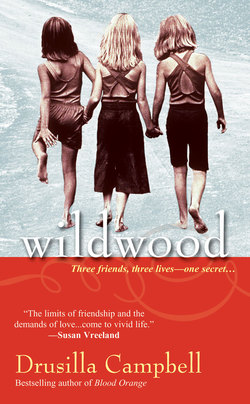

Читать книгу Wildwood - Drusilla Campbell - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFlorida

“Water walls,” Liz Shepherd said. “I’m standing on the balcony and I can’t even see the building across the street.” She held the cell phone out over the abyss. Fifteen stories down the swimming pool was a blue baguette. “Can you hear it?”

Hannah Tarwater sighed from California. “Bring it with you. Please.”

“California’s got enough natural disasters without importing hurricanes.”

“Is it windy?”

“Mostly just wet.” In the bathroom Liz had hung her drenched raincoat over the tub. Her boots were in the tub leaving muddy prints. “We’ve had more than an inch already.”

“Everything’s so dry here. I’ve practically abandoned the garden.”

They made trivial conversation; the important questions hanging in the air like wash on a line stretching coast to coast.

“I’ll pick you up,” Hannah said. “Look for the woman having a hot flash.”

“Still?”

“The doctor says a few women have it bad despite hormone replacement. I seem to be one of those.”

Liz tried to read Hannah’s voice. False cheer? Hard to tell with her, even after decades of friendship.

“The up side is I’m saving a fortune on blusher.”

They could go on like this for hours. They could pirouette around and about one hundred subjects, silly and profound, twirl through menopause, family, gardens, clothes and makeup, animals, world affairs, God, and never once come down off their toes long enough to talk about Bluegang. After so many years wasn’t there something deeply, even dangerously, strange about this determined silence? Gerard said there was.

More desultory conversation and then Hannah had to go off to a place called Resurrection House where she was a volunteer. Something about crack babies. She was always taking care of someone or something. Mother to the world, that was Hannah. Liz walked back into the hotel room, closed the sliding door, and picked up her room key and purse and went out into the hall and down to the elevator.

The hotel had more amenities than most villages in Belize where Liz and Gerard lived. On a wet and windy night she could buy a wardrobe for a family, liquor and salsa and gourmet sausage, books and souvenirs and laxatives, without ever leaving the hotel’s protection. She stepped out of the elevator and fitted her dark glasses over her ears. The fluorescent midday dimmed to a murky twilight. In the drugstore she bought a plastic spray bottle, the kind used to spritz hair or sprinkle clothes back when housewives still stood at ironing boards.

A garish sign in Spanish and English in the window of a hair salon caught her eye: NO APPOINTMENT NECESSARY. Reflected next to it she saw herself. A tallish middle-aged woman, thin and long-muscled after a tubby childhood. Her features—even her nose—seemed miniaturized in contrast to her thick dark hair like a chrysanthemum gone wild.

The salon’s Cuban manager—her elided accent was easy to identify—warned Liz the electricity might go off at any time. Did she really want to get her hair done in the middle of a hurricane?

“I’m no’ workin’ by flashligh’, ya know.”

“I’ll risk it.”

Now that she had noticed it, her hair seemed like a blind, a bosky hideout, and she couldn’t wait to escape it. She was soul-sick of hiding. Besides, a haircut always lifted her spirits, gave her confidence, which she needed for what lay ahead. But later when she stared at her image in the mirror over the bathroom sink the swingy dark hair shaped to the curve of her jaw didn’t do it. She felt no more up to what lay ahead than she had an hour earlier though certainly the cut improved her appearance. And at least she wasn’t hiding anymore.

She walked out onto the balcony, unscrewed the spritz top of the bottle she had bought and held it out beyond the balcony’s shallow overhang. The hard rain almost drove it out of her hand. For several moments she stood with her arm outstretched, getting wet to the shoulder, filling the plastic bottle with rainwater. Afterwards she screwed the top back on and put it in her purse, standing it upright so it wouldn’t leak.

She lay on the expanse of bed that faced the window, folded her hands across her stomach and thought about the week ahead.

Liz had been back to Rinconada fewer than a dozen times since college graduation almost thirty years ago. Her parents had retired from the state university system and moved to La Jolla in Southern California where Liz had visited them only twice before they died, within months of each other. But despite distance and time her friendship with Hannah and Jeanne had endured. They met two or three times a year on more neutral territory, spoke often on the phone; and now they had long, searching conversations electronically. Rinconada had become a kind of destination of last resort, a place she went to only because she knew it was expected of her occasionally. The town of her childhood was gone—the blossoming trees and one-lane roads, vacant lots alight with wild mustard—smothered in silicon, buried under new houses and chic stores up and down the main street where once she and Hannah and Jeanne had been known by every proprietor.

The Three Musketeers. Battle, Murder and Sudden Death. The Unholy Trinity.

Gone utterly yet she knew that behind and beneath the new architecture, the widened roads, she would encounter the geography of her childhood. A thousand matinees and Friday nights at the movie theater on Santa Cruz Avenue, the high school’s wide lawns, Overlook Road where they went to neck and drink beer. And Bluegang. Bluegang right in Hannah’s backyard.

Her eyelids grew heavy staring at the steel-colored wall of water, but she did not want to sleep. She sat up and turned on the bedside light. Where was her novel? Was it too early to order room service? Why did they always hide the menu?

She walked back to the window.

Somewhere, between the two buildings across the street, there was a view of the ocean; but she had only glimpsed it for an hour before the rain began. She shouldn’t have left Belize at all with a tropical storm in the forecast. This one, Claudette by name, had been promoted to a hurricane while she was at the doctor’s office that afternoon. By the time her plane took off tomorrow, the worst would be over.

She liked hurricanes in the same way she half-enjoyed earthquakes when she was a girl and the house shook and grumbled and books fell off shelves in her father’s study. There was nothing she could do about natural disasters except live through them. She wasn’t expected to take responsibility for anything so she needn’t feel like a failure for doing nothing.

If there had been a way to avoid this trip to Rinconada she would have taken almost any detour before confronting the path down the hill through the wildwood’s bay trees, gums and oaks to Bluegang. But Gerard had said, “You cannot run the rest of your life.” He knew what she was going through. Mornings when he walked into the kitchen and found her seated at the big worktable drinking her third cup of coffee, sitting where she’d planted herself in the middle of the night because dreams had awakened her as they did several times a month, staring at the whorls in the worn surface of the worktable as if by following the lines they would lead her to a place where Bluegang wasn’t, on those mornings he saw the struggle knotted in her. He would kiss the top of her head and leave her alone. He cared but what could he do? She might have endured the dreams if they were the only disturbance; but Billy Phillips, his grieving mother, and she and Hannah and Jeanne hugging at the top of the hill had become her daylight companions too. Walking down to the quay to buy fish, Bluegang was with her; browsing at the booksellers the memory came in and all at once she couldn’t read, couldn’t concentrate, couldn’t think of anything but that dead boy.

“Something’s eatin’ at you,” Divina the fortune-teller said. “Best get it out, like a worm, ’fore you waste.”

There were details she recalled clearly now, which she did not remember noticing at the time. A line of dirt around Billy Phillips’s neck. His mouth open a little, as if death had caught him in midcry. That was what she heard in her dreams. That cry. That plea for help. What she saw was a coyote.

Gerard said it was impossible that she was the only one having a reaction to the Bluegang experience. “You cannot put such things from your mind forever,” he told her, sounding very much like his psychiatrist father. Under different circumstances she would have noted this aloud and he would have sputtered defensively. But why tease when she knew he was right? He said Hannah and Jeanne would probably be grateful for the chance to talk about what happened to them. Liz didn’t think so, but she’d let him talk her into flying out to California. She had to come to the United States anyway for the other business—which she also didn’t want to think about. It was hard work, not thinking.

Had she hit on a new definition of middle age? Was it the time when the secrets of the past and the mistakes of the present came together and made life miserable and sleep impossible? Maybe this was why some people died early. Middle age took so much energy to survive they had none left for old age.