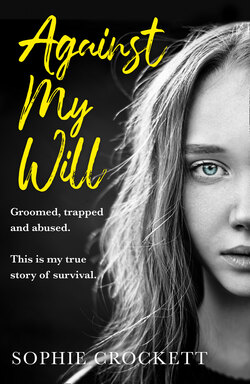

Читать книгу Against My Will - Douglas Wight - Страница 12

Chapter 4

ОглавлениеIt looked harmless enough. Fun, even. And I hadn’t exactly enjoyed many fun times before we paid a trip to Brecon. I was with my parents and sister, and my primary reason for going there was to visit a bookshop. On the opposite side of the street was a spiritual crystal shop hosting a fair for all kinds of psychic practices. My kind of place, surely?

Once we went inside I saw that a psychic artist, who I will call Phil, was offering readings through art.

‘I’d like to get this,’ I said.

My parents shrugged and said it was fine, if that was what I wanted. Phil seemed perfectly nice and showed me upstairs to a small room where he did his artwork, while my family waited downstairs. He talked quietly and asked me some questions to get a sense of who I was so he could tune in and contact my spirit guide. He asked for some personal information, my name and phone number. I gave these to him without thinking much of it. Phil then explained that he would tune in to my spirit and channel it through his artwork.

I sat there, quite intrigued. He was sketching the figure of a man, but with large wings. As he was drawing he edged closer and closer towards me. I felt uncomfortable so I got up. He stood up too and I backed against the wall. He moved right in front of me, his large frame blocking the stairs. I started to feel scared. He was so close I could feel his breath on my face. He put his hand against the wall next to my head.

‘You’re a very special girl, Sophie,’ he said, pinning me against the wall.

I didn’t know what was going on. But I knew this wasn’t right. Before he could do or say anything else, I slipped under his arm and ran down the stairs. My parents were still there, waiting for me.

‘What’s wrong?’ my dad said, seeing the look on my face.

‘I don’t know,’ I said, truthfully. I really didn’t know what had just happened.

I looked back up the stairs and Phil was there holding the drawing. ‘Sophie, you forgot your picture,’ he said.

He came down casually behind me, smiling as if nothing had happened. He chatted to my dad a little bit about mundane things and said everything went well. All the time I just wanted to get away.

On the journey home my parents could sense something was wrong. They kept asking me what, but I just replied, ‘I don’t know.’

Back at the house I looked at his half-drawn picture to see what meaning I could glean from it. Not much. A short while later my phone buzzed with a message. It was Phil. He asked how I was and said he was sorry I ran off. Why was he contacting me? He knew I was only 14, but I looked much younger. I was confused. My brain couldn’t work out whether it was normal for a middle-aged man to contact a young teenage girl. Shut away in my house, with none of the interactions with boys that other girls my age might get at school and parties, I was completely naïve.

It didn’t feel right, but I didn’t know what to do. I texted him back: ‘I’m fine.’

The texts kept coming. He said he liked me, that he was sorry he hadn’t been able to finish his sketch. He said he was only trying to help me. He had seen something special in me and wanted to help me understand more about what it meant.

I suppose I was flattered that this older man was paying attention to me. But it made me uncomfortable. This couldn’t be how normal people behaved, could it? What was normal anyway?

I was still in the grip of my eating disorders and depression, so to become withdrawn and quiet wasn’t new, but still my parents sensed something else was going on. They asked me repeatedly what was up, but I said nothing. I was too scared to tell them about what had happened upstairs at the spiritual fair or the texts. Maybe they would blame me. Maybe I was doing something wrong.

The texts became more frequent and the tone changed. Phil was clearly fascinated by me.

‘Can you send me some photos of you,’ he said in one text.

I didn’t want to. He started pressurising me. I sent him one photo but he came back immediately. That wasn’t what he wanted. He wanted something much more explicit – a photo of me in my underwear.

I was completely innocent. Not being at school meant I had missed out on sex education. In the books I’d read the sexual element was implied rather than explicitly detailed. I was very young in the head with regards to sexual relations, but it still felt wrong. I felt I had to do what he said, though. When I didn’t respond he called me. He spoke so confidently and smoothly, as if this was the most normal thing in the world and it was me who was being weird and difficult by not sending him what he wanted.

It felt wrong and strange to do it, but I took a photo of myself in my underwear. Why would anyone want that? I didn’t want to send it to him, but I felt like I had to because he was putting me under so much pressure. Reluctantly, I sent it. If I’d thought that was going to satisfy him, I was wrong. It only escalated further. He quickly demanded more pictures, even more explicit ones.

Next, he phoned me. ‘Guess what I’m doing right this moment,’ he said. I had no idea. I couldn’t even begin to imagine.

The idea of relationships was confusing for me. I had a skewed idea of what one should be like because my brain is wired in a very strange way. I just don’t know what is normal and what is not. I felt I had no option but to keep sending provocative photographs over text to him.

This type of correspondence went on for quite a while. I kept it secret, though. I wasn’t sure what would happen if I told anyone. Then one day he phoned me: ‘I’m coming to Brecon. I want you to meet me.’

Now I was scared. I had felt almost detached from it before, conducting things over the phone, but meeting up would suddenly make it real. Brecon was 30 miles away, so it would take some effort for me to get there.

‘Come and meet me,’ he persisted. ‘I’ll get the bed ready.’

That was it. It hit me in the face then. I can’t do that, I thought. I was scared. I still didn’t know what to do. All I knew was that I wanted it all to stop. I couldn’t think of what else to do, so I threw my phone in the bin. My parents thought it strange that I had lost my phone, but I refused to let them in on the real story. I was quite shaken by the whole experience, and it made me question his motives. Was he really a genuine psychic or was it all a sham? I suspect it was the latter.

The episode with Phil came at a terrible time, when I was full of self-loathing and wasting away physically. I was starving myself. My health really deteriorated. I had little-to-no energy, but I would still push myself to exercise for hours at a time. My hair started falling out and my nails stopped growing. My periods became very irregular and eventually stopped altogether. I started getting spots and my hair was always greasy. At my lowest points, as well as cutting myself, I’d pull out clumps of hair.

Despite my physical and mental torment, I felt like I was achieving. I felt in control, like I was doing what I was supposed to do. It might sound strange, but I felt happiness at the suffering and pain, because I thought, You can’t get what you want or be happy unless you go through pain.

For my mum and dad it was torture. They just couldn’t understand why I would do this to myself. They continued to take me to see my psychiatrist. He kept pushing me to take antidepressants. I confided in him about my need to self-harm. He took out a toy doll and said, ‘Pull the hair out of this.’

I looked at him like he was mad. How was that the same as pulling your own hair out?

‘Put tomato ketchup on your legs,’ he said, in response to the scars I was making. How could I compare the two? Self-harming was a pain I was willing to endure to take my mind off other things. The idea of putting ketchup on my leg just sounded strange. I just thought about how sticky I’d get, which repulsed me.

I was developing obsessive-compulsive disorder, and had started to value cleanliness above nearly everything else. The thought of willingly smearing ketchup on my legs was a no-no. Among my many daily rituals was obsessive hand-washing. I washed them over and over in the hottest water to kill the germs, until my hands were red. I had other rituals too, like doing specific hand movements a certain number of times. I’d turn around a certain number of times too, because I believed that if I didn’t do it something bad would happen. I lay awake half the night doing hand gestures over and over again, because if I didn’t do them 300 times I was certain something really bad was going to happen. There had been nothing to spark this. It was just something I had convinced myself of.

My OCD feels like something that has always been there. I can’t remember how or when it started. I just always had to do things. In the 1990s the condition, like Asperger’s, wasn’t that understood. In rural Wales there just wasn’t the health-care provision to advise on it.

In the grip of this mental maelstrom, my weight plummeted. I was down to six stone. My clothes hung off my skeletal shoulders. It became deadly serious then. The psychiatrist was clear about what action was needed.

‘Sophie, you have a stark choice to make,’ he told me. ‘You can either stop dancing and go on antidepressants, or go to a psychiatric hospital where they will look after you.’

The thought of going to hospital terrified me. It was no choice, really. Reluctantly, I agreed to the medication. He prescribed the antidepressant fluoxetine, known more commonly as Prozac, for my desperately low mood, and diazepam, or Valium, for the anxiety. Despite my age, they prescribed a high dosage because my situation was so serious. We were at the point where they needed to do something or there was a risk I could do something really stupid.

The medication had an immediate effect. My mood lifted and I felt less inclined to cut myself, and with the edge taken off my anxiety, everyday things seemed less stressful. For the first time I thought I could go out, and that was a big deal. I went to the pharmacy by myself and, although it sounds like such a small thing, to someone who had effectively been locked inside all her life it was massive. It was like climbing Mount Everest.

As I’d done before when I’d been feeling depressed, I tried to articulate my feelings in poetry. One from that time was called ‘My Time Is Now’.

My time for living is now.

I will no longer sleep,

As I have awakened from my long-lasting slumber.

It is too late to turn back.

The gate has closed.

My path is fixed.

Now out into the world I go!

With a smile on my face and love in my heart.

From my love I must depart.

Save your tears.

Do not cry.

Look into your memories for comfort from me.

Do not weep for you see I am already gone.

It was still a struggle, as those words demonstrate, but slowly I was engaging with the world around me. I could walk in the park near my house, go down into the town centre. By this point I was 16 and only beginning to sample things that everyone else took for granted.

The more my mood lifted, the more I wanted to meet people, so I looked to see if there were groups I could join. After years locked in my private universe, I was venturing out into the real world. What I didn’t know was that evil was waiting.