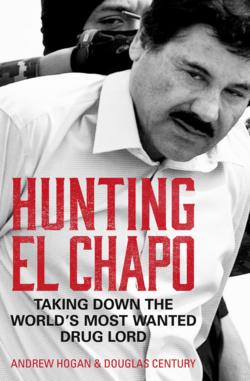

Читать книгу Hunting El Chapo: Taking down the world’s most-wanted drug-lord - Douglas Century, Andrew Hogan - Страница 11

ОглавлениеBREAKOUT

GUADALAJARA, MEXICO

May 24, 1993

THE SUDDEN BURST OF AK-47 gunfire pierced the calm of a perfect spring afternoon, unleashing panic in the parking lot of the Guadalajara Airport. Seated in the passenger seat of his white Grand Marquis, Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, the Archbishop of Guadalajara, was struck fourteen times as he arrived to meet the flight of the papal nuncio. The sixty-six-year-old cardinal slumped toward the center of the vehicle, blood running down his forehead. He had died instantly. The Grand Marquis was riddled with more than thirty bullets, and his driver was among six others dead.

Who would possibly target the archbishop—one of Mexico’s most beloved Catholic leaders—for a brazen daylight hit? The truth appeared to be altogether more prosaic: it was reported that Cardinal Posadas had been caught up in a shooting war between the Sinaloa and Tijuana cartels, feuding for months over the lucrative “plaza”—drug smuggling route—into Southern California. Posadas had been mistaken for the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán Loera, a.k.a. “El Chapo,” who was due to arrive at the airport parking lot in a similar white sedan at around the same time.

News footage of the Wild West–style shoot-out flashed instantly around the world as authorities and journalists scrambled to make sense of the carnage. “Helicopters buzzed overhead as police confiscated about 20 bullet-riddled automobiles, including one that contained grenades and high-powered automatic weapons,” reported the Los Angeles Times on its front page. The daylight assassination of Cardinal Posadas rocked Mexican society to its core; President Carlos Salinas de Gortari arrived immediately to pay his condolences and calm the nation’s nerves.

The airport shoot-out would prove to be a turning point in modern Latin American history: for the first time, the Mexican public truly took note of the savage nature of the nation’s drug cartels. Most Mexicans had never heard of the diminutive Sinaloa capo whose alias made him sound more comical than lethal.

After Posada’s assassination, crude drawings of Chapo’s face were splashed on front pages of newspapers and magazines all across Latin America. His name appeared on TV nightly—wanted for murder and drug trafficking.

Realizing he was no longer safe even in his native Sierra Madre backcountry, or in the neighboring state of Durango, Guzmán reportedly fled to Jalisco, where he owned a ranch, then to a hotel in Mexico City, where he met with several Sinaloa Cartel lieutenants, handing over tens of millions in US currency to provide for his family while he was on the lam.

In disguise, using a passport with the name Jorge Ramos Pérez, Chapo traveled to the south of Mexico and crossed the border into Guatemala on June 4, 1993. His plan apparently was to move stealthily, with his girlfriend and several bodyguards, then settle in El Salvador until the heat died down. It was later reported that Chapo had paid handsomely for his escape, bribing one Guatemalan military officer with $1.2 million to guarantee his safe passage south of the Mexican border.

IN MAY 1993, around the time of the Posada murder, I was fifteen hundred miles away, in my hometown of Pattonville, Kansas, diagramming an intricate pass play to my younger brother. We were Sweetness and the Punky QB—complete with regulation blue-and-orange Bears jerseys—huddling up in the front yard against a team made up of my cousins and neighbors. My sister and her friends were dressed up as cheerleaders, with homemade pompoms, shouting from the sidelines.

My brother, Brandt, always played the Walter Payton role. I was Jim McMahon, and I was a fanatic—everyone teased me about it. Even for front-yard games, I’d have to have all the details just right, down to the white headband with the name ROZELLE, which I’d lettered with a black Magic Marker, just like the one McMahon had worn in the run-up to the 1985 Super Bowl.

None of us weighed more than a hundred pounds, but we took those front- yard games seriously, as if we really were Payton, McMahon, Singletary, Dent, and the rest of the Monsters of the Midway. In Pattonville—a town of three thousand people, fifty-two miles outside Kansas City—there wasn’t much else to do besides play football and hunt. My father was a firefighter and lifelong waterfowl hunter. He’d taken me on my first duck hunt at age eight and bought me my first shotgun—a Remington 870 youth model—when I turned ten.

Everyone expected I’d become a firefighter, too—my greatgrandfather, my grandfather, and three uncles had all been firemen. I’d spend hours at the fire station following my dad around, trying on his soot-stained leather fire helmet and climbing in and out of the trucks in the bay. In fifth grade, I brought home a school paper and showed my mom:

“Someday I’m going to be . . . a fireman, a policeman, or a spy detective.”

But as long as I could remember, I’d really been dead set on becoming one thing: a cop. And not just any cop—a Kansas State Trooper.

I loved the State Troopers’ crisp French-blue uniforms and navy felt campaign hats, and the powerful Chevrolets they got to drive. For years I had an obsession with drawing police cars. It wasn’t just a hobby, either—I’d sit alone in my bedroom, working in a feverish state. I had to have all the correct colored pens and markers lined up, drawing and shading the patrol cars in precise detail: correct light bar, insignia, markings, wheels—the whole works had to be spot-on, down to the exact radio antennas. I’d have to start over even if the slightest detail looked off. I drew Ford Crown Vics and Explorers, but my favorite was the Chevy Caprice with the Corvette LT1 engine and blacked- out wheels. I’d often dream while coloring, picturing myself behind the wheel of a roaring Caprice, barreling down US Route 36 in hot pursuit of a robbery suspect...

Fall was my favorite time of year. Duck hunting with my dad and brother. And football. Those front-yard dreams now playing out under the bright stadium lights. Our varsity team would spend Thursday nights in a barn or some backwoods campsite, sitting around a fire and listening to that week’s motivational speaker, everyone’s orange helmets, with the black tiger paws on the sides, glowing in the flickering light.

Life in Pattonville revolved around those Friday-night games. All along the town’s roads you’d see orange-and-black banners, and everyone would come and watch the Tigers play. I had my own pregame ritual, blasting a dose of Metallica in my headphones:

Hush little baby, don’t say a word And never mind that noise you heard

After high school, I was convinced that I’d live in the same town where my parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and dozens of cousins lived. I had no desire to go anyplace else. I never could have imagined leaving Pattonville. I never could have imagined a life in a smog- cloaked city of more than 26 million, built on top of the ancient Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán...

Mexico? If pressed—under the impatient glare of my thirdperiod Spanish teacher—I probably could have found it on the map. But it might as well have been Madagascar.

I WAS SOON THE black sheep: the only cop in a family of firefighters. After graduating from Kansas State University with a degree in criminal justice, I’d taken the written exam for the Kansas Highway Patrol, but a statewide hiring freeze forced me in another direction. A salty old captain from the local sheriff ’s office offered me a job as a patrol deputy with Lincoln County, opening my first door to law enforcement.

It wasn’t my dream job, but it was my dream ride: I was assigned a 1995 Chevrolet Caprice, complete with that powerhouse Corvette engine—the same squad car I’d been drawing and coloring in detail in my bedroom since I was ten years old. Now I got to take it home and park it overnight in the family driveway.

Every twelve-hour shift, I was assigned a sprawling twenty-by thirty-mile zone. I had no patrol-car partner: I was just one babyfaced deputy covering a vast countryside scattered with farmhouses and a few towns. The closest deputy would be in his or her zone, just as large as mine. If we were on the opposite ends of our respective zones and needed backup, it could take thirty minutes to reach each other.

I discovered what that really meant one winter evening during my rookie year when I went to look for a six-foot-four, 260-pound suspect—name of “Beck”—who’d just gotten out of the Osawatomie State Hospital psychiatric ward. I’d dealt with Beck once already that night, after he’d been involved in a domestic disturbance in a nearby town. Just after 8 p.m., my in-car mobile data terminal beeped with a message from my sergeant: “Hogan, you’ve got two options: get him out of the county or take him to jail.”

I knew I was on my own—the sergeant and other deputies were all handling a vehicle in the river, which meant my colleagues were twenty minutes away at a minimum. As I drove down a rural gravel road, in my headlights I caught a dark figure ambling on the shoulder. I let out a loud exhale, pulling to a stop.

Beck.

Whenever I had a feeling that things were going to get physical, I tended to leave my brown felt Stratton hat on the passenger seat. This was one of those times.

“David twenty-five,” I radioed to dispatch. “I’m going to need another car.”

It was the calmest way of requesting immediate backup. But I knew the truth: there wasn’t another deputy within a twenty-five mile radius.

“The Lone fuckin’ Ranger,” I muttered under my breath, stepping out of the Caprice. I walked toward Beck cautiously, but he continued walking away, taking me farther and farther from my squad car’s headlights, and deeper and deeper into the darkness.

“Sir, I can give you a ride up to the next gas station or you can go to jail,” I said, as matter-of-factly as I could. “Your choice tonight.”

Beck ignored my question completely, instead picking up his pace. I half jogged, closed the distance, and quickly grabbed him around his thick bicep to put him in an arm bar. Textbook—just how I’d been taught at the academy.

But Beck was too strong to hold, and he lunged forward, trying to free his arm. I felt the icy gravel grinding beneath us as we both tried to gain footing. Beck snatched me in a bear hug, and there were quick puffs of breath in the cold night air as we locked eyes for a split second, faces separated by inches. I had zero leverage—my feet now just barely touched the ground. It was clear that Beck was setting up to body- slam me.

I knew there was no way I could outgrapple him, but I managed to rip my right arm loose and slammed my fist into his pockmarked face, then again, until a third clean right sent Beck’s head snapping back and he finally loosened his grip. I planted my feet to charge, as if I were going to make a football tackle, and rammed my shoulder into Beck’s gut, driving him to the ground. Down into the steep frozen ditch we barrel-rolled on top of each other, Beck trying to grab for my .45-caliber Smith & Wesson pistol, unclasping the holster snaps, nearly getting the gun free.

I finally got the mount, reached for my belt, and filled Beck’s mouth and eyes with a heavy dose of pepper spray. He howled, clutching at his throat, and I managed to get him handcuffed, on his feet, and into the backseat of the Caprice. We were halfway to the county jail before my closest backup even had a chance to respond. It was the scariest moment of my life—until twelve years later, when I set foot in Culiacán, the notorious capital of the Mexican drug underworld....

DESPITE THE DANGERS, I quickly developed a taste for the hunt. During traffic stops, I’d dig underneath seats and rummage through glove compartments in search of drugs, typically finding only halfempty nickel bags of weed and crack pipes. Then, one evening on a quiet strip of highway, I stopped a Jeep Cherokee for speeding. The vehicle sported a small Grateful Dead sticker in the rear window, and the driver was a forty-two-year-old hippie with a greasestained white T-shirt. I knew exactly how to play this: I acted like a clueless young hillbilly cop, obtained his verbal consent to search the Jeep, and discovered three ounces of rock cocaine and a bundle of more than $13,000 in cash.

The bust made the local newspapers—it was one of the largest drug-cash seizures in the history of our county. I soon got a reputation for being a savvy and streetwise patrolman, skilled at sniffing out dope. It was a natural stepping-stone, I was sure, to reaching my goal of becoming a Kansas State Trooper.

But then a thin white envelope was waiting for me when I drove the Caprice home one night after my shift. The Highway Patrol headquarters, in Topeka, had made its final decision: despite passing the exam, I was one of more than three thousand applicants, and my number simply was never drawn.

I called my mom first to let her know about the rejection. My entire family had been waiting weeks to hear the exam results. The moment I hung up the phone, my eyes fixed on the framed photo of the Kansas Highway Patrol patch I’d had since college. I felt the walls of my bedroom closing in on me—as tight as the corridor of the county jail. Rage rising into my throat, I turned and smashed the frame against the wall, scattering the glass across the floor. Then I jumped onto my silver 2001 Harley-Davidson Softail Deuce and lost myself for five silent hours on the back roads, stopping at every dive bar along the way.

My dad was now retired from the Pattonville Fire Department and had bought the town’s original firehouse—a two-story redbrick 1929 building on the corner of East Main and Parks Street—renovated it, and converted it into a pub. Pattonville’s Firehouse Pub quickly became the town’s busiest watering hole, famous for its hot wings, live bands, and raucous happy hours.

The pub was packed that night, a four-piece band playing onstage, when I pulled up outside the bar and met up with my old high school football buddy Fred Jenkins, now a Kansas City firefighter.

I tried to shake it off, but my anger kept simmering—another bottle of Budweiser wasn’t going to calm this black mood. I leaned over and yelled at Freddie.

“Follow me.”

I led him around to the back of the pub.

“What the hell you doing, man?”

“Just help me push the fuckin’ bike in.”

Freddie grabbed hold of the front forks and began to push while I backed my Deuce through the rear door of the bar.

I saddled up and ripped the throttle, and within seconds white smoke was billowing around the rear tire as it cut into the unfinished concrete floor.

A deafening roar—I had the loudest pipes in town—quickly drowned out the sound of the band. Thick, acrid-smelling clouds filled the bar as I held on tight to the handlebars, the backs of my legs pinched against the rear foot pegs to keep the hog steady—the ultimate burnout—then I screeched off, feeling only a slight relief.

I parked the Deuce and walked back into the bar, expecting high fives—something to lighten my mood—but everyone was pissed, especially my father.

Then some old retired fireman knocked me hard on the shoulder.

“Kid, that was some cool shit,” he said, “but now my chicken wings taste like rubber.”

I reached into my jeans and pulled out a wad of cash for a bunch of dinners. Then I saw my father fast approaching behind the bar.

“Let’s roll,” I yelled through the crowd to Freddie. “Gotta get outta here before my old man beats my ass.”

I RETESTED WITH the Highway Patrol but started looking into federal law enforcement careers, too—one of my best cop buddies had told me good things about the Drug Enforcement Administration. Until then, I had never considered a career as a special agent, but I decided to take the long drive over to Chicago and attend their orientation. The process was surprisingly quick, and I was immediately categorized as “best qualified,” with my past police experience and university degree. Months went by without a word, but I knew it could take more than a year before I completed the testing process. One fall morning, I was back on my Harley with a bunch of cops and firefighters for the annual US Marine Corps Toys for Tots fund-raising ride. After a long day cruising the back roads, doing a little barhopping, I let slip to Freddie’s cousin, Tom, that I had applied with the DEA.

“No kidding? You know Snake?” Tom said, then called across the bar: “Snake! Get over here—this kid’s applying with the DEA.” Snake swaggered over in his scuffed-up leather jacket. Headful of greasy blond shoulder-length hair, wearing a half- shaven beard and a scowl, he looked more like a full-patch outlaw biker than a DEA agent.

I hit it off with Snake right away—we downed a couple of bottles of Bud and talked about the snail-paced application process.

“Look, kid, it’s a pain in the ass, I know—here’s my card,” Snake said, giving me his number. “Call me Monday.”

Before I knew it, thanks to Snake, I found myself on a fast track through the testing process and received an invitation to the DEA Training Academy. One last blowout night at the Firehouse Pub, then I headed east, breaking free of my meticulously laidout life in Kansas. I drove through the heavily forested grounds at Quantico—chock-full of whitetail deer so tame you could practically pet them—and entered the gates of the DEA Academy as a member of a brand-new class of basic agent trainees.

I had barely settled into life at Quantico when I got a call telling me I’d been selected as a candidate for the next Kansas Highway Patrol class. I scarcely believed what I heard myself telling the master sergeant on the phone.

“Thanks for the invite,” I said, “but I’m not leaving DEA.” By that point, I was throwing myself headlong into the DEA training.

We spent hours on the range, burning through thousands of rounds of ammunition, firing our Glock 22 .40-caliber pistols or busting our asses doing PT out near the lake’s edge—sets of burpees in the icy, muddy water, followed by knuckle push- ups on the adjacent gravel road.

The heart of academy training was the practical scenarios. We called them “practicals.” One afternoon during a practical, I had the “eye” on a target—an academy staff member playing the role of a drug dealer—planning an exchange with another bad guy in a remote parking lot. I parked just out of sight, grabbed my binoculars and radio, and crawled up underneath a group of pine trees.

“Trunk is open,” I radioed my teammates. “Target One just placed a large black duffel bag into the back of Target Two’s vehicle. They’re getting ready to depart. Stand by.”

Alone in my Ford Focus, I followed the second target vehicle to another set.

Time for the vehicle-extraction takedown. I still had eyes on Target Two, but none of my teammates had arrived in the parking lot. Minutes passed; I was staring at my watch, calling my team on the radio; I knew we needed to arrest the suspect now or we’d all flunk the practical.

I hit the gas and came to a skidding stop near the rear of the target vehicle, and, with my gun drawn, I rushed the driver’s door.

“Police! Show me your hands! Show me your hands!”

The role player was so startled he didn’t even react. I reached in through the door and grabbed him by the head—hauling him from the vehicle and throwing him face-first onto the asphalt before cuffing him.

My team passed the practical, but I caught pure hell from our instructor during the debrief. “Think you’re some kind of goddamn cowboy, Hogan? Why didn’t you wait for your teammates before initiating the arrest?”

Wait?

I held my tongue. It wasn’t that easy to unwire the aggression, the street-cop instinct, honed during those years working alone as a deputy sheriff with no backup.

That tag—Cowboy—stuck with me for the final weeks of the academy.

I graduated in the top of my class and, with my whole family present, walked across the stage in a freshly pressed dark blue suit and tie to receive my gold badge from DEA Administrator Karen Tandy, then turned and shook the hand of Deputy Administrator Michele Leonhart.

“Congratulations,” Michele said. “Remember, go out there and make big cases.”

THE PRISON WAS his playground.

Down in Jalisco—the home of Mexico’s billion-dollar tequila industry—Chapo was living like a little prince. On June 9, 1993, after successfully slipping into Guatemala, he was apprehended by the Guatemalan army at a hotel just across the border. The political heat was too intense: he couldn’t bribe his way out of this jam. It was the first time his hands had felt the cold steel of handcuffs, and his first police mug shot was taken in a puffy tan prison coat. Before long, Guzmán was aboard a military plane, taken to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1, known simply as Altiplano, the maximum-security prison sixty miles outside Mexico’s capital.

By now the public knew more about Chapo. The young campesino had dropped out of school and sold oranges on the streets to help support his family. Later he’d been a chauffeur—and allegedly a prodigious hit man—for Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, a.k.a. “El Padrino,” the godfather of modern Mexican drug trafficking.

Born on the outskirts of Culiacán, Gallardo had been a motorcycleriding Mexican Federal Judicial Police agent and a bodyguard for the governor of Sinaloa, whose political connections Gallardo used to help build his drug-trafficking organization (DTO). A business major in university, Gallardo had seen a criminal vision of the future: he united all the bickering traffickers—mostly from Sinaloa—into the first sophisticated Mexican DTO, called the Guadalajara Cartel, which would become the blueprint for all future Mexican drugtrafficking organizations.

Like Lucky Luciano at the birth of modern American organized crime, in the late 1920s, Gallardo recognized that disputed territory led to bloodshed, so he divided the nation into smuggling “plazas” and entrusted his protégé, Chapo Guzmán, with control of the lucrative Sinaloa drug trade.

While he was behind bars after his Guatemalan capture, Guzmán’s drug empire continued to thrive. Chapo’s brother, Arturo, was the acting boss, but Chapo himself was still clearly calling all the shots—he was now ranked as the most powerful international drug trafficker by authorities in both Mexico and the United States.

Chapo was moving staggering amounts of cocaine—regularly and reliably—from South America up through Central America and Mexico and into the United States. These weren’t small-time muling jobs, either: Chapo’s people were moving multi-ton shipments of Colombian product via boat, small planes, even jerry-rigged “narco subs”—semi-submersible submarines capable of carrying six tons of pure cocaine at a time. Chapo’s methods of transport were creative—not to mention constantly evolving— and he thereby earned a reputation for getting his loads delivered intact and on time. Chapo expanded his grip to ports on Mexico’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts and strong-armed control of key crossing points—not just on the US-Mexico border but also along Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala.

Chapo embedded lieutenants of the Sinaloa Cartel in Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Venezuela, giving him more flexibility to negotiate directly with traffickers within the supply chain. His criminal tentacles, versatility, and ingenuity surpassed even his more infamous predecessors, like Pablo Escobar. Headline-making seizures of Chapo’s cocaine—13,000 kilograms on a fishing boat, 1,000 on a semi-submersible, 19,000 from another maritime vessel en route to Mexico from Colombia—were mere drops in the cartel’s bucket, losses chalked up to the cost of doing business.

Even from behind bars, Chapo had the insight to diversify the Sinaloa Cartel’s operations: where it had previously dealt strictly in cocaine, marijuana, and heroin, the cartel now expanded to the manufacture and smuggling of high-grade methamphetamine, importing the precursor chemicals from Africa, China, and India.

On November 22, 1995—and after being convicted of possession of firearms and drug trafficking and receiving a sentence of twenty years—Chapo arranged to have himself transferred from Altiplano to the maximum-security Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 2, known as Puente Grande, just outside Guadalajara.

Inside Puente Grande, Guzmán quickly built a trusted relationship with “El Licenciado”—or simply “El Lic”—a fellow Sinaloan, from the town of El Dorado. El Lic had been a police officer at the Sinaloa Attorney General’s Office before being appointed to a management position in Puente Grande prison.

Under El Lic’s watch, Chapo reportedly led a life of luxury—liquor and parties, and watching his beloved fútbol matches. He was able to order special meals from a handpicked menu, and when that grew boring, there was plenty of sex. Chapo was granted regular conjugal visits with his wife, various girlfriends, and a stream of prostitutes. He even arranged to have a young woman who was serving time for armed robbery transferred to Puente Grande to further tend to his sexual needs. The woman later revealed Chapo’s supposed romantic streak: “After the first time, Chapo sent to my cell a bouquet of flowers and a bottle of whiskey. I was his queen.” But the reality was more tawdry: on the nights he got bored with her, it was said he passed her off among other incarcerated cartel lieutenants.

It was clear that Chapo was the true boss of the lockup. With growing fears of being extradited to the United States, he planned a brazen escape from Puente Grande.

And sure enough, just after 10 a.m. on January 19, 2001, Guzmán’s electronically secured cell door opened. Lore has it that he was smuggled out in a burlap sack hidden in a laundry cart, then driven through the front gates in a van by one of the corrupt prison guards in a mode reminiscent of John Dillinger’s famous jailbreaks of the 1930s.

The escape required complicity, cooperation, and bribes to various high-ranking prison officials, police, and government authorities, costing the drug lord an estimated $2.5 million. At 11:35 p.m., the prison warden was notified that Chapo’s cell was empty, and chaos ensued. When news of his breakout hit the press, the Mexican government launched an unprecedented dragnet, the most extensive military manhunt the country had mounted since the era of Pancho Villa.

In Guadalajara, Mexican cops raided the house of one of Guzmán’s associates, confiscating automatic weapons, drugs, phones, computers, and thousands of dollars in cash. Within days of the escape, though, it was clear that Guzmán was no longer in Jalisco. The manhunt spread, with hundreds of police officers and soldiers searching the major cities and sleepiest rural communities.

Guzmán called a meeting of all the Sinaloa Cartel lieutenants, eager to prove that he was still the top dog. A new narcocorrido swept the nation, “El Regreso del Chapo.”

No hay Chapo que no sea bravo Así lo dice el refrán2

Chapo was not just bravo: he was now seen as untouchable—the narco boss that no prison could hold. Sightings were reported the length of the nation, but whenever the authorities were getting close to a capture, he could quickly vanish back into his secure redoubt in the Sierra Madre—often spending nights at the ranch where he’d been born—or back into the dense forests and marijuana fields. He was free, flaunting his power, and still running the Sinaloa Cartel with impunity.

It would be nearly thirteen years before he again came face-to-face with any honest agent of the law.