Читать книгу Southern Fried Stories - Duece Dalton - Страница 2

Way Down Yonder in Dixie

ОглавлениеI grew up during the 1950's in what's called the Deep South, which is not like Virginia or those other uppity states; it comprises the lowest row of Southern states, namely, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. It is a place where only sweet tea is served and there is plenty of gravy at every meal.

Some people would say the Deep South obviously should include Florida, but the presence of so many Yankees down there automatically disqualifies it. Besides, everyone knows that nothing good comes out of Florida except I-95.

The State of Georgia was created as a buffer between the rich folks in South Carolina and the Spanish devils and pirates down in Florida. If those bad guys attacked America, they would have to fight on St. Simon's Island, Ga., instead of in South Carolina.

Sure enough, the Spanish attacked us and promptly lost the Battle of the Bloody Marsh, thereby saving South Carolina from ruin until Gen. Sherman came blazing through. The Spaniards eventually cut their losses and traded Florida to the United States, in order to get permanent ownership of Texas.

When King George let some English prisoners settle in Savannah in 1732, everything south and west of South Carolina became part of Georgia, making it the biggest state in the union, and all that land was controlled by ex-convicts.

After a misunderstanding called the Yazoo Land Fraud, the United States demanded that Georgia be split up. In 1800, Georgia sold the land comprising Alabama and Mississippi to the U.S. government for the gigantic sum of $400,000, most of which ended up the governor’s bank account. Over the course of some 200 years, the Deep South didn’t change much until the 1950's.

That decade was a great time to grow up in. It was an era of prosperity and progress for most of the United States, schools were busting at the seams with young baby boomers, and it seemed that every family owned a house, telephone, car, and a television set.

The economy was booming everywhere except in South Georgia. It lagged behind because it had stayed the same for years, mainly producing only tobacco, cotton, peanuts, and whatever else could be raised in bad soil.

I was reared in the very bottom part of the Deep South, in Waycross, Georgia. Only history buffs know it was originally Tebeauville, and no one seems to know for sure why it was renamed Waycross. Most people say it was because the railroad lines crossed there, and I've heard that the local Baptists said it was the “way of the cross.”

Regardless of the name's origin, it's appropriate for the town that's way across the swamp: Waycross adjoins the vast Okefenokee, which -- at some 400 square miles -- is larger than many states. It's so huge that no one has ever explored it all and lived to tell about it.

Waycross is the county seat of Ware County, by geographic area the largest county in Georgia, which gives the locals bragging rights to being the biggest city in the biggest county in the biggest state east of the Mississippi.

Across the country, most folks didn't hear much about Waycross until the early '60's, when the classic "Miller's Cave" became a hit song for both Hank Snow and Bobby Bare. It was about a jealous lover who caught his unfaithful girlfriend out with Big Dave, "the meanest man in Waycross, Georgia," and killed them both.

Waycross had everything that nobody likes about Florida, including swarms of mosquitoes the size of hummingbirds, but it offered none of its tropical neighbor's attractive features, such as beaches and ocean breezes. We had two seasons -- hot and hotter -- and every afternoon about 4 o'clock it rained for half an hour.

On some nights, the mosquito-killer spray truck would come down our street. Good thing our windows were open so the buzzing blood-suckers in the house got poisoned. I’m sure the chemicals that killed them couldn't harm us humans. My younger brother, Moose, liked the smell of the stuff, so he would run outside and wave at the truck, but when the driver saw a fat kid chasing him, he'd speed away.

With the railroad tracks crisscrossing Waycross, it seemed like 200 trains a day rolled through downtown. One line went right down the main street, backing up traffic and, at the end of the growing season, aggravating farmers who had truckloads of tobacco to be sold at auction.

Late one summer when Moose and I were hanging around out behind an auction shed, I encouraged him to make us a cigarette out of some stray tobacco leaves that had fallen along the way.

When he lit the rolled-up weed, a tongue of flame immediately raced all the way up to his lips. “Damn!” he said. “Next time, I’ll just swipe one of Dad’s cigarettes.” Good thing I let him smoke first so I didn’t get burnt.

When it came to taking advice, I was usually on more solid ground than Moose. My older brother, Wiz, once informed me that if I'd put a penny on a railroad track, the train wheel would squash it and make it as big as a half-dollar. I never tried it, though. I saved my coins for the Coke machine, which demanded a penny and a nickel for a 6 ½- ounce bottle. For a dime more, we could buy salted peanuts, which we'd pour into our drinks and munch on as we sipped. We would check the bottoms of the bottles to see where they were filled. Some of our Cokes came all the way from Rock City, Tennessee.

There are no rocks in Waycross, and the soil is not the red Georgia clay of song and story. It's white sand that once was ocean bed, and because it's below sea level, water flows north after a hard rain. In our front yard, we could dig a hole about six inches deep, it would fill with water almost immediately, and before long a frog would jump in it. Moose would then skillfully gig the croaker with a knife stolen from the kitchen. Early on summer evenings, we'd sit on a blanket in the yard and watch the cloud-to-cloud lightning. But only if nothing good was on TV.

In our little town, we could go wherever we wanted, usually on our bicycles. I had a nice red one that I learned how to ride after just one lesson. Dad put me on it, gave me a big push, and yelled, “Start pedaling, damn it!” So I did, pedaling until I was out of sight so I could avoid any more lessons.

Most of the men in Waycross worked for the Southern Railroad, whose local operation included a huge repair shop and a switching yard. It employed only white men, most of them for such complicated jobs as cleaning and painting boxcars.

Like all the Deep South towns, Waycross was strictly segregated in the '50's. Black people lived in older houses across the main railroad tracks from white folks, and we were told not to talk to them.

They attended their own schools, shopped at their own supermarket, bought used cars from their own dealership, and got their haircuts at their own barbershop. The black undertaker and the black preacher drove Cadillacs, but none of their neighbors had much money. They were hired as cooks or maids but couldn't get professional jobs, such as smoothing out wet cement.

Black folks had their own taxi service, too. Our part-time nanny, Viola, would arrive at our house in a Walker cab to care of my little sister, Tootle, so that Mom could work as a bookkeeper at the local Ford dealer.

Viola was a great cook who dipped snuff and spit in a soup can while she watched soap operas, and she didn’t put up with any backtalk from little white kids. After a spanking she gave Moose, he shaped up. Sometimes he and Tootle would sit in her lap while she would hum them a melody.

I've always wondered why so many black people stayed in Waycross instead of moving to Atlanta, where they could get better jobs.

Waycross is 240 miles south of Atlanta, and 60 miles west of the coastline, with US 1 running right through it, only to jig 60 miles off to the east, through the swamp and on into Jacksonville.

Interstate highways might have been running through Eisenhower's mind, but only two-lane winding roads ran through South Georgia, and God help you if you got stuck on one behind a lumbering, overloaded pulpwood truck. Following them were long lines of cars with fins the size of surfboards, big battleships that got about five miles to the gallon.

We had gas stations on every corner, and one time they had an all-out price war. I don’t know who started it, but for a while there you could fill up for 10 cents a gallon, unless you had New York license plates, in which case you were charged the customary 25 cents per gallon.

Back in the '50's, it seemed that every resident of New York City thought it was mandatory that they drive down US 1 to Florida once each summer.

Noting that Waycross was the last Georgia town on their way south, carloads of Yankees would barrel on through it. What they didn't take into account was that a long stretch of the Okefenokee lay between there and Jacksonville.

Just out of town on US 1 stood a big sign saying, "JACKSONVILLE IS 93 MILES – NO GAS, NO MOTELS, NO KIDDING – TURN AROUND HERE TO RETURN TO WAYCROSS." For whatever reason, some Yankees went past it, and past a special turnaround lane, and drove on into the dark swamp. Maybe some of them made it all the way to Florida.

But even for those New Yorkers smart enough to stop and pay a quarter for a dime's worth of gasoline, the trip sometimes went south in more ways than one.

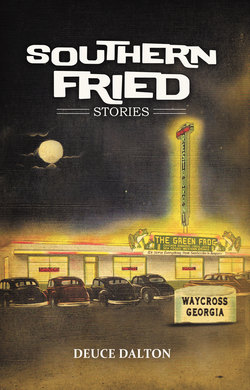

To fill their bellies as well as their tanks, they had to go to the Green Frog, the only restaurant in town. Bemused by the regional fare on the menu, the unsuspecting Yankees would order fried frog legs and, of course, fried peach pies.

The joke was on them the next day, though, when they would take off without knowing the next restroom was more than 90 miles away. After a while, with desperation setting in, some would have their pit stop delayed another 20 minutes or so while they hastily signed a speeding ticket and promised the trooper that they'd slow down.

Back then, cars lacked air-conditioning, and the Yankees found out that they couldn’t even lower their windows to make the ride more bearable. The odor of the surrounding swamp was worse than the smell inside.

I didn’t feel any pity for those Damn Yankees until, at age 7, I was informed that I was born on Long Island, New York. I was mortified! What if people that I knew found out I was really a Yankee? I knew that Wiz was born in Chicago, and that he got beat up all the time because he talked funny.

At least I didn’t talk like a Yankee, and both my parents were from the South, so no one ever suspected. But whenever the subject came up later on in life, I would point out that I was born on the southern part of Long Island.

Back in the sunny South, we'd spend winter days outside, playing baseball, war, or -- my favorite -- football. Like most Southern towns, Waycross was crazy about football.

Just like the University of Georgia, our high school had a bulldog mascot and wore red and black uniforms. One year, the Waycross Bulldogs won the state championship, defeating the Red Elephants of Gainesville, way up in North Georgia. We listened to the game on a transistor radio.

On my last visit to Waycross, I found it full of memories but much smaller than it used to be. The Green Frog was gone, the tallest building in town was boarded up, and the movie theater was closed. Since the interstate highway bypassed the town, no more Yankees were invading from up north.

After so many people had moved away, probably to Atlanta, Waycross had to consolidate the city and county high schools. Since they couldn’t keep the same mascot, some Yankee renamed them the Ware County Gators. How could it be? They'd copied the Florida Gators! And everybody in South Georgia knows that nothing good comes out of Florida except I-95, whether it's a Spaniard or a mascot.