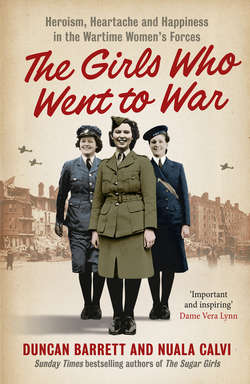

Читать книгу The Girls Who Went to War: Heroism, heartache and happiness in the wartime women’s forces - Duncan Barrett - Страница 9

1 Jessie

ОглавлениеThe morning of Sunday 3 September 1939 was a sunny one, and Jessie Ward was out digging potatoes in the garden of her family’s house in the little village of Holbeach Bank, Lincolnshire. A petite girl with big blue eyes and dark hair, she looked far younger than her 17 years, but despite her slight build her mother always made sure to keep her busy with chores. That particular day Mrs Ward was looking after a sick friend’s little girl, so Jessie had even more to do than usual.

Just after 11 o’clock that morning, Mr Ward called his wife and daughter into the living-room, where they found him listening intently to the bulky wooden wireless set. There was a crackle, and then the clipped tones of Neville Chamberlain rang out of the machine. ‘This morning,’ he announced, ‘the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note, stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us.’

Jessie saw her mother and father exchange an anxious glance.

‘I have to tell you now,’ the Prime Minister continued, ‘that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.’

Mr Ward leaned forward, holding his head in his hands. ‘It can’t happen again,’ he muttered. ‘It just can’t.’ Jessie knew that her father had spent much of the last war watching his fellow soldiers in the Royal Warwicks being gassed and slaughtered in front of him, and had witnessed his best friend being shot in the head.

‘Well, we’ll probably be invaded, being so close to the coast,’ said his tiny wife, matter-of-factly. ‘I’d better take Tina back to her mother. Jessie, you’ll have to do the Sunday dinner.’

‘Yes, Mum,’ Jessie replied, as the little girl began to howl. Whether it was because of the imminent invasion, or because she was missing dinner, Jessie wasn’t sure, but she was surprised to find that she herself felt nothing at all. Unlike her father, she had little idea of what war might bring, since the last one had ended four years before she was born.

Jessie went back out into the garden, and nodded over the fence at Mr Crawford, the elderly man who lived next door. ‘Do you think we’ll be invaded?’ she asked him.

‘Oh, don’t worry,’ he told her. ‘Even if we are, the Germans aren’t going to hurt the likes of us.’

Jessie’s father came marching out into the garden just in time to catch Mr Crawford’s remark. ‘You silly bugger!’ he shouted. ‘You’re the first ones the Nazis’ll get rid of. Your wife is blind and you’re an old man!’

‘They wouldn’t do that,’ Mr Crawford protested weakly.

‘They would,’ retorted Mr Ward. ‘I know the Germans. They wouldn’t waste food on people like you!’

Jessie was shocked – not so much by her father’s anger, or by the grim prophecy in his words, but at the fact that he had said ‘bugger’. She realised she had never heard him swear before.

In fact, it was rare to hear Mr Ward raise his voice at all, other than where Germans were concerned. He was a kindly man, whose health had never been the same since he had returned from the trenches 20 years earlier. It didn’t help that he had to work six days a week, hammering away in his little cobbler’s shop – and keeping it open until 9 p.m. most nights for the sake of the local farm labourers. Most of his customers only had one pair of dilapidated old boots to their name, but Mr Ward would work miracles on them, knowing that their owners couldn’t afford to buy new ones.

While Jessie’s father was out working all hours, his wife had free rein to boss their only daughter around. Fanny Ward was small, pretty woman, but her demure exterior belied a sharp temper, and Jessie had learned from a young age never to displease her. Every time she dropped a ball of wool she was winding or accidentally broke a cup in the kitchen, she was bound to get a clout round the ear.

Whenever she could, Jessie escaped to her grandmother’s house to play on their beaten-up old piano. She had inherited a talent for music from her father’s side of the family, and when she sat and played her cares seemed to melt away, the music transporting her to a realm of pure joy. Mr Ward was proud of his daughter’s musical talent, and put aside a shilling a week to pay for her to have lessons.

The only thing that came close to playing, as far as Jessie was concerned, was dancing. As she grew older, she and her best friend Joan started attending the dances that were held every week at the little church hall in Holbeach Bank. She knew she was a good dancer, and she enjoyed showing off her skills, but her mother made sure that her confidence never went to her head. ‘Do I look all right, Mum?’ Jessie asked her one night, as she was about to head out. ‘You’ll do,’ Mrs Ward replied. ‘But who’s going to be looking at you, anyway?’

When Jessie left school her piano playing proved a useful source of income, as she began giving lessons to the village children. But most of her time was still dictated by her mother, who kept her busy helping with knitting for the local wool shop, doing the gardening, cleaning the house, cooking and running errands.

There wasn’t much to look forward to in Holbeach Bank, beyond one day marrying a boy from the village and moving out – and to begin with, the advent of war didn’t make much difference to the sleepy community. Most of the local lads were farm labourers, so they were exempt from conscription, and the village was so tiny that no one thought it worth installing air-raid shelters.

But for Jessie’s father, the new war brought with it a new sense of purpose. He was thrilled when he heard on the wireless that men up to 65 were needed to help defend their country, as part of the Local Defence Volunteers or ‘Home Guard’. Now Mr Ward spent his spare time back in uniform, practising his marching and going out on night patrols, armed with an old First World War rifle. Wherever he went, he walked about with his chin up and his back straight as a rod. The neighbours joked that if you cut him, his blood would be khaki.

But Jessie’s father’s new pastime meant that she was left alone in the house with her mother more than ever, and she began to grow desperate for something that would take her away. One day, she spotted an advert for a waitress at a little truckers’ cafe on the road to Holbeach proper. It was hardly glamorous, more of a ‘greasy spoon’, but Jessie jumped at the chance to get out of the house, hurrying to the cafe and offering her services.

‘Are you sure you want the job?’ asked the woman who ran it, looking at the slip of a girl in front of her. ‘We get some pretty tough types in here, you know.’

‘Oh, that doesn’t bother me,’ Jessie replied. If she could put up with her mother, she was sure she could handle a few truckers. The other woman didn’t look quite convinced, so Jessie suggested helpfully, ‘If you like, you can serve the posh customers, and I’ll look after the tough guys.’

‘You’re on,’ said the woman, hastily handing Jessie an apron as a group of burly-looking men came in through the door.

On the evenings when Mr Ward was at home, the family always gathered to listen to the BBC’s 9 p.m. bulletin and hear the latest news of the war. In May 1940 they all sat in shock as they heard that the British Expeditionary Force was being evacuated from Dunkirk. An armada of fishing boats, crabbers, trawlers, shrimpers and yachts had answered the call for assistance, bringing back hundreds of thousands of exhausted soldiers while the Luftwaffe pounded them from overhead.

The new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, told the country that the evacuation was a ‘miracle of deliverance’, but Mr Ward wasn’t so easily convinced. ‘We ran away from those Jerrys with our tails between our legs,’ he said, shaking his head sadly.

Back on home soil, the effects of the evacuation were soon felt around Holbeach, as the battered British Army regrouped and replenished itself. Soon soldiers started to be seen around the village, and a nearby stately home called Bleak House was requisitioned by a Royal Artillery regiment.

Jessie knew the house well, since her friend Joan was the niece of the caretakers there, Mr and Mrs Hedqvist, who encouraged Jessie to come and play the grand piano in the drawing room whenever she liked. ‘We don’t see much of the soldiers really,’ Mrs Hedqvist told her when she turned up to practise one day. ‘They’re mainly just using the kitchens and the dining room for their officers’ mess.’

As Jessie approached the magnificent piano, Mrs Hedqvist sat down on a chair and took some knitting out of a little bag. She often liked to knit while Jessie played, and the regular klick-klacking was almost as good as a metronome.

Jessie began to run through a few scales. Then, when she felt she was properly warmed up, she moved on to a piece she had recently learned, a nocturne by Chopin in G minor. She was pleased to find that she could get through the whole thing without the sheet music – and even more pleased, when she reached the final notes, to hear applause echoing around the drawing room.

Jessie looked over to Mrs Hedqvist, but the caretaker was still busy with her knitting. Then she turned and looked behind her, where she discovered the source of the clapping. A young soldier was standing by the doorway, clearly enraptured by the music. ‘That was wonderful,’ he exclaimed, beaming at Jessie enthusiastically.

‘Oh – hello!’ Jessie replied, her cheeks flushing red. ‘I’m glad you liked it.’ The soldier was a couple of years older than her, with dark hair and a beautiful smile, and Jessie found him very attractive.

The young man approached the piano. ‘I don’t suppose you take requests?’ he asked her.

‘Well, what do you like?’ Jessie said. ‘If I don’t know it, you can always hum the tune and I’ll try to pick it out.’

‘How about “There’ll Always Be an England”?’

‘Oh, that’s easy,’ Jessie told him, launching into the popular tune. But what seemed easy to Jessie obviously impressed the young soldier. As she played, she looked up now and then, and every time she saw him grinning from ear to ear, clearly enchanted by her performance.

Jessie had come to Bleak House intending to practise her classical pieces, but that afternoon she found herself playing a host of popular tunes instead as the young man requested one song after another. Soon they were both so lost in the music that they had completely lost track of time, and it was only when a grandfather clock in the corner of the room began to chime that the young man suddenly came to his senses. ‘Oh my goodness,’ he said. ‘I’m supposed to be on duty!’

He dashed for the door, shooting Jessie another quick smile as he went.

Jessie remained seated at the piano for a moment. ‘That was charming, my dear,’ Mrs Hedqvist commented, giving her an encouraging smile.

Jessie had almost forgotten that the older woman was still in the room. ‘Oh, thank you,’ she replied, as she stood up and brought the lid down over the keys. But somehow she wasn’t quite sure that it was the music which Mrs Hedqvist had been charmed by.

The following day, Jessie was on her bike, riding home from her job at the greasy spoon, when she saw the young soldier cycling towards her on the other side of the road. ‘Oh, there you are,’ he called as he spotted her, wheeling around until they were side by side.

‘Hello again!’ Jessie said. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘Looking for you, of course,’ the soldier replied cheekily. ‘I’ve just been round to your house and your mum said you’d be coming along this way.’

He must have got my address off Mrs Hedqvist, Jessie thought. She couldn’t help smiling.

‘Would you mind if I cycle with you?’ the young man asked politely. ‘I thought you might like some music on your way home.’ As they pedalled away, he began singing ‘Wish Me Luck As You Wave Me Goodbye’, one of the songs Jessie had played for him the day before. She noticed that he remained perfectly in tune throughout, and his delight in the music shone through just as it had in the drawing room at Bleak House.

‘That was lovely,’ Jessie told him when he came to the end of the song.

‘I’m glad you liked it,’ he replied. ‘I take requests too, you know.’

Jessie laughed. ‘All right, how about “Run Rabbit Run”?’ she suggested.

The man launched into a spirited rendition of the song, and for the rest of the two-and-a-half-mile journey, he kept her entertained with one tune after another.

In between songs, Jessie learned that the young man’s name was Jim Winkworth, and that he had worked in the kitchen of a top London restaurant before joining the Army Catering Corps. ‘I’m in charge of the food for all the bigwigs,’ he explained.

‘Well, I suppose you could say I work in catering too,’ Jessie replied, ‘but we mostly serve truckers, not Army top brass!’

‘Oh, I’d swap with you any day,’ Jim told her. ‘You’d be surprised at the table manners of some of the majors and colonels.’ But it was clear when he talked about the fancy dinners they laid on for the officers at Bleak House – with the finest crystal and silverware the grand stately home had to offer – that he loved his job very much, and took great pride in getting every detail just right. ‘When I was out in France, we’d have killed for a pantry stocked as well as the one they have here,’ he told her wistfully.

‘You were in France?’ Jessie asked, surprised.

‘Oh, yes,’ Jim replied. ‘I was sunk twice on the way back from Dunkirk, but both times I got pulled out of the water. In the end I came back on a little fishing boat.’ He grinned at her. ‘I guess I must have just been born lucky.’

‘Most people would call being sunk twice pretty bad luck!’ Jessie pointed out.

‘Well,’ Jim shrugged, ‘there’s plenty of men who didn’t make it back at all.’ After a moment’s silence, he began to sing again. Clearly whatever horrors he had seen had only made him more determined to embrace the joy of life.

When they got to Holbeach Bank, Jessie invited Jim in for a cup of tea, and soon he was entering her parents’ little house for the second time that afternoon.

‘Oh, he found you then?’ Mrs Ward commented dryly as Jessie ushered the young man into the kitchen.

‘Yes, Mum,’ Jessie replied, hoping her mother wasn’t going to be rude to him.

‘So, Jim, where do your family come from?’ Mrs Ward asked, as she plonked the teapot down on the table, gesturing for Jessie to pour the tea.

‘To be honest, I have no idea,’ he told her. He explained that he had spent his childhood in a Dr Barnardo’s orphanage in Hastings and had never found out who his parents were.

As she listened to the sad story, Jessie’s heart went out to Jim, but his words had a different effect on her mother. ‘I’m not keen on that one,’ she told Jessie, after the young man had set off back to Bleak House. ‘He’s got no family, no background. You don’t know who he is.’

‘Neither does he, Mum,’ Jessie reasoned. ‘You can’t hold that against him.’

But Mrs Ward shook her head firmly. ‘You don’t want to get involved with him,’ she said.

Jessie took little notice of her mother’s advice, however, and soon Jim was stopping by at the greasy spoon several times a week to see her. They spent hours at a time cycling around the countryside together, pausing every now and then for a kiss and a cuddle, until it was time for him to accompany her back home.

Jim hadn’t failed to notice Mrs Ward’s coolness towards him. ‘I don’t think your mother likes me,’ he told Jessie one day, as they were cycling back to Holbeach Bank.

‘Oh, don’t worry. She doesn’t like anyone!’ Jessie replied, trying to make light of the situation.

But Jim was uncharacteristically serious. ‘You know, it’s hard for me to meet new people,’ he told her. ‘They always want to know about my family.’

‘Well, I don’t care who your parents are,’ Jessie declared. ‘And anyway, the way some families are, you’re probably well off without one!’

But despite Jessie’s words, Jim was determined to win her mother over. One evening, he turned up at the little house in Holbeach Bank bearing an enormous fillet of smoked salmon. ‘Don’t worry, I haven’t stolen it,’ he told Mrs Ward when he saw the suspicious look in her eye. ‘We over-ordered at the officers’ mess and it was going to be thrown in the bin.’

‘Well, in that case, I suppose we’d better eat it,’ Jessie’s mother replied, taking the fillet off to the kitchen.

When the food was served, even Mrs Ward had to admit that the salmon was delicious, and fresher than anything the family had eaten since the start of the war. But her frostiness towards Jim didn’t thaw one bit.

Mr Ward, on the other hand, clearly enjoyed having a soldier in the house. ‘You know, the cooks are the most important people in the Army,’ he declared over dinner, looking over approvingly at Jessie’s guest. ‘When I was in the trenches, they were the ones who kept our peckers up. As Napoleon said, an army always marches on its stomach!’

After Jim had left at the end of the evening, Jessie’s father turned to her. ‘I like that young man,’ he said. ‘And I’m glad that he’s an Army lad, not one of those stuck-up Navy or Air Force types.’

But despite the wonderful salmon, the expression on Mrs Ward’s face made it clear that her opinion of Jim hadn’t altered one bit.

Jessie soon discovered that Jim was forming his own views about her mother as well. ‘You know, you take too much notice of her,’ he announced one day while they were out cycling. ‘You shouldn’t let her boss you about so much.’

‘Well, there’s no point arguing with her,’ Jessie told him. ‘It only makes things worse.’

‘Maybe,’ Jim replied. ‘But don’t let her keep you under her thumb.’

The more time Jessie spent with Jim, the more she felt herself falling in love with him – but her feelings were of no concern to the Army. One day, out of the blue, orders went up at Bleak House announcing he was being transferred to Sleaford, 25 miles away. There were no more romantic bike rides after work, and Jessie found she missed Jim terribly.

Fortunately, he was billeted with a kind local vicar who allowed him to use the phone once a week. He would write to Jessie and let her know what time he would be calling, so that she could queue up at the phone box in the village for a quick snatched conversation. It was wonderful to hear his voice, even only briefly, but afterwards she always returned home glumly, knowing it would be another seven days before they could speak again.

Before long, Jim was sent even further away, to Woodhall Spa, where they could no longer even talk on the phone. Now Jessie lived for his letters, which arrived faithfully every other day. He was a natural writer, and the two of them filled pages and pages with heartfelt reminders of their love.

When Jim wrote one day and asked Jessie if she would marry him, she knew instantly that her answer was yes. But she also knew that her mother would do her best to talk her out of it.

Jim’s words echoed in Jessie’s mind: ‘Don’t let her keep you under her thumb.’ She picked up a pen and quickly wrote back accepting Jim’s proposal, making sure the letter was signed, sealed and posted before she went in to tell her parents the news.

‘Jim’s asked me to marry him – and I’ve said yes,’ she announced excitedly, when she found them together in the living room.

Mrs Ward shot an annoyed look at her daughter, but she could see it was too late to change her mind. Instead she said coldly, ‘Well, you’ll have to wait until the war’s over. It would be very unwise to marry before then.’

Jessie was determined not to give too much ground. ‘We’ll have to wait and see,’ she said boldly.

Her father grinned at her. ‘I don’t mind what you do love, as long as you’re happy,’ he said.

A few weeks later, when Jim was granted a day’s leave, he and Jessie met up in King’s Lynn. There he presented her with the most beautiful ring she had ever seen – it was made of platinum and encrusted with tiny diamonds.

As much as Jessie was thrilled about her engagement, it made life at home even more difficult. Her relationship with her mother was frostier than ever, and she realised that, even if she did defy her and marry Jim while the war was still raging, with the Army moving him around constantly, she would still be stuck at home until he was finally demobbed.

It didn’t look like the war would be over any time soon, either. When they gathered around the wireless in the evenings, Jessie and her family heard reports of aerial bombings in London, Birmingham, Liverpool and other big cities, including nearby Peterborough. A few bombs had even landed near Spalding. ‘Those blooming Germans are walking all over us,’ Mr Ward fumed.

Jessie was beginning to wonder what she was doing to help with the war effort. All she did was spend her days serving beans on toast. Surely there was something more she could do – perhaps even something that would have the added bonus of getting her out of Holbeach Bank.

Ever since Dunkirk, stories had been circulating about the brave ATS girls who had travelled to France with the British Expeditionary Force. Some had heroically escaped after having been captured by the Germans, while others had endured terrifying dive-bombing by the Luftwaffe. Their efforts had proved that the women’s forces deserved to be taken seriously, and now a massive recruitment drive was underway.

Jessie had seen the posters and advertisements up around the village, calling for girls to join the ATS – ‘YOU ARE WANTED TOO!’ they proclaimed in large, bold letters, alongside an image of a young woman marching in uniform. Jessie liked the idea of joining the Army, like her father, and when she wrote to tell Jim about her idea he was supportive. But she had a feeling that if she spoke to her mother, she would try to put a dampener on her plans.

When a friend who lived ten miles away in Boston invited Jessie to come and visit her for the weekend, she realised it was the perfect opportunity for her to join up without any interference. She took the bus into Grantham, where she knew there was an ATS recruiting office, and was ushered into a hall where a male Army sergeant was seated behind a desk. He took down her name, address and date of birth, and told her she would be hearing from them shortly.

‘I’ve signed up for the ATS,’ Jessie told her parents, as soon as she got back home after her holiday.

Mrs Ward didn’t even look up from her knitting. ‘Well, the Army ought to teach you what hard work is,’ she muttered.

‘I don’t mind working hard,’ replied Jessie. After all, her mother had been treating her as a domestic drudge for years.

Mr Ward, of course, was over the moon at the thought that he was going to have a daughter in khaki. ‘My Jessie’s going to win us the war, you know,’ he began telling anyone in the village who would listen.

Now that she had made the decision to join up, Jessie’s excitement was growing, but it soon began to be mingled with impatience. She had volunteered in December of 1941, and had been rated ‘A1’ at a medical exam in Grantham just before Christmas, but she was told that it wouldn’t be until the new year that the Army would get around to calling her up.

At long last, one crisp January morning, an official-looking envelope arrived on Jessie’s doormat. She tore it open to find a railway warrant and instructions for getting to an ATS training camp at Leicester the next day. She was to bring just one small suitcase, containing two pairs of pyjamas.

Jessie didn’t own any pyjamas, so she rushed into Holbeach to buy some, stopping off along the way to let her boss at the greasy spoon know that she was leaving to join the Army. ‘Well, I can’t argue with that!’ the woman said, wishing her luck.

The next morning, Jessie was up bright and early, ready to begin the journey to Leicester. To Mr Ward, it was a red-letter day, although his wife treated it just like any other. As far as she was concerned, Jessie might have been setting off for her usual shift at the cafe, not leaving home for the duration of the war.

Right now, though, nothing could dampen Jessie’s spirits, and she walked the two and a half miles to Holbeach Station fizzing with excitement. At the station, she presented her railway warrant and boarded a train to Spalding, where she had been instructed to make a connection that would take her to Leicester.

As she got on the second train, Jessie spotted a couple of girls she recognised from her medical in Grantham, and soon they had introduced themselves and were chatting away. One of them, Mary, was tall and slim, and carried herself with an air of quiet confidence. The other, Olive, was more cuddly-looking, with glasses and an infectious laugh.

As they got to know each other, the girls talked about their reasons for joining the ATS. Olive, it turned out, had signed up after a love affair turned sour. ‘I just got so fed up that I had to leave!’ she told Jessie and Mary with a giggle.

When they arrived at Leicester station, the girls were met by a railway transport officer, who pointed them in the direction of a fleet of ATS lorries. They clambered up over the tailgate of one of the vehicles, along with a group of other young women. They were all anxiously clutching little suitcases, with the same expression of bewilderment on their faces. They didn’t exactly look like an Army in waiting.

When the girls finally arrived at the barracks it was well into the afternoon, and they were led into the canteen for a late lunch. Jessie went up to the counter to get her food, and was surprised to find a familiar face serving her. It was Peggy Hogg, a girl she remembered from school, who was now on permanent staff at the camp as an ATS orderly.

‘Fancy seeing you here, Peggy!’ Jessie exclaimed, as the girl slopped a portion of mashed potato onto her plate. ‘I didn’t know you were in the Army.’

‘Oh yeah, I’ve been here a year now,’ Peggy replied with a sigh.

As Jessie returned to her seat, she couldn’t help feeling a little sorry for her old schoolmate. Wasn’t joining the ATS supposed to be about doing something important and exciting? Yet here was Peggy still at a training camp a year after she had signed up, with nothing more thrilling to do than doling out slop.

When they had eaten, the new recruits were led to the stores to be issued with their kit. A woman took one look at Jessie’s diminutive form and declared, ‘Size one in everything, and if it’s still too big you can take it in yourself with your hussif.’

The ‘hussif’ – or ‘housewife’ – was a sewing kit issued to every member of the services, and was just one of a bewildering array of items that Jessie soon found herself piling into a large Army kitbag. First there was the basic ATS uniform: shirt, skirt, tunic, tie and cap, along with stockings, suspender belt and bra – plus three pairs of voluminous khaki bloomers, which were known throughout the ATS as ‘passion killers’. Jessie found that two of hers were broadly speaking wearable, but the third for some reason stretched from above her bosom to below her knees.

Next came two pairs of heavy lace-up shoes, plimsolls, a top and shorts for physical training, a field dressing, knife, fork, mug and spoon (collectively known as ‘irons’), towels, hairbrush, comb and toothbrush, plus special brushes and implements for polishing shoes and buttons.

On top of all this, every girl was handed a gas mask, complete with a haversack to carry it in, and – last but by no means least – a supply of sanitary towels. The cost of providing these had been met by the generous Lord Nuffield, the founder of Morris Motors – and as a result they were known unofficially as ‘Nuffies’. Little did he know that in addition to their intended purpose, they were used by resourceful girls in uniform for everything from cleaning buttons to straining coffee grounds. Those with loops were even fashioned into makeshift eye-masks, popular with night-shift girls trying to catch 40 winks in the daytime.

By the time they were all kitted out, the new recruits were ready to retire for the evening, but first they had to face the dreaded Free from Infection parade, or FFI. Lining up one by one, the girls were asked to pull their knickers down as the doctor inspected them for parasites and venereal disease, before their armpits were checked for lice, their hair gone through with a nit comb and their chests and backs examined for rashes. For the sorry few who failed the nit-comb test, the treatment offered a further humiliation: their hair was cut short and covered in a thick black paste made from coal tar, paraffin and cottonseed oil, before being wrapped up in a turban.

Finally, once the FFI was over, Jessie and the other girls were issued with a pair of sheets each and led to the large wooden dormitory huts, each containing 30 hard iron beds, which were to be their home for the coming weeks. Each bed had a mattress made up of three separate square parts or ‘biscuits’, as well as an uncomfortable-looking straw bolster for a pillow, and three grey blankets for warmth.

Jessie was disappointed to find that she wasn’t sharing a dorm with Olive or Mary, who were both in the next hut along. Instead, she was bunking with a group of strangers, who, judging by their accents, hailed from every inch of the country, from Lands End to John o’ Groats. The cacophony of different voices was quite something, but it was the Londoners who really stood out to Jessie. Whether cut-glass or Cockney, they all sounded so confident and loud, and beside them she felt like a bit of a country bumpkin.

The next morning, Jessie packed up her civilian clothes in her suitcase so that the Army could post them home to her parents, and dressed in her new ATS uniform for the first time. Then she and the other girls in her hut grabbed a quick breakfast in the canteen before they were introduced to one of the staples of basic training: drill practice.

The girls lined up on the parade ground as a red-faced male sergeant strode up and down in front of them. From the sour expression on his face, he obviously wasn’t too impressed with what he saw. ‘When I call “Attention!” I want you to bring your left foot in to your right,’ he announced. ‘Ready? Atten-shun!’

Jessie instantly snapped to attention, her back as straight as a pole. Thanks to her father’s example, she had a pretty good idea of what military posture looked like.

‘As you were,’ the sergeant shouted. ‘Now, ri-i-ght turn!’

Jessie pivoted 90 degrees to her right and sharply brought her feet back together. But, looking ahead of her, she could see some girls were facing the wrong way.

‘Don’t you know your right from your left?’ the sergeant shouted at them, exasperated. The confused girls giggled, and awkwardly shuffled round to face the front.

‘Now, when I say, “By the left, quick march,” you’re going to leave on the left foot with the right arm up,’ the man told them. ‘Forget what your mothers told you and make sure you open your legs.’

There was barely time to take the information in before he bellowed, ‘By the le-e-ft, qui-i-ck MARCH!’

The girls began moving forward as the sergeant bellowed, ‘Left! Right! Left! Right! Left! Right!’ Thanks to her dancing experience, Jessie found it easy to keep in time, and to make sure her arms were swinging alternately with her feet. But not all her colleagues were finding the training so straightforward. The basic marching movement was too much for some of them to grasp, and they were waddling forward with arms flailing out randomly.

Their posture didn’t exactly match Jessie’s straight-backed bearing either. ‘Stop slouching, and keep your legs open,’ the sergeant bellowed at the group. ‘What are you, a bunch of pregnant virgins?’

In the face of such a nonsensical insult, the new recruits struggled not to laugh.

When they weren’t drilling, the girls spent much of their time at the training camp in lectures, scribbling down notes in little exercise books. There were talks on the history of the local regiment in Leicester, and on the basics of Army discipline. ‘You won’t be asked to do something, and you won’t be told to do it either,’ they were informed. ‘You’ll be ordered, and you’d better know the difference.’

Among the many topics covered in the lectures was the uncomfortable subject of venereal disease, or ‘VD’. Many girls who had yet to learn the facts of life were shocked at being told about the virtues of ‘French letters’, and even the more worldly wise were horrified by the grisly photographs of syphilitic sores that flashed up on a giant screen in front of them. But for the ATS, sexually transmitted diseases were no laughing matter. National rates of gonorrhoea and syphilis had more than doubled since the start of the war, and it was estimated that one out of every 200 ATS girls had already been infected.

Of all the lectures that Jessie attended in her first week of training, the one that made the strongest impression on her was a talk about Anti-Aircraft Command. To begin with, the Royal Artillery’s ‘ack-ack’ gun-sites had been strictly male environments, but the drive to free up men for fighting roles abroad was seeing the formation of a number of mixed heavy gun batteries. The prime minister’s daughter, Mary Churchill, had been among the earliest ATS girls to join one of them.

The Army was keen to boost recruitment among the current cohort of ATS trainees, and as the girls sat and listened, the speakers pressed home the importance of the guns in defending Britain’s cities against German bombers. ‘When you’re asked what job you’d like to do in the Army,’ they told the hut full of young women, ‘we want as many of you as possible to request ack-ack.’

Jessie was very much taken with the idea of serving on the guns. She had joined the ATS keen to do something meaningful for the war effort, and helping to shoot down German planes sounded a lot more exciting than answering the telephone or working as a kitchen orderly like her old schoolmate Peggy. And the idea that, like Jim, she would be serving in the Royal Artillery appealed to her too. She decided then and there that when the time came, she would put her name down for ack-ack.

After a week of daily drill, even the most uncoordinated recruits had begun to master the basics of marching, and were able to about-turn at a moment’s notice, salute to the side while still moving forwards, and halt without piling into each other. Now that she wasn’t the only girl capable of keeping in rhythm, Jessie was enjoying the regular practices more than ever. She might be petite, but she felt like a small cog in a very powerful machine, and the sound of a hundred feet hitting the ground together was exhilarating.

Jessie was also growing used to the regimented nature of Army life, which infused every hour of her time at the training camp. In the mornings the girls had to dismantle – or ‘barrack’ – their bedclothes, stacking them up in perfect piles. Then they were subjected to kit inspections, in which each item had to be laid out in a prescribed pattern. At night, they had to polish their shoes and tunic buttons until they shone.

Every moment of the day was accounted for – the girls were told when to wake up and when to go to sleep, even when to visit the communal washing facilities, or ‘ablutions’, where they were allowed to shower three times a week. The lack of privacy there was just part of the ATS way of life – a reminder that, like every item of kit, the girls’ bodies belonged to the Army.

The one small touch of individuality they were allowed was a little shelf above each bed, where they could place a few personal items. Jessie had proudly displayed a photograph of Jim, and she saw that many of the other girls also had pictures of their sweethearts back home.

Despite the busy training schedule, Jessie wrote to her fiancé every couple of days, but she was kept so busy that she barely had time to miss him. In the evenings the girls in her hut would stay up singing and chatting together until lights out at 10.30 p.m., and if they weren’t cleaning and polishing their uniforms while they did it, they were doing embroidery. There was a concession in the barracks that sold the patterns, and Jessie was working on a tablecloth.

If the first part of ATS training was about instilling a respect for Army discipline, the second was for sorting the wheat from the chaff. The girls lined up in an exam hall to sit a series of intelligence and aptitude tests, with questions on general reasoning and mathematics. There they were asked to write an essay about their lives before they had signed up, to assess their spelling and grammar.

When the written exams were out of the way, they were given eye checks to establish how far they could see, and a steady-hand test where they had to avoid setting off a buzzer. Then there were memory and visual recognition tests, in which cards showing various German planes were flashed in front of them and they had to try to remember which was which.

By the time Jessie was led into a little room and asked what trade she would like to be considered for, her head was spinning, but she confidently proclaimed, ‘Ack-ack, please.’ A corporal made a note on a clipboard and sent her on her way.

Finally, at the end of their time at the training camp, the girls all gathered to be assigned to their postings. As a corporal read their names off a list one by one, they waited anxiously to hear what their future in the Army would be. Some trades, such as cook, were so unpopular that girls had been known to go to extreme lengths to get out of them, as evidenced by the occasional dollop of mustard in the morning’s porridge.

Since Jessie’s surname was Ward, she was one of the last to hear what role she had been assigned to. Mary and Olive had already been told they were going to an ack-ack training camp in Berkshire, and she crossed her fingers, hoping that she would be setting off with them.

Finally, the corporal came to her name. ‘Private Ward,’ she called out. ‘Anti-aircraft.’

At that moment, Jessie couldn’t have been happier. She was joining the artillery, and would soon be giving the Germans what for.