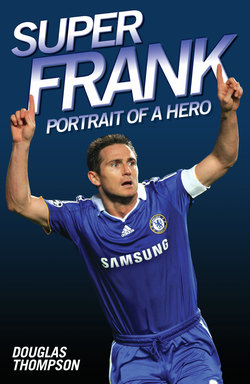

Читать книгу Super Frank - Portrait of a Hero - Douglas Thompson - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Daddy’s Boy

‘Dad has been the biggest influence of my career. If I had a bad game for the school team, I’d get stick off him.’

FRANK LAMPARD JUNIOR

Young Frank Lampard had no need to use football as a path out of inner-city poverty or problems. His father’s financial diligence had taken care of that. Remember, with the Lampards it’s football and family and vice versa.

‘Dad had to wait a long time to get a son. I have two older sisters and, when I was born, I reckon he just threw the ball at my feet and said, “That’s a football – kick it.”

‘I had a lot of football knowledge pumped into me from an early age, but the other side of the coin of having a father with his record is that you tend to be very self-critical.’

His father says he took to football ‘like a duck to water’, but he’d seen other youngsters’ careers collapse, so he arranged for his son to have a private education. At Brentwood School, Frank Junior applied himself as much to the books as to sport; he did exceptionally well at cricket and as a very young lad was playing on youth soccer teams.

He went from kicking a ball around the garden at age six to Sunday-morning games with kids two and sometimes four years older than himself. If he’d been a swimmer they’d have chucked him in at the deep end.

‘Frank never came to me and said he wanted to be a professional, it was one of those situations that just developed over the years. As an ex-pro, the first thing you want is for a son to kick a ball. His enjoyment was so obvious. Give him a ball and he would carry on until he dropped.’

He went on to play for Heath Park at youth level and there the parents of the other players complained that he was only in the team because of his father, because of his name.

It is one thing to take all the sticks and stones going at professional level, but suffering the smugness and stupidity of the small-minded needs anger management. Frank does it his way: ‘I still feel that I am proving these people wrong whenever I go on to the field.’

And there were always pressures, ‘Dad doesn’t often show his feelings. He manages to get his point over pretty well, though. He’s my biggest fan and my biggest critic. He always will be. We’ve had countless rows and arguments, but afterwards I usually realise he’s right.

‘There were times at home when we’d row over football because I refused to see things his way. I’m one of those blokes who says what he feels; I don’t see any point in holding back.

‘I know some of the things I’ve said to him have hurt like hell and I think, Oh, my God, what have I said? But when I’ve gone off and cooled down a bit, I admit to myself he has been in the game too long to be wrong too many times.

‘He’s still a bit of a hardman, a difficult taskmaster who strives for perfection. That bit rubbed off on me. I want my game to be perfect and I always want that bit of steel my dad had in his playing days.

‘Being hard doesn’t come naturally, but I have learned how to be strong, both mentally and physically.

‘The rest of the family, my sisters, my mum, have also been a support. It was always football, football at home and sometimes it would do your head in. I’d go and talk to mum just to get a release.’

You can understand. For the family it has been a football world for a long, long time. Other matters were kept private, known only to a tiny inner circle.

Pat Lampard has been the perfect matriarch, knowing the family, their secrets, their foibles, strengths and weaknesses. She has held it all together over the years. She has the perfect personality for it. She also has a pragmatic sense of humour about the family circle.

When Frank Junior was excelling at cricket at Brentwood School, there was much talk of him becoming a professional cricketer, even of representing his country. He was that good. There were moves by coaches from the South of England Independent Schools to enlist young Frank as a future cricket star. It led to a front-room talk between mum and dad.

‘Any question of football or cricket?’ Frank Senior was asked.

‘The boy can do what he likes,’ said his father who walked out the door. About thirty seconds ticked away.

Then the door opened and Frank Senior’s head came around it and with a smile he added, ‘He can do what he likes as long as he plays football…’ The family business.

Harry Redknapp joined the Hammers, aged seventeen, as an apprentice in 1964. ‘I lived in the East End. I was born ten minutes from the ground; Bobby, Geoff, Martin, Frank and Trevor Brooking, they all came from within twenty minutes of the ground.’

Frank Senior was eight years old when he first started kicking a ball at Upton Park and fifteen years old when he was being coached by the legendary Ron Greenwood (‘the only one great coach’, according to Harry Redknapp) at West Ham. Then, the insistence and thrust of training was on invention and speed of movement – the traditional qualities of the club.

His son signed his Youth Training Scheme papers with West Ham, ignoring the temptations of Arsenal and Spurs, on 1 August 1992, when he was close to the same age.

‘I wasn’t even working with West Ham when he decided to sign his YTS forms – he made the final decision to play for the Hammers,’ said Frank Senior, adding, ‘He was very lucky. A lot of my old mates from Canning Town still watch West Ham from the terraces. All of them were football nuts, just like me, desperate to play for the local side. I managed to get there.

‘I felt I was representing them, those blokes who wanted to be out there on the pitch busting a gut for their club.

‘The same thing happened to Frank. A lot of his pals stood on the same terraces doing exactly the same as my mates. Frank realised he was their standard bearer – he wanted to give them his best, just as I wanted to give them mine.’

His son revealed, ‘I nearly went to Spurs, but in the end I chose West Ham. It was the club I supported, after all.’

And there were family ties. Harry Redknapp moved from Bournemouth in 1992 to become assistant to manager Billy Bonds at West Ham. He’s addicted to the game and team control, although he warns, ‘In football management, you can leave home full of the joys of spring and come home in despair and, if you don’t feel like that, you shouldn’t be in it.’

His nephew found out quickly how much jealousy is around. Even then it was something of a curse to be Frank Lampard Junior, even though his father had left the club seven years earlier. And he was still small for his age and could not get around the pitch as much as he would have liked. That changed.

Frank Lampard Senior was a successful businessman with a thriving property business; the family home was a smart, large house in Romford, Essex, but even as a young teenaged trainee there were lads telling him he was only there because of his dad.

He’s a proud man and was a proud boy: the criticism and sniping upset him, but he kept his rebellion against his tormentors within himself; he learned early to keep his most dramatic ups and downs and his thinking as private as possible. As would become the norm, he just worked harder to prove his right to be in the stimulating environment of the West Ham ‘Academy’.

There had been some famous graduates, most memorably the 1966 World Cup trio of Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters of whom, for many, Frank Junior brings back many footballing memories.

With his great friend Rio Ferdinand and Trevor Sinclair, Frank Junior comprised, nearly four decades on, a superbly talented reminder of the glorious ghosts of the past. Of course, by then it could also have been called the Fame Academy.

Harry Redknapp has always made a great deal of ‘his’ boys nourished at West Ham United. In 1994, when he took over as manager from Billy Bonds, he brought back a former graduate – Frank Lampard Senior. The former club full-back had been working part-time with the club, scouting and coaching.

His property business was so successful that it cost him financially to return to full-time football as West Ham’s assistant manager. ‘I had a lot of things to consider, but the lure of the job proved too much. If it had been anyone else but Harry and any other club but West Ham I wouldn’t have done it. When I did, I couldn’t wait to get there every morning and get the tracksuit on.’

But, with two Frank Lampards at West Ham, the accusations of nepotism intensified.

Twentieth-century legendary player turned 21st-century newspaper columnist Jimmy Greaves, who began his playing career at Chelsea and ended it at West Ham, wrote about the family connections, to which Harry Redknapp responded, ‘It was a hurtful article. It wasn’t as if I was employing my brother-in-law from the local fish and chip shop. I couldn’t have been luckier than getting Frank to agree to work with me.’

And, being the man he is, Frank Lampard Senior was going out of his way not to do his son any favours. The advice as always: ‘Let your football do the talking.’

His father also explained some facts of footballing fame, ‘I told him that all players have to suffer a bit of abuse at times, even the great Bobby Moore. It’s how you deal with it that’s important. I always found it a little ironic, because young Frank was representing the fans on the pitch. He was claret and blue right through.’

Yet, the envy-hampered doom watchers, those who always believe that the offspring of the famous or the rich or talented will always fall foul of a parent’s shadow, stood back and waited, or offered anonymous jibes from the terraces.

Young Frank wasn’t as thick-skinned then as he would become. He hadn’t the experience. He was soon to get it. It made him grow up quickly. He was lucky. He’d got an excellent education. He’d also got a diploma from the school of hard knocks.