Bell 47B-3 CF-FJA crashed into the trees while trying to rescue men from a flash flood at Horetzky Creek, Kemano, in 1951. Pilot Bill McLeod was not seriously injured. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

There were some 400 people on the far bank and they were in the grip of a remarkable panic. One man was rushing into the water with a first-aid kit. He would rush in until the water reached his thighs, realized that he couldn’t go any further, retreat to the shore, only to rush back into the water again, sobbing with frustration. A little further along, someone had backed a bulldozer with a logging boom on it up to the water. A man was standing on the logging boom with a coil of rope, hurling it towards the far bank. It never reached more than halfway across the river, but doggedly he retrieved it, coiled it and tried again. An hour later he was still doing exactly the same thing. “It was unbelievable,” Bill recalls. “All that crowd of people—it was mass hysteria.”

Joan McLeod, surrounded by irrational panic, finally did the one thing that is effective for hysteria. She ran up to the engineering supervisor and booted him as hard as she could in the backside.

Shocked, he turned to look at her. “What did you do that for?” he demanded.

“To make you start thinking.”

It worked. The engineer sent for a mobile crane. They strapped a large log to the boom, lowered it across the river and succeeded in rigging up a sort of boson’s chair that got Bill and his passenger back across the river safely, as well as the man still stranded on the bulldozer. Kemano at that time boasted a hospital of sorts and they were taken there to be treated. It turned out that Bill was more seriously damaged than his passenger. He had broken off the instrument pedestal in the helicopter with his shin, and he was in considerable pain and some shock. Fortunately, Bill’s injuries were not serious and he was very quickly back flying again.17

Joan continued to live in the camp, first in a tent and then a Quonset hut, through 1951 and into 1952. Life became much more complicated with the arrival of the couple’s first child in 1952. After the arrival of the second in 1953, Joan left the project for good.

▲ The Okanagan Air Services crew at dinner in the Kemano camp’s main cookhouse in 1952. The two men on the far left are Jock Graham (left) and J. Radovich (right). From left to right, the three men in the foreground on the right are Locky Madill, George Chamberlain and Bill Brooks. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

Gordy Askin, a helicopter engineer, arrived in Kemano to replace engineer Bill Smith an hour after that accident.

“Bill told me that the machine was stuck 30 feet [nine metres] up a tree and the pilot was okay,” Askin said. “With the help of a construction crew, we managed to get it down using a block and tackle.”18

▲ Gordon Askin, a young Okanagan Air Services engineer, outside the OAS hut at the main Kemano camp in April 1950. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

▲ The home of the OAS’s crew, in the Kemano camp. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

Two more accidents occurred that summer on the Kemano project. In the first a construction worker was seriously injured when he walked into the tail rotor of CF-GZJ. In the second, Fred Snell’s machine was badly damaged after it suffered an engine failure, and he autorotated into some rocks. He was unharmed, but the machine was badly damaged. Less than a year later Bill McLeod was involved in an accident that he was extraordinarily fortunate to survive. He told the authors of Helicopters: The British Columbia Story:

I was just heading back out of the [Kildala] pass when the machine started to develop a very heavy bounce; it was bouncing up and down about a foot, and it kept getting worse. I was about 1,500 feet [460 metres] above the ground when it started, and I set down as fast as I could. Then the bubble broke; finally, the engine quit and the tail rotor let go—it was bouncing so badly the tail rotor driveshaft tore right out of the transmission—and I had to dump collective. Even then, I was spinning. All the controls went; the whole bottom end of the engine fell out. I had cartons tied on the racks and they all flew off.

I was lucky, though, I hit on the only patch of snow in the whole area. It was about 80 feet [24 metres] wide and 100 feet [30.5 metres] long on a steep slope. I hit right in the middle of it. I slid down and hung up on boulders. Eighty feet farther on, there was a drop-off of some 500 feet [150 metres] down onto a glacier. When I stopped, I looked up and I could see the sun shining. I said, “Boy, that was a nice looking landing field!” Because I really didn’t expect to [get] out of that one.

Later it was discovered that Bill had cracked a vertebra, but his passenger had only cuts and bruises. Jock Graham, who was by this time Okanagan’s Kemano base engineer, was determined to find the cause of the machine’s failure:

It was a broken yoke [the hub on top of the rotor mast to which the main rotor blades are attached]. Bell had come out with aluminum yokes to save weight, and they sent out a directive that, if you ever had a blade strike, you had to throw away the aluminum yoke. We had bought the machine, JAA, from another company, and I went back through the logbook. Sure enough, I found an instance where they changed the blades. The obvious question was why had they changed them? It took me some time, but I managed to get in touch with the engineer working on the machine when they had changed the blades, and he admitted they had done so because the tip had hit an oil drum. They were a small outfit. They didn’t want to spend the money on a new yoke, so they didn’t throw it away.19

By this time, however, the helicopter crews on the Kemano job had more to worry them than accidents:

Their dissatisfaction was brought into focus by a recent immigrant who spoke little English and whose job was to clean up around the camp . . . The labourer had heard that the pilots were only earning $350 a month while he was earning over $500. Every time he saw the helicopter crews, he would shake his head and begin to laugh. And now that some of the initial glamour was beginning to wear off and the danger becoming more apparent, the helicopter crews grew increasingly resentful. They had played a vital part in the accelerated progress of the whole [Kemano] project and at the same time were the lowest paid employees. This, too, led to some lively exchanges between Carl Agar and his fellow directors down in Vancouver—particularly since profits, which stood at $10,000 in June, had risen to $58,000 by the end of August 1951.20

The problem was not limited to Kemano where at least they were fed and housed while on the job. On projects such as mining exploration and survey work in the bush there was another problem: although customers realized that helicopters were able to cover ten times the area and accomplish in one season what would have taken five, they were shocked with the $100-per-hour rate so they cut back on food, accommodation and supplies. Crews found themselves living in worn-out tents with little or no food. Fixed-wing re-supplies were kept to a minimum, which also meant lack of news and mail. Helicopter engineer Ian Duncan recalled: “No bread, no vegetables, no meat. I didn’t have scurvy, but I was awfully close to it. My gums were all sore and I lost 30 pounds (14 kilograms).”21

But there was good news for the company that year, too. At a dinner given in his honour on October 30 Carl was awarded the McKee Trophy, for outstanding service to Canadian aviation, which had also been awarded to his friend Wop May in 1929. Carl was also dubbed, in 1954, “Mr. Helicopter” by the Canadian Aeronautics and Space Institute. These events resulted in invitations to speak at the International Air Transport Association’s annual convention and the Helicopter Association of America in Washington, DC, where he met Igor Sikorsky for the first time.

1952

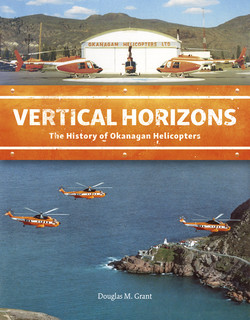

The company underwent another name change in 1952; it now became Okanagan Helicopters Ltd., a name that would last for the next 35 years.

During the year Alf began fitting skid gear and installing Plexiglas bubbles on the first Bell 47s. He also removed the covering on the tail boom, replaced the tail rotor skid and raised the fuel tank behind the rotor mast, converting these machines into 47D-1s, which were altogether more practical machines. Although the Kemano project remained the company’s major contract throughout this period, interest was coming from a number of other sectors, including several levels of government. Federal contracts called for a Bell 47D-1 to support marine research at Cape Harrison off the coast of Labrador and train coast guard and military pilots in mountain flying as well as provide support for a number of federal ministries. On the provincial level the company received inquiries for more topographic surveys and mining exploration contracts. As a result, tension between Carl and some of the directors resurfaced over the financing of additional helicopters.

Meanwhile, the company had grown so much that management needed more staff. Ada Carson was joined in the Vancouver south terminal office by bookkeeper Frances Heron, and, to relieve Carl of administration and operations duties, Glenn McPherson, whose background was in law, politics and business, was hired as vice-president and treasurer. On his first day he was the butt of a typical Okanagan prank: on leaving the office at 6 PM, he found his car stuffed with an inflated life raft. His struggle to open the door and insert the valve remover took quite a while and was observed by all the staff. But after he removed the life raft and returned it to the hangar, he announced that he had found a bottle of whiskey and invited everyone to have a drink. Then he was accepted.

Carl, free now to concentrate on training, produced the first manual outlining operational policy and maintenance and personnel procedures, and he began advising the militaries of both Canada and the United States.

*

▲ Carl Agar looks up at pilot Bill McLeod sitting in S-55 CF-GHV in 1952. Photo courtesy of the Kitimat Museum

At Kemano the three Bell 47s now stationed there clearly did not have the capacity to meet the project’s needs. While they had lived up to expectations, by 1952 the pressure was on for additional machines and staff. Alcan purchased two new Bell 47-Ds (CF-GZK and GZJ) and two Sikorsky S-55s (CF-GHV and CF-FBW) and gave Okanagan first option to purchase them. Unfortunately, the Korean War was still having an impact on the availability of additional machines and spares.

This expansion required the hiring of more pilots and engineers. The 1952 intake included pilots John Porter, Tommy Gurr, Bill Brooks and Fred “Tweedy” Eilertson and engineers Stu Smeeth, Keith Rutledge, Hank Ellwin, Ivor Barnett, Rod Fraser and Eric Cowden. Eric, who was another ex-QCA engineer trained in the RCAF, had managed QCA’s component overhaul shop. He had to get a Bell 47 licence before he went out with a machine, but the Ministry of Transport (MOT) did not have a licence program at that time. He recalled:

Alf Stringer said to me: “Take this manual home with you and study it.” The following week I went to the MOT inspectors [who were] also learning the mysteries of the helicopters as well.22

▲ Sikorsky’s “Mountain Men.” Photo courtesy of Sikorsky Historical Archives

In the spring of 1952 Jock Graham became the first Okanagan employee to attend the S-55 course at the Sikorsky plant in Connecticut. As it was nearing completion, Carl joined him to do a conversion course. About this time the first commercially certified S-55 went to Los Angeles Airways, but a tail rotor failure during a demonstration there resulted in an accident that caused several casualties and the grounding of the machine until Sikorsky could locate the problem and incorporate modifications. This accident delayed Carl and Jock in the east for another three weeks, but when they finally headed home with their first S-55, CF-GHV, they stopped in Cleveland to pick up Bill McLeod who had been in Toronto, and he completed his conversion training on the way to Vancouver.

When CF-GHV arrived in Vancouver on Saturday, April 24, 1952, the press was on hand, and the Vancouver Sun ran the following story:

Largest helicopter ever seen at Vancouver Airport landed today. A Sikorsky S-55 helicopter was flown from Bridgeport, Connecticut, by Carl Agar of Okanagan Air Services. The aircraft was for the Alcan Kitimat project.

The biggest “egg beater” ever seen at Vancouver whirled in at 100 mph [160 km/h] and dropped like a leaf on the runway. It took 35 hours from Bridgeport . . . to Vancouver . . . Carl Agar . . . himself was in high praise of the $190,000 aircraft.23

▲ Kemano base pilot D.K. “Deke” Orr (left) and engineers Jack Rich (centre) and Gordon Askin (right) with S-55 CF-FBW in 1953. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

By early May S-55 CF-GHV was working in Kemano, lifting men and material up to the Kildala Pass. Because of the loads it could carry, crews found it invaluable; it had only been in service a few days when it was called on to ferry drums of oil to a bulldozer that had broken an oil line while clearing snow at Tahtsa. CF-GHV was followed within a few months by the second S-55, CF-FBW, which on one occasion hauled over 123 tons (111.5 metric tonnes) of lumber up to the summit camps in 116 hours over 18 flying days. (When the load included 1,000 pounds (455 kilograms) of dynamite, the slings were set down as gently as possible.)

▲ A Bell 47 piloted by Tommy Scheer in Kildala Pass during the Kemano project. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

The first of the new Bells to arrive was CF-GZJ, which was to be used ferrying workers from Kemano to Tahtsa to work on the Dala River section of the power line. Due to weather conditions, the machine was unable to fly into the worksite and had to be hoisted by crane aboard the Nitnat, the Alcan workboat, for the journey upriver with pilot Don Poole and engineer Gordon Askin along for the ride. Once on location they operated it from a barge moored to the workboat. Soon after the machine arrived, alternate pilot Fred Eilertson was flying it to Tahtsa when he spotted a snow scooter upside down on the lake. Dropping down to investigate, he found a couple of badly injured men. He loaded the first on board and took him to East Tahtsa before returning for the second man whose condition was more serious. As the pass to Kemano was closed by the weather, he flew him to the Burns Lake hospital 100 miles (160 kilometres) away.

In June, Fred Snell and Carl arrived with the second new Bell, GZK, closely followed by engineer Gordon Askin. Next to arrive were pilot Leo Lannon and engineer Bill Smith to take over CF-GZJ, while Deke Orr and Gordon Askin returned CF-FZN to Vancouver to work on the Palisade project.

Heavy spring rain made it impossible to keep the Kemano road open. As a result, Okanagan was called on to move over 11 tons (10 metric tonnes) of freight and 390 passengers by helicopter, even flying out striking miners from the Horetzky Creek project. By May camps had been established along the transmission line with a fly camp at the summit of the pass, but with snow still on the ground, the pilots had to choose their landing sites very carefully. In some cases, the helicopter would hover above the chosen site while a man on snowshoes packed down a landing area and then set up a red wind flag. The first load always consisted of precut lumber, and this was followed by a carpenter and labourers to build a 20-by-20-foot (six-by-six-metre) landing platform. Only then could the machine begin to bring in the riggers to work on the transmission lines.

The work crews came to appreciate the helicopter’s assistance as they were able to complete their tasks quickly compared to past bush construction jobs. The story of “Smoke” Kole, the rigging foreman for Morrison-Knudsen, the company that built the transmission line, was a good example. When he first came to Kemano, he was afraid to ride in a helicopter and spent most of his time climbing up and down mountains and accomplishing very little. Finally, with many misgivings, he consented to ride in the helicopter, and as the summer wore on, he became a convert and was soon flying up and down the mountains several times a day. He told one of the Okanagan pilots that a helicopter was the answer to a rigger’s prayer as it was a lot easier to rig downhill than uphill. Instead of 75 percent of pay being spent on travel time, only about eight percent was charged by using a helicopter.24

During the summer, Art Fornoff, the Bell Helicopter representative from Los Angeles, visited the project and was so impressed that he phoned Bell’s head office (recently moved to Fort Worth, Texas) to arrange for Jim Fuller, Bell’s publicity agent, and photographer Tom Free to come to the Kemano project. When Free came back from taking pictures of the pass section, he shook his head and said in his Texas drawl: “Man, we have fellows back in Texas who think they can fly helicopters. Man, they ain’t seen nothing.”25

By the autumn of 1952 the road over the pass section was complete, and the passenger rate and amount of freight carried by Okanagan’s helicopters declined. On October 8 the diversion tunnel at Nechako was sealed off so that the reservoir could begin its four-year filling phase. A spillway system for returning spawning salmon had been installed at Cheslatta Lake, and Okanagan pilots Pete Cornwall and Lock Madill spend ten days taking officials around to check on the fish; Alcan was hoping that the fish population would increase due to changing the water’s direction of flow. By December a weather station had been established on the summit, staffed by three men and supplied by helicopter; they had a long-range radio and managed to keep current on local and world news throughout the winter.

1952 Annual Report

Since starting the Kemano operation the previous year, Okanagan Helicopters had carried out a number of medevac flights taking injured men to hospital and, as a result, the project had only one fatality. The period 1951–2 had seen flying time increase by 196 percent, flight hours by 204 percent, passengers by 212 percent and freight by 375 percent. At year-end the company’s annual report announced profits above $68,000, and the directors approved an order for a Sikorsky twin engine s-56. The civilian version of this machine, which had been designed for the US Marine Corps, was said to be capable of carrying 26 passengers. Unfortunately, the machine never materialized.

▲ Camp security at Beatton River, BC (northeast of Fort St. John), in 1953. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

1953

By the early 1950s the value of the helicopter had become widely recognized, and the industry expanded quickly. In the United States the 1,000th machine came off the Bell Aircraft assembly line, the new Hiller UH-12A was gaining in popularity, and Sikorsky Helicopters announced the construction of a new plant in Stratford, Connecticut, while on November 16, 1953, Igor Sikorsky was featured on the cover of Time magazine. In England, Westland Aircraft UK Ltd. signed a contract to build the Sikorsky s-51 under licence, and it went into commercial service with British European Airways (BEA) as the “Dragonfly.” The British company Autair Helicopters was formed, while Sabena Airlines of Belgium inaugurated a helicopter service from Liege to Brussels and began operating helicopters in the Belgian Congo. Within a few years the helicopter had become a fixture in the aviation world and the “eggbeater” nickname began slowly disappearing.

▲ Hotel Kotcho, Kotcho Lake, BC (east of Fort Nelson). Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

Although Okanagan’s involvement with the Kemano project continued throughout 1953, the company signed other contracts that year, including one supporting gravitational surveys for Imperial Oil in the Fort Nelson area, another that used Bell 47 CF-FZN with a Canadian Armed Forces survey team in Norman Wells, Northwest Territories, and yet another exploring for uranium using a specially adapted scintillometer, a device for detecting and measuring radioactivity. Farther south, Okanagan transported personnel and equipment during the construction of the 712-mile-long (1,145-kilometre) Trans Mountain pipeline running from Edmonton to Vancouver, and after it was completed in the fall of 1953, Okanagan was awarded the contract for routine inspections and other flight services. The inspections, carried out three times a month at 200 feet (60 metres), checked for rock slides, a common occurrence in that terrain. Later a new four-passenger Bell 47-J model provided an improved visual inspection platform for this work. In July Trans Mountain employed Okanagan Helicopters to install a special telephone line along the pipeline and place high frequency transmitters at Hope and Kamloops in BC and at Brookmere, Blue River, Edson, Jasper and Black Pool in Alberta.

▲ Engineer Frank Ranger with Bell 47 CF-FJA in a “maintenance hangar” in Kotcho Lake, BC, in 1953. Photo courtesy of Gordon Askin

On Vancouver Island pilot Pete Cornwall and engineer Sig Hubenig were assigned to a MacMillan Bloedel contract, at that time one of BC’s largest forestry companies, for the control of gophers and squirrels in the area of the Harmac pulp mill. The contract called for a helicopter, flying at 45 mph (72 km/h) at a height of 100 feet (30.5 metres), to seed bait over a logged-out 120-acre (48.5-hectare) section of rolling hills at Copper Canyon. The company borrowed Bell 47D CF-FSR, which was fitted with seeding equipment, from a pest control company in Yakima, Washington. When it arrived in Vancouver, it had to have floats installed before it could cross the Strait of Georgia, a 35-minute trip, and then on landing it was immediately changed back to skid gear. On MacMillan Bloedel’s recommendation, the provincial forestry department requested that additional seeding be done from September to the end of October.

Meanwhile, pilot Don Poole and engineer Eric Cowden were sent north with the brand new Bell 47D-1, CF-ETQ, for a job that was supposed to last ten days, but it was five and a half months before they returned to Vancouver. In an interview in May 2009 Eric described that season—his first—in the field:

In the spring of ’53, Don Poole and I set off for Stewart, right on the tip of northern BC about 900 miles [1,450 kilometres] from Vancouver . . . On the way . . . we had a terrific head [outflow] wind; we were so heavily loaded and on floats that I remember us chugging along at about 20 mph [30 km/h] into a stiff northwesterly wind when I saw two ducks fly past us doing quite nicely. We landed on the American side of the border, which we weren’t supposed to do, but we had to gas up somewhere. After refuelling, we set off up the Portland Canal. We were going nowhere, and it was one of those low overcast days, which means we could not climb out of the Canal and land. There wasn’t even a boat around—nothing.

Finally, Don said, “What do you think?”

I said, “Well, Don, my watch says we’re not going to make it.”

“You know what?” he replied. “So does mine.”

There was no place to land, so we just kept chugging along up the Canal, doing a little praying. Finally we turned a corner and got some shelter from the wind. When we landed at Stewart, I drained the fuel tank and we had two gallons [7.5 litres] left, enough for about six or seven minutes of flying.26

Their first job with CF-ETQ involved flying between Stewart, BC and the Granduc Glacier, the site of a copper mine that operated sporadically over the years due to the fluctuating copper market. On completion of that job, they moved on to other mining exploration projects and, as Eric recalled, that’s when things started to go downhill:

From Stewart we went [north] to Bobquin Lake with two geologists—MacKenzie and Warren were their names—who believed in living on bacon, bannock and beans with a little tea and sugar. That’s about all they had in their so-called camp. For several weeks we worked out of a little island in the middle of Bobquin. We stayed there for five weeks, and I’ll never laugh again when people make jokes about beans.

From there we moved to Hottah Lake and then on to Chukachida, more or less in the middle of the province. We were with some hotshot mining promoter now—I remember he was worth lots of money and behaved accordingly. The first day we were there he came into the camp in a beat-up old [Beechcraft] Travel Air . . . and the next morning the weather was socked right in, right down to the deck. I heard him say to the party chief, George Radisics, “What’s the weather like, George?”

And George said: “It’s socked in tight, but I think it’ll clear by noon.”

The promoter said, “That’s not good enough. I want it to clear now!” I guess he thought he could buy the weather, too.27

▲ Jock Graham during maintenance on S-55 CF-GHV, Okanagan Air Services’ first S-55, in 1953. Photo courtesy of the Kelowna Public Archives

Eric had other problems. The fixed-wing aircraft used on that operation, the hotshot promoter’s venerable Travel Air, was in sad shape, and the company operating it had not provided a licensed engineer. Instead, Eric was expected to inspect it and sign the logbook when it was due for its 100-hour maintenance check. However, every time the Travel Air, which of course was on floats, was pulled up onto the beach to be loaded or unloaded, he had heard what he described as “a funny noise.” When the time came for the inspection and his signature in the logbook, he got someone to grab the tail section and rock the machine up and down. Sure enough, one of the mounts on the struts that connected the floats to the fuselage was about ready to fall off. Eric refused to sign the log until the aircraft had been repaired—something that could not be done in the bush—and he was exposed to ferocious recriminations from the mining promoter. In the end the promoter and his crew took off in the Travel Air for Prince George, leaving Don and Eric sitting alone in camp for three days.

The next move for Don Poole, Eric Cowden and CF-ETQ was to Yehinika Lake, a little to the southwest of Telegraph Creek, BC. This was still Eric’s first season in the bush, and even though CF-ETQ was brand new, it was giving trouble:

We’d been having the usual snags with those Franklin engines . . . We were constantly having to change plugs and dig the lead out of the electrodes, and the fan belts kept letting go. When they did, they’d smack into the back of the firewall, scaring the hell out of the pilot . . . and then he’d have to get [the helicopter] down on the ground within a couple of minutes and shut down or the engine would over-heat.

Those were routine problems, but this engine began to give me much more [grief] than that . . . I thought the timing of the magnetos was out. Trouble was I didn’t have a manual with me on the trip, and this was a 200-horsepower engine. I’d been working on a 170-horsepower one, so I didn’t really know what the timing should be. I thought I remembered Sig [Hubenig] say it was 36 degrees—so I retimed the whole thing. It didn’t do a damned bit of good. Yehinika Lake was well up in the mountains, and we still had a very rough engine. I checked the plugs and points—re-set the gap—and everything was as it should be. Had me baffled there for a while. Then, when I was shutting down—I shut down with the mixture control—and just before the engine quit, it suddenly smoothed out.

So I fired up again and played with the mixture—we had a manual mixture control in those days. It would run fine just before it quit. I came to the conclusion it just had to be the carburetor. Trouble was I had never taken one apart before. I pulled the carb off the intake and split it, and out fell a little ball check-valve. It was a bad scene because I hadn’t the faintest idea where it had come from. I thought, Oh my God! Here we are, way out in the tul[i]es [bush] and our only way to get out is in that damned helicopter!

Anyway, I found the float level was way out, way beyond limits, so I set that all up. Now I really had to decide where this little ball had to go. In the end the only place that looked likely was the accelerator pump, so I popped it in there, clamped the carburetor together and bolted it back onto the manifold. When I fired up the engine, it ran like a charm. I didn’t bother telling Don about the worry-session with the check-valve. When he got back from a quick test flight and thanked me because the engine was running good, I just shrugged and said, “That’s what I’m here for.”28

Engineer Ian Duncan and pilot Mike McDonagh had a similar experience when they worked for the Canadian Army doing barometer surveys out of Puntzi Lake, about 50 miles (80 kilometres) west of Williams Lake. Ian Duncan recalled:

About a week after we’d arrived here, Mike took off with this lieutenant and his barometer and all his instruments and away they went. Be gone four hours, Duncan, he said . . . So four hours went by and then five hours, and I started to get up off my cot in the tent; I started to walk around the tent. By the time it got dark, I had worn a trench about two feet deep around the tent—just walking around . . . Finally, just after breakfast next morning, in comes [Mike] back to camp. He’d walked all night and you could see the blisters on his feet; his feet were bleeding.

It seems that Mike had been taking off from a little sand beach and tried to pull up too sharply and lost his revs. The helicopter had ended up in the lake. The Army lent Ian a four-wheel-drive Dodge Power Wagon, and “making use of the winch on the front of it, [he] hauled the vehicle through several swamps and forded rivers to get to the damaged helicopter. Then [he] used the winch to pull [the helicopter] up onto the beach.” Okanagan sent a new engine, and they proceeded to rebuild the helicopter right there.

About a month later they moved from Puntzi Lake right up to Satigi Lake, just south of Aklavik [on] the estuary of the Mackenzie River. A week after that, Ian recalls, the helicopter disappeared again:

“Mike went off on another of these barometer trips. He said he’d be back by four o’clock, but he wasn’t, and I wore another trench around my tent. It took us four or five hours to get through to Aklavik [on the radio], where we could get some help to go and look for him.”

Eventually a Beaver belonging to BC Yukon Air Services and flown by company owner Bill Dalzell was sent from Aklavik to Satigi Lake to start a search. The Beaver’s condition shocked Ian Duncan: “He had the most beat-up old Beaver you ever saw in your life. The rudder cables on the floats were so loose he’d tied knots in them to bring them up to proper tension. You couldn’t see the front of the engine for the bugs and oil and stuff. You’ve never seen such a shambles in your life.”

From the Beaver Ian spotted smoke and saw the undersides of two helicopter floats sticking up out of the water. This time Mike had been the victim of glassy water, and the machine’s floats had dug into the lake bed. He and his passenger escaped just before the machine turned over and sank.

Everyone was flown back to camp in the Beaver. Another Okanagan pilot, Eddy Amman, brought a replacement machine up from Vancouver. Meanwhile, Ian returned to the accident site in the Beaver, and after a struggle with come-alongs [manually operated ratchet winches], they managed to get the submerged helicopter ashore where they dismantled it, loaded the pieces into the Beaver and flew them back to camp to start the rebuild. Mike McDonagh was “given a rest” after this second accident, but it was merely a temporary setback for Mike; he went on to a distinguished career as a helicopter pilot.29

The living conditions in the camps continued to be appalling. Eric Cowden remembers that after Yehinika and Chukachida lakes, he and Don Poole were sent to Paddy Lake, about 30 miles (50 kilometres) south of Atlin, to work with a topographic survey crew:

Well, when you were at this camp at Chukachida, you were lucky to get a can of sardines thrown at you. And when we were ferrying from there up to Paddy Lake near Atlin—incidentally, by now the old girl was perking along fine, no plugs missed or twitches or anything—Don suddenly made like he was going to land. And I thought, I wonder what that old bugger heard that I didn’t hear.

Anyway, we landed in a moose patch, and I said to Don, “What the hell did we land here for?”

“Well,” he replied, “you and I have been out a long time. We’re going to take ourselves a couple of days off. We’re going up to Atlin.”

So we poured in our spare gas, and when we took off again, Don flew much higher than I’d ever seen him fly before, and we went right over Paddy Lake. Of course, there’s a brand new crew down there, all excited, all ready to go to work. They were waving frantically. We pretended we didn’t even see them. Old Don was a good 5,000 feet [1,525 metres] [up] and we just chugga-chugged right up into Atlin.

The first thing we did in Atlin was to go to the café and order lunch, and the first thing I ordered was a salad.

“Aren’t you going to have a steak?” Don asked.

“Yes, later, but I need to start with this. I think I’m getting scurvy. My gums are all sore.”

“Me, too,” said Don. “That’s why we’re here!”

We lived like peasants out there in those days. It was expected of you, part of the job, so you accepted it. Changed days now; nobody’ll do it anymore.30

Eric Cowden also remembered the mixture of anxiety and boredom on the job. He spent most evenings doing maintenance under constant attack by mosquitoes and blackflies, but during the day when the machine was out flying he had nothing to do:

You could usually fish and walk around the shore of the lake, learning something about the vegetation and the animals, but most of the time it was sheer boredom. You had nobody to talk to during the day but the cook, and he was nearly always a cranky old bastard. I tell you, I’ve read thousands—and I mean thousands—of pocket books. In fact, I can pick one up even today and probably go through the first paragraph and say, “Dammit, I’ve read that one!”31

Later that year, Eric was sent on the S-55 course, the only civilian in the class:

I had the instructors at Sikorsky breaking down the engine, gearbox and transmission and anything I felt that I would have to repair in the field. The military guys were not happy campers as it added a lot more time on the course and took up the instructors’ time. The military guys were just used to changing parts, which they had many on hand. I was going to Kemano and would need all the information on the S-55 that I could get. I tried hard to beat Sig Hubenig’s course marks but he beat me by one mark. That’s why I guess he was my mentor.32

Eric Cowden became the base engineer of the Kemano project, in charge of the S-55s as well as the Bell 47s. By that time Bell CF-JJB had been involved in various accidents and rebuilt a number of times, whereas JJC was accident-free, and pilots noticed that JJB’s performance always lagged behind JJC’s. This really bothered Eric, so he changed all JJB’s components including the engine, swash plate and transmission. However, he could never get that machine to perform as well as JJC.

Okanagan’s first S-55s were leased from the RCAF and, though they had the Okanagan name on the machine, they still retained the RCAF logo on the tail boom, which shows up in photographs. Eric recalled:

Bill Brooks used to say to me, “Eric, the 55 is a great machine. Throw in the grease, the oil and fuel, kick the tires, and she will never let you down.” He just loved that machine. I remember one incident, though, in Kemano. To get the machine in the hangar, you folded the blades, and it was the line engineer’s job to ensure the locking pins were in when the machine was doing a trip. I guess [Bill] must have missed one [on his pre-flight inspection] because, when he started up the machine, he chopped off the tail boom. The engineer sure got heck for that and sure felt bad about it.33

1954

For Okanagan Helicopters the year 1954 was very eventful. The company introduced a newsletter and established the Penticton Mountain Flying School, which is still in existence. The company’s machines carried out several medical emergency flights while working with Newfoundland’s Department of Fisheries, flew the Duke of Edinburgh from Kemano to Kitimat and Governor General Vincent Massey around Vancouver Island. Carl undertook a promotional tour to the USA, UK, Europe and New Guinea. In addition, the company began work on a new Vancouver airport facility at 4391 Agar Drive in Richmond with 10,000 square feet (930 square metres) of hangar space and 5,000 square feet (465 square metres) for offices. It would remain the company’s head office until 1987.

▲ Despite some success in the early 1950s, Okanagan still faced financial problems. Alf Stringer looks to Carl Agar for more money for spares; Agar, in turn, questions company president Glenn McPherson, who shows them his empty pockets. Image courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives, Fonds PR-1842

As work on the Kemano project wound down, Alcan cut its operating fleet to one S-55 and two Bell 47Ds, releasing the remaining S-55 and two Bell 47s for purchase by Okanagan, the S-55 going for $115,000. Fortunately, offsetting the loss of revenue from Alcan, the company received numerous inquiries from all over Canada and the US, including one for a geological survey in the Harrison Lake area of BC for the Dominion Exploration Ltd., a scintillometer survey of the North Thompson River for Warmac Exploration, and a freight lift operation in the Anyox area, 37 miles (60 kilometres) southwest of Stewart, BC. As a result of all this interest, management decided to set up two new subsidiaries to handle the workload. Agar Helicopters Consultants Ltd. would deal with both the Canadian and US military, and Scintillopter Ltd. would provide airborne Geiger and scintillometer surveys for geological exploration.

When the Kemano project was winding down, Carl released the following operational facts:

| Flying | 2,203 days |

| Helicopters in service | 4,551 days |

| Number of trips | 21,722 |

| Platform landings | 18,561 |

| Number of landings | 42,021 |

| Passengers | 20,433 |

| Freight | 2,008,405 pounds [91,0997 kilograms] |

| Air miles | 6,214.25 [10,000 kilometres] |

About that time all the S-55s in North America were grounded because of a manufacturing mistake. Jock Graham, who had left Okanagan to become a technical representative for Pratt and Whitney, discovered the mistake. He had been called to a mining camp in the Yukon to solve a problem with an S-55:

The pilot, Russ Lennox, kept having the engine almost fail. It looked like fuel starvation. He would land, shut down and then start the engine again, and everything would be good. He’d come back to camp, and the other engineer and I would just about tear the whole fuel system apart, and we couldn’t find anything. I was baffled. Then one day we were sitting around with all the screens [filters] out of the fuel system. One of them was a finger screen—a hollow tube with a fine mesh screen like a thimble on top of it. The mechanic from the Otter we were using picked it up and tried to poke a piece of grass up through the bottom hole. The grass wouldn’t go. When I had a good look, I found there was another very fine screen in the hole, where it certainly shouldn’t have been. The people who had made the filters for Pratt and Whitney had misread the drawings and this extra screen was causing the fuel starvation. So we had to ground every S-55 in North America until the second screen had been punched out.34

Another first for Okanagan was a contract at Fort Good Hope, 90 miles (145 kilometres) northwest of Norman Wells, where local game warden O. Eliason wanted to carry out a survey of the beaver population in the Hume River watershed, which was reported to have the richest beaver stock in the Northwest Territories. The survey had to take place in late August or early September due to the beavers’ habits. The project, undertaken using a Bell 47 flown by J.P. Smith, required about 30 hours flight time to cover approximately 2,500 miles (4,025 kilometres), flying tracks a mile apart over 50 square miles (80 square kilometres). This was the first beaver survey in the area and certainly the first anywhere using a helicopter. With the success of the survey, similar studies were proposed for other areas.

Rumour had it that Shell Oil was doing exploration work in the Mackenzie area and needed something larger than a Bell 47. Jock Graham arranged a meeting with the executive assistant to Shell’s president and their chief pilot and suggested they call Okanagan. That call resulted in a three-month contract for the S-55 with pilot Bill McLeod at the controls. It was, Bill reported, the most enjoyable job of his career:

That was the first year that Shell had used a helicopter. They got a 55 and a Bell and I flew the 55. We did a preliminary geological survey of the Mackenzie Mountains, starting at Fort Liard and working our way not quite to the Arctic coast. We were back in the Richardson Range by the time we finished up.