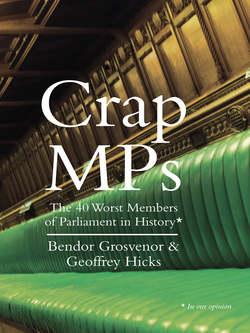

Читать книгу Crap MPs - Dr. Grosvenor Bendor - Страница 17

30. Nicholas Ridley

Оглавление(1929–93) Conservative, Cirencester & Tewkesbury 1959–92

When, in 1972, the then Prime Minister Edward Heath decided to change the direction of his government’s economic policy, he knew he would lose a number of ministers in protest. He was prepared to dismiss most of them, but seemingly calculated that the brilliant but abrasive Nicholas Ridley would be, to paraphrase Lyndon Johnson, better inside the tent pissing out, rather than the other way round. He offered Ridley the post of minister for the arts, but Ridley acidly declined the post, saying he did not believe the arts should even have a minister. Whether inside the tent or out, Ridley pissed on everyone; that was his style.

Although he was one of the most talented political thinkers of his generation, and an architect of a decade of Thatcherite economic policy, Ridley was often painfully unsuited to the demands of modern politics and the media age. This was mainly due to his unstinting inflexibility. He refused to believe in any opinion other than his own, and dismissed his critics with all the subtlety of Basil Fawlty. Once, during a BBC interview, he responded to a question by sneering, ‘That is the most stupid question I’ve ever been asked.’ When the interviewer bravely repeated the question, he replied, ‘That is the second most stupid question I’ve ever been asked.’ But the question was undoubtedly not as stupid as his answer to an interviewer on the subject of European integration in 1990; he claimed that it was ‘all a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe… I’m not against giving up sovereignty, but not to this lot. You might as well give it to Adolf Hitler, frankly.’ The Germans were not amused, and Ridley had to resign as Secretary of State for Trade and Industry.

But gaffes aside, Ridley’s intemperate nature led to serious miscalculations on matters of policy. He was right on many things, but also occasionally spectacularly wrong. For example, when at the Foreign Office during the early years of Thatcher’s government, he advocated ceding sovereignty of the Falkland Islands to Argentina, against the wishes of the local residents, a decision which in part encouraged the Argentinean junta to believe that Britain would not fight for the Islands before they launched their invasion in 1982. Arguably, Ridley’s greatest political blunder was his enthusiastic endorsement of the Poll Tax, about which he refused to tolerate objections. The tax was not his idea, but, as the Cabinet minister responsible, he wholeheartedly pushed for its immediate introduction. His phrase, ‘Every time I hear people squeal, I am more than certain that we are right’, seemed to sum up the Thatcher government’s uncaring attitude.