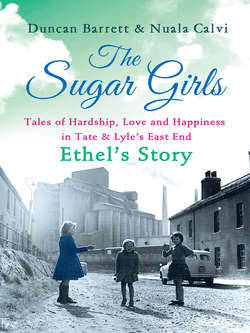

Читать книгу The Sugar Girls – Ethel’s Story: Tales of Hardship, Love and Happiness in Tate & Lyle’s East End - Duncan Barrett - Страница 8

1

ОглавлениеOn a crisp September day in 1944, Ethel Alleyne stood outside Tate & Lyle’s Plaistow Wharf refinery, looking up at the giant gate with its elaborate wrought iron and shining white clock.

A wiry, frizzy-haired girl with light-brown skin and keen dark eyes, she was wearing her best dress for the occasion – black with red trimmings. In one hand she clutched her headmaster’s testimonial, already proudly committed to memory:

Ethel’s attendance has been regular and punctual. She is a very willing, cheerful girl, always ready to give her best. Her neatness and tidiness and general attention to detail are very pleasing. I can recommend her to any employer as a conscientious worker.

At 14, Ethel had never been inside a factory, but she felt as if she’d been preparing for this moment all her life. She had grown up in the heart of Silvertown and was used to living in the shadow of the Sugar Mile – the stretch of colossal factories that ran between Tate & Lyle’s sugar and syrup refineries. The factory life was in her blood – her mother’s family had lived in the area for generations, working in Keiller’s jam and marmalade factory, and her grandfather would tell anyone who would listen that he remembered when Silvertown was little more than a marsh.

From a hut on the left of the entrance emerged a fierce-looking man in the smart, military-style uniform of a commissionaire, his navy-blue tunic buttoned up to the collar and the silver buttons gleaming in the sunlight.

‘Yes, darlin’?’

Ethel drew herself up to her full height and did her best to hide her nerves. ‘I’m here about a job,’ she told him.

‘In here.’ He gestured for her to follow him into the little hut.

Inside, Ethel stood anxiously while a man in a white boiler-suit glanced over her testimonial and noted down a few details on a form. ‘Hesser Floor, I reckon,’ he told her briskly, ‘but the surgery will need to check you out first. I’ll get a girl to take you.’

Before long a smartly dressed young woman who looked to be in her late teens arrived at the door. ‘Hesser girl?’ she asked Ethel, as they stepped out of the hut.

‘Um, I think so,’ Ethel replied, ‘but I’m not sure what that means.’

‘Oh, Hesser of Stuttgart make the sugar-packing machines, but we try to keep that quiet these days! Come on.’

The two girls headed into the refinery.

Ethel was quite unprepared for the sight that met her eyes. She knew that the factory was big, but seeing it up close, from the inside, was another matter. Ahead of her, slightly to the right, the enormous grey-brick hulk of the Hesser building towered over her. At its base a team of boys and burly-looking girls were standing on a raised level open to the yard, loading up great haulage lorries with tonne-weight boards of sugar bags. To her left, another large building housed the factory’s bar and Recreation Room, and in front of her wagon tracks crisscrossed all over the ground, branching off straight ahead towards the syrup shed, where the Lyle’s Golden Syrup tins were filled. Underneath it was the Blue Room, where the sugar bags were printed, and beyond was the can-making department, where girls produced the famous tins. In the distance she could make out the looming white concrete of the pan house, where sugar liquor was boiled into crystals, and next to it an even taller set of chimneys from the boiler house.

Ethel searched in vain for the shining curve of the Thames, where the boats of raw sugar were unloaded. She knew it must be at the far end of the site, but through the jungle of warehouses in between she couldn’t catch a glimpse of the water.

As the two girls hurried across the yard, a musty, malty smell of damp sugar hit them in a cloying wave – shortly followed by another, ranker odour that almost made Ethel retch. She knew what it was, but tried her best not to think about it: the pile of rotting carcasses just the other side of the factory wall, at John Knight’s soap works. It was a smell that every Tate & Lyle worker had to learn to ignore.

In the surgery, a young nurse listened to Ethel’s heart, took her blood pressure and checked the movement and strength of her limbs. Then she carefully scoured her frizzy hair for nits, before passing her fit for service.

Ethel followed the other girl back towards the dark-grey Hesser building, on the outside of which a black metal staircase zigzagged up all eight floors. ‘It’s a long way up but you get used to it,’ said the girl, as they began to climb the steps.

As they neared the top, Ethel was beginning to lose her breath, so she was relieved to spot a sign that read: SMALL PACKETS. They went into a cloakroom, where Ethel deposited her coat and bag, and then through a pair of double doors onto the factory floor.

The noise as they stepped through the doors was overwhelming. The large room echoed with the rattle and grind of a dozen machines, huge lumps of iron around which stood teams of young women. Over the top of the noise there was music blaring out, and some of the girls were singing along.

They went up some stairs to an office on a mezzanine level, and as the door clicked shut behind them Ethel was aware of a blissful quiet settling around her. The girl left her in front of an impeccably tidy desk on which stood a little sign: IVY BATCHELOR, FORELADY. Behind the desk sat a tall, upright woman in a long white coat. Her brown hair had evidently been expertly styled, and her nails and make-up were immaculate.

‘Take a seat,’ she said calmly, gesturing to a chair on the other side of the desk.

Ethel did so, sitting up as straight as she could. She was determined to make a good impression.

The forelady looked at her kindly, reached for a form from a pile on her desk and took down Ethel’s name and address. ‘Is there any particular reason you want to work at Tate & Lyle?’ she asked.

Ethel hesitated. She had dreamed of working at one of the giant sugar factories ever since she was little and her dad had taken her to the Tate Institute, the social club opposite the Thames Refinery. They had gone to see a show laid on for local residents and employees, and Ethel had been transfixed – not merely by the dancers onstage, but by the glamorous young women who thronged the hall watching them. They were the factory’s female workforce and her dad had told her they were known as the sugar girls.

She felt self-conscious at the idea of telling that story, though. ‘I only live down the road,’ she offered instead.

Ivy Batchelor laughed gently. ‘Now, I’m afraid we can’t offer you a uniform at present, unless you have ration coupons to spare, but we should be able to lend you an apron for the day.’ She rummaged around under the desk and came up with a rather worn-looking pinny. ‘Your hours are eight to four Monday to Friday and eight to twelve on Saturday. You’re allowed half an hour for dinner and two toilet breaks a day. Any questions?’

Ethel shook her head.

‘Good. Then Mary will see you to one of the machines.’

As if on cue, a stern-looking woman with dark hair marched through the door of the office and gestured for Ethel to follow her. She was Mary Doherty, one of the department’s three supervisors, known as charge-hands.

‘This way,’ she commanded. Ethel jumped up and followed her onto the floor.

At each machine, paper bags were moving along a conveyor belt and being filled with sugar from a chute overhead. They were then sealed with a spurt of glue and a girl took them off the belt, piling them up ready to be packed. A packer then pulled down a sheet of brown paper and flipped the bags onto it in layers until they had made up a parcel, sealing it like an envelope with a bit of cold water and heaving it onto a board. When a tonne-weight of sugar had been assembled, it was taken away on a trolley down to the lorry bay. In charge of each machine was a driver, who paced around keeping an eye on everything. The girls’ various repetitive movements combined to give the impression of an elaborate ballet.

Mary led Ethel across to a machine at the far side of the room, where a woman with giant hands was parcelling up the sugar bags.

‘This is Annie Stout,’ Mary told Ethel. ‘She’ll show you how the packing is done.’ She strode off across the floor and back up to the office.

Ethel noticed that on the ends of Annie’s fat fingers were ten little paper thimbles. ‘You’ll need some of these,’ she told her, ‘or your hands’ll be bleeding by lunchtime.’

Without once interrupting her flow, Annie instructed Ethel in how to make her own thimbles from some spare scraps of paper. Then she stood back and let her have a go at packing.

At first Ethel found it hard holding several bags at once in her hands, but if she applied enough pressure to the sides, and lifted them in a clear, fluid arc, twisting them rapidly before they had a chance to slip, she found that she could manage it without dropping any.

‘That’s it,’ Annie told her approvingly. After a while, she leaned in close and Ethel thought she was going to offer to take over the job again, but instead she whispered something in her ear.

‘Got any sweetie coupons you don’t want, darlin’?’

‘Any what?’ said Ethel, taken aback by the question.

Annie whispered more emphatically: ‘Ration coupons.’

‘No, sorry,’ Ethel replied briskly. She screwed up her face as if focusing intently on her work, and tried to avoid catching Annie’s eye.

Before long Ethel’s wrists were aching from flipping layer after layer of sugar bags, and she was beginning to wonder whether it was too soon to ask for one of her two toilet breaks.

Just then there was a sudden dimming of the lights, and a voice crackled out from the loudspeakers which were stationed around the room.

‘All personnel to shelters, please. All personnel to shelters.’

The driver of Ethel’s machine swiftly pulled a lever, and the whole mechanism ground to a halt. Carefully, Ethel laid down the bags in her hands to complete a layer, and then looked up, hoping that Annie would tell her what to do next. But Annie was gone, lost in the stream of bodies filing in an orderly but hurried fashion towards the exit.

Four years after the start of the Blitz, Tate & Lyle had got evacuations down to a fine art, and could gather 1,500 of their wartime workforce into shelters within the space of four minutes. A command centre under the can-making department received signals from the national telephone exchange, and four spotters permanently stationed on the pan-house roof provided visual confirmation. Those whose jobs meant that they couldn’t simply leave their posts – such as the men on the boilers and turbines, which were not easily shut down – were provided with blast-proof shielding to keep them safe, while the rest were immediately ordered to evacuate.

Ethel rushed to join the back of the queue of sugar girls streaming out of the door. It was only now that she heard sirens outside the factory as well.

In front of her was one of the smart girls from the office. ‘You’re new, aren’t you?’ she asked.

‘Yes, it’s my first day,’ said Ethel wryly.

‘Poor you!’ the other girl replied. ‘Well, don’t worry, the shelter’s just downstairs – we can’t have them underground because of the river. I’m Joanie, by the way. Joanie Warren.’

Ethel followed Joanie back down the black iron staircase to the second floor of the building. It was the same size as the Hesser room up above, but whatever machinery it had once housed had been removed, and blast walls had been built, dividing it into compartments. The windows were all bricked up, and wooden boards lined the floor for the workers to sit on. Ethel tried hard to suppress the feeling that she was cooped up in a dungeon.

Before long, the room was packed with bodies, mostly women and girls but a fair number of men as well. By now only a third of the refinery’s employees were male, and women who had previously been forced to leave when they got married were hurriedly being recalled by an army of door-knockers. Many had taken over jobs formerly held by men – working on the lorry bank under the Hesser Floor, manning the centrifuges and working as fitters in the can-making department. Others had been assigned a variety of unusual new roles: dehydrating vegetables to be sent out in tins to the troops (often with a hopeful note containing the name and address of the girl who had sent them) and even producing aeroplane and gun parts.

A woman pushed a steaming mug of cocoa into Ethel’s hand and offered her a Matzo cracker. ‘Could be in here a while,’ Joanie advised her, ‘so you might as well have one.’

Ethel took the Matzo and they sat huddled together, straining their ears for any sound from the skies. Eventually it came: the familiar phut … phut … phut … of a doodlebug passing overhead.

When the bombs first came to Silvertown four years earlier, Ethel was living in Charles Street, a stone’s throw from the Connaught Bridge which divided the Victoria and Albert docks. The seventh of September 1940 was a balmy summer’s day, and the Alleyne family, like the rest of their neighbours in the East End, had no idea what was in store for them.

It was Ethel’s 11th birthday, and a special tea of jelly and fruit had been planned. Louise Alleyne was busy bathing her three daughters in the tin bath – first her eldest, Dolly, then Ethel and finally little Winnie. She always took great pride in making sure they were squeaky clean and smartly turned out, with spotless white socks and gleaming ruby-red shoes. Louise had high hopes for her three girls and sometimes even made them walk around the house with books on their heads to improve their posture, just as long as the neighbours weren’t looking. A strict mother, she wasn’t averse to taking her hand to her daughters if their behaviour fell short of what was expected.

Her husband, a more laid-back character, was tinkling away contentedly on the keys of a battered old upright piano. Jim Alleyne used to say that he must have acquired his musical skill from his father, a black Saint Lucian who had married a white lady and emigrated to England. When Jim was only a few years old his parents had left him and his sister Etty with a lady he knew only as Aunty Lyle, and never returned. Aunty Lyle was white, but had married a Caribbean sailor herself, and had adapted herself to the requirements of a mixed-race household, making the best rice ’n’ peas this side of the Atlantic. Jim had become a sailor like his stepfather, but when he had children he packed it in and took a job as a greaser on the Woolwich Ferry.

Jim and his two older girls often played music together, he on the piano, Dolly on guitar and Ethel on an old accordion.

He also entertained the locals at the Graving Dock Tavern on the North Woolwich Road, and at the Tate Institute. Louise could never understand how he did it, since she herself was practically tone deaf. But that didn’t stop her being an appreciative audience.

As the sirens began to sound, Jim jumped up from his stool. ‘Louise!’ he called, ‘Get those girls dressed. We’ve got to get into the shelter.’

Louise briskly dried the girls down, and passed around a set of clean clothes from the pile she had stacked neatly by her side. Then she hurried them out into the yard, where their father stood watch by the side of the brick hut that now took up most of their outdoor space.

Louise – ever the house-proud mother – had done her best to add a touch of style to the shelter, with sheets draped down the walls to keep out the damp, a little rug on the floor offering a splash of colour, and even a double bed, which barely fitted between the four cramped walls but at least meant that no one would have to spend the night on the floor.

She and the girls had just clambered onto the squeaky mattress when they heard the faint sound of planes flying overhead, followed by a series of gentle ‘crump’ sounds in the distance. Hauling the door shut behind him, Jim caught his wife’s eye for a moment as the rumbling above them grew louder.

Before long it had turned into a roar, punctuated every few moments by deep, hollow thuds of increasing ferocity. There was a sudden whoosh overhead and Jim flung himself down on top of his wife and children, spreading him arms wide to shield them from the menace above.

The noises grew louder still, and this time the sounds were more distinct: the crumbling of bricks and masonry, the jagged tinkling of shattered glass falling from windows, and, most terrifying of all, the merciless low beat of the detonating explosives, which seemed to pound the shelter walls on all sides.

With one giant blast the brick hut shook, and lifted momentarily from the ground. Then, gradually, the storm overhead began to pass, and the noises receded into the distance.

Ethel clutched her mother and sisters close as Jim sat up on the bed and looked around him. There was a trickle of bright-red blood snaking down his brown forehead. ‘Dad,’ she shouted, ‘they got you!’

Jim put a hand up to feel for the wound, smarting as he tested the cut with his finger. He let out a laugh of relief.

‘What is it, Dad?’ Ethel asked. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Don’t worry, my darlin’,’ he replied, wiping his hand on his trousers. ‘Just caught myself on the bedhead is all.’ He leaned forward so that Ethel could see he was telling the truth. ‘I’ll be more careful next time.’

Jim hugged his wife and children to him once again, tousling Dolly’s blonde locks with one hand and squeezing Ethel close with the other, while Winnie clung on to Louise for dear life. Ethel noticed that her mother had become very quiet.

At six-thirty p.m. the all-clear was sounded and the Alleyne family emerged to see what was left of their home. Half the house had been destroyed altogether, and the half that remained was in a very bad way. Windows had been blasted out of their frames, stray tiles from the roof littered the yard, and the door had been blown off its hinges.

Carefully they picked their way through the ruined building, avoiding the scattered pieces of broken crockery that should have been serving Ethel’s birthday tea, and clambering over the remains of Jim’s beloved piano, its black and white keys strewn all over the floor.

It was only once they were on the road outside that they realised how lucky they had been. Charles Street was a scene of devastation. There were piles of rubble where some houses had once stood. Others were still standing, but gaping holes revealed the pitiful sight of their inhabitants’ ruined possessions.

A grey dust was beginning to settle all around, and Ethel coughed violently as it caught in her lungs.

Jim turned and addressed the family. ‘We can’t stay here,’ he told them. ‘We’ll head for the rest centre at Woodman Street School, and I’ll come back later and pick up some clean clothes.’

Hand in hand, the family set off on the mile-long journey, passing street after street in no better state than their own. Wardens were out with stretcher-bearers, pulling injured people out of the rubble. By the side of the road were blackened bundles, some large and some small. Ethel tried to make out what they were, but her mother pulled her close, and told her not to look.

Along the docks many warehouses were ablaze, and burning butter, sugar, molasses and oils oozed out into the water and the surrounding roads, creating boiling hot puddles, thick smoke and overpowering smells.

By the time the family arrived at the rest centre, Louise Alleyne’s head was pounding and she was beginning to feel queasy. ‘I’ve got to lie down,’ she told her husband. ‘I’m getting one of my migraines.’

Jim walked with her arm in arm until they found a quiet spot where she could have a rest. ‘You stay here for a while,’ he whispered in her ear.

The main hall of the school was thronging with anxious families, most of whom looked dishevelled and miserable. Jim took one look at the scene and bounded up to the front of the hall, where an old upright piano had been pushed to the side of the stage. ‘Excuse me, mate,’ he said to a man who was leaning on it. ‘Do you mind?’

The man seemed to shake himself out of a stupor. ‘Nah, go ahead,’ he replied. ‘Bleedin’ good idea.’

As Jim sat and began tinkling away, a crowd started to gather and a throng of young women descended on the piano. Jim was used to it – his light-brown skin and musical talent had always brought him attention from the local women, and he had learned how to handle it.

‘This is my wife’s favourite song,’ he told them. ‘I reckon she thinks it was written for her.’ He began singing Maurice Chevalier’s ‘Louise’, and the women soon joined in.

Before long, other members of the crowd were singing along as well.

That night Jim played into the small hours, just happy, like the enthusiastic crowd around him, for the opportunity to clutch at something beautiful amid all the destruction and fear. Outside, the raids had started up again. By the end of the night 250 German bombers had dropped 625 tonnes of high explosive, and more than 400 lives had been lost.

The next morning Jim kept his word, and before the rest of the family had woken up he made the journey back to their bombed-out home. Officially the road had been cordoned off, but he knew that having clean clothes for the kids would mean a lot to Louise.

When Jim arrived at 23 Charles Street and carefully made his way back inside the wrecked building, he realised that his wife was going to be disappointed. What little the bombs had spared had already been looted, and drawer after drawer fell open empty. The family would have to manage with what they had on their backs.

Before long, the Alleynes were relocated to Waunlwyd, a little village near Ebbw Vale in South Wales, where Jim had accepted a job in a munitions factory. It could scarcely have been more different from the bomb-damaged East End, and for the three girls it was an adventure in an utterly unknown world.

As the train pulled into the station Ethel leapt up from her seat. ‘Look, Dad,’ she cried, barely able to believe her eyes, ‘there are sheep and geese and donkeys just walking around in the street!’

The family lived in a little house on a hill, where Louise learned to cook on a fire instead of a stove. Ethel and Dolly went to the local school, while little Winnie stayed at home with their mother.

Dolly took to the rough-and-tumble of rural life more than Ethel, who was forever trying to get the mud off her shoes. Always the more sensible sister, Ethel was frequently mistaken for the eldest by people who met the two of them. While Dolly soon made friends with a group of local Welsh children, Ethel was not admitted into their gang, who considered her too ‘miserable and boring’.

Dolly’s favourite new pastime was playing kiss-chase with the country boys, and Ethel could never understand how her sister, who was normally such a fast runner, would keep getting caught. Ethel always ran for her life, and no one ever seemed to catch up with her.

The country life proved quite a shock to Ethel, and not just because of the farm animals. One afternoon she was walking some way behind Dolly and the other children on their way to Sunday school, when a man leaped out of the bushes and exposed himself to her. She turned on the spot and ran home at full-pelt, screaming her lungs out all the way back up the hill to the house.

‘Dad! Dad!’ she exclaimed when her anxious father opened the front door, ‘there’s a man down there with a broom handle in his trousers!’

Jim Alleyne may have been a laid-back father, but when it came to protecting his girls he was fearsome. He legged it all the way down the hill in hot pursuit of the pervert, but by the time he got there both the man and his broom handle had retreated.

By 1942, although the war raged on in Europe, for Londoners the horrors of the Blitz seemed to be behind them. Like many families, the Alleynes took the decision to return to the East End. They found a house in Oriental Road, not far from Charles Street and still in the heart of Silvertown, and Jim got a job at the Spencer Chapman chemical factory. The girls’ old school had been levelled by the Luftwaffe, so they were sent to a makeshift classroom in the local swimming pool, which until recently had served as a morgue.

Ethel was thrilled to be admitted to a gang of local kids: Archie Colquhoun, Gladys Rawlins, Johnny Jay, Alf Gosford and Lenny Bridges. After being teased by Dolly and her friends for being boring, it felt wonderful to have a group of her own to lark about with at last.

Her favourite in the new gang was Archie, a ginger-haired boy a year older than her who lived on her new road, and who was as cheeky and playful as she was serious. As they ran about the streets together, playing gobstones and knock down ginger, Ethel realised that she was smitten.

There was just one unfortunate obstacle to her future happiness: Archie preferred her sister Dolly, whose tumbling blonde curls were a far cry from Ethel’s dark, frizzy hair. When he turned up at their door one afternoon asking if ‘Blondie’ would like to go for a walk, poor Ethel was horrified.

She wasn’t one to give up easily, however, and when Archie and Dolly left the house together she followed them in secret, borrowing her grandfather’s dog from across the road as an alibi in case her stalking was discovered. She did her best to stay well back, even though she was desperate to know what they were saying to each other, and kept a beady eye out for any hand-holding or kissing.

Ethel made it as far as the Connaught Bridge before her cover was blown. ‘Ooh, she’s jealous, Archie,’ Dolly called out, loudly enough to ensure that her sister could hear her. Ethel was mortified and hurried home, dragging the unfortunate dog behind her.

She decided the best strategy was to bide her time. Dolly had no shortage of male attention and would hopefully tire of Archie’s before long. Meanwhile, Ethel made sure to remind him of her presence. At 14, Archie had already left school and was working at the Hollis Bros timber yard. Every day, Ethel was out on the front step when he walked past on his way home for dinner.

Soon enough, Archie’s interest in Dolly waned, and one day he asked Ethel if she fancied going to the pictures together at the Imperial cinema in Canning Town. She tried not to jump for joy as she accepted the invitation.

Being alone with Ethel seemed to have a sobering effect on Archie, and around her he kept his cheekiness in check, behaving like the perfect gentleman. That night he didn’t dare do more than sneak an arm around her, even in the dark of the picture house.

In fact, after several months of courting, Archie still hadn’t plucked up the courage to kiss her. One day they were walking to the park together and chatting, when one of Ethel’s friends spotted them from across the road. ‘Just do it, Arch!’ she shouted. ‘Go on!’

Archie froze like a rabbit caught in the headlights, but he knew it was now or never. While Ethel was still chatting away he suddenly turned, grabbed her and planted a great big smacker on her lips.

‘Archie!’ she chastised him, as soon as their lips unlocked, ‘I was in the middle of a sentence!’

But after that she let him kiss her whenever he liked. By the time Ethel joined Tate & Lyle, she and Archie were inseparable.

Phut … phut … phut …

Ethel and Joanie held their breath, along with the hundred or so other inhabitants of the factory shelter, as they listened to the distinctive splutter of the doodlebug. They willed the noise to continue, knowing that if the engine cut out it meant the warhead was about to fall.

The flying bombs, launched from occupied Europe, had become a regular feature of East End life ever since the D-Day landings the previous summer. But at least the doodlebugs, which flew like regular aircraft, provided enough warning to get civilians into shelters. Far more menacing were the V2 rockets, which travelled so fast – at four times the speed of sound – that the explosion was the first anybody knew of them. The shock wave alone was enough to kill unsuspecting victims far from the point of impact, and in the aftermath of a V2 strike it was not uncommon to see a normal-looking bus full of passengers, apparently sitting patiently in their seats but on closer inspection all quite dead.

At the height of the V2 menace the Royal Docks were sustaining a strike every two or three days, but Tate & Lyle’s two factories escaped a single direct hit. Plaistow Wharf had suffered its fair share of battering earlier in the war, with 54 incendiary bombs landing inside the factory, all but one of which were quickly extinguished. There was only one fatality, a Mr Kinnison who ran into an exploding bomb on his way to a shelter. Downriver, the Thames Refinery was also hit many times, but only two minor casualties were reported.

Various rumours had sprung up to explain the firm’s apparent lucky streak. At the Thames Refinery, the most popular theory was that their iconic chimney – the tallest in the area – provided such a good landmark for the docks that the Luftwaffe were reluctant to damage it. At Plaistow Wharf, the story went that the mysterious Hesser company had begged Hitler not to damage their precious packing machines.

Fortunately for Ethel, Tate & Lyle’s good luck continued to hold out, and the splutter of the doodlebug finally began to recede into the distance. The inhabitants of the shelter were able to relax, and Ethel let out a sigh of relief.

Moments later the all-clear siren began to sound, and the men and women around her were suddenly getting to their feet.

‘Back to work then,’ Joanie said cheerfully, munching on the last of her cracker and brushing a few stray crumbs from her lap onto the floor. Ethel followed as they made their way back up the black iron stairs.

On the Hesser Floor, Joanie retreated up to the office, while Ethel returned to her machine, determined to perfect her packing technique. But a friendship had already been forged. Before they left work that day, the two young women had arranged to go to the pictures together.

To begin with, the rigours of her new job took their toll on Ethel. At the end of each day her hair was grey with sugar dust and her clothes were stiff with it. Every night her wrists ached painfully from the twisting movement that she had to repeat over and over again packing hundreds of sugar bags. At work, when it got really bad, she would be sent to the factory surgery, where a nurse would rub ointment on her wrists and bandage them up temporarily, before sending her straight back to the Hesser Floor. But as time went on her muscles grew accustomed to the exertions, and she found herself growing stronger and more robust.

While the work of a sugar girl was building up the muscles in Ethel’s body, her mind soon got some exercise as well. The packers had to tally up the number of sugar bags that had been packed each day and display the result on a board at the base of each machine. Ethel had always been good at maths in school and had no problem with this, but she noticed that a girl on the next machine was struggling. Before long she was doing the other girl’s tally as well as her own.

Her efforts did not go unnoticed up in the office, where the forelady Ivy Batchelor stood gazing out through the glass window over her Hesser girls. Soon she had invited Ethel up to the office to try her out on a new job, calculating the overall tonnage of the entire department. Ethel was delighted, especially since it meant working with Joanie and the other office girls. She hadn’t made any friends on the factory floor and spent most lunchtimes eating a sandwich in the cloakroom on her own while the others all went to the canteen.

Louise Alleyne could not have been more proud of her daughter’s promotion, especially since Gladys Rawlins, from Ethel’s group of friends at home, had now also joined Tate & Lyle and was not progressing beyond sweeping the floor. When Ethel informed her mother of her friend’s dead-end job, she responded in no uncertain terms, ‘They put you on a broom, you come straight home. No girl of mine’s going to sweep floors for the rest of her life.’

The words stuck in Ethel’s mind, making her all the more determined to distinguish herself at work and win her mother’s approval.

As the war moved into its final months, trips to the factory shelters grew increasingly rare. At eight p.m. on 8 May 1945 the voice of company telephonist Nellie Franks was heard over the loudspeaker system announcing that Victory in Europe had been declared. Production was shutting down immediately, and it was time to down tools and begin the party.

Most of the workers congregated in the Recreation Room, where the celebrations were soon underway, carrying on until well after midnight. Outside the factory gates, the locals had lit a huge bonfire made from railway palings and were dancing around it. Even the refinery director, Oliver Lyle, was spotted enjoying a quick jig with them on his way home.

Few parts of the country had as much reason to celebrate the end of the war as the East End, and the area lived up to its reputation for enjoying a good knees-up. Flags and bunting from the King’s coronation nine years earlier were scavenged from old cupboards and strung up all over the houses, effigies of Hitler and his generals hung from the lamp-posts, and more bonfires sprung up in the war-damaged streets, those same East Enders who had fought the blazes caused by the Luftwaffe now raiding telephone kiosks for directories to keep the fires burning. Some enthusiastic souls let off fireworks they had been storing for six years, although the explosions, however beautiful, weren’t universally popular among the battle-weary population.

While some grateful Christians hastened to church as soon as they heard the news, the majority of people hit the local pubs, where the sawdust was trampled underfoot more furiously than ever before. The amount of alcohol consumed was prodigious, and before long the drunkenness had spread to every street. Any pianos that had survived the bombing were dragged outside, along with accordions and radiograms, to provide the soundtrack to a party on a scale never seen before, and the locals sang and danced into the early hours of the morning.