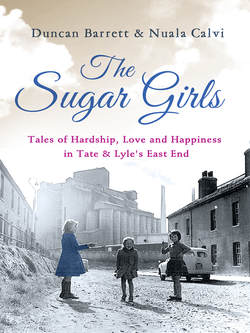

Читать книгу The Sugar Girls: Tales of Hardship, Love and Happiness in Tate & Lyle’s East End - Duncan Barrett - Страница 9

Lilian

ОглавлениеWhen Lilian Tull came to Tate & Lyle shortly after the end of the war, she was older than most new arrivals. A lanky, fair-haired woman of 23, she worked in the can-making department, where the Golden Syrup tins were assembled. Lilian had arrived on the job with a heavy heart, and her colleagues noticed a sad, far-away look in her eyes. At break times she could often be seen gazing at a small photograph that she kept in the pocket of her dungarees.

Lilian’s job was to check that the bottoms of the syrup tins were properly sealed. She would pick up five at a time using a long fork and then suction test each one on a special disc. The ones that were faulty fell off and were sent for resealing, while the others continued on their way to the syrup-filling department.

The can-making suited Lilian, because the machines were so noisy it was difficult to talk. Many of the girls had developed the ability to lip-read, but even so the forelady, Rosie Hale, kept an eye out for anyone who seemed to be neglecting their machines, patrolling the room on a balcony above the girls and shouting ‘No talking! Back to work!’ She never had need to scold Lilian, who lacked the high spirits of her chirpy colleagues.

From her earliest years life had been a struggle for Lilian, and she knew the bitter taste of poverty well, having grown up in the dark days of the Great Depression. The Tull family had all slept in a single room on the ground floor of 19 Conway Street, Plaistow. The children shared a bed with their parents, which became increasingly crowded since their mother Edith seemed always to be pregnant or nursing a newborn. Nine babies came along altogether, and were kept quiet with dummies made from rags stuffed with bread and dipped in Tate & Lyle sugar.

The children were clothed in handouts from the church, chopped down to child-size proportions and re-hemmed by their mother. Their father’s Sunday suit was a hand-me-down from the Pearces across the road – the only family in the street rich enough to afford a Christmas tree, and therefore considered ‘posh’. Whenever he wore the suit, Harry Tull was painfully aware that all the neighbours recognised it from its previous owner.

Harry did shift work at the ICI sodaworks in Silvertown, coming home each night covered in cuts from the sharp pieces of soda he chopped up all day. Lilian’s mother Edith would tenderly dress his wounds with strips of cloth covered in Melrose ointment. Keeping a large family on his wages wasn’t easy, and life was lived constantly ‘on the book’, with this week’s money going to pay off last week’s shopping bill at Weaver’s, the shop on the corner. The children were sent down to the greengrocers each weekend to ask for a ha’pence of specks – bad apples – to supplement their diet, and happily gorged on the bits of fruit that were left over once the rotten parts had been cut out.

Despite their poverty, Edith Tull was extremely house-proud. Every morning she could be seen on her hands and knees, scrubbing and whitening the doorstep until it glowed. Next, the shared toilet in the back yard was swilled down with hot water and new squares of newspaper were threaded onto the rusty nail that served as a loo-paper dispenser. Then the coconut matting came up and the place was swept and dusted vigorously until lunchtime. Monday was wash day, when Edith would rub the family’s dirty linen on her washboard until her arms were covered in angry red blisters. Friday was the day for baths, with water heated in the copper by burning old shoes and boots if there was no money for fuel.

Before her husband returned from work each evening, Edith got a fresh piece of newspaper for a tablecloth and carefully laid out the mismatched cutlery and crockery she had got from the rag-and-bone man. Harry would come home and nod in approval. A strict, Victorian-style father, he regarded family teatime as sacred, and tapped his children with his knife if they weren’t sitting up straight. The children themselves were too scared to speak at the table for fear of their father’s disapproval, so mealtimes generally passed in silence. Secretly, they all looked forward to the weeks when he was on the late shift and their more soft-hearted mother allowed them to stay up past their bedtime.

Death seemed to hover over the Tull household. Baby boys Bernard and George came into the world and departed it the same day. When Lilian was six, her grandfather passed away suddenly, and not long afterwards her three-year-old brother Charlie died from unknown causes.

The latest death shook the normally restrained Harry Tull to the core. ‘There’s a curse on this family,’ he cried bitterly.

Harry’s greatest shame was that, since there was no money for a private burial, Charlie would have to be laid to rest in a communal grave at West Ham Cemetery, without a headstone. ‘No son of mine’s going to be buried in an unmarked grave,’ he said, storming out to the back yard.

Lilian went to follow him, but Edith put a hand on her shoulder. ‘Leave him be, love,’ she said. ‘Leave him be.’

Several hours later, Harry was still outside. ‘What’s Daddy doing?’ Lilian asked her mother.

‘Don’t you worry about that,’ came the reply.

Finally, Harry came back into the house, a look of silent suffering on his face. In his hand was a wooden cross he had made himself, the words ‘RIP CHARLIE’ lovingly carved into it.

‘It’s beautiful, Harry,’ Edith said. Lilian saw that her eyes were filling with tears, and felt her own well up, too.

As was the custom, Charlie was laid out in his little coffin in the front room, for family and neighbours to pay their respects. Lilian watched the people come and go, wondering who they all were and why they wanted to stare at her brother.

As night fell the visitors no longer came and Edith told the children it was time for bed. ‘What about Charlie?’ Lilian asked.

There was nowhere else to put him, so the family bedded down in the same room as the coffin. ‘Don’t worry, love, he’ll be sleeping too,’ Lilian’s mother reassured her, gently stroking her blonde hair.

Lilian lay awake all night, thinking about her dead brother lying just feet away from her and wondering if he was going to wake up in the morning.

When Charlie was buried the whole family laid flowers on the grave and Harry hammered the little cross into the earth. Out in the open it looked smaller and more delicate than it had in the house, flimsy in comparison with the real headstones elsewhere in the cemetery.

Harry shook his head. ‘It ain’t right,’ he muttered to Edith.

When they got back to Conway Street, Harry sat with his head in his hands for a long time. Then, suddenly, he got up and marched over to the family’s rickety old marble-topped washstand – virtually the only piece of furniture in the otherwise barren room – and began dismantling it.

‘Harry – what on earth are you doing?’ Edith cried, rushing over to him.

‘If I can’t afford to buy a headstone, then I’ll just have to give this to Charlie,’ he said, yanking the marble away from the wood.

Edith and the children watched open-mouthed as their father heaved the large slab under his arm and walked out of the door.

That Sunday, the children went with their parents to lay flowers at the cemetery. Lilian looked for the little wooden cross but couldn’t find it. ‘Where’s Charlie’s cross gone?’ she asked her mother anxiously.

‘Charlie doesn’t need it any more, sweetheart,’ Edith told her. ‘Look.’

There in the earth was a marble heart, carved out of the washstand, with the name ‘CHARLIE’ engraved upon it.

When Lilian was 12 the Tulls were rehoused in a block of flats near West Ham station. The local fruit and veg seller lent them his horse and cart, and Harry and Edith piled into it what few possessions they had, followed by their children. ‘I’m not sorry to see the back of that place,’ said Edith, as they set off.

The Tulls couldn’t believe their luck when they saw their new home. There were three bedrooms, which meant that Harry and Edith could sleep alone for the first time in more than a decade, and the boys and girls now had separate rooms, even if they did still have to share beds. ‘Look, Harry!’ said Edith in delight. ‘There’s a bathroom!’

Edith’s enthusiasm for vertical living quickly waned, however. Their flat was on the top floor, and with no lifts in the building, climbing the stairs loaded with her shopping from Rathbone Market in Canning Town left her utterly exhausted. She had never been a robust woman, but now she had less energy than ever.

For Lilian, a shy, awkward child, the move to the flats brought her first true friend – a girl by the name of Lily Middleditch. The two soon became thick as thieves.

As the children grew older, Harry consoled himself over the loss of three sons by putting all his hopes into his eldest child, Harry Jnr, who was proving to be something of a brainbox at school. When he passed his exams, his father, glowing with pride, took Harry Jnr to work with him and got him a job in the offices at ICI. He himself might still be chopping soda, but now he went to work with his head held high, knowing his son was working ‘upstairs’.

Lilian, meanwhile, was increasingly feeling like the school dunce. She was persistently coming bottom of the class and becoming shyer and shyer as a result. When she left school at 14, she and Lily Middleditch got themselves jobs at the RC Mills bakery in Hermit Road. For Lilian the bakery was a haven, where, unlike at school, she found something she enjoyed and that didn’t make her feel stupid. She loved to help the baker make his fairy cakes and breathe in the sweet smells seeping from the ovens as they rose. The fresh ones went to the shop at the front, but the stale ones Lilian collected to sell off at the back door for a penny each to the long queues of hungry people who waited there each day.

Lilian was accident prone, however, and one day she burned her hand badly. ‘Someone take that girl to the hospital,’ shouted the baker, horrified, and Lily Middleditch quickly ran over, wrapped the wound in a tea towel and led Lilian away. The accident scarred her for life, but she refused to give up her job in the bakery.

Lilian was 16 when war broke out, and when the Blitz began a year later her mother and the younger children were evacuated to Oxfordshire. Since Lilian and Harry Jnr were in work and the family needed the money, they stayed in London with their father. Her brother had tried to volunteer for the Air Force but had failed the medical on account of an irregular heartbeat.

One Saturday, Lilian and Lily Middleditch had planned a trip to Green Street to look around the market. They worked the morning in the bakery as usual, then dusted the flour off their clothes and headed to West Ham station, arm in arm, to get the train.

The girls entered the station, bought their tickets and went up the stairs to the platform. As they waited for the train, they chatted excitedly about what they were going to buy. After a few minutes, they heard the mournful whine of an air-raid siren. ‘Oh God,’ said Lily Middleditch. ‘It had to be on our afternoon off, didn’t it?’

‘Lily, look,’ said Lilian, in a shaky voice, her eyes fixed on the sky over her head. Lily followed her gaze. There in the near distance was a line of tiny black planes, growing closer by the second. Lilian could already hear the distant grind of the engines, pulsing insistently. It was clear there was no time to get to a shelter and the station wasn’t underground. She felt a sickening dread wash over her.

People began running along the platform towards the exit. Lily set off, but Lilian was still rooted to the spot, staring at the planes as if mesmerised by them.

Lily ran back and yanked at her arm. ‘What are you doing? Come on!’ she yelled, pulling Lilian behind her.

They made it to the top of the stairs and had just begun to hurry down them when they heard the first bombs drop. People started to panic, missing their footing and stumbling as they ran down the steps. A little girl screamed in her mother’s arms. At the bottom a knot of confused people bumped into each other. ‘Where do we go? Where do we go?’ they asked frantically.

‘Get down, everyone,’ a man shouted. All around him the crowd obediently dropped to the floor. Lilian and Lily lay as flat as they could, their hands over their heads. No one said a word. They heard another explosion, then another. Lilian was shaking, and Lily reached out and held her hand, squeezing it hard.

Just then there was an almighty blast and a terrible crashing sound. The whole station seemed to shake and a hot wind rushed over Lilian’s body, almost blowing her over. It was followed by the sensation of something soft raining down on her head and back. Lilian realised she had been holding her breath and now desperately needed to breathe, but as she gasped she seemed to be drawing not air into her lungs but thick, bitter powder, causing her to splutter and retch.

Beside her she could hear coughing, which soon gave way to screams. There was a horrible crunching sound and she could feel something heavier now dropping onto her back, as if she was being pelted with pebbles.

This is it, she thought, the station’s collapsing. I’m going to die.

Lilian tried to tuck her head even closer into her body, protecting her neck from the onslaught as well. She had lost Lily’s hand but didn’t dare reach out for it again. After a while she couldn’t feel the debris hitting her body directly any more, but the mass on top of her grew heavier and heavier. Her mouth was on the arm of her cardigan and she tried to suck air through it to avoid breathing in more dust. Time seemed to stand still, and in her mind Lilian could see her parents’ faces, dropping in despair as they were told they had lost another child, while behind them someone cried ‘Lilian … Lilian … Lilian.’

Suddenly the faces disappeared and the sound of her name being called rushed to the fore. It wasn’t in her head now but above her, and it was accompanied by a raking sound. She felt hands reaching through the debris and encircling her upper body, and she was lifted out of the rubble, dust and stones streaming off her. Lily Middleditch was there, and Lilian realised it was her voice she had heard. She grabbed her friend’s hand and they followed the other people, stumbling and gasping, out into the sunlight.

Although she was outside, Lilian found it was still impossible to breathe through her nose because her nostrils were completely blocked with dirt and dust. It was in her ears too, and in her eyes, which were itchy and sore. Her fair hair was coated in grey, and everyone’s faces and clothes were grey too, as if the colour had been drained out of them.

She and Lily hugged each other and then without a word began to run down Manor Road back towards her block of flats. All around lay the wreckage of other buildings destroyed in the raid, and dirty, bloodied people were everywhere, some of them desperately pulling at piles of bricks, others simply standing around in shock. But Lilian didn’t have time to think about anyone else. All she wanted to know was whether her brother and father – who would have finished his Saturday shift around the same time as her – were all right.

As they turned the corner, Lilian’s heart sank. The block of flats had been hit and her mother’s beloved apartment, with its bathroom and separate bedrooms, had been blown to smithereens.

Panic-stricken, she ran towards the remains of the building shouting, ‘Dad! Harry!’ Her throat was so dry from breathing in the dust that it came out as a rasping noise.

She had lost Lily Middleditch in the chaos but as she scoured the scene her eyes landed on a familiar face – that of their neighbour, Mrs Draycock. Seeing Lilian distressed and dirty she hurried over.

‘Lil, don’t worry, there was nobody in,’ she said. ‘You all right?’

‘Yes, I’m – all covered in dust,’ Lilian blurted out. For the first time, she realised she was shaking.

Mrs Draycock put her arm around her. ‘Never mind about that now, love. You come with us – we’re going to the country to get away from all of this.’

Lilian could do nothing but nod mutely. She followed Mrs Draycock, her daughter Rosie and son Bobby, and boarded a bus heading out to Essex.

A short time later, they arrived at the village of Dunmow and were assigned a condemned cottage to stay in. Lilian was still covered in dust and had nothing to change into, but the local church was handing out old clothes and she gratefully took a bundle. When she unfolded it later back at the cottage, out fell the most beautiful thing she had ever seen: a man’s dressing gown in hand-embroidered satin. She had never owned a dressing gown before.

While Lilian was safe in Dunmow, her father and Harry Jnr had returned to the flats to find them destroyed, and no sign of Lilian anywhere. They went all round the area asking those neighbours and friends who were still left there, but nobody had seen her.

Over the next few days, Harry Tull switched his search for a living, breathing daughter to one for her remains, fearing that the family curse had struck again. He went to the nearest mortuary, where he was told the corpse of a young blonde woman had been brought in and, convinced that it must be Lilian, asked to see it. He watched, trembling, as the body was uncovered – but to his relief it wasn’t her.

He went to another mortuary, and then another, always filled with a sickening certainty that this time he would find his daughter. Each time, he would breathe a sigh of relief when he discovered she wasn’t there, before the creeping dread set in again and he continued his search.

After a week, Mrs Draycock thought it safe to send her son, Bobby, back to London to let Lilian’s family know where she was. He returned the same day with Lilian’s father, who clasped his daughter so tightly in his arms that she could hardly breathe.

Then he straightened himself up and assumed his usual, Victorian manner. ‘You’re going to Oxfordshire to be with your mum from now on,’ he said, briskly. ‘You’ll be safer there.’ Mr Tull was right that his daughters were safe from the bombs in the countryside, but little did he know what other perils lay in wait for them there.

Without their father’s strict discipline and sobering presence, the younger Tulls and their mother were having the time of their lives. They were one of two evacuee families put up in the gamekeeper’s cottage on the estate of Kirtlington Park, a grand country house a few miles north of Oxford with 50 acres of parks and gardens designed by Capability Brown. An area of the park that was normally a polo ground had been cultivated by the Dig for Victory campaign, while a farm had been turned into an RAF airfield. Hundreds of evacuees and land girls were living in the great house itself.

Coming from the bombed-out East End, Lilian thought her new home was a paradise, and without her father around she felt freer than she had for a long time. One of the first notable effects of this new freedom was the possibility of fraternising with the opposite sex.

At home, Lilian’s father had kept a close watch over his daughters, making it nigh on impossible for boys to get anywhere near them. A few months earlier, Lilian and Lily Middleditch had met some boys at Memorial Avenue Park, and as they were walking back towards the flats one of the boys, who had taken a shine to Lilian, flirtatiously pulled the scarf she was wearing off her neck. Up on the top floor, Harry Tull was leaning out of the window, intently watching the proceedings through a sixpenny toy telescope belonging to his youngest son, Leslie. As soon as he saw the scarf slipping from his daughter’s neck his head popped back into the house, the telescope dropped to the floor and he rushed as fast as he could down the stairs and out of the flats. He marched up to the group of terrified teenagers, clamped his hand on Lilian’s shoulder and commanded: ‘Home!’

In Oxfordshire, far away from the long arm of Harry Tull, Lilian and her sister Edie – who was just a year her junior – were brave enough to venture into the village alone in the evenings. There they attended the Kirtlington village hall, which was becoming quite a hub for dances at the time, what with all the land girls looking for some distraction in the countryside. Unfortunately there were never enough men to go around, which left many of the girls standing at the side of the room or resorting to dancing with each other for most of the evening. Lilian didn’t mind – her natural shyness meant she was happy just watching the spectacle.

One night, however, as the band was striking up a waltz, she saw a handsome, dark-haired young man walking across the room towards her. Instinctively, Lilian glanced over her shoulder to see who he was looking for, but Edie and all the girls behind her had moved away to get drinks.

‘Would you like to dance?’ he asked, holding out his hand. Lilian was gobsmacked. He sounded so gentlemanly and grown-up, and must be at least ten years her senior. Why on earth would he want to dance with a lanky teenager like her?

She gave him a shy smile. ‘I don’t know how to waltz,’ she said.

‘Never mind, just follow me,’ he replied, taking her hand and leading her onto the dance floor.

To begin with, Lilian tried awkwardly to follow his steps, but her limbs were rigid. ‘Just relax,’ the man whispered gently. Suddenly the two of them seemed to be in perfect unison, and she was twirling across the floor as if she did this every night. Lilian caught sight of Edie at the side of the room, staring at her with a look of surprise and disbelief. She quickly closed her eyes before her sister’s expression ruined her composure.

With her eyes closed, Lilian could focus completely on the sensation of being held by another human being. It wasn’t one she was used to, and it felt so safe and secure.

Over time, Lilian learned that the handsome stranger’s name was Reggie, that he was 27, and that he had been born and brought up in Kirtlington. He worked at the Morris Motor Company factory in Cowley, near Oxford, which to his delight was now producing mine sinkers and Tiger Moths instead of cars.

Suddenly Lilian’s life was full of music, dancing and laughter. She and Reggie went dancing in the village hall every Friday and Saturday, and for long country walks together on Sundays. Reggie always escorted her home to the gamekeeper’s house on the outskirts of the village, and with no Harry Tull around they smooched on the doorstep for as long as they liked.

‘He’s such a lovely-looking fella,’ swooned Lilian’s mother Edith. ‘Such nice manners, too.’

‘It’s not fair,’ complained Lilian’s sister Edie. ‘Why can’t I meet someone like Reggie?’

‘We’ll find you a nice man soon enough, don’t you worry, my girl,’ said her mother.

Edith’s promise was fulfilled sooner than she expected. A few days later, she returned from shopping in the village to see a lorry parked at the side of the road and a young soldier standing next to it.

Wandering over to see if he was all right, she discovered that the young man’s vehicle had broken down and he was waiting for assistance, but it was likely to be a while coming. He was shy and sweet-looking, and Edith took to him instantly. ‘Come inside for a cuppa, why don’t you?’ she said, smiling to herself, and he happily followed her into the gamekeeper’s house.

‘Edie,’ she called, as she came in, ‘there’s a young soldier here’s broken down and wants a cup of tea.’

Edie came rushing to the door, smiling her most winsome smile, and the man looked at her as if he had just walked through the gates of heaven.

Harry, as he was called, was a farm labourer from Suffolk who was down in Oxfordshire with the Army on manoeuvres, and soon he and Edie were a couple of lovebirds like Lilian and Reggie. Their mother looked on in pleasure at her two daughters and their handsome young men.

‘We’re Edith and Harry, just like you and Dad!’ Edie told her. ‘Ain’t it perfect?’

‘What would Dad do if he could see us now?’ Lilian chipped in.

The question hung in the air and she and Edie both shuddered slightly. Then they burst out laughing.

The country idyll ended all too soon for Lilian when she was called up for war work and assigned a job at the Plessey electronics factory in Ilford, which was now producing shell cases and aircraft components. Her Aunty Hilda, her father’s sister, had found the family a new house in Cranley Road, Plaistow, and Lilian was to move back in with her father and brother. She was devastated.

‘Reggie,’ she sobbed, ‘promise me you’ll write.’

‘Course I will,’ he said, holding her tight. ‘I’ve got a little something for you for when you’re not with me.’

He reached into his pocket and drew out a small photograph. ‘I had it taken in Oxford,’ he said, proudly.

Lilian clasped it to her breast, grateful to have something of Reggie to take with her.

Back in the East End, the days at Plessey’s were long and the work was frequently interrupted by air-raid sirens. Lilian was sad to discover that her friend Lily Middleditch had joined the forces and was no longer around. She lived only for Reggie’s letters now, rushing to the door to be the first to get her hands on the post so that her father wouldn’t see them, and squirrelling them away until she was safely on the bus out of Plaistow. She would read every letter slowly, making each word last. Every break time the latest missive would come out again and Lilian would reread it, until the creases in the paper had worn thin.

At first, Lilian was sending two letters for every one she received from Reggie. Then it became three, then four. To her desperation his correspondence was petering out. She wrote to him again, begging him to reply, and his letters became more frequent. Lilian’s heart soared. But it was short-lived, and soon the letters were thinning out once more.

At work, Lilian found it hard to concentrate and before long her clumsiness got the better of her again. A piece of machinery came down on her finger, leaving a scar.

‘What’s wrong with you, girl?’ asked her forelady.

‘I’m sorry,’ she cried. ‘I just wasn’t quick enough.’

To avoid the long evenings at home with her father, and to take her mind off Reggie, Lilian volunteered as an air-raid warden. Every night she donned her blue uniform and set out on the lookout for fires. But no matter how many flames she doused, her love for Reggie burned all the stronger.

When her mother and siblings returned to London, however, she discovered she wasn’t the only one with problems stemming from those carefree country days.

Lilian was walking along Cranley Road on her way home from work when she heard the unprecedented sound of shouting coming from her house. Nervously, she pushed open the front door, slipped inside and closed it quickly behind her.

Her father was in a rage the like of which she had never seen before. ‘It’s a disgrace,’ he was shouting, ‘a disgrace to the whole family!’ Before him stood her mother and, sobbing in her arms, a distraught Edie. As Lilian entered the room, Harry Tull stormed out of it, and Edie collapsed to the floor.

‘Edie, what’s happened?’ asked Lilian, rushing over to her, but Edie was too upset to speak.

‘She’s pregnant, love,’ said her mother, quietly. Lilian looked down at her sister’s shaking body. ‘I should have done something,’ Edith continued, miserably. ‘I should have done something.’

‘No, Mum,’ said Edie, suddenly looking up, her face wet and patchy with redness. ‘It’s not your fault.’ Then she looked at Lilian. ‘Oh Lil,’ she said, ‘what am I going to do?’

‘We’ll just have to write to Harry and get you two wed,’ said her mother, hopefully. ‘It’ll all work out fine, just you see.’

If Harry had been close at hand, no doubt Edie’s father would have marched him to the altar immediately, but he was far away, fighting abroad. The agonising wait for letters to be sent and received ensued, and when the response finally came it was worse than they could have feared. Harry, it turned out, was already married.

The girls’ upstanding, Victorian father was facing the unthinkable: an unmarried daughter giving birth to a child under his roof, with no hope of being made an honest woman. The disgrace to the family was beyond measure. How would Harry Tull cope with the shame? Would he disown Edie? His wife knew she had to do something fast.

‘I’ve found out about a lovely little place run by the Salvation Army,’ she told Edie a few days later. ‘It’s in Hackney, up in North London, so no one from round here will know where you are.’

Edie nodded silently. She knew there was no point in protesting. Lilian said goodbye to her sister, and for the next few months Edie disappeared from their lives, seen only by their mother in discreet visits.

In the autumn of that year, Edie returned, looking older and more womanly than Lilian remembered. In her arms was a little baby boy. ‘I named him Brian,’ she said. ‘Brian Tull.’

Her father looked down at the sleepy face of the baby, not so unlike little Charlie who had been lost before the war, and his heart melted.

Before long Harry Tull was out in the yard once again, this time whistling away as he built a cot for Brian out of some scraps of wood. He duly proved himself the most doting grandfather in the East End.

Meanwhile his daughter Edie lived in hope that once her Harry came out of the Army he would return to her and meet the son he had fathered.

By the time Lilian joined Tate & Lyle, soon after the war was over, Reggie’s letters to her had stopped completely. Yet something about him, about the way he had made her feel when she danced in his arms, meant she just couldn’t let him go, and she felt that she never would.

Lilian kept the little black-and-white photograph he had given her when she left Kirtlington, and when she thought no one was looking she would take it out and look at it longingly. She read his last letter over and over again, trying to decipher the meaning behind the words. Had he met someone else? Had she done something wrong? The questions hanging over the end of their affair tortured her constantly.

Meanwhile her best friend, Lily Middleditch, wrote to say she had met and married a soldier while in the forces and would be moving to his home town of Blackpool. Lilian had never felt more alone.

At the factory, Lilian found she wasn’t the only one whose mind kept drifting back to the events of the war years. In her department, a girl called Winnie Taylor told of her friend Olive, who had been buried in the rubble when the shop she worked in was hit by a doodlebug. She escaped with her life but was deeply traumatised, unable to cope with any sudden noises, and thereafter always had a stammer. Many Tate & Lyle workers found it hard to escape their memories, particularly the scenes of violence and bloodshed they had witnessed. On the Hesser Floor, Anne Purcell couldn’t shake the image of a neighbour she had found lying on the ground after a bombing raid, her arteries and veins hanging out of her arm; in the Print Room, Pat Johnston was haunted by the memory of a bus conductress she saw running up her road with one eye blown out. Meanwhile, Pat’s teenage cousin was losing his hair from the stress of witnessing a woman’s head being blown off by a bomb, seconds after she had pushed him out of harm’s way.

In the factory offices, a girl called Barbara Bailey still bore the scars she had suffered when a window had blown in during a bombing raid and filled her face with glass. Her mother had told her to get under the kitchen table, but Barbara was reading a book at the time and had insisted on getting to the end of the page.

The men of the factory had their own traumatic memories to deal with. Some had been interned in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps and now struggled when they saw oriental boats on the Thames – whenever one passed the raw sugar landing, the men there shouted for ‘the bastards’ to be thrown overboard. Others had been involved in the liberation of Belsen, and told stories of the terrible scenes they had witnessed.

Many refugees had settled in the East End after the war, and among them, at Tate & Lyle, was a Polish man called Bassie. His steel-grey eyes always seemed to be staring at unknown horrors, but nobody dared ask what they were.

One bitterly cold day it was snowing, and Bassie was pulling the handle of a truck carrying bags of sugar on steel pallets. Two younger men were meant to be helping, but were slacking off and complaining about the cold.

‘You think this is cold?’ Bassie demanded suddenly.

‘Yeah, Bassie, it is,’ they replied.

‘You don’t know cold,’ he said. ‘You don’t know hard. I’ve chopped trees at 50 below zero in Siberia. When the Russians invaded our country they took us away in cattle trucks and gave us rotten fish eggs and old bones to eat. They made us dig holes to live in. If you couldn’t do it, kneel down and bang, you’re dead.’

The boys were shocked by Bassie’s words, but fascinated to hear the normally reticent man speak about his past, and were determined to question him further. They learned that he had come to Britain under an arrangement to take Polish prisoners into the forces.

‘Why didn’t you go back to Poland after the war?’ asked one of the young men, Erik Gregory.

‘I can’t go home,’ Bassie replied. ‘There is nothing there.’

‘What about your family?’ Erik asked him.

Bassie shook his head. ‘Auschwitz,’ he said quietly. ‘Gassed by the Germans. You don’t know what hardship is, and I never want you to. But don’t you take the piss with me.’

The boys nodded respectfully, and never complained to Bassie about their work again.