Читать книгу Nine Parts Water, One Part Sand - Douglas Galbraith - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBeechworth, North East Victoria. When I was growing up, the town was all county football, bad beer and public service institutions — the gaol, the aged care home, and the psych hospital. Music was strictly square, the outside world unknown.

One weekend, at age 16, I took a pilgrimage to Melbourne, 300 kilometres away. Sitting on the shabby carpet of my sister’s Camberwell rental house, an epiphany in the shape of her wannabe-punk boyfriend’s record collection shone out of the suburban night. I scrambled frantically through the vinyl — Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. Radio Birdman, the Stooges, the Cramps, the Ramones. Intoxica, Cosmic Pyschos, Corpse Grinders and X. It was an epiphany, as though a new universe had been revealed. I was in awe.

In amongst all this gold, was Kim Salmon. Scientists, the Surrealists, and the Beasts of Bourbon. Sinister looking albums — a dark, blood red theatre with the band lying indolently amongst the empty seats; a ghostly monochromed half-impression of the band with the suggestion that there was much, much more to see.

On one album, ‘The Axeman’s Jazz’, the gang of miscreant Beasts slunk back in the darkness, glowering, looking like cats you’d want to know, but not get on the wrong side of. The vinyl quickly found its way onto the turntable. Mumbled studio chatter and a faint count in gives way to guitars, scratchy, lackadaisical rhythm and demented cowboy licks that thread their way throughout the song. From the very first sounds, I was sold.

•••

It’s a Sunday afternoon in Brunswick Street Fitzroy when, still underage, I walk into the front bar of the Punters Club Hotel. The sunlight quickly loses penetration in the comfortably shadowy bar, where the barkeeper is immersed in cleaning beer glasses.

I’m still green, and mistakenly think Kim’s surname is pronounced SALmon with a hard L. I say to the taciturn barman, ‘is Kim SAL-mon playing here?’ He barely looks up as he sneers with contempt, ‘It’s Salmon’.

I am chastened and retreat, but see a poster saying, ‘Kim Salmon Solo Residency’. And there, in the band room, is Kim Salmon with his Fender Thinline and a huge can of European beer. Kim tilts to the side with left leg stuck out slightly off kilter as he leans into the microphone. His shirt is a stranger to its buttons, and his sharp boot taps out the song’s heartbeat as he conjures its body from the guitar. There’s only one of him, but the Punters sounds like it’s hosting a band as the bass notes run their own lines, joining the melody which lurks somewhere above.

‘The unknown remains unknowable, until you finally know it. The un-thought remains unthinkable, until you happen to think it,’ he intones. ‘And the obvious is always obvious, except of course, when it isn’t … obvious’. These intriguing word plays hold the audience hushed, and the heavy musical mood draws us into the murky landscapes.

I purchase the cassette Hook Line and Singer with a hand drawn Kim Salmon on the cover and listen to it relentlessly. The songs on the tape, and from that Sunday afternoon gig, remain just as potent today.

•••

The night before we’d seen Fugazi & Magic Dirt and tonight here we are standing on the hallowed turf of the MCG. The biggest band in the world, U2, are posturing on stage, all sunglasses and leather pants and beanies and TV screens. Earlier, Kim Salmon and the Surrealists had delivered a blistering opening set, Salmon screaming ‘I declare myself a GOD’ to the assembled U2 fans as the sun faded over the colosseum.

How many of the 50,000 crowd had come to watch the opening, rather than the main, act? Maybe just us … Standing on a seat in the midst of the screaming crowd, I scan the scene gazing slowly from left to right. And there, standing only meters away, alone and contemplative in a yellow velvet jacket, is Kim Salmon. ‘50,000 people’, I think, ‘and he stands next to us. It’s gotta be fate …’

•••

Many years later, I see Kim at the IGA Supermarket on Station Street, Fairfield. How odd to see the Godfather of Grunge doing such a mundane thing as buying groceries — and at my local!

Then, I read an article in the Age, a journo relating a tale of guitar lessons with Kim. Wouldn’t that be cool …1

So, late at night, a bottle of wine directing traffic, I hit send on the email link to the Salmon webpage. ‘Do you still do private guitar lessons …?’ The next day, Kim Salmon replied, ‘Sure. How about Wednesdays?’

And so, every Wednesday evening I decamped to the front room of Kim’s house, my Epiphone Hummingbird sounding like an imposter amongst the Fenders and Col Clarkes. We played — he taught, I learnt.

And always, we talked. An idea grew and itched and refused to go away. Until one night at 2:27am, I hit send on this email:

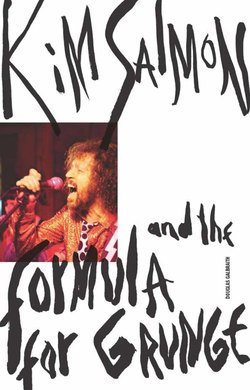

‘Hey Kim. An idea to run by you, triggered by some comments you’ve made, a gap in the market and a bottle of Sangiovese. When I started lessons with you I did a search for a biography and couldn’t find one. I thought that was outrageous and a missing part of Australian music history. So, I wanted to let you know that in the unlikely event you wanted an untried unknown non author to write your book, then I’d jump at the chance. No harm asking right?’

Kim’s reply was positive but guarded, concluding ‘Let me think about it.’ Next week at our guitar lesson, I was more nervous than usual. I played badly and felt the weight of this question about the book hanging between us. Finally, as I packed up my guitar, almost red with the embarrassment of not talking about it, Kim switched off his amp and said casually, ‘So, you written my book yet?’

•••

The book starts with breakfast. I arrive first, awash with nerves. I stare at the menu from which endless breakfast options cascade in a torrent. Kim Salmon walks in, sits down and promptly orders fruit toast and a long black with milk on the side. Already three coffees in, I follow with a strong flat white and in a train wreck of cognition, order waffles. What arrives is a monolithic tower of berries, cream cheese, waffles and sugar. It’s an abomination, a screeching banshee soaking up the oxygen, an aberration next to the understated fruit toast sitting calmly on the small plate. ‘Wow,’ observes Salmon. ‘You win. That’s not breakfast, that’s dessert.’

We start talking, and this is how it goes — a crooked pathway back and forth through Kim’s life, journeys through songs, bands, artists, movies, politics, clothes, hair, people and places. We talk at great length on small fragments of life. Breakfasts turn into lists, phone numbers, emails and before long, I’m on a plane.

I land in Perth. It’s like a foreign city — sunny, calm and at ease. I drive up Wade Street where the swamps have given way to housing but still look untamed, holding the echo of a young Kim Salmon riding his bike and catching gilgees. Kim’s mother, Joy, is sitting on the step of the house at the end of a long driveway to meet me. She is small, sharp and instantly welcoming. We step inside. This was the house where a teenage Kim Salmon would soak up valuable bathroom time, practicing rock moves in front of the mirror and tweaking his hair. Joy introduces me to Kim’s father, Owen. He is neat, upright — a proud man with a firm handshake.

Joy makes coffee before we retire to the lounge room, and I set up the Zoom recorder on the carpet.