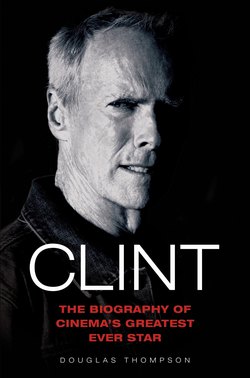

Читать книгу Clint Eastwood - The Biography of Cinema's Greatest Ever Star - Douglas Thompson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеThe Numbers Game

‘Life? It’s all improvisation.’

CLINT EASTWOOD, 2003

AGE? Just a number?

Clint Eastwood was 75 years old on 31 May 2005.

Old?

Yes, by the calendar; no by the attitude.

‘I’m just a kid, I’ve still got a lot of stuff to do,’ he said a few weeks earlier, his hands weighed down by the couple of Oscars he clasped like workout weights. You need a little more than daily exercise to be able to deftly handle the Academy Awards, to deal with fame adroitly. Yet, by the look of Clint Eastwood, he could bench-press many more fistfuls of the gold-plated, 13½-inch tall statuettes, which undergo a remarkable metamorphosis when placed in the right hands.

Which he might do in 2006 with his film version of Flags of Our Fathers, the hugely praised account by James Bradley detailing the battle of Iwo Jima in the Second World War. He’s only going to direct and co-produce that film, not act in it. It should be released in cinemas before his seventy-sixth birthday. Yes, he’s still ‘got stuff to do’.

Clint, the man renowned for being cool and laconic, slow and easy, liberal with his attitude and judgements, is always in action. Watch his face, his sparkling, bright-green eyes especially, and his interest is everywhere. He’s his own software program. He gathers all around him and then logs on to his singular inquisitiveness. Every book, documentary, news event, man, woman, child, local event and turn in the road is an opportunity to tell a story and most surely to write a song or a movie soundtrack. It is, as he always says, all about improvisation. Life, he also insists, is where you are constantly adjusting to everything.

So, as far as he’s concerned, numbers, even intimidating ones, don’t comprise a large part of the equation. But at the Kodak Theatre in Los Angeles on 27 February 2005, they came into play like the lottery.

Clint and Million Dollar Baby, which he called his ‘humble movie’, were in contention for top honours. The main opposition was two first-class pictures, both biographical: Martin Scorsese’s big-budget Howard Hughes saga The Aviator and the admirable Ray by Helen Mirren’s husband Taylor Hackford, the story of music giant Ray Charles. Also in the running at the annual cavalcade of self-acclaim were Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake and Alexander Payne’s amusing, with a hint of boldness, wine-soaked Sideways.

The 5,808 Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences voters made Clint’s day. At 74 he became the oldest director to earn the top honours as Best Director. He’d previously won the Best Director trophy for Unforgiven in 1992.

Numbers? Interesting ones. With television viewers turning off worldwide, the Oscars producers wanted a younger, hipper image, which was why Chris Rock appeared as the host of the 2005 Awards. Hip? As it turned out, some of the big winners might be candidates for hip replacements.

Eastwood directed his first film three years before Hilary Swank, who was named Best Actress for Million Dollar Baby, was born. He displayed both his long-matured cool and his elan when he was named Best Director. The slightly less veteran Martin Scorsese, then 62, lost his fifth nomination for the award in what had been the most hotly contested and watched conflict of the 2005 Oscars. It was the victory of a small, intimate character piece over The Aviator, which, true to the extraordinary life and legend of Howard Hughes, was a super-sized, $110-million extravaganza of Hollywood movie-making.

Numbers?

Clint thanked his mother Ruth, then 96, for her ‘genes’ and pointed out: ‘I’m happy to be here and still working.’ He then expressed his gratitude to a long list of veteran collaborators, including production designer Henry ‘Bummy’ Bumstead, aged 90 in 2005 and winner of two Oscars, for To Kill a Mockingbird and The Sting, whom he described as a member of ‘our crack geriatrics team’.

Who, to use the vernacular of Million Dollar Baby, were in Clint’s corner. The contest between front-runners Scorsese and Eastwood proved to be the evening’s only true nail-biter. These two well-respected men embody different strains of Hollywood film-making: Scorsese, the diminutive, fast-talking Italian New Yorker, was an enfant terrible of the 1970s who spearheaded one of the greatest periods in American film with such intensely personal, super-macho stories as Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. More than 30 years later, when most of his auteur comrades had faded from the scene (with the entertaining exception of Steven Spielberg), Scorsese devotes himself to visually flamboyant historical pageants like Gangs of New York and The Aviator, both of which featured Leonardo DiCaprio.

In the other corner was ‘Dirty Harry’, the film star who also became a director in the 1970s with movies like Play Misty for Me and The Outlaw Josey Wales. At that time Eastwood was largely derided by critics as either a crypto-fascist or a dud; arguably because of the single-minded New Yorker critic Pauline Kael, who attacked the original Dirty Harry for its ‘fascist medievalism’ and ‘remarkably single-minded attack on liberal values’. This critical contempt for the five furious, Magnum .44-driven Dirty Harry Callahan movies only dissipated, and even then not in all circles, with 1992’s Oscar bonanza, Unforgiven.

Eastwood, still angered by what he saw as Kael’s bigotry, says of the series, films that created their own genre: ‘I was playing a part. I’m an actor playing a role and if somebody thinks I’m supposed to be that guy, then great. You have to put yourself in the roles, and if you put yourself into them positively enough, strongly enough, people believe you are this person. It’s a fantasy. But it’s a fantasy the audience wants to believe.’

Of the now-dead Kael, he was asked if she did him real damage. He softly replied: ‘No, no. I’m still here. And she’s not.

‘Kael was saying I was a product of the Nixon years – that I represented Nixon. But I was doing very well as an actor long before Nixon became President. And I was doing well after Nixon. And somebody else said: “Well, he’s an actor of the 1980s.” But the 1990s and onwards have been some of my best years, so I don’t know where all these experts come from.

‘I just went ahead and did my own thing.’

Since Unforgiven he has told his stories tersely, with creative economy and increasingly lean budgets. In Scotland’s canny capital, Edinburgh, they’d build this fast and frugal man a monument. Clint, who is at his happiest at the piano and loves the blues, wrote and played those films’ jazzy, melancholic scores. In the 21st century he is a Hollywood legend, one of the most consistent top attractions in the history of the movies, and on the marque with Clark Gable and Gary Cooper and John Wayne and Paul Newman in terms of star longevity.

Eastwood won this particular Oscar contest. Scorsese is not giving up, and a cinematic rematch is on the way. In 2006, when Flags of Our Fathers will be in contention, so will he be with The Departed, an Irish gangster story starring DiCaprio, who seems to have taken Robert De Niro’s place in his repertory company, and the non-retiring, in every sense, Jack Nicholson.

Nicholson? He’s a number too.

In the early 1990s he and Eastwood were playing golf together and they talked about retirement. Eastwood recalls: ‘Jack said he was going to do just one more movie, The Crossing Guard, and that would be his last. I said I would do In the Line of Fire and A Perfect World and that would be it. Well, he went on to act in about ten more movies, and I went on to act in or direct six more. They keep saying yes to you, so you keep on going.’

Yet Million Dollar Baby, which many prominent people rate as Eastwood’s greatest work, was a film the powers that be in Hollywood were not too keen to say yes to. It was one of the hardest ‘sells’ of his career, and this baby was nearly never born. Especially as an Eastwood film. At an early stage in the film’s development, Arnold Schwarzenegger, 2005’s Governor of California (a job you could have bet on Clint getting a couple of decades ago), was considered for the role of the boxing trainer played by Eastwood; Sandra Bullock was once the favourite for Swank’s part as a boxer in search of a mentor.

In another incarnation it was to be an HBO TV mini-series or an independent film directed by Clint’s friend Anjelica Huston. Then, Hollywood happenstance. It happens. Million Dollar Baby proves it, along with so many other things. Life, even the movies’ version of it, can be changed by serendipity. In this case, both at the same time.

Jerry Boyd, a Hemingway wannabe, was one of life’s rejects. His three wives had thrown him out, publishers didn’t want his stories, written as Francis Xavier Toole, and he was scuffling a living working in a boxing gym in Los Angeles. And writing his short stories; his collection Rope Burns was finally published in 2000, when he was nearly 70.

Then a dead man gave him a little luck. But just a little. The influential Hollywood producer Al Ruddy had cast the late actor Al Lettieri as Virgil ‘The Turk’ Sollozzo in The Godfather in 1972. Ruddy was asked by Anjelica Huston to meet Boyd to discuss his short stories.

Boyd was a friend of Lettieri’s and when he met Al Ruddy he mentioned the name. ‘I said: “Let’s go and have a drink at the Havana Club,”’ recalls Ruddy. ‘He said: “I can’t, I’m in Alcoholics Anonymous.” I said: “So, you’ll have a Coke and I’ll have a drink.” Needless to say, we both drank until 5am.’

But Huston had moved on to work on a project with Mrs Hollywood, Julia Roberts. Nevertheless, Ruddy made Boyd’s dream true and bought the rights to his stories, a month before Boyd died from a heart attack in September 2002.

The project went ahead, which is where Paul Haggis, a creator of the television series Walker, Texas Ranger, came in. He told Ruddy he would write a movie script for Million Dollar Baby – if he could direct it. The script, an adaptation of two of Boyd’s stories, was then shown to Tom Rosenberg’s Lakeshore Entertainment, who were enthusiastic. Hilary Swank and Morgan Freeman were set up as the stars. Ruddy then showed the script to his old friend Clint, who said he had all but retired from acting. Nevertheless, Clint read the script as a favour to Ruddy and liked it; he was just concerned how it might be directed.

Although he’d sworn he would never again star and direct a film at the same time, he asked Ruddy if he could direct. Haggis, who was nominated at the Oscars for his script, said: ‘It was a tough ten minutes for me. I decided, of course, I would let him direct. How often do you get to work with Clint Eastwood?’

But it was no first-round knockout. Warner Brothers, Clint’s long-time studio home, initially declined to participate, worried that boxing movies weren’t commercially viable. They thought the script ‘too dark’ and the comparatively modest budget of $30 million ‘too high’. The rejection came despite the fact that the Eastwood-directed Mystic River was one of 2003’s best-reviewed films and a box-office hit for the studio. Lakeshore Entertainment agreed to bankroll Million Dollar Baby and, after other studios passed, Warner Brothers relented and agreed to share the film’s cost.

Unlike most movies that are put through endless rewrites, Clint filmed the first and only draft of Paul Haggis’s script in 37 days, working in and around the vibrant downtown area of Los Angeles to tell the story of cantankerous – is there any other sort? – boxing trainer Frankie Dunn.

And of the ‘Million Dollar Baby’. Dunn runs a haven for hopefuls and puts up with the hopeless. Morgan Freeman, as former boxer Eddie ‘Scrap Iron’ Dupris, helps him with the job, which suddenly includes looking after the fortunes of Maggie Fitzgerald, played by Hilary Swank. Maggie wants to fight her way out of dire straits with self-justifying success in the ever-more popular discipline of women’s boxing.

So far, a boxing movie with a twist in that the contender is a woman. But there’s more to it than that, which is why Eastwood got involved. ‘I’m at an age in life when I’m not trying to do things that I did years ago. I’ve tried to shoot my persona down so many times. I’m looking for different stories, stories to go with the maturing of the years. I probably would have retired years ago if I hadn’t found interesting things to do.’

This was interesting. And it got more so as the Oscars for 2005 approached. There had been Golden Globe awards and many other critical and endorsing honours, but then Clint was accused of being a soft-hearted, left-wing sympathiser.

Hey, this was the man who at the height of anti-Vietnam protest supposedly supported President Richard Nixon. He also backed Ronald Reagan, who borrowed his fellow actor’s catchphrase ‘Make my day’ for a colourful stand-off with the US Congress in 1983. Around the same time Eastwood phoned President Reagan to lobby for White House support to send a team of mercenaries into Laos in search of long-missing POWs. Even after Reagan refused, Clint was said to have helped to fund two such missions.

Left-wing extremist? Yes, according to high-profile right-wing commentators who attacked Baby for spreading ‘liberal propaganda’ behind the smokescreen of a sports drama. Their argument was that the film’s downbeat conclusion was an apparent endorsement of mercy killing. Not to Clint: ‘I never thought about the political side of this when making this film. How people feel about that is up to them. I’m not a pro-euthanasia person and this is a story about a giant dilemma and how one person had to face that.’

Later he said of the controversy: ‘I’ve had them work me over before.’ And of the honours: ‘It’s very nice. But I just do what I feel like I should be doing and whether you are nominated for something has never been the motivating force for me. It’s in the eye of the beholder, and once you finish a film, in a way, it doesn’t belong to you any more, it belongs to the audience to interpret it in the way they feel like interpreting it, and that goes for whoever is nominating whatever. You can’t make movies thinking about that.’

He calls where he is in life ‘the back nine’ and he does enjoy his golf, although he qualifies this: ‘I like playing golf but I don’t want to have to play golf. I like work. I’m involved. That challenges me. I like playing golf as an avocation – but while I’m good at it, I’m not talented at it. And I keep getting offered things. There’s always a new hurdle.

‘I love the spirit of acting, I love to watch actors, I love to direct them. I probably, in my mind somewhere, could have retired from acting a long time ago if somebody had said: “OK, that’s what you should do.” But then, you know, there’s always some fool out there who wants you.’

He also likes doing his business deals with the help of his agent-business manager Leonard Hirshan, who first began representing him in 1961. Many years later, in 2005, they were both happy with a scheme to use Clint’s image on gambling machines to be set up in Las Vegas. The name?

‘They wanted to make one called “A Fistful of Dollars”, which is a great title for a slot machine,’ says Eastwood. ‘And then there’s “A Few Dollars More”. You get the picture. They already got a Marilyn and a Bogart.

‘Maybe I’m the only one alive, though.’

And kicking.