Читать книгу Blood Orange - Drusilla Campbell - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 8

Florence

In January David had received a large bonus check, the first in Cabot and Klinger’s history. He endorsed it over to Dana and told her to buy a ticket to Italy. No one got a Ph.D. in art history just thumbing through picture books, he’d said. She was both excited and fearful at the prospect of traveling alone. If she left her family for her own pleasure, fate might choose that time to punish her for being careless with what she had never deserved to have in the first place. She fretted about accidents, earthquakes, epidemics, and terrorists.

David said she was sweet and superstitious, but with the assistance of Phillips Academy and Guadalupe he would manage just fine. She had never been anywhere. Before she went to school in Ohio, she had not ventured farther from home than Los Angeles. She told Lexy she wished they’d used the bonus for a new roof.

“It’s Europe,” Lexy said. “And Italy’s practically the cradle of civilization. You’ll get there and you won’t want to come back. But you do need some backup, and I’ve got just the thing. My brother’d love to show you around. He’s been in Florence almost ten years. He’s practically a native. Plus he’s an artist. That can’t hurt.”

Dana did not want anyone to see what a klutz she was sure to be without David.

“He speaks the language—didn’t you just tell me you’re worried about not speaking Italian? He’ll love you because he loves me.”

Lexy persevered, and Dana gave in and let her call Micah.

“You have a right to have fun, Dana. Go for it.”

David said almost the same thing when he saw her off at Lindberg Field. Friends and people she barely knew told her to have fun. It offended her, the way they tossed the word out—as if fun was a universal concept everyone but she understood. She did not remember playing games with the kids she grew up with. She had never owned a doll and never wanted one. Dana had been a loner, a quiet and bookish kid who’d had part-time jobs from the time she was eleven. The first “fun” time she actually remembered having was with David at the circus in Cincinnati. Even the barista at Bella Luna, the one with five rings in her left nostril, told her to relax and have fun. As if it were that easy. Just a wish and a click of the ruby slippers and she would be able to cast off the careful habits of a lifetime. Take some risks, Lexy told her. Life isn’t about being safe all the time.

After three hours in the Atlanta airport and dinner thousands of feet over the gray Atlantic, she swallowed a sleeping pill, then until she fell asleep made lists in her head: places she wanted to visit, particular works of art she wanted to see. Before she dozed off she kissed the photo of David and Bailey she had shoved in the side pocket of her carryon. She missed them both and wished she’d stayed at home.

Micah met her at the airport brandishing his ridiculous and embarrassing sign, shocking pink, with her name in black Old English letters eighteen inches high. At the entrance to the four-star hotel where David had insisted she make reservations because it was only two blocks from the Uffizi Gallery, Micah had parked at an angle between a BMW and a Renault. He sprang from the car, grabbed her bags, and handed them to a bellman. Another uniformed person opened her door and put a gloved hand under her elbow. Her head spun and her knees almost buckled. She’d barely slept in the last thirty-six hours. And eaten virtually nothing. She leaned against the desk for support as she signed the register and gave the clerk her passport.

As she followed the bellman to the elevator, Micah said, “I’ll wait down here.”

For what?

“If you go to sleep now, you won’t wake—”

“Until I’m totally rested. That’s the whole idea.” She barely contained her annoyance. She did not want to offend Lexy’s brother, but she knew what she needed. Her body was shouting that if she did not sleep, she would die.

They stood at the elevator while the bellman held it open. Micah said something to him in Italian, the man stepped into the elevator alone, and the doors slid shut.

“What did you say to him? I need to—”

“He’s putting the stuff in your room.”

She jingled her room key in front of him. “He can’t get in.”

“He’s got a passkey.”

She slammed the heel of her hand on the up button of the elevator.

Micah said, “It’s just past five here. You need to keep moving until at least ten.”

She leaned her forehead against the wall.

“I know some people, they got here about the same time as you and went right to bed. They woke up at one-thirty in the morning. Screwed their whole day.”

The elevator appeared to have taken up residence on the third floor. She imagined the bellman going through her suitcase and finding the emergency five hundred dollars David had tucked in the pocket of her slacks.

“You can’t give in to jet lag,” Micah said, grinning. “It’s the physical equivalent of terrorism.”

She sighed. “Can I at least have a shower?”

“But don’t lie down.”

“Generally, I shower on my feet.”

“You’re done for if you lie down.”

The elevator door opened. The bellman stepped out, and she stepped in.

“If I’m not down in thirty minutes . . .”

“I’ll come get you.”

“Ring my room.”

“I’ll pound on the door.”

In the early twilight the Arno was a satiny olive-green. It lay to their right across a narrow cobbled street jammed with cars and motor scooters that filled the air with noise and stinking black exhaust. Micah told her, “If you know where the river is, you can’t get lost in Florence. Not in the Old City.” He pointed across the river to a red-tiled palazzo of pale gold stucco. “That’s where I live, the place that looks like it’s falling into the river, which it almost is. I rent the top floor from the princess who owns it.”

“A real princess?”

“Italy’s got hundreds of ’em. Mine’s eighty and poor as a peasant.”

He steered her out of the traffic onto a cobbled street wide enough for one car and stopped a block up in front of a shop selling upscale souvenirs of the city.

“That’s me,” he said, pointing to the elegantly precise pen-and-ink rendering of a Florentine skyline displayed in the window.

Dana was surprised by how good it was.

“One of these pays the rent,” he said. “I generally sell a couple a month. More during the summer.”

“I want to buy it and take it home.”

“Nah, it’s way overpriced. I’ll give you one.”

They followed the narrow street. As they stepped into the Piazza della Signoria Dana’s knees went suddenly weak. She cried out inadvertently, surprising herself. There before her were the statues she had seen in books: the immense figure of Neptune rising from the sea, and Duke Cosimo astride a beautiful figure of a horse. No matter how fine the reproduction in a book, nothing could have prepared her for the size and life that emanated from the actual statues. She forgot about having fun, about David and Bailey.

In front of the reproduction of Michelangelo’s David, Micah said, “I’ll take you to see the original in the Academia. It’s amazing, of course, practically a shrine, with camera Nazis all over the place and everyone telling you to be quiet if you raise your voice above a whisper.” He looked disgusted. “I actually like this one out here better, even if it isn’t the original. The David was meant to be public art, exposed to life. I understand all the practicalities, but I don’t like it when people treat art like it’s . . . holy. Mostly Italy doesn’t do that.”

They walked back toward the Arno through the imposing colonnade of the Uffizi Palace Gallery. “I love this city,” he said. “Everywhere I look I see something beautiful.”

His words awakened her. Until that moment she had been seeing Micah as Lexy’s eccentric and impertinent little brother, as a wild driver and a source of restless energy who would not let her sleep. But in the amber twilight of the colonnade she shed her resistance like a snake its tired skin. She saw that he was like an angel in a Renaissance painting, with his dark and curly, untidy hair, his large blue-black eyes and sensual, sulky mouth. Micah’s high energy and enthusiasm had made him seem boyish at first, but in the half shadows she could see the sadness in his face. The lines around his eyes had not come from laughing. She felt an instant empathy, and vaguely remembered Lexy saying her brother suffered from depression and had been unhappy as a boy. Happiness and grief were both written in his face along with something renegade she could not classify. As she stared at him, half mesmerized by the contrasts, she lost her footing and stumbled. He steadied her with his hand on the small of her back. His touch excited her, and she jerked away. She had not been prepared for that.

They crossed the Arno at the Ponte Vecchio, where most of the gold- and silversmiths had closed their shops for the night. It was the middle of the week and not quite tourist season. Though there was plenty of foot traffic on the ancient bridge, it did not feel crowded to Dana. They walked up the hill past the hideous facade of the Pitti Palace until they came to the little Piazza Santo Spirito and a first-floor restaurant just large enough for six tables. Micah had to duck his head as they walked in. He was perhaps six-three or four and slender; but he moved like an athlete, which surprised Dana. Jock-artist was not a common type. David was smart, but he had no interest in art.

Micah and the owner, Paolo, played together on a recreational soccer team; they greeted each other with an embrace. Their conversation was incomprehensible to Dana, but she guessed the subject was soccer because the body language of men talking sports is much the same in any country. The heads turn from side to side, the shoulders and arms pump.

At dinner Dana and Micah talked about the city and art, and she went on about her thesis topic until she felt she had to apologize for talking so much. He said he was interested and asked more questions, informed questions that started her off again. Explaining, explaining: her thesis had never seemed more real than it did that night. It was thrilling to be in Florence on her own, talking art, without Bailey tugging on her, or David looking at his watch, never telling her where to go exactly but always with his hand on her elbow steering and supporting like she might fall over if he did not hold her up. She felt guilty for her thoughts.

It was after eleven and cold when they left Paolo’s and walked toward the river through the almost empty streets.

Micah put his arm across her back. Tired and a little drunk after sharing two bottles of wine, she leaned into him and resisted his suggestion they find a taxi.

“Let’s walk,” she said.

In less than a day, this city has seduced me.

She woke up feeling headachy and slightly nauseated but ignored the symptoms, blaming jet lag and too much wine the night before. This was the day Micah was taking her to the Uffizi.

They walked past the tourists waiting in line and entered the gallery by a side door because Micah knew the right people. They made their way backward through the gift shop to the marble stairway where the guard waved them through with more jock body language. Her stomach dipped as they entered the first rooms, the walls covered with iconic art in blue and gold and umber dating back to the early centuries of the second millennium.

After the third room she went into the long passageway and sat on a bench, dropping her head between her knees.

“I’m going to be sick.” She looked around for a sign directing her to the rest rooms.

Micah blinked and pointed over her shoulder, through the window and across the colonnade where they had walked the night before and into the corner of the gallery farthest from where they were standing.

It was more than half a mile away.

When it was all over and she sat in an easy chair in Micah’s apartment wrapped in a duvet, Dana was able to laugh as Micah described in graphic detail how much worse it might have been. True, she had not made it all the way to the rest rooms, but at least she had gotten as far as the stairs leading down to them. And the line could have been worse. In the summertime there might have been fifty people staring at her while she threw up.

They talked of art and life, and Micah fed her dry crackers and soda water. As the afternoon waned, the light streaming through the tall, uncurtained windows of the palazzo changed from white to yellow to red-orange. Across the river, the bricks of Florence, absorbing the light, turned to rose gold. The room filled with long shadows and the dank smell of the river. Dana yawned and closed her eyes.

She sat up. “Do you have something I can wear back to the hotel? I need a nap.”

“Sleep here,” he said. “Later we can go out again. Nothing starts in Florence until after ten anyway. On the other side of town there’s a jazz club. You’ll like it.”

“You don’t have to babysit me, Micah. You have a life—”

“Is that how you see me? As a babysitter?”

“What about clothes?”

“Give me your key. I’ll go back to the hotel while you sleep.”

His back was to the window; the falling sun outlined him like gold encircling a medieval icon. She held her breath. He turned, and they looked into each other’s eyes. He held out his hand, then led her to his bed.

She knew exactly what she was doing. She was in a three-hundred-year-old palazzo owned by an Italian princess. She had been transported to a fairy-tale world, and she did not once think of David and Bailey or stop to ask if this was the way normal people behaved. In the Kingdom of Florence none of the old rules applied. Later, she recalled what Lexy had once said about life being full of crossroad moments, opportunities taken or lost forever.

Late that night, after jazz and slow dancing, he leaned her against a crumbling garden wall draped in wisteria, unzipped her Levi’s, and entered her with his fingers. She cried in the dark from the thrill of it. Night and the city sounds, a few feet away the voices of men and women coming out of the club where they had been moments before. And Dana impaled on her lover’s hand, crying because she had never had an orgasm like that, never knew it was possible.

She inhabited a small world that week. In the mornings Micah brought her hot chocolate and a croissant from the coffee bar at the corner. They made love amid the crumbs and might not eat again until dinner; but she felt full all the time. In mirrors and shop windows she saw the difference in herself, a look of slightly blurred and puffed fatigue, a languor in her arms and legs. Her hair was heavier, thicker, and darker than it had ever been; and she wore it loose, not tied as usual at the nape like a convent girl.

They went back to the Uffizi three times so Dana could study paintings rich in visual subtext. Da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi transfixed her. In the faces of the crowd—suspicious, venal, good-natured, Mary’s sly and gossipy attendants—she saw the emotions of living people. She walked through rooms full of two-dimensional medieval virgins holding infant saviors with the wizened features of old men, but in paintings of the Renaissance she saw faces as modern as those in the cafés and shops of Florence. This was the great breakthrough of Renaissance art. It brought mortals into art where before there had been only saints and gods.

One morning as she put her hairbrush down on the table in the bathroom she knocked a vial of pills to the floor. She picked it up and tried to read the label written in Italian, but the only word she recognized was depression. Hard to believe, easy to dismiss. During the short time she’d known him Micah had been ebullient and lighthearted. No one who was depressed could have so much energy. She thought about mentioning the pills but told herself it was none of her business. Besides, these days doctors prescribed mood-altering chemicals to almost anyone who wanted them.

In the afternoon they bicycled out of town to the Villa Reale di Castello, a sixteenth-century garden laid out with checkerboard formality. Descendants of plants gathered centuries before from countries as distant as China filled the garden with the scents and colors of spring.

They sat beside a fountain and ate a lunch of fruit and bread and cheese; and afterward they found a secluded spot and fell asleep until an ill-tempered guard rousted them and they hurried off, giggling like teenagers. Micah seemed so happy; she could not help asking him if he still got depressed.

“You know about that?”

“Lexy told me.”

“Thank you, sister dear.”

“It’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

“Did I say it was?”

“Look, it’s none of my business—”

“Hey, I’m glad you brought it up.” He did not sound glad at all. “What else do you want to know? Do I hate my mother? Am I constipated?”

She backed away from him, hands flattened in a “stop” gesture. “I asked a simple—”

“Yeah, well maybe it’s not so simple; maybe it’s so fucked up no one can figure it out anymore.”

She had no idea what he was talking about now.

“Come on, Micah, I’m getting hungry. Let’s get some of that hot chocolate at the bar. . . .” She held her hand against his cheek. “I’m sorry I pried. I never want to make you angry.”

“I’m not angry. Do I look angry?” He smiled, and she didn’t know what he was thinking. “I used to take pills for depression, but I don’t need them anymore. You make me happy, Dana. You make me happier than I’ve ever been.”

Another day they wandered through the Boboli Gardens in the rain giving names to the feral cats, getting soaked, playing chase and sliding on the wet grass. She remembered Lexy saying her brother was not a laugher. How amazing it was that now Dana knew him better than his own sister.

And every day, when they were not in galleries and churches and gardens and restaurants, they were in bed. Her vagina ached, and walking from one gilt-framed painting to another, she felt her clitoris as if it had permanently grown.

They made plans to visit Venice and Rome, Siena and Milan, where Dana had to see, must see, Bellini’s The Preaching of St. Mark in Alexandria.

“There are camels,” Micah told her, almost bouncing with delight. “And a giraffe and all these guys in fancy hats, and you hardly notice Saint Mark at all.”

With his knowledge of Italian art, and his increasing understanding of what she was looking for, he plotted a trip that would take them as far south as Palermo, where he told her about a beautiful little museum and an extraordinary painting, loaded with subtext, called The Triumph of Death. She had to see it.

“Tell him about me,” Micah said.

Not yet.

“Waiting won’t make it easier on him.”

It was Saturday. Her flight home was on Monday morning.

“It’s not one of those things I can just say.”

“What can’t you say? That you love me?” He held her face in his hands. His palms were hot and dry, and she imagined she felt his lifeline mark her cheeks, making her his forever. “You do love me. You know you do. Say, ‘I love you, Micah.’”

She whispered it.

“Tell him.”

“Let me do it my own way.”

“You want to leave me? You want to go back to that?”

That.

She would starve without Micah, dry up and blow away like sculptor’s dust.

She thought of a painting she had seen yesterday or the day before. Her days streamed together like watercolors. Or maybe it was a story she had read, or maybe she was making it up right now to explain how she felt, because only metaphor could make her emotions comprehensible. A maiden wandered into a dark and beautiful wood. She danced with a satyr and fell into a swoon. When he bent over her and asked for her will, she gave it to him.

Before they fell asleep that night Micah said, “Say it.”

“I love you.”

“Louder.”

She laughed.

“I mean it. I want to hear you yell it out.”

“I’ll wake up the princess.”

“Get up and go over to the window. Stand there and yell it across the river.”

She sat up and stared at him.

“Do it and I won’t ask you again.”

She was tired, too tired to argue. She got out of bed and fumbled for her nightgown that had fallen off the end of the bed.

“Go like you are. Don’t put anything on.” He folded his arms beneath his head. “There’s moonlight.”

“What if someone sees me?”

“You have a beautiful body. Don’t be ashamed of it.”

“Micah, I’m not ashamed. I just don’t like to make a public—”

“I’d like to put you on display in the piazza.”

The gooseflesh rose on her arms.

“The women would envy you and the men would all want to fuck you. They’d offer me money.”

She got back into bed. Pulling the blanket around her shoulders, she said, “I don’t want to do this.”

“Do what?” He bit her earlobe gently. “What don’t you want to do?”

“Stand in the window.”

He poked her gently in the ribs. “I was only kidding.”

For years Micah had sold his drawings in the Piazza del Duomo marketplace on Sundays. These drawings were much less fine than those for sale in shops around the Old City but still better than most. If the weather was good he might make several hundred Euros selling his pictures. While he was doing that Dana would have the palazzo to herself. She could not talk to David with Micah in the room listening, feeding her lines, fluttering his tongue up her inner thigh.

She thought of the house in Mission Hills, the rooms she had lovingly painted and decorated, the hardwood floors she had stripped and sanded and buffed. She allowed herself to feel a pinch of regret for what she was abandoning.

She had not used that word before.

“Mommymommymommy.”

The impulse to hang up was like a hand jerking her out the door and down the stairs.

Mommymommymommy.

She did not know what to say to Bailey. She had planned the words for David, scripted their conversation like a phone volunteer asking for campaign money. She had no spiel laid down for Bailey. “I love you” was all she could think to say that wasn’t a lie she would choke on.

“Talk, Mommy.”

She tried to swallow, but something had been added to her anatomy. At the base of her tongue there was a growth the size of a walnut.

“Dana.” David at last. “Why didn’t you call? I’ve been worried. Did you get my messages?”

“I’m fine.”

“I called the hotel, but you were never there. Even in the middle of the night.”

“I’ve been exhausted.”

“Have you been sick? What’s wrong with your voice?”

“I’m fine.”

“You don’t sound fine.”

“It’s been an incredible week.”

“You weren’t even there early in the morning.”

“Don’t be silly, of course I was there.”

She had anticipated this line of questioning.

“It’s a crazy place, David. The desk clerks are technological idiots. They probably rang an empty room.”

“I thought it was a good hotel. Didn’t you tell me it cost three-fifty a night?”

She had forgotten that digging out the truth was what David did best.

“It is a good hotel. Great breakfasts every day.” She was winging it now. “But there was a mixup with the rooms when I got there. The clerks never did get it straight in their heads.”

“I was worried.” He sounded petulant. He wanted her to tell him he had been a good husband to whom apologies were owed. He had stayed home with a difficult child while she had a good time.

Fun.

“Dana?”

“I’ve been frantic to see everything. A week isn’t long. In Florence it’s no time at all.”

“You sound like you’ve got a sore throat.”

“Yeah. A little one.”

The line buzzed in her ear.

“So,” David said, “you’ve had a good time?”

“Better than I dreamed.”

He laughed. “Gracie said I should watch out, you’d fall in love with Italy. Little old San Diego’s gonna seem pretty boring.”

“There’s so much here, David.” She wanted him to understand. “History and art. Just taking a walk, there’s so much . . . beauty. You can be in a seemingly wretched neighborhood and there’ll be an arrangement of pots or some tile or a wisteria vine . . .” Her thoughts spun forward through all she might tell him; but the effort seemed pointless. David would try to understand, but to him a picture was a picture and not much else.

She heard Bailey’s voice in the background.

“How’s she been?” She was far off her script now.

“Every day she asks me if this is the day we go to the airport to get you.”

Bailey did not understand the concept of anywhere that was too far away to drive to. David had brought home a travel video of Tuscany. “That was a mistake. She got hysterical. I guess before then she thought you were staying at the airport for some reason. I didn’t know what to do, so I called Miss Judy. She was great. The next day she taught a lesson about vacations. She’s a bloody genius, that woman, and I think Bay gets it now, that you’re not living at Lindberg Field.”

“I explained. I thought she understood.”

“The house is lonely without you. Next time you want to take a trip, I’m going too.”

She had prepared herself for guilt, but not for the sudden desire to see her husband and wrap her arms around his solid football player’s body.

She had to get back to her script.

“That’s what I wanted to talk about.” She heard the silence on the line and the sound of David’s breath. “There’s so much to see, all the little towns around have fabulous art, not to mention Venice and Rome.... It feels kind of wasteful to fly over here, spend all that money, and not see more.”

In the background, “Mommymommymommy.”

“Is there something you’re not telling me?” The lawyer was back in his voice. The trained interrogator.

She thought of the things she could say.

I love Micah Neuhaus and I’m never coming home.

Never that, never those words. They would hurt him too much; and no matter how much she loved Micah, she loved David too. And Bailey.

Dana, the smartest girl in her class, the girl who had always known where she was going and what she wanted: she knew her script and had learned her lines.

“Mommymommymommy.”

But when she tried to say something, she was interrupted by her own small voice, weeping into the musty pillow in Imogene’s spare room. For weeks she had worn shorts and a T-shirt to bed so she would be ready when her mother’s lugging Chrysler turned into the driveway.

“Are you saying you want to stay longer? How much longer? Another week?”

“No.”

“I don’t get this, Dana. What’s going on? Is there something I should be worried about?”

“I don’t want to leave, that’s all. But I’m fine, really. I just love it here, that’s all. You’re right, I fell in love. With Florence and Italy. David, I don’t ever want to leave. I belong here. It’s part of me now.”

“Dana, sweetheart, it’s a town, a city.” He laughed fondly. “There’ll be another time. One of these days I’m gonna get a big case, and when I do I’ll take you back to Florence. I promise.”

The open piazza was bright and bitter-cold and crowded with student groups. Hordes of boys and girls in signature black, mobs of young crows cawing Spanish, German, French, and guttural languages Dana could not identify, lined up to enter the Romanesque cathedral. To the right of the cathedral, Micah was one of a dozen artists who had set up tables and easels. Dana stood apart, so embarrassingly American in the yellow wool coat she would still be paying for this time next year. Bright as a target, she thought, aware that the crowds of young Europeans vaguely frightened her. Two days earlier she had ignored them and seen only the cathedral’s pink and green and white marble facade like an elaborately decorated cake.

Micah wore his struggling-artist costume on Sundays. Black turtleneck, ragged at the cuff and throat, a Greek fisherman’s cap, torn Levi’s, and sandals. He hadn’t shaved that morning and looked dissolute and pallid. As he spoke to a browser, Micah’s gold earring flashed in the sunlight and a chill ran up Dana’s legs. She wrapped her arms around herself, grateful for wool the color of midsummer lemons.

As she watched, he sold two watercolor-and-ink cityscapes to a pair of Japanese tourists. He could produce one of these in a couple of hours. He bragged that he had the Ponte Vecchio down to ninety minutes flat.

Micah looked in her direction. A wide smile opened his face, and he lifted his arm, gesturing her to him. She felt something move in her, move and stretch and snap.

She was too old, too married, too American.

And he was too young. Not in years but in the way he lived, thinking only of his pleasure, content to sell mediocre drawings in a piazza while other men erected bridges, negotiated treaties, and raised families.

Micah’s hand cupped the air more urgently. “Turn around, let me see the back.” He twirled a finger in the air. “That coat!”

Two men, passing with easels shoved under their arms, said something in rapid Italian, and Micah responded, and all three laughed.

“What?” Dana asked.

“They wanted to know if you were my American mistress. One called you Mistress Sunbeam.”

“I’m going back to the apartment,” she said. “I’m cold.”

“You can’t go. I won’t let you. You have to stay.” He motioned to a stool. “I’m sorry I teased you, honestly. It’s a beautiful coat. Here. Sit down. You watch the store and I’ll get you a coffee. Are you hungry?”

“My feet are frozen.”

“What’s the matter? What happened? Did you call him?”

Another group of Japanese tourists stopped at Micah’s table. He turned his attention to them, though occasionally, as he smiled and laughed and cajoled and took their money, he glanced sideways at Dana. When they left he showed her the pile of hundred-Euro notes.

“Not bad, huh? Give me another hour and I’ll shut down.”

She covered her face with her hands.

“What did he say?” Micah waited for her answer. When she said nothing, he pulled her hands away from her face and peered into her eyes. “Okay. Go home. I’ll close up here.”

“You don’t have to—”

“I’ll load up the car and meet you back at the flat.”

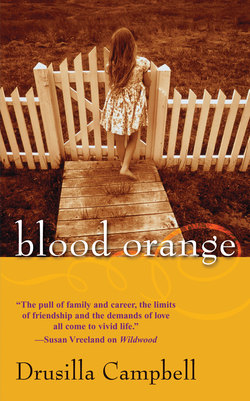

He brought fresh rolls and mozzarella, tomatoes, and blood oranges from Sicily. They ate a picnic on the bed. Dana was suddenly ravenous. Micah sliced a blood orange and nudged her onto her back, opened her mouth with his fingertips, and squeezed the fruit onto her tongue as his other hand lifted her sweater and cupped her breast. The juice was the color of raspberries and filled her mouth with sugar. Her nipples tingled as they hardened.

He shoved aside bread and mozzarella, clearing a space for them to lie. A knife clattered to the floor. He licked her sweet, sticky mouth.

I will always remember this. The smell of the fruit, the smell of him.

It was dark when she awoke, and cold. The wind was up, spitting rain against the window. In candlelight Micah sat across the room facing the bed, his sketch pad propped against his crossed knee. She pushed herself up on her elbows.

“What time is it?”

“Almost seven.”

“You shouldn’t have let me sleep. Why didn’t you wake me up?” The remains of their meal still covered the bed and floor. An orange had bled onto the duvet, staining it brown.

“I wanted to watch you. Sleeping. You’re so uninhibited,” he said. “Awake you’re always in control, or trying to be. But when you sleep your body lets go. You lie on your stomach with your legs apart. I can see all of you and you don’t care.” He held out his pad. “Here, look at yourself.”

He had drawn her thighs and buttocks and her sex with the same precise detail as he rendered the rooftops of Florence. She handed it back.

“You don’t like it?” His question sounded like a dare. “Why don’t you take it home and show it to your husband?”

She went into the bathroom and sat on the bidet. He came to the door

“Go away. I want to be alone.”

“You didn’t care how much I watched you yesterday. You let me see anything, and now all of a sudden you’re a nun. What did he say that’s turned you against me?”

She splashed warm water between her thighs, then stood and dried. She still felt sticky and ran hot water in the old-fashioned tub so hard the room quickly filled with steam. She added cold and, when the temperature was right, stepped in and sank until the water covered her to the chin.

He crouched beside the tub and watched her. She slid under, her hair floating in the water as in Ophelia’s suicide, and stayed there until her breath ran out.

His eyes shone with tears. “Tell me you’re coming back to me.”

His hand cupped the round of her shoulder. His thumb bore down into the soft tissue above her breast.

“You’re hurting me.”

“I could push you under. I could hold you under until you stopped breathing. You wouldn’t have a chance.” The steam had reddened his cheeks and brought up the wild curl in his hair. “You’re not strong enough to stop me, Dana.”

She was afraid.

“I’ve been waiting all my life for you,” he said. “You don’t know what it’s like to be me. You’re middle class to your core, Dana. You’re a taker, a user. That yellow coat says it all.”

“I’ve got to get dressed.” And get out of the palazzo and back into the hotel. She would tell the man at the desk not to let him come up. The lock on her door would keep him out.

She grabbed for the towel draped over a nearby chair and wrapped it around her. In the palazzo’s central room a triple-bar electric heater glowed near the couch. She stood in front of it and tried to dry herself without letting the towel slip. The heating element burned the back of her legs. She realized that she was barely breathing.

“Drop the towel.”

“I have to pack.”

“No. I want you to stay here, forever. I want to lock you in these rooms, feed you cheese and blood oranges and never let you out.”

“Micah, you frighten me.” His eyes drilled into her. “I can’t leave my daughter. I know what that’s like. My own mother . . .” There was no need to explain. They had talked about their lives until they knew each other’s stories as well as their own. “If I stay with you I’ll ruin her life. I can’t do that.”

Bailey needed her, and she needed Bailey. When Dana loved her, she also loved the little girl abandoned on her grandmother’s front porch. How was it possible she hadn’t understood that before?

Micah’s expression brightened. “I thought you didn’t love me.”

“I don’t know—”

“I’ve got a great idea. She can come here.”

“It wouldn’t—”

“How do you know? You haven’t even heard what I’ve got to say.” He followed her to the wardrobe where she kept her clothes. “We can make this work, Dana. I can earn plenty of money. We can move somewhere better if you want. Bailey’ll love Florence.” Dana thought of a top winding tighter and tighter. “God, wouldn’t it be great to be a kid in Florence? She’d be bilingual in no time, and we’ll send her to one of those convents—”

“David would never let it happen.” Arguing only encouraged him. She must stop talking and dress, just dress and get out.

“She can stay with us in the summer, him in the winter. Whatever.”

“You don’t know about Bailey. She has special needs.” Her voice was marbled with fear.

He stepped in close. It took all her will to keep from moving away.

“She needs you. You just said that.”

“Yes, but more. A special school . . .”

“Florence has schools,” he said angrily. “Italy isn’t Borneo.”

He had lost interest in everything but his plan. Good. He would not notice that as she dressed her hands shook. He paced around the bedroom, scheming about schools and special diets and tutors. He stopped finally and stared at her, as if surprised to see her fully dressed. She had cleared away the mess on the bed and laid out her suitcase.

“We could work this out if you wanted to. Why don’t you want to? What’s happened? You were hanging on me when I went down to the piazza this morning and now you don’t want me near you. What did he say to you? Did he threaten you?”

“He’d never do that.”

“Why not? I would.” He grabbed her wrists and drew her to him. She felt his fingers bruise her skin and heard David asking who had grabbed her and why. “I’d do whatever it took to keep you.”

“You’re hurting me.” Her pulse roared in her ears.

He looked at her and stumbled back a step, throwing off his grip. He held his hands out before him and stared at them. “I want to hurt you,” he said and began to cry. “I want to make you hurt like I do.”