Читать книгу Gerald Durrell - Douglas Botting - Страница 13

FOUR The Garden of the Gods Corfu 1937–1939

ОглавлениеSo the bug-happy boy wandered about his paradise island while conventional education passed him by. For a time Mother endeavoured to stop him turning completely wild by sending him off for daily French lessons with the Belgian Consul, another of Corfu’s great eccentrics. The Consul lived at the top of a tall, rickety building in the centre of the Jewish quarter of Corfu town, an exotic and colourful area of narrow alleys full of open-air stalls, bawling vendors, laden donkeys, clucking hens – and a multitude of stray and starving cats. He was a kindly little man, with gold teeth and a wonderful three-pointed beard, and dressed at all times in formal attire appropriate to his official status, complete with silk cravat, shiny top hat and spats.

Gerald acquired little French from his lessons, but his boredom was alleviated by a curious obsession of his tutor’s. It turned out that the Consul was as compulsive a gunman as Gerald’s brother Leslie, and every so often during the morning lessons he would leap out of his chair, load a powerful air rifle, take careful aim out of the window and blaze away at the street outside. At first Gerald’s hopes were raised by the possibility that the Consul was mixed up in some deadly family feud, though he was puzzled why no one ever fired back, and why, after firing his gun, the Consul would be so upset, muttering dolefully, with tears in his eyes: ‘Ah, ze poor lizzie fellow …’ Finally Gerald discovered that the Consul, a devoted cat lover, was shooting the hungriest and most wretched of the strays. ‘I cannot feed zem all,’ he explained, ‘so I like to make zem happiness by zooting zem. Zey are bezzer so, but iz makes me feel so zad.’ And he would leap up again to take another potshot out of the window.

The Belgian Consul fared no better than any of Gerald’s other hired tutors, totally failing to strike a spark from the boy’s obdurate flint. It was his brother Larry’s educative influence that complemented that of Theo Stephanides, firing him with what he called a ‘sort of verbal tonic’. ‘He has the most extraordinary ability for giving people faith in themselves,’ he was to write of his eldest brother. ‘Throughout my life he has provided me with more enthusiastic encouragement than anyone else, and any success I have achieved is due, in no small measure, to his backing.’ Not long after the family had settled down on Corfu, Lawrence began to take his youngest brother’s literary education in hand. It was under his eclectic but inspired guidance that Gerald was introduced to the world of reading and the basics of writing – above all to the world of Lawrence’s vivid, ever-fermenting imagination.

‘My brother Larry was a kind of god for me,’ Gerald recalled, ‘and therefore I tried to imitate him. Larry had people like Henry Miller staying with him in Corfu and I had access to his very varied library.’ Larry would throw books at him, he remembered, with a brief word about why they were interesting, and if Gerald thought he was right he’d read them. ‘Good heavens, I was omnivorous! I read anything from Darwin to the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover. I adored books by W.H. Hudson, Gilbert White and Bates’ A Naturalist on the River Amazons. I believe that all children should be surrounded by books and animals.’ It was Lawrence who gave his young brother copies of Henri Fabre’s classic works Insect Life: Souvenirs of a Naturalist and The Life and Love of the Insects, with their accounts of wasps, bees, ants, gnats, spiders, scorpions – books which Gerald was later to claim ‘set me off on Corfu’, and which remained an inspiration throughout his life on account of the simplicity and clarity with which they were written and the stimulation they provided the imagination. He was to write:

If someone had presented me with the touchstone that turns everything to gold, I could not have been more delighted. From that moment Fabre became my personal friend. He unravelled the many mysteries that surrounded me and showed me miracles and how they were performed. Through his entrancing prose I became the hunting wasp, the paralysed spider, the cicada, the burly, burnished scarab beetle, and a host of other creatures as well.

Ironically, though, it was a publication that Gerald borrowed from his highly unliterary, gun-slinging brother Leslie that was to sound the clearest call to action for his future life. This was a copy of a popular adventure magazine called Wide World, which serialised a refreshingly humorous account by an American zoologist, Ivan Sanderson, about a recent animal-collecting expedition, led by Percy Sladen, in the wilds of the Cameroons in West Africa. Sanderson’s beguiling tale planted a dream inside Gerald’s young skull, a dream which hardened into a youthful vow of intent that one day he too would combine his love of animals with his yearning for adventure and brave the African wilds in search of rare animals – animals which he would bring back alive, not trapped, shot and stuffed like Percy Sladen’s.

Lawrence’s greatest gift to Gerald was not printed books but language itself, especially language at its most evocative and illuminating, in the form of simile and metaphor. Judging by the progression from Gerald’s earliest literary offerings to those that followed, the impact of his brother’s tuition was electrifying. It was as if Gerald had grown up in a year, emerging by the summer of 1936, when he was eleven, with the perception of someone three times his age. If his next poem, ‘Death’, was not written by Lawrence, the influence of Lawrence totally dominates it, from the subject to the prosody. And the transformation in Gerald’s spelling is suspiciously miraculous.

on a mound a boy lay

as a stream went tinkling by:

mauve irises stood around him as if to

shade him from the eye of death which

was always taking people unawares

and making them till his ground

rhododendrons peeped

at the boy counting sheep

the horror is spread

the boy is dead

BUT DEATH HIMSELF IS NOT SEEN

Lawrence was so impressed by the poem that he sent a copy of it to his friend Henry Miller in America, naming his younger brother as the author. ‘He has written the following poem,’ he wrote. ‘And I am envious.’ Later he included the poem in the November 1937 issue of the Booster, the controversial literary magazine of the American Country Club near Paris, which he edited with Miller, Alfred Pérles and William Saroyan.

By now Mother had found Gerald a new tutor to take the place of George Wilkinson, who had remained at Pérama. He was a twenty-two-year-old friend of Lawrence’s by the name of Pat Evans, ‘a tall, handsome young man,’ Gerald noted, ‘fresh from Oxford.’ Evans entertained serious ambitions of actually educating his young pupil, an aim Gerald himself found ‘rather trying’ and did his best to subvert. He need not have worried, however, for soon the island began to work its languorous magic on the new arrival, and all talk of fractions and adverbs and suchlike was abandoned in favour of a more outdoor kind of teaching, like floating about in the sea while chatting in a desultory way about the effects of warm ocean currents and the origins of coastline geology. Evans had a keen interest in natural history and biology, and he passed on his enthusiasm to his young pupil in a casual, unobtrusive way, ‘walking around, just looking at bugs’, as Margo recalled.

Gerald persuaded Pat Evans to let him write a book as a substitute for English lessons, and soon he was busy scribbling away at a narrative he was to describe as ‘a stirring tale of a voyage round the world capturing animals with my family’, a work Lawrence called ‘his great novel of the flora and fauna of the world’ – a story written very much in the style of the Boy’s Own Paper, with one chapter ending with Mother being attacked by a jaguar and another with Larry caught in the coils of a giant anaconda. Unfortunately, the manuscript was inadvertently left behind in a tin trunk when the family finally left the island, and was probably impounded (so Gerald reckoned) by a bunch of Nazi illiterates during the war and thus lost to posterity for ever.

One fragment of Gerald’s early writing that did survive was a remarkable prose poem, ‘In the Theatre’, which Lawrence also published in the Booster – it was, indeed, Gerald’s first published work. It was clear from ‘In the Theatre’ that Gerald shared with his eldest brother an aptitude for vivid, concrete imagery and the instinct for simile and metaphor which lies at the heart of all poetic vision – much of it drawn from the wildlife the boy had been observing at first hand in his rambles around Corfu.

They brought him in on a stretcher, starched and white, every stitch of it showing hospital work. They slid him on to the cold stone table. He was dressed in pyjamas and jacket, his face looked as if it was carved out of cuttlefish. A student fidgeted, someone coughed, huskily, uneasily. The doctor looked up sharply at the new nurse: she was white as marble, twisting a blue lace handkerchief in her butterfly-like hands.

The scalpel whispered as if it were cutting silk, showing the intestines coiled up neatly like watchsprings. The doctor’s hands moved with the speed of a striking snake, cutting, fastening, probing. At last, a pinkish-grey thing like a sausage came out in the scorpion-like grip of the pincers. Then the sewing-up, the needle burying itself in the soft depth and appearing on the other side of the abyss, drawing the skin together like a magnet. The stretcher groaned at the sudden weight.

When Lawrence first read this prose-poem with his eleven-year-old brother’s name appended to it, he thought it must have been his tutor Pat Evans who had really written it. But Evans denied any involvement. ‘Do you suppose,’ he told Lawrence, ‘that if I could write as well as that I would waste my time on being a tutor?’

But Pat Evans clearly was an inciting agent of some sort in Gerald’s literary development, for later in the year Gerald wrote to Alan Thomas enclosing a copy of his most recent poetic concoction:

I send you my latest opus. Pat and I set each other subjects to write poems in each week. This is my first homewark [sic]. NIGHT-CLUB.

Spoon on, swoon on to death. The mood is blue.

Croon me a stave as sexless as the plants,

Deathless as platinum, cynical as love.

My mood is indigo, my dance is bones.

If there were any limbo it were here.

Dancing dactyls, piston-man and pony

To dewey negroes played by saxophones …

Sodom, swoon on, and wag the deathless boddom.

I love your sagging undertones of snot.

Love shall prevail – and coupling in cloakrooms

When none shall care whether it prevail or not.

Much love to you. Nancy is drawing a bookplate for you. Why? Gerry Durrell

Did the eleven-year-old boy with his simple, innocent passion for blennies and trapdoor spiders really write this unbelievably precocious piece of desperately straining and contrived Weltschmerz? Not only the subject, but the existentialist mind-set, the mood, the vocabulary, the startling and often far-fetched imagery, the compulsive desire to shock, all reek of the influence of Larry the poet, not to mention Larry the uncompromising, anarchic novelist then wrestling with his first major work of fiction, his seriously black – and blue – Black Book. Did Larry actually write it? If not, it can only be seen as a pastiche of Larry, and as such quite stunning for one so young – bizarrely sophisticated nonsense work that nonetheless makes a kind of sense.

A later poem by Gerald entitled ‘An African Dialogue’ was later published, with Lawrence’s help, in a fringe literary periodical called Seven in the summer of 1939. As the final verse indicates, it is remarkable for the cryptic compression of its metaphysical conceit.

She went to the house and lit a candle.

The candle cried: ‘I am being killed.’

The flame: ‘I am killing you.’

The maid answered: ‘It is true, true.

For I see your white blood.’

Meanwhile, family life chez the Durrells was beginning to disintegrate into riot and pandemonium. ‘We’ve got so lax,’ Larry wrote to Alan Thomas, ‘what with Leslie farting at meals, and us nearly naked all day on the point, bathing.’ Nancy agreed. Mother could keep no kind of order at all. ‘Even Gerry could have done better with a little more discipline,’ she complained. ‘I mean he did grow up with really no discipline at all.’ Nancy and Larry were glad of the seclusion and tranquillity of their whitewashed fisherman’s house at Kalami, far from the uproarious family. ‘Ten miles south,’ Larry reported to Thomas, ‘the family brawls and caterwauls and screams in the cavernous new Ypso villa.’

At a cost of £43.1os. the Durrell splinter party had had a top storey added to their house, with a balcony from which they could look over the sea and the hills towards the dying day. For them at least, and later for Gerald and the rest of the family on their forays north, the island entered a new dimension of enchantment.

‘The peace of those evenings on the balcony before the lighting of the lamps was something we shall never discover again,’ Lawrence was to write; ‘the stillness of objects reflected in the mirror of the bay … It was the kind of hush you get in a Chinese water-colour.’ As they sat there, sea and sky merging into a single veil, a shepherd would start playing his flute somewhere under an arbutus out of sight.

Across the bay would slide the smooth, icy notes of the flute; little liquid flourishes, and sleepy squibbles. Sitting on the balcony, wrapped by the airs, we would listen without speaking. Presently the moon appeared – not the white, pulpy spectre of a moon that you see in Egypt – but a Greek moon, friendly, not incalculable or chilling … We walked in our bare feet through the dark rooms, feeling the cool tiles under us, and down on to the rock. In that enormous silence we walked into the water, so as not to splash, and swam out into the silver bar. We didn’t speak because a voice on that water sounded unearthly. We swam till we were tired and then came back to the white rock and wrapped ourselves in towels and ate grapes.

‘This is Homer’s country pure,’ Lawrence scribbled enthusiastically, if not entirely accurately, to Alan Thomas. ‘A few 100 yards from us is where Ulysses landed …’ The diet, he said, was a bit wild. ‘Bread and cheese and Greek champagne … Figs and grapes if they’re in … But in compensation the finest bathing and scenery in the world – and ISLANDS!’

It was inevitable that sooner or later, looking out every day over such an incomparably mesmeric expanse of sea, the family should eventually take to the water. Leslie was the leading spirit in this foray. Before he came to Corfu he had badly wanted to join the Merchant Navy, but his local doctor deemed his constitution wasn’t strong enough. In Corfu he acquired a small boat, the Sea Cow, which he first rowed, then, following the addition of an outboard engine, motored up and down the coast, often alone, sometimes with the rest of the family.

‘You should see us,’ Leslie wrote in one of his infrequent missives home, ‘the whole bloody crowd at sea, it would make you laugh.

One day Larry and Nan came here and I said I would take them home in the boat – Mother, Pat, Gerry, Larry, Nan and myself all in the motor boat. We started off and ran into quite a rough sea. Pat lying on the deck and holding on for all he was worth was dripping in about 5 minutes. Larry, Nan, Mother and Gerry crawled under a blanket – most unseamanlike. The blanket was wet and so was everyone under it. This went on for a bit and things got worse, when suddenly the boat did a beautiful roll and sent gallons of sea water over us. This was enough for Mother and we had to turn back. When Larry, Nan and Pat had had some whiskey and dry clothes they went home in a car.

Sometimes, on dead-still moonlight nights with a glassy sea, Lawrence and Nancy would row across to the Albanian coast for a midnight picnic and then row back, an adventure out of dreamland, pure phantasmagoria. Soon he had bought a boat of his own, a black and brown twenty-two-foot sailing boat called the Van Norden – ‘a dream, my black devil’ – in which they could sail to remoter coasts and islands. Leslie acquired for £3 another small boat, soon to bear the proud name of the Bootle-Bumtrinket, which he and Pat Evans fixed up for Gerald as a birthday present. The boat they produced was, according to Gerald, a genuine oddity in the history of marine construction. The Bootle-Bumtrinket was seven feet long, flat-bottomed and almost circular in shape, painted green and white inside, with black, white and orange stripes outside. Leslie had cut a remarkably long cypress pole for a mast, and proposed raising this at the ceremonial launch and maiden voyage from the jetty in the bay in front of the villa. All did not go according to plan, however, for the moment the mast was inserted in its socket, the Bootle-Bumtrinket – ‘with a speed remarkable for a craft of her circumference,’ Gerald observed – turned turtle, taking Pat Evans with it.

It took a little while for Leslie to redo his calculations, and when he finally sawed the mast down to what he estimated to be the correct length, it turned out to be a mere three feet high, which was insufficient to support a sail. So for the time being the vessel remained a rowing boat, a tub which bobbed upright on the surface of the sea ‘with the placid buoyancy of a celluloid duck’. Gerald made his maiden voyage on a summer’s dawn of perfect calm, with just the faintest breeze. He pushed off from the shore and rowed and drifted down the coast, in and out of the little bays and around the tiny islets of the offshore archipelago, rich in shallow-water marine life. ‘The joy of having a boat of your own!’ he was to remember. ‘There was nothing to compare with that very first voyage.’

Lying side by side with Roger the dog in the bow of the boat as it drifted in towards the shallows, he peered down through a fathom of crystal water at the tapestry of the seabed passing beneath him – the gaping clams stuck upright in the silver sand, the serpulas with their feathery orange-gold and blue petals, ‘like an orchid on a mushroom stem’, the pouting blennies in the holes of the reefs, the anemones waving on the rocks, the scuttling spider-crabs camouflaged with coats of weeds and sponges, the caravans of coloured top shells moving everywhere. Eventually, as the sun sank lower, he began to row for home, his glass jars and collecting tubes full of marine specimens of all kinds. ‘The sun gleamed like a coin behind the olive trees,’ he was to write, ‘and the sea was striped with gold and silver when the Bootle-Bumtrinket brought her round behind bumping gently against the jetty. Hungry, thirsty, tired, with my head buzzing full of the colours and shapes I had seen, I carried my precious specimens slowly up the hill to the villa …’

Sometimes in the summer, if the moon was full, the family went bathing at night, when the sea was cooler than in the heat of the day. They would take the Sea Cow out into deep water and plunge over the side, the water wobbling bright in the moonlight. On one such night, when Gerald had floated out some distance from both shore and boat, he was overtaken by a shoal of porpoises, heaving and sighing, rising and diving all around him. For a short while he swam with them, overjoyed at their beautiful, exuberant presence; but then, as if at a signal, they turned and headed out of the bay towards the distant coast of Albania. ‘I trod water and watched them go,’ he remembered, ‘swimming up the white chain of moonlight, backs aglow as they rose and plunged with heavy ecstasy in the water as warm as fresh milk. Behind them they left a trail of great bubbles that rocked and shone briefly like miniature moons before vanishing under the ripples.’

Soon the family discovered other marvels of the Corfu night – the phosphorescence in the sea and the flickering of the fireflies in the olive groves along the shore, both better seen when there was no moon. On the memorable night that Mother took to the water for the first time in her home-made bathing suit, the porpoises, the fireflies and the phosphorescence coincided in a single breathtaking display. Gerald was to write:

Never had we seen so many fireflies congregated in one spot. They flicked through the trees in swarms, they crawled on the grass, the bushes and the olive trunks, they drifted in swarms over our heads and landed on the rugs, like green embers. Glittering streams of them flew out over the bay, swirling over the water, and then, right on cue, the porpoises appeared, swimming in line into the bay, rocking rhythmically through the water, their backs as if painted with phosphorous … With the fireflies above and the illuminated porpoises below it was a fantastic sight. We could even see the luminous trails beneath the surface where the porpoises swam in fiery patterns across the sandy bottom, and when they leapt high in the air the drops of emerald glowing water flicked from them, and you could not tell if it was phosphorescence or fireflies you were looking at. For an hour or so we watched this pageant, and then slowly the fireflies drifted back inland and further down the coast. Then the porpoises lined up and sped out to sea, leaving a flaming path behind them that flickered and glowed, and then died slowly, like a glowing branch laid across the bay.

The motorboat gave the Durrells a greater freedom to roam round the island than ever before. At first it was Leslie who did the trail-blazing, mainly because of the rich opportunities for hunting and shooting provided by the wilder country to the north. Sometimes he picked up Lawrence and Nancy on the way, since Kalami lay on his passage north from Kondokali. ‘A week or 2. ago,’ Lawrence wrote to Alan Thomas, ‘we went up to a death-swamp lake in the north, Les and Nancy and me for a shoot. Tropical. Huge slime covered tracts, bubbled in hot marsh-gas and the roots of trees. Snakes and tortoises swimming quietly above and toads below. A ring of emerald slime thick with scarlet dragon-flies and mosquitoes. It’s called ANTINIOTISSA (enemy of youth).’

Before long Lawrence had become almost as obsessive a hunter as Leslie. It is extraordinary that Gerald was able to nurture his passion and love for the animal world while his two older brothers seemed hell-bent on blasting the wildlife of the island to pieces. But he did, conniving in the slaughter to the extent of helping to fill Leslie’s cartridges for him and sometimes accompanying him on pigeon shoots, looking on when, out of compassion, Leslie shot the stray and starving dogs that followed the family on their picnics.

Lawrence was largely indifferent to the natural world, except as spectacle, and his expeditions with Leslie to the north of the island revealed a killer streak. ‘I’m queer about shooting,’ he wrote to Alan Thomas. ‘So far I’ve prohibited herons. But duck is a different matter. Just a personified motor-horn, flying ham with a honk. No personality, nothing. And to bring them down is the most glorious feeling. THUD. Like breaking glass balls at a range. I could slaughter hundreds without a qualm.’ As for octopus, which he learned to hunt with a stick with a hook like the Greeks, they were ‘altogether filthy … utterly foul’.

Larry began to revise his opinion of Leslie somewhat after a few shooting trips with him in the north. ‘You wouldn’t recognise Leslie I swear,’ he wrote to Alan Thomas in the summer of 1936. ‘His personality is really amazingly strong now, and he can chatter away in company like Doctor Johnson himself. It’s done him a world of good, strutting about with a gun under each arm and one behind his ear, shooting peasants right and left.’ Leslie saw himself as a tough guy in a tough guy’s world, the fastest gun on the island – ‘dirty, unshaven,’ his kid brother said, ‘and smelling of gun-oil and blood’.

The family had a Kodak camera, and from time to time snapped family groups and memorable outings. Many of the photographs were taken by Leslie, who had an eye for a picture – and a handsome woman. On the back of a snap of Maria, the family’s maid, he jotted a caption full of portent: ‘Maria our maid (jolly nice)’.

Towards the end of the summer of 1936 Mother decided to dispense with the services of Gerald’s tutor, Pat Evans – according to Gerald, on the grounds that he was getting far too fond of Margo, and Margo of him. So departed one of the staunchest supporters of Gerald’s budding natural history and literary endeavours. Banished for ever from the family, the disconsolate Evans found his way to mainland Greece, where during the war he became a local hero, fighting behind the lines as a British SOE agent in Nazi-occupied Macedonia. A rather shy and diffident loner, Evans was, Margo recalled, ‘very, very attractive’, and she had become deeply infatuated with him. She took the news of his dismissal badly, and shut herself away in the attic, eating hugely. ‘This was the period when Margaret was in a very bad way,’ Nancy remembered. ‘She began to get very fat, I mean she really did get awfully fat, and she got so ashamed of herself that she wouldn’t even appear – wouldn’t come down to meals or anything.’ It was neither gluttony nor a broken heart that was the cause of Margo’s weight problem, however, for according to reports it later turned out that she had a glandular condition that was causing her to put on a pound a day.

A new tutor was found, a Polish exile with French and English ancestry by the name of Krajewsky, whom Gerald in his book was to call Kralefsky. A gnome-like humpback, his redeeming virtue, as far as Gerald was concerned, was the huge collection of finches and other birds he kept on the top floor of the mouldering mansion on the edge of town where he lived with his ancient, witch-like mother (‘a ravaged old queen’).

His lessons, however, were old-fashioned and boring – history was lists of dates and geography lists of towns – so it came as a relief to the wearied boy when he discovered that his tutor possessed another virtue. For Krajewsky was a fantasist, and often conjured up an imaginary world in which his past life was presented as a series of wild adventures – a shipwreck on a voyage to Murmansk, an attack by bandits in the Syrian desert, a spot of derring-do in the Secret Service in World War One, an incident in Hyde Park when he strangled a killer bulldog with his bare hands – all of them in the company of ‘a Lady’. Henceforth lessons passed in a more agreeable fashion, with Gerald’s imagination and grasp of story-telling stimulated at the expense of the acquisition of new knowledge.

‘Like everything else in Corfu,’ Gerald was to reflect, ‘it was singularly lucky, this string of outlandish professors who taught me nothing that would be remotely useful in making me conform and succeed and flourish, but who gave me the right kind of wealth, who showed me life.’ And not only life, but freedom, pleasure, the sheer brilliance and sensuality of Corfu.

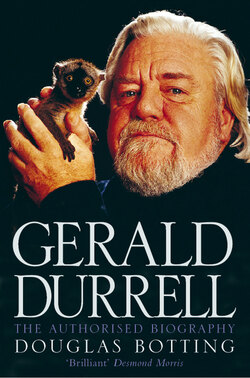

Gerald was growing up. In January 1937 he celebrated his twelfth birthday by throwing a party. To all the guests he sent an invitation in verse, decorated with a self-portrait of himself disguised as a Bacchanalian figure sporting a wild beard and looking uncannily like the man he was to become in later life:

Oh! Hail to you my fellow friends.

Will you yourselves to us lend?

We’re giving a party on 7th of Jan.

Do please come if you possibly can.

The doors are open at half-past three.

Mind you drop in and make whoopee with me.

One of those invited was the Reverend Geoffrey Carr, then Chaplain of the Holy Trinity Church that served the British community living on Corfu, and a good friend of Theo Stephanides and his seven-year-old daughter Alexia.

It was, Carr recalled, a splendid party, with Theo and Spiro and the Belgian Consul and a whole host of Corfu friends in attendance, and Leslie, Theo and the ex-King of Greece’s butler dancing the kalamatianos, and all the pets behaving badly, including the birthday present puppies, who were promptly christened Widdle and Puke, with good reason. A huge home-made cracker, constructed by Margo out of red paper, was suspended from the ceiling. It was eight feet long and three feet in diameter, and was stuffed with confetti, small toys and gifts of food and sweets for the local peasant children (who were sometimes nearly as hungry as the dogs). Disembowelled by Theo using a First World War bayonet belonging to Leslie, the cracker’s demise was the climax of the party, with a scrum of children scrabbling around for the gifts and sweets scattered about all over the floor.

Leslie and Lawrence had already carried out a reconnaissance of Antiniotissa, the large lake at the northern end of the island, and the rest of the family soon followed. The lake was an elongated sheet of shallow water about a mile long, bordered by a dense zariba of cane and reed and closed off from the sea at one end by a broad dune of fine white sand. The best time to visit it was at the season when the sand lilies buried in the dune pushed up their thick green leaves and white blooms, so that the dune became, as Gerald put it, ‘a glacier of flowers’. One warm summer dawn they all set off for Antiniotissa, Theodore and Spiro included, two boatloads full, with the Sea Cow towing the Bootle-Bumtrinket. As the engine died and the boats slid slowly towards the shore, the scent of the lilies wafted out to greet them – ‘a rich, heavy scent that was the distilled essence of summer, a warm sweetness that made you breathe deeply time and again in an effort to retain it within you’.

After establishing their picnic encampment among the lilies on the dune, the family did whatever came naturally to them. Leslie shot. Margo sunbathed. Mother wandered off with a trowel and basket. Spiro – ‘clad only in his underpants and looking like some dark hairy prehistoric man’ – stabbed at fish with his trident. Gerald and Theo pottered among the pools with their test tubes and collecting bottles looking for minuter forms of fauna. ‘What a heavenly place,’ murmured Larry. ‘I should like to lie here for ever. Eventually, of course, over the centuries, by breathing deeply and evenly I should embalm myself with this scent.’ Lunch came, then tea. Gerald and Theo returned to the edge of the lake to continue their search for insufficiently known organisms. Daylight faded as Spiro grilled a fish or an eel on the fire, and before long it grew dark – a still, hushed, magic dark, fireflies rising, fire spitting. This was a special place, Gerald knew, and he absorbed its balm through every sense.

The moon rose above the mountains, turning the lilies to silver except where the flickering flames illuminated them with a flush of pink. The tiny ripples sped over the moonlit sea and breathed with relief as they reached the shore at last. Owls started to chime in the trees, and in the gloomy shadows fireflies gleamed as they flew, their jade-green, misty lights pulsing on and off.

Eventually, yawning and stretching, we carried our things down to the boat. We rowed out to the mouth of the bay, and then in the pause while Leslie fiddled with the engine, we looked back at Antiniotissa. The lilies were like a snow-field under the moon, and the dark backcloth of olives was pricked with the lights of fireflies. The fire we had built, stamped and ground underfoot before we left, glowed like a patch of garnets at the edge of the flowers.

Towards the end of 1937 Mother, Margo, Leslie and Gerald moved to another villa, their third, smaller and handier than the cavernous mansion at Kondokali, but in many ways more desirable and elegant, in spite of its decrepit state. It was a beautiful Georgian house built in 1824 at a spot called Criseda as the weekend retreat, in the days when the British ruled Corfu, of the Governor of the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands. The new house was perched on a hill not so very far from the Strawberry-Pink Villa, and it was dubbed the Snow-White Villa. A broad, vine-covered veranda ran along its front, and beyond lay a tiny, tangled garden, deeply shaded by a great magnolia and a copse of cypress and olive trees. Lawrence and Nancy would sometimes come over for a few days when Kalami became too lonely for them, for as Lawrence put it: ‘You can have a little too much even of Paradise and a little taste of Hell now and then is good for my work – keeps my brain from stagnating. You can trust Gerry to provide the Hell.’

From the back the villa looked out over a great vista of hills and valleys, fields and olive-woods, promising endless days of exploration and a ceaseless quest for creatures great and small – from giant toads and baby magpies to geckoes and mantises. From the front, the villa faced the sea and the long, shallow, almost landlocked lagoon called Lake Halikiopoulou, along whose nearest edge lay the flatlands Gerald was to call the Chessboard Fields. Here the Venetians had dug a network of narrow irrigation canals to channel the salty waters of the lagoon into salt pans, and these ditches now provided a haven for marine life and a protective barrier for nesting birds. On the seaward side of the maze of canals lay the flat sands of the tide’s edge, the haunt of snipe, oyster-catchers, dunlins and terns. On the landward side lay a checkerboard patchwork of small square fields yielding rich crops of grapes, maize, melons and vegetables. All this was Gerald’s hunting ground, where he could roam at will in the orbit of seabird and waterfowl, terrapin and water snake. Here he was to stalk a wily and ancient terrapin he called Old Plop to his heart’s content, and in a roundabout way acquire a favourite pet bird, a black-backed gull called Alecko – Lawrence called it ‘that bloody albatross’ – which he claimed to have got from a convicted murderer on a weekend’s leave from the local gaol.

Gerald was in an ancient rural Arcadia here. There was no airport runway across the lake (unlike today), no busy road at the foot of the hill, no tourist developments, no mini-markets, next to no cars. One old monk still lived alone in the monastery on Mouse Island across the water, and there were still fisher families in the cottages there (now razed). Sometimes Gerald and Margo would go down to the beach at the foot of the hill and swim across the shallow channel to Mouse Island. There Gerald would search for little animals while Margo would sunbathe in her two-piece bathing costume – invariably the old monk would come down and shake his fist at the attractive, pale English girl and yell, ‘You white witch!’ The north European preoccupation with near nudity and sunburn was rather shocking to the devout, straitlaced Greeks.

Not long after Gerald’s thirteenth birthday in January 1938, his idyllic life on Corfu was given a severe jolt when his tutor and mentor Theo Stephanides decided to leave the island to take up an appointment with an anti-malarial unit founded by the Rockefeller Foundation in Cyprus. His departure was to mark the beginning of the end of the Durrell family’s utopian dream.

Leslie had begun to go native, drinking and brawling with the Greek peasant men whenever the opportunity offered. Larry and Nancy had kept themselves busy making improvements to their house in Kalami, but it was not enough. Holed up in the solitude of the north, the young couple had turned upon themselves, rowing vehemently and sometimes violently. It had not helped that in the summer of 1936 Nancy had become pregnant, and had had an abortion arranged by Theo, not something taken lightly in the moral climate of that place and time. Mother had been shocked to the core when she found out about it. The family edifice had begun to crack after that, and Lawrence had started to grow restless and bored in the narrow confines of paradise. When two young English dancers of his acquaintance came to stay, he slept between them on the beach at night, telling Nancy to find somewhere else to sleep. ‘He was going through a stage when he was tired of being an old married man,’ Nancy recalled with bitterness, ‘and so he tried to push me out of it, and snub me all the time, and was being rather beastly.’ Finally Lawrence had decided they should recharge their creative batteries in Paris and London, and leave the island for a while. Margo, now twenty, decided it was time she made her own way in the ‘real world’, and returned to England.

As for Gerald, such childish innocence as he may have brought to the island – not much, doubtless, but some – was blown away with the onset of puberty, when other interests began to conflict with his earlier enthusiasm for non-human forms of life. From time to time he would play ‘mothers and fathers’ with a young female counterpart – an activity that was seen as a natural part of the curiosity of a highly intelligent boy – and in middle age he was to confide to a friend: ‘Before you knew where you were, the knickers were off and you were away.’

Though the remaining Durrells seemed content to drift aimlessly into the future on their paradise island, the world beyond Corfu’s shores had other plans. War was looming in Europe. In the north, Hitler’s Germany was preparing to march. In the south, Mussolini was loudly braying Italy’s claims to dominion over Albania and to territorial rights over Greece, Corfu included.

Lawrence and Leslie had always sworn to help defend the island against the Italians, but they were overtaken by events. By April 1939 Mary Stephanides and her daughter Alexia had already left Corfu to live in England. Gerald was sorry to see the young girl go, for she had become his best and closest playmate. As war in Europe grew more inevitable by the day, Louisa began to think it might be unwise to linger. In My Family Gerald was to claim that it was her concern for his future education that prompted Mother to leave Corfu. By now he was fourteen years old, and was, as Mary Stephanides recalled, ‘quite independent of adult control. Lawrence tried to be a father to him at times, but he was seldom living in the same home, and was in any case too indulgent towards his small brother. And Gerald always got his own way with his mother. Only Theodore maintained any form of control over him, and that was only once a week. So even if war had not started in 1939, the Corfu days of Gerald Durrell were by then strictly numbered.’

It was Grindlays Bank, Mother’s financial advisers in London, who gave the final push, warning her that when war came her funds might be cut off, and she would be stranded in Greece for the duration without any means of support. In June 1939, therefore, she left the island with Gerald, Leslie and the thirty-year-old Corfiot family maid, Maria Condos.

‘As the ship drew across the sea and Corfu sank shimmering into the pearly heat haze on the horizon,’ Gerald was to write of that decisive farewell, ‘a black depression settled on us, which lasted all the way back to England.’ From Brindisi the train bore the party – consisting of four humans, three dogs, two toads, two tortoises, six canaries, four goldfinches, two greenfinches, a linnet, two magpies, a seagull, a pigeon and an owl – northward to Switzerland.

At the Swiss frontier our passports were examined by a disgracefully efficient official. He handed them back to Mother, together with a small slip of paper, bowed unsmilingly, and left us to our gloom. Some moments later Mother glanced at the form the official had filled in, and as she read it, she stiffened.

‘Just look what he’s put,’ she exclaimed indignantly, ‘impertinent man.’

On the little card, in the column headed Description of Passengers had been written, in neat capitals: ONE TRAVELLING CIRCUS AND STAFF.

Now only Lawrence and Nancy were left – or so it seemed – clinging on in the White House on the edge of Kalami bay as the late summer sun burned down on them and the Germans marched into Czechoslovakia and the Italians occupied Albania, only a few miles across the water. But there was one last twist in the family’s Corfu saga, for one day Margo suddenly reappeared, having decided that the island was where her true home and friends were. She holed up in a peasant hut with a tin roof on the Condos family patch at Pérama, sleeping in the same big old wooden bed as her peasant friends Katerina and Renee, washing in a little basin outside the door, and hoping that she could sit out the war on her beloved island disguised as a peasant girl herself.

Lawrence and Nancy lingered a little longer, in some trepidation as to what the future would bring. The confusion of impending war had lapped as far as the north of Corfu now, and it was time to decide whether to go or to be marooned on the island. Margo received a secret note from Spiro, still loyally guarding the family’s interests: ‘Dear Missy Margo, This is to tell you that war has been declared. Don’t tell a soul.’ Lawrence recalled the day war was declared with anguish. ‘Standing on the balcony over the sea,’ he wrote to his friend Anne Ridler in October, ‘it seemed like the end of the world … It was the most mournful period of my life those dark masses murmuring by the lapping water like the Jews in Babylon; such passionate farewells, so many tears, so much language …’

Every able-bodied man and every horse had been mobilised. Corfu town was swarming with people looking for a way to escape, and huge naphtha flares burned on the boats that were unloading bullets and flour at the docks. In Kalami children were weeping in the garden, and Cretan infantry were marching about, ‘smelling like hell, but with great morale’. The local commander was planning to rig up torpedo tubes outside the White House and to mine the straits. Then all the men of the village were sent inland to a secret arms dump, including Anastassiou, ‘our suave, cool, beautiful landlord, too feminine and hysterical to handle a gun’. Only the women were left, weeping around the wells, and the uncomprehending children. ‘I had nothing to say goodbye to except the island,’ Lawrence wrote. ‘I ached for them all.’

Frantically Lawrence and Nancy prepared to leave, destroying papers and drawings, packing the few books they could carry. The little black and brown Van Norden would have to be left behind, and Nancy’s paintings – ‘lazy pleasant paintings of our peasant friends’ that hung on every wall. In weird, autumnal weather, clouds piled high over Albania, the narrow straits like a black sheet, the thin rain falling ‘like Stardust’, they boarded a smoky little Athens-bound steamer at Corfu quay and fled the island. ‘I remembered it all,’ he was to write, ‘with a regret so deep that it did not stir the emotions … We never ever speak of it any more, having escaped.’

Only Margo was left. Before his departure Lawrence had advised her that, should trouble come, she should sail the Van Norden down the Ionian Sea and into the Aegean to Athens – no mean voyage, especially as she had never handled a boat in her life. But she had no fears for her future: ‘I was young, and when you’re young you’re not frightened of anything.’ She had taken to going into Corfu town to hear the news reports and war bulletins relayed to the populace in the Platia, the central square. There, over a coffee or iced drink, she sometimes met up with the Imperial Airways flying-boat crews who were still operating the Mediterranean leg of the Karachi-UK air link. The airmen were aghast at her plan to ride out the war in the Corfu hills, and urged her to leave before the island was invaded and all communications with the outside world were cut. She became friendly with one officer in particular, a dashing young flight engineer by the name of Jack Breeze, and it was he who finally persuaded her to pull out and provided her with the means of doing so. Shortly after Christmas Margo was packed on to one of the last British aircraft flying out of Corfu, and left the island of her young womanhood for ever.

In October 1940 Italian forces entered Greece, and the following year they occupied Corfu. The White House at Kalami lay abandoned, and Larry’s little cutter sunk. Below the Strawberry-Pink Villa, where the boy Gerald had first strode out to explore the wild interior, the Italians built a huge tented camp, where they kept their ration store and marched their soldiers up and down. Later the Germans moved in, strafing the causeway and the chessboard fields of the Venetian lagoon where Gerald had once stalked Old Plop the terrapin, and bombing the old town, killing Theo Stephanides’s parents and Gerald’s tutor Krajewsky and his mad mother and all his birds. What fate befell the boy Gerald’s great manuscript novel of the flora and fauna of the world will never be known.

The Durrell family had been driven from Eden, swept away by the fury and folly of war. All they were left with from their island years were a few crumpled photographs and the memories of a magic life that for long afterwards continued to burn in their minds as vivid and bright as the sun itself.

It was in large part Corfu that made Gerald the person he was to be. But on the island he had known only love and affection, happiness and ease. As a result he was to be ill-equipped for the vicissitudes of real life, which one day would do their best to cut him off at the knees.

Looking back from the hard world beyond the walls of that enchanted garden, Lawrence was to observe many years later: ‘In Corfu, you see, we reconstituted the Indian period which we all missed. The island exploded into another open-air time of our lives, because one lived virtually naked in the sun. Without Corfu I don’t think Gerry would have managed to drag himself together and do all he has achieved … I reckon I too got born in Corfu. It was really the spell between the wars that was – you can only say paradise.’